As so often with a speech from the leader of the opposition, there was little to object to and much to commend in Sir Keir Starmer’s latest bulletin on his education “mission”. The problem, as ever, is whether, for all his sincerity and sound instincts, the Labour leader really will have the right focus – and, indeed, the necessary resources – to deliver “opportunity for all” and “a country where we share a stake in every child, not just our own”.

Leaving aside the messianic overtones, the Starmer proposition will surely appeal to parents concerned not just with the cost of living crisis and their own immediate prospects, but those of their children – and indeed to anyone who takes education seriously as an engine for productivity growth and long-term prosperity.

Nations with far fewer natural resources and a weaker industrial history than the UK – such as Ireland, Finland, Singapore and South Korea – have demonstrated how an investment in schooling can transform an economy over time. It is how modern economies become and stay rich. It was also no wonder that Tony Blair famously used to preach that his three priorities were “education, education, education”, which gave a clearer signal that New Labour understood this essential truth.

Sir Keir now seeks to do the same, and he is saying some of the right things; but, as many prime ministers before him have found, it is the “doing” that will much prove the greater challenge if he finds himself in the position of leading a Labour government.

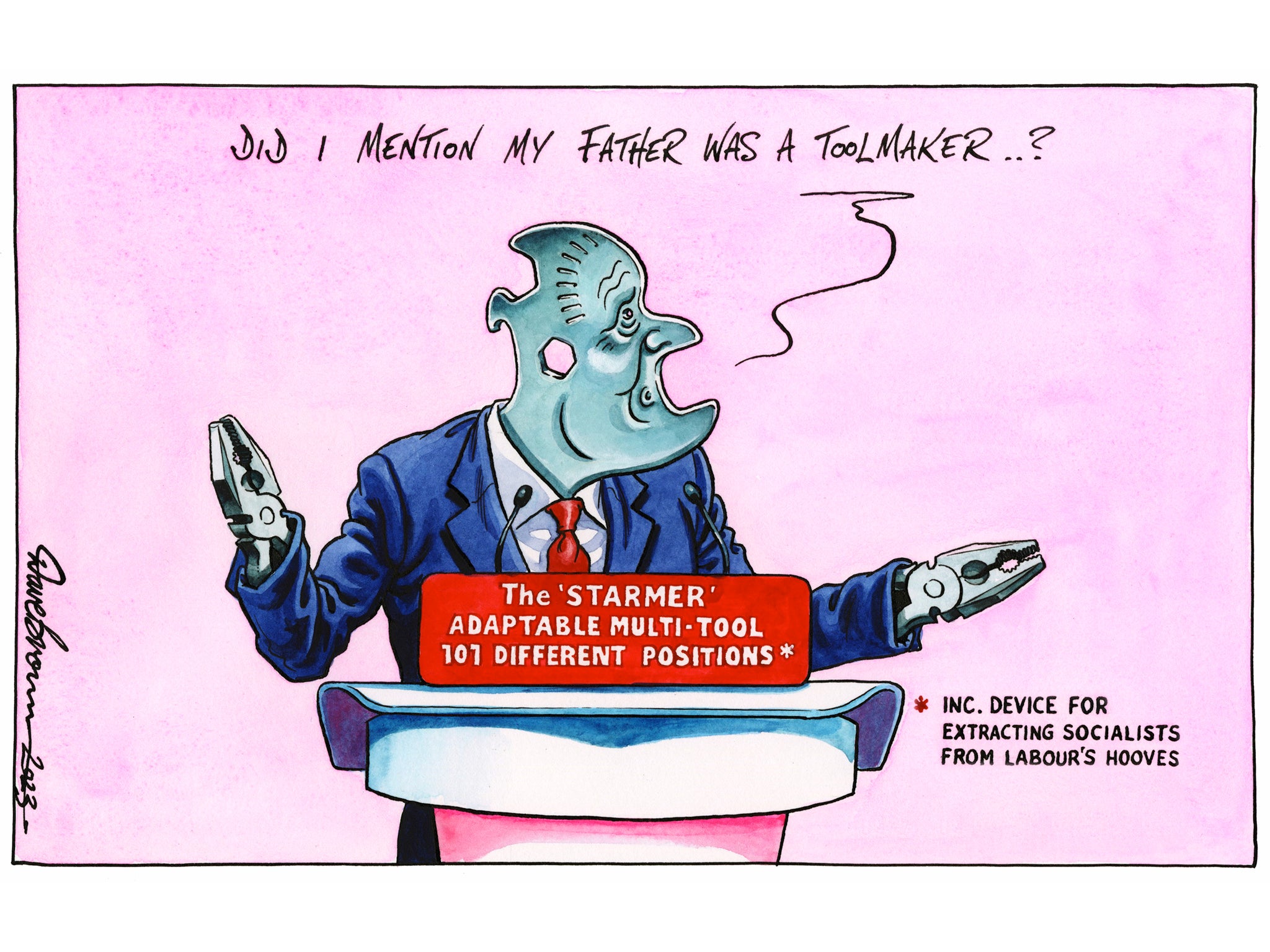

Sir Keir is as keen on reminding the public his father was a toolmaker as Rishi Sunak is on mentioning his dad was a GP. This time, though, the familiar Starmer family anecdote had a point to it. As he said, for far too long technical and vocational education and training has been the social inferior of purely academic qualifications.

So, this is a deep-seated problem that will take more than one term of a Starmer government to transform. One hopeful sign is that there is a creeping cross-party consensus that not everyone needs to get a degree in the traditional sense, and especially where apprenticeships and degree-equivalent training, especially in the new technologies, can be just as intellectually (and financially) rewarding. It would certainly be in the national interest that we should eradicate the old hypocrisy that Sir Keir calls the “’academic for my kids; vocational for your kids’ snobbery”.

Indeed, it is true that it has no place in modern society and no connection to the jobs of the future. Labour has ideas for a new body – Skills England – to help promote this change, but is less clear about how its skills plan meshes with what the job market needs, nor indeed how to divert students who want an arts degree into something that will make the UK an AI superpower. Indeed, there is also the danger that non-vocational education in good universities, which does teach young people how to think and use ideas creatively, itself becomes disdained.

A Labour leader should also be expected to promote equality of opportunity, but it was generous of Sir Keir to credit Michael Gove with the expression “soft bigotry of low expectations”, which has so long been one of the reasons why UK education and wider society remains so unequal: the “class ceiling” as Sir Keir characterises it.

On the specifics, Labour is also showing some creativity in its policy-making, and, shrewdly, looking for reforms that cost little or no money. Another rejig of the national curriculum would do no harm, especially when some parents, fairly or not, are expressing their concerns about how equal rights are being treated in the schools. Ofsted’s one-word summaries for classifying school performance may be readily comprehensible, but they do seem a rather blunt instrument to spur competition and transparency. There would surely be no harm in presenting parents with a “dashboard” to rank and select different schools according to a variety of criteria.

Perhaps the proposed Labour innovation that has caught the most attention is “oracy”, which is an ugly, academic term for a rather beautiful thing – nurturing a love of the spoken word. The English language certainly deserves it, and there’s no good reason why debating societies and prizes for speech-making and reciting poetry should be the preserve of the fee-paying sector and a few state grammar schools.

Yet Sir Keir, in his vaulting ambition, seems to have neglected some of the more basic flaws in the state system. The chronic absence rate, for instance (ie missing 10 per cent or more of lessons), remains a concern. While standards in the “three Rs” are lower than is ideal, as revealed in the UK’s PISA ranking, which is encouraging but not good enough to guarantee success in a tougher post-Brexit environment.

For such a long contribution to the debate on the issue, Sir Keir had remarkably little to say about how to pay for his dreams. He rightly earmarks some money to plug the teaching gap in Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects, but he’s extremely reluctant to discuss the pressing question of teachers’ pay, and how he’s going to improve recruitment and retention.

If Sir Keir’s speech was his entry for an “oracy” exam, he’d get an alpha minus for delivery (he’s no Churchill), a beta plus for creativity, but a gamma minus for addressing the most central and immediate problems facing the schools. A pass, then – but could do better.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments