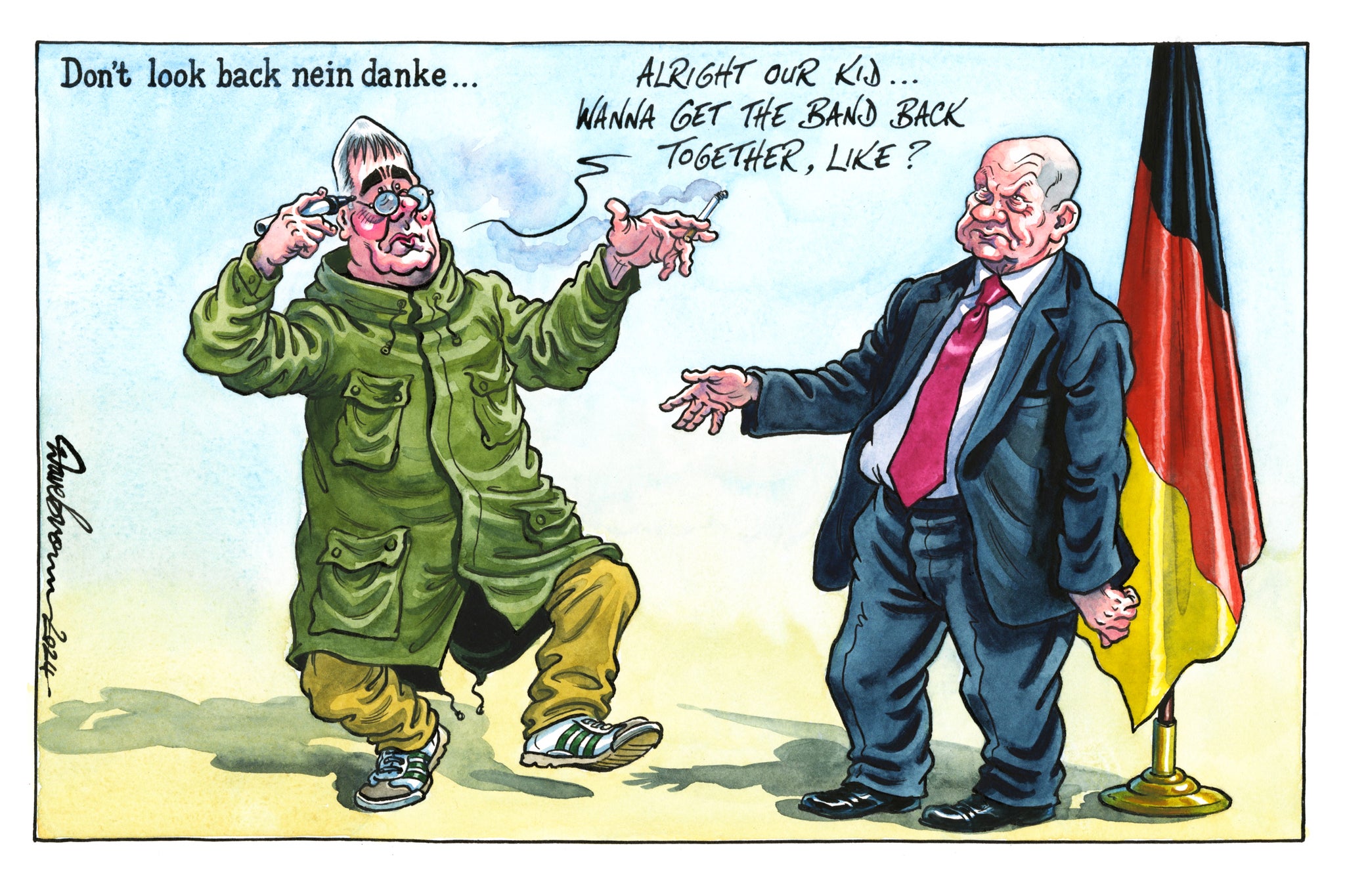

Starmer’s treaty with Germany is a moment for pro-Europeans to be optimistic

Editorial: British policy towards Europe is shifting once again towards closer integration as the gravitational pull of the UK’s largest trading partner makes itself felt once more

Even if Sir Keir Starmer’s successive visits to Berlin and Paris this week were to do no more than build a little more trust and a warmer rapport with the leaders of two of the UK’s most vital partners, then they will have done some good and will help move the UK closer to Europe – albeit not yet to its heart.

When the prime minister talks of a “reset” in post-Brexit relations, he may be fairly accused of being a touch vague about the meaning; yet it is also right to say that all such diplomatic journeys have to begin somewhere, and this one starts in a suboptimal place.

Now, after the traumas of Brexit and a period of something approaching Cold War between London and Paris, to borrow a phrase – things can only get better. It is a sphere where the state of the public finances, which constrain the government so grievously in so much of its work, need not impede some potentially historic achievements.

In fairness, the thaw began under Rishi Sunak, who concluded the Windsor Framework with the EU Commission in early 2023, and rebooted British-French relations at the Paris summit with Emmanuel Macron shortly thereafter. Never again must a British premier be as childish as Liz Truss when she said the jury is out on whether the French leader is a friend or foe of Britain, and it seems clear too that the chauvinistic buffoonery of Boris Johnson is also behind us.

Mr Sunak also developed an apparently warm friendship with the hard-right Italian prime minister Georgia Meloni – admittedly more of an ideological soulmate for the Tory leader than for Sir Keir.

The election of a Labour government firmly in the mainstream social democratic tradition was eagerly anticipated in most of Europe, and it’s an obvious opportunity to “reset” relations. No one should expect Brexit to be reversed – much as many would dearly wish that – nor for the UK to rejoin the EU customs union or single market.

However, as Sir Keir argues, there is no harm, and great sense, in attempting to smooth off the roughest edges of the botched deal negotiated by Mr Johnson and David Frost (who seems now to denounce it), and to make life easier for Britain’s businesses, students, workers and tourists. Though relatively trivial in the great European scheme of things, some mitigation of the EU new border regime for visitors, with its €7 fee, would yield a wildly disproportionate amount of goodwill.

Yet, any fundamental renegotiation of the 2020 Brexit treaty, the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, is effectively out of the question for the foreseeable future, unfortunately. Despite his landslide parliamentary majority, Sir Keir does not have the mandate to conduct such an exercise (though he could probably get away with it, such is the disillusionment with Brexit); and the EU Commission has more urgent crises to devote its energies to – migration and the Russian menace for example.

In that context, Sir Keir is right to focus on pan-European defence and security, which he is placing “at the heart” of the new UK-Germany treaty. It is something where the EU has limited powers, and member states have more freedom of action. President Macron has been leading calls for such a new alliance.

For reasons that are painfully obvious, Europe, including non-EU and non-Nato members, has urgent need of vastly stronger defence and security cooperation. The continent has already, in a sense, been invaded by Russia, and no one can say where Vladimir’s Putin’s imperial ambitions will end.

Another unwelcome risk factor is the rise of “America First” isolationism, and the consequent weakening of the absolute security guarantee given by the US since before Nato was founded in 1949. Even if Donald Trump loses the election in November, there is no longer the same long-term certainty about the Atlantic alliance.

Is it possible that one day an American president and congress will refuse to put the lives of American troops at risk in the defence of say, Estonia or Bulgaria? If it is conceivable, then Europe has no alternative but to embark on creating a defence union in parallel with the EU’s economic and political unions.

This, then, seems set to be the central diplomatic mission of the Starmer administration – easing trade and other economic, cultural and social barriers with the European Union and, in tandem, working towards a wider defence community, one that includes nations such as the UK, Norway, Iceland and others, and possibly non-Nato members such as Ireland and Austria – as well as Moldova and, one day, Ukraine.

Such a defence community should be closely linked to Nato, and be complementary to it. It should not replace Nato, but be there if needed, just in case.

Forming a cross-continental alliance of some 30 members – and getting them to pay for its upkeep – would be a vast undertaking, but if Germany, France and the UK are soon agreed on the path forward, then that would provide the strong leadership needed to make it a success.

So this is a moment for pro-Europeans to be optimistic. The direction of travel of British policy towards Europe has changed and is plainly again towards closer integration, the gravitational pull of the UK’s largest trading partner making itself felt once more. It will not be fast or strong enough to reverse the damage done by Brexit, but it will begin the inevitable process of re-engagement, with the economic imperatives being reinforced, and overshadowed, by increasingly acute security concerns.

In large part, the European Union was founded to prevent another European war. In the coming years, the EU and the other free nations of the continent may need to find a way to fight and win a war against an insatiable, formidable foe to the East.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments