Two words for Ofsted’s inadequate one-word ratings for schools: good riddance

The scrapping of Ofsted gradings means that the education system has in Bridget Phillipson a secretary of state who is plainly in command of her brief, says Sean O’Grady

I have always wondered how it can be that an organism as multi-faceted, complex and dynamic as a school can be adequately summed up usefully in a one- or two-word description.

Common sense tells us that it is a bit silly – and spectacularly so, when applied to something as crucial and life-chances-defining as the choice of a school. No human being, no institution, not even a car or a restaurant, can really be boiled down to the four, crude categories employed by Ofsted inspectors: Outstanding; Good; Requires improvement; Inadequate.

For example, most parents would surely find it rather, well, unsatisfactory, if they received an end-of-year report on their offspring that was headlined in such a way: “Emily: Inadequate.”

True, there may be various sub-categories and another 1,400 words or so of detailed, discursive assessments to bring out the nuances, but the final verdict is the one that everyone will know and remember – and many will not read on having been confronted with such a damning indictment.

And “inadequate” is such a harshly pejorative word too, isn’t it? Buried under that boulder of a word could be a brilliant music or drama department, or a place where the students feel safe, in every sense. It is hard to believe that it helps any school make things better. It might well make the teachers give up and want to get the hell out instead.

As the tragic case of Ruth Perry shows (she was the head who tragically took her own life when she and the school she led were thus humiliated), such ludicrously oversimplified assessments can do far more harm than good. You wouldn’t dismiss a genius maths scholar who is bored and hopeless at history as “overall average”. Why pretend you can do so with a whole school?

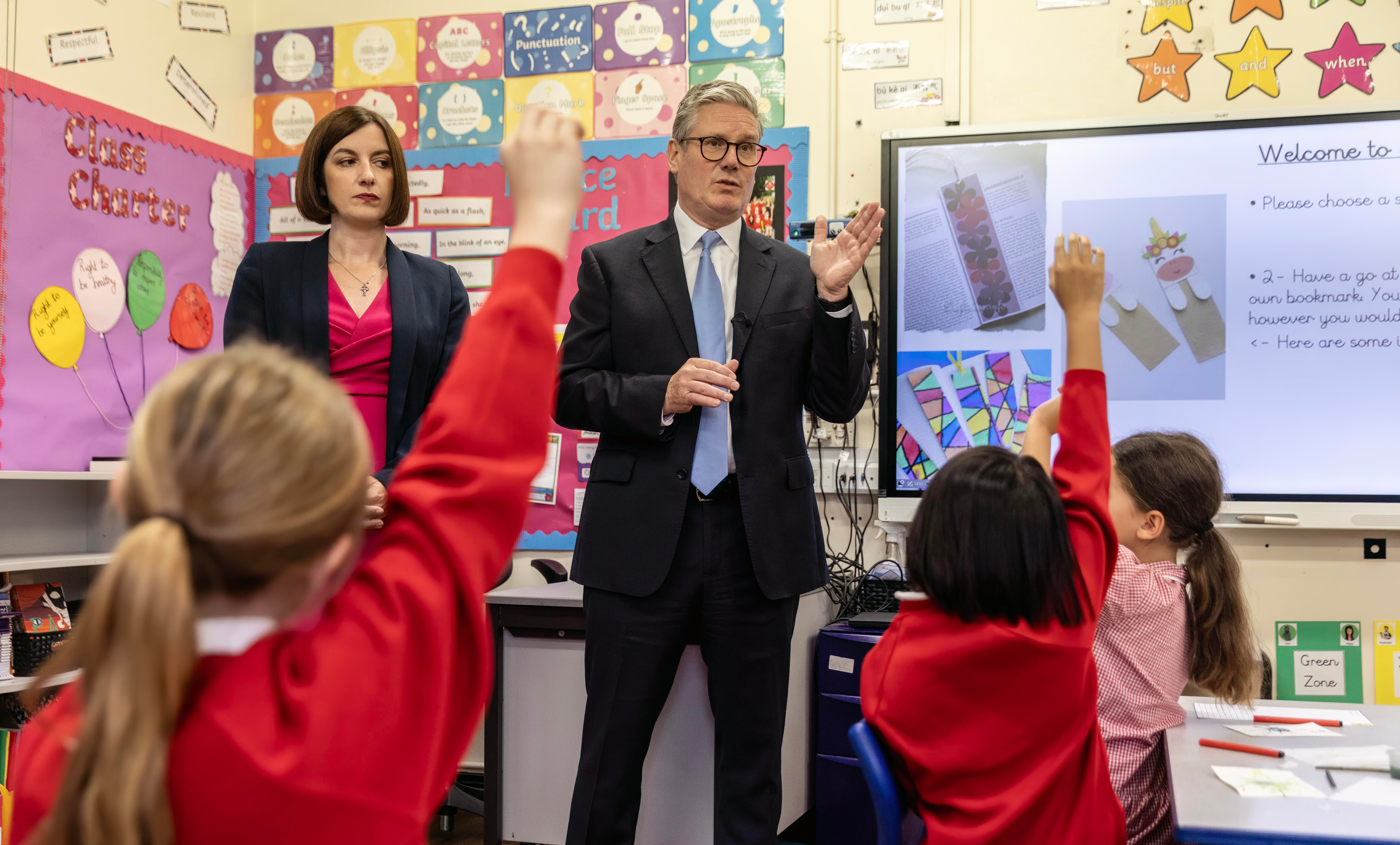

It is right that a new minister in a new government, Bridget Phillipson, should look again at the system. This impressively pragmatic politician has decided that the Ofsted grading system was itself inadequate and required improvement. About time.

Of course, it is argued that the old system was easy to understand and told parents all they needed to know without bamboozling them about demographically adjusted stratified exam performance, or nebulous concepts such as creativity or community. If so, then maybe we should make things even easier for busy parents and have categories of “the good, the bad and the ugly”, or, like an MoT, “pass” and “fail”.

I can’t see that being better just because it is even simpler (or simplistic). You wouldn’t buy a vacuum cleaner on Amazon based only on the star rating. You’d want to read other buyers’ experiences, say, and the range of scores, in terms of their consistency, and what suits your own needs. Likewise, when you buy a car, you need to decide what’s most important to you: performance, styling, space, reliability or comfort. Even a TV show cannot very accurately be reduced to a one-word review or a star rating out of five: the Mrs Brown’s Boys Christmas special makes life worth living for some people, while being an intolerable cultural trauma for others.

It’s true that an Ofsted report contains plenty of information for parents who care to plough through it, but even here it’s not always going to be that robust or informative. It could be out of date, given that inspections aren’t frequent, and a school might have a freakishly good or bad year in the public exams.

The criteria are a bit curious, too: “Quality of education”; “Behaviour and attitude”; “Personal development”; “Leadership and management”. Surely these are not independent variables? There can be no “quality of education” without the other three being fulfilled. Would a school with a serious knife crime problem boast amazing exam results? What exactly is “personal development”, and how is it assessed consistently by scores of different inspectors across England?

Given the paranoia that surrounds schooling these days, and the competition for places, it is hard to remember a time when there were just school inspectors, and there were no public league tables and little naming and shaming of schools. Yet the kids still got taught and managed to pass their O-levels.

We live now in a more suspicious, demanding age of parental power. It is a national scandal that teachers aren’t trusted to get on with the job, and are, ironically, ceaselessly bullied by pupils, parents, politicians and watchdogs alike. The panoply of Ofsted inspections grew out of a culture of demonising and devaluing the teaching profession, making them the scapegoats for the real problems – yes, “inadequate” parenting and “inadequate” funding provided by “inadequate” education ministers.

Now, for the first time in a while, the system has in Phillipson a secretary of state who is far from “inadequate”. She is plainly in command of her brief, even at this early state, harbours no ideological hang-ups, and is capable of making a decision and sticking to it. If it’s not too simplistic a word, she may yet prove to be outstanding.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments