The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

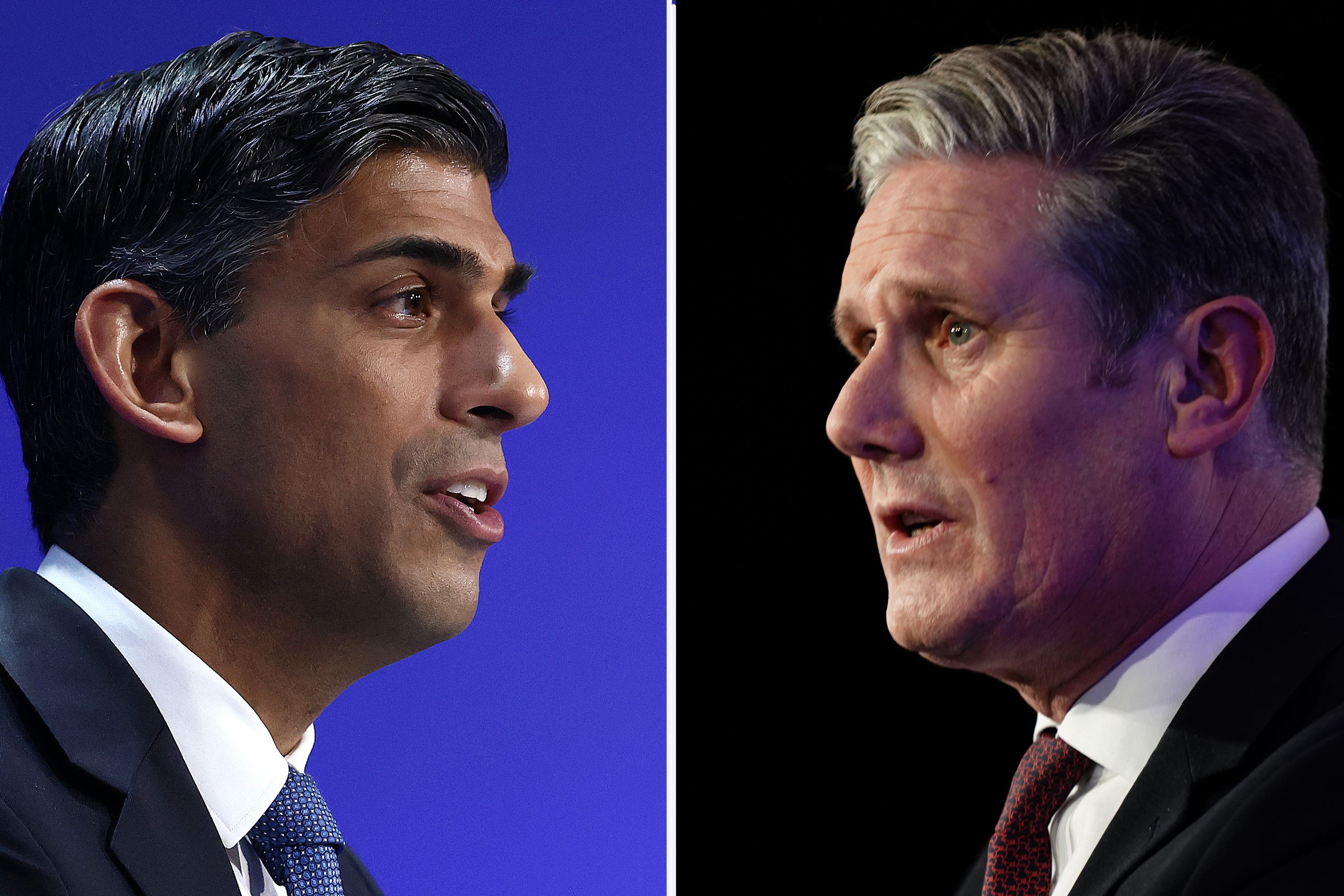

How Israel’s war could backfire – not on Sunak, but Starmer...

Normally, an international crisis poses a bigger test for the government than the opposition, writes Andrew Grice. But while the Tories are instinctively a pro-Israel party, Starmer faces a far more difficult balancing act

The war between Israel and Hamas has big implications for UK domestic politics. In his first unexpected foreign policy crisis as prime minister, Rishi Sunak has been sure-footed and statesmanlike. His Commons statement on the Middle East struck the right balance, pledging strong support for Israel’s right to defend itself after Hamas’s barbaric attack on its soil, but also acknowledged an “acute humanitarian crisis” in Gaza. Sunak plans to visit Israel, but the horrific bombing of the Al-Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza might cause him to pause.

Keir Starmer has echoed Sunak’s approach. He dashed the private hopes of Tory advisers that he might bow to the strong pro-Palestinian sentiment in his party that led some left-wingers to cross a line into antisemitism under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. Not for the first time, these Tories underestimated Starmer’s ruthless determination to avoid handing the Tories a target.

Yet this aspect of the story is not over. Starmer’s unwavering support for Israel has angered many grassroots Labour members and some MPs. During an exhausting marathon of media interviews during the Labour conference, Starmer said Israel had a right to cut off Gaza’s water and electricity.

Probably he unintentionally “oversteered” (a word he uses a lot) in order to make the attack on Israel Labour’s starting point. His deliberately tough stance on security and terrorism is designed to repair the damage Corbyn did in his hesitant response to the Salisbury poisonings, which haunted Labour at the 2019 election.

Since his initial remark, Starmer has emphasised the need for Israel to stick to international law (which his critics say rules out cutting off water supplies), said civilians in Gaza “must not be targeted”, and called for humanitarian corridors to be opened. On Tuesday, he visited NGOs operating in the Palestinian territories to discuss the humanitarian crisis.

But Starmer hasn’t retracted his initial comment and several Labour councillors have resigned from the party in protest at his approach. As a result, Labour could lose power in places including Leicester.

Starmer allies insist the big picture is that the party mood has been relatively calm, compared to what would inevitably have happened if the war had erupted during Corbyn’s leadership.

However, internal criticism of Starmer is bound to grow after the hospital bombing. Labour members who want their leader to show more sympathy for the Palestinians will not believe Israel’s denials that it was responsible, no matter what evidence it produces. Momentum, the left-wing pressure group, described Starmer’s response to the attack as “not good enough”, urged him to call out Israeli war crimes and demand a ceasefire, warning that “silence is complicity.”

A ground invasion by Israel in Gaza could burst Labour’s dam. Starmer would come under intense pressure to dial down his support for Israel and call for a ceasefire – Corbyn’s default option.

The Labour leader will not want to end the cross-party consensus on the war. But he has a very difficult balancing act. Having swept Labour’s stables clean of antisemitism, he cannot risk any sign of the stain returning. Against that, some Labour MPs will quietly remind him there are 2 million Muslim voters in Britain, many of them in Labour-held constituencies. Like Sunak, Starmer must be mindful of two very different audiences.

Starmer has been ruthless in using the Labour rulebook to dilute the influence of the left. Indeed, some left-wingers believe they will never get their hands on the party’s levers of power again. He is trying the same “command and control” approach on the Middle East; Labour councillors have been ordered by party headquarters not to join pro-Palestinian marches.

Internal disciplinary processes can be used to expel troublesome rebels and fix candidate selections but they have their limits. It’s hard to outlaw dissent on such an emotive issue as the Israel-Palestine question. In 2006, Tony Blair misjudged his party’s mood, backing Israel and president George Bush during a conflict between Israel and Lebanon and, like Starmer today, refusing to call for a ceasefire. The backlash among Labour MPs hastened Blair’s departure as prime minister, forcing him to announce he would stand down before he was ready.

Normally, an international crisis poses a bigger test for the government than the opposition. And Sunak could still be tested. He faces conflicting pressures from Tory MPs, some wanting the Iranian Revolutionary Guard proscribed as a terrorist organisation, others urging him to do more to help innocent civilians in Gaza. Street protests in the UK are bound to intensify as the war does. Though some in his party will want to extend their culture wars, Sunak will be acutely aware of his responsibility to ensure community cohesion at home.

The Tories are broadly united on the Israel-Hamas conflict; they are instinctively a pro-Israel party today. In contrast, internal voices of dissent will be much louder on the Labour side, compounding Starmer’s problem. Unusually, this crisis might just prove a bigger challenge for the leader of the opposition than the prime minister.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments