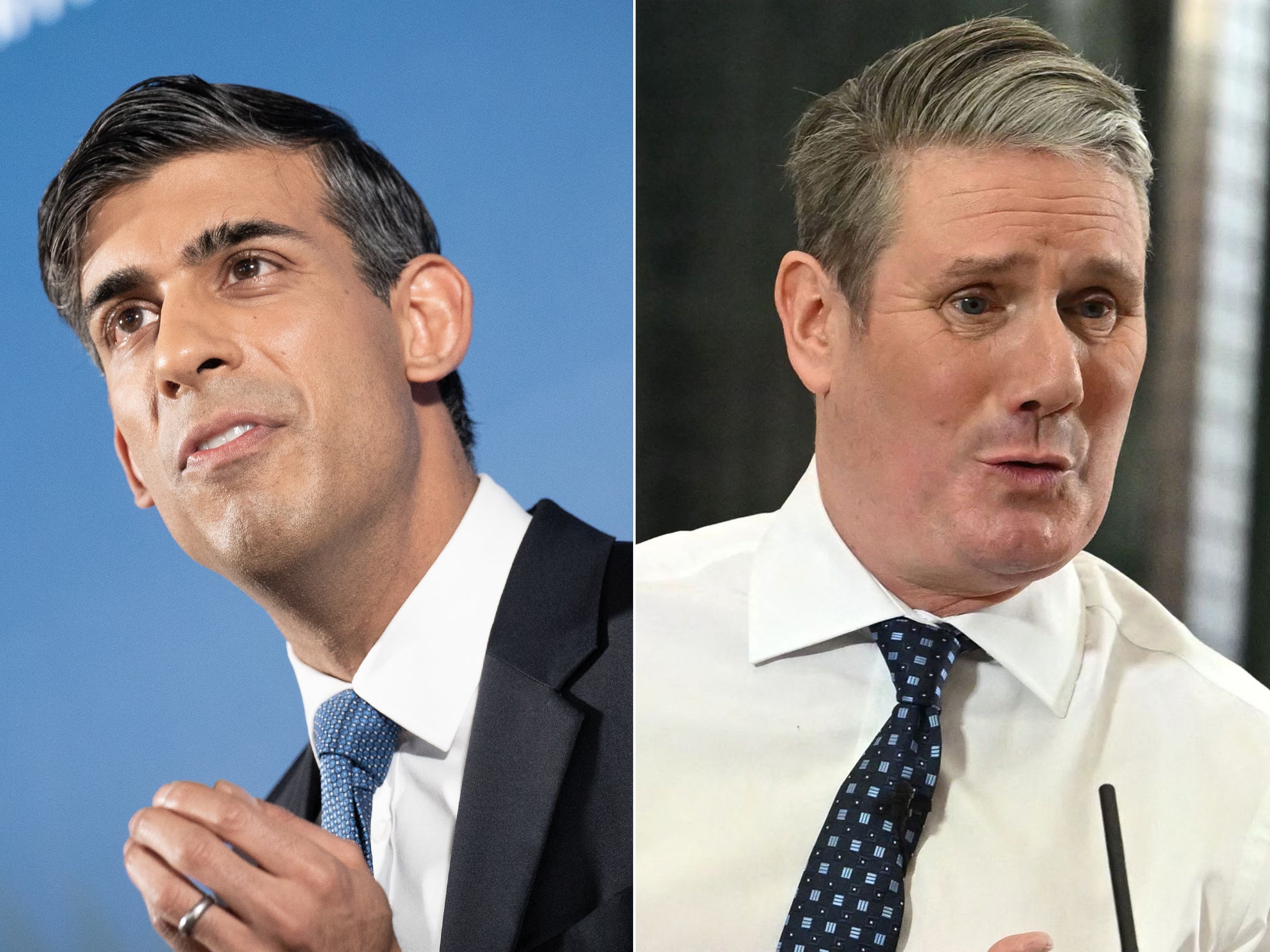

Rishi Sunak gave the more substantial speech, but Keir Starmer has the wind of the future in his sails

Who won the Battle of the New Year Speeches? John Rentoul adjudicates

My favourite moment in the Battle of the Two Speeches was when we got to the 14th question from a journalist (Martin Brown of the Express) to the prime minister, and the BBC finally abandoned its live coverage and went back to the studio so that the presenter could ask another BBC journalist what the speech meant. If only they had waited: Rishi Sunak wound up after question 15.

There is no pleasing some people. Twitter had been clogged for days with people demanding to know where Rishi was. The Daily Star, the 1980s Sun of the 2020s, asked its readers to check their sheds for the missing prime minister. It took about 60 minutes of Sunak in person for the opposite instinct to kick in and for the BBC to demand that these ghastly politicians stop hogging our screens and let BBC journalists hog them instead.

Keir Starmer managed to avoid a similar fate by giving shorter answers to questions after his speech, and bailing out at question 12. But the two speeches on successive days at the same venue (“We booked it first,” Starmer insisted) nevertheless provided a good chance to make a direct comparison of the two leaders: what messages they are trying to get across and how they respond to journalists’ questions.

If this was a preview of the next general election campaign, then it has to be said that Sunak’s speech was more substantial, but that Starmer would probably win.

The balance of advantage was clear in the structure of the speeches and in their timing. Sunak’s speech was a response to Starmer’s, although it was delivered first, as a pre-emptive strike against the Labour leader’s main message: “It is time for change.”

Hence the most important argument in Sunak’s speech was this early passage: “Politicians talk a lot about change,” he said, referring to his opponent’s speech before it was given. “But the truth is, no government, no prime minister, can change a country by force of will or diktat alone. Real change isn’t provided – it’s created. It’s not given – it’s demanded. Not granted – but invented.”

This was an unexpectedly deep and even conservative thought. That it is easy for an opposition to demand change, and a lot of voters might nod in agreement, but they might not agree on the change that is needed, or like it when a new government starts to make changes. “If we are honest,” Sunak went on, “change also requires sacrifice, and hard work.” As he said, “It’s a big risk for a politician to say that.” But his only hope at the next election is that the voters will decide that “change” is a vacuous demand, and that they should be suspicious of an opposition that appears to offer easy answers.

“Others may talk about change,” he said; “I will deliver it. I won’t offer you false hope or quick fixes, but meaningful, lasting change.” Good luck with that, the voters will be entitled to respond. But Sunak seems determined to give it a go, presenting himself as the authentic heir to the last prime minister who actually made the public services work, under whom people felt they were better off, and who made them feel proud of their country.

Yes, I am talking about Tony Blair again. Sorry about that, but the record of his successors more and more puts his record in a good light, and makes Heroes or Villains: The Blair Government Reconsidered, the book by Professor Jon Davis and me of our King’s College London course, more and more a How To guide for today’s political leaders.

I didn’t raise the subject, after all. Sunak’s speech was framed around five modest, realisable but significant promises, just like Blair’s 1997 pledge card – often mocked, including privately by Blair himself, for its lack of ambition. It was Sunak who used Blair’s language of patient choice in his promise to cut NHS waiting lists; it was Sunak who spoke of “strong communities” and who spoke awkwardly about the importance of the family, just as Blair had.

Starmer’s speech was less Blairite, although it did start with a reference to the King’s coronation year, and he tried that Blair-like tactic of making a bold raid on the other side’s territory, devoting a chunk of the speech to laying claim to the Brexiteers’ “Take Back Control” slogan.

The main parallel between Starmer’s speech and New Labour, though, was his acceptance of Conservative spending plans. One of the themes running through the speech was that Labour couldn’t promise much because there would be no money left when they made it into government. Labour would not be “getting its big government cheque-book out”, he said (he dropped the “again” from the early draft, but kept in the “its”, which implies that big spending is a specifically Labour trait).

The overall message of Starmer’s speech was that he would be doing his utmost this year to convince voters that a Labour government would make better use of limited resources than a re-elected Sunak administration. Yet I thought Sunak’s pre-emptive strike was effective: he put forward a better claim to an attempt like Blair’s in 1997 to make a positive difference to the country with no increase in borrowing.

Starmer’s refusal to make any specific promises should have made his New Year offering less appealing, but the Conservatives have done so much damage to their reputation over the past year that he may find a vacuous “time for change” message is all Labour needs.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments