Why the West should worry about the end to the Putin and Xi summit

This visit may end up being seen as a unique, landmark, occasion: the point at which the global centre of gravity started seriously to shift from West to East, believes Mary Dejevsky

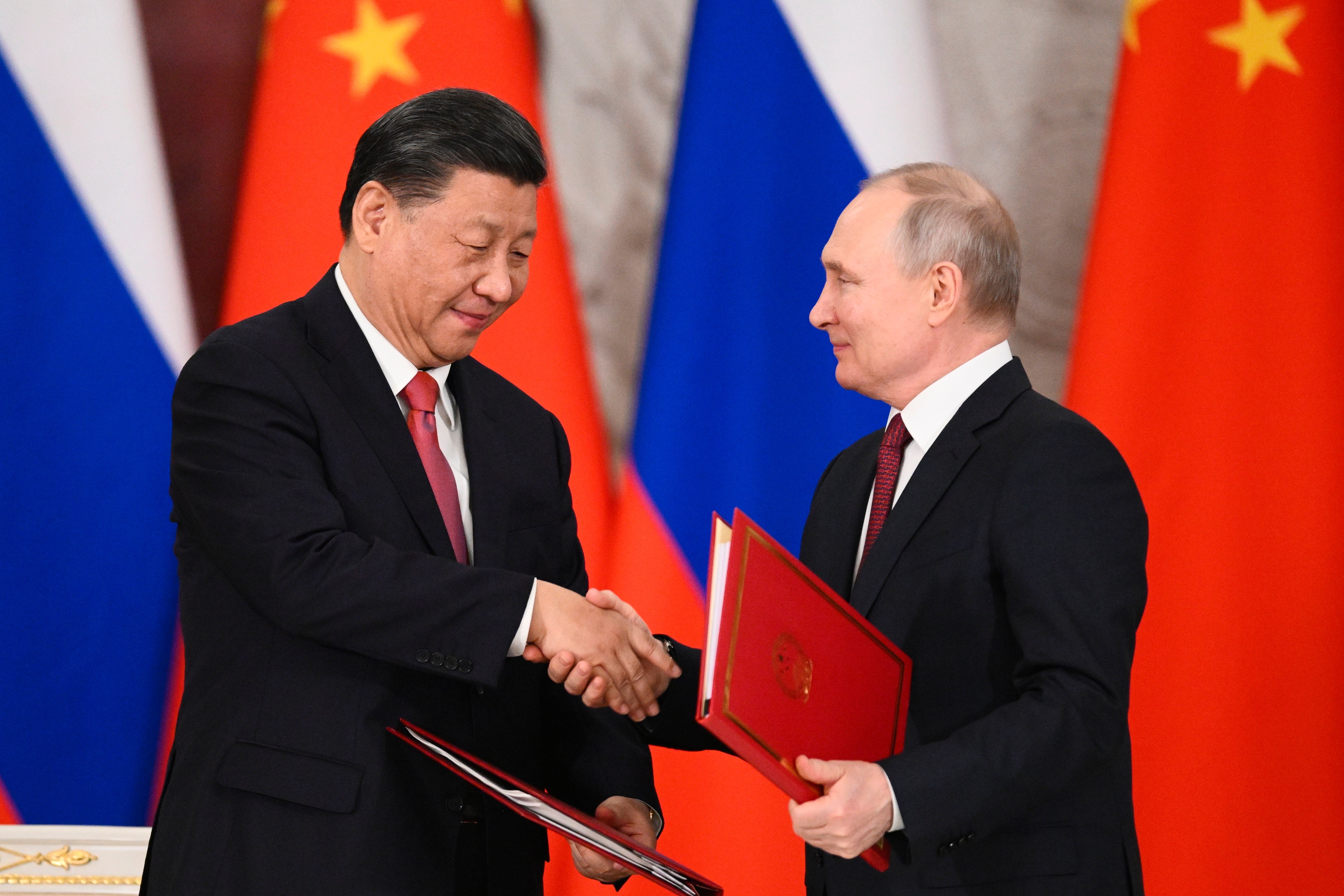

This week’s Russia-China summit in Moscow was not unusual in itself. Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping have met many times more, and less, formally. They appear to have established an amicable and straight-talking relationship – their discussions were described by Putin at their closing press conference as “frank, open and friendly”.

Viewed through the longer lens of history, however, this visit may end up being seen as a unique, landmark, occasion: the point at which the global centre of gravity started seriously to shift from West to East.

It is a shift that the United States has long prepared for and dreaded. There was a wariness with which Washington, in particular, has looked on from a distance. There were, to a degree, three at this summit, even if the summiteers acted between themselves as though the United States was not there. The stage management may primarily have been for each other; but the size of the flags, the height of the doors and the length of the red carpets were all designed by Moscow to impress not just China, but to project the solidity of the Russian-Chinese relationship to the Western world.

This is not, it should be stressed, an alliance, military or otherwise and will probably never be. Nor should Putin and Xi be regarded as close friends, for all that they were once filmed making pancakes together and are almost exact contemporaries: Putin in 70; Xi - 69. This is a cool-headed relationship for mutual benefit and in mutual interest. It is also a relationship in which the advantage, while quite evenly balanced, may subtly have turned.

Russia pulled out all the stops for Xi. From the airport arrival to the banquet to the signing of the joint statement and their press conference, this was at the very top end of Russia’s ceremonial register. And the joint statement indicated that they were parting, having achieved pretty much what each of them wanted.

Putin got the pictures he wanted. He was hosting the leader if not of the most powerful country in the world right now, then of the country most likely to be the most powerful before long. The pictures, and Putin’s relative ease alongside Xi, told the world that any ambition the West might have had to ostracise Russia after its invasion of Ukraine had come to nothing.

There was demonstrative value for Xi as well. China has suffered an increasing barrage of hostile rhetoric from the United States, most recently over the surveillance balloon incident. It is useful for Xi, too, to show that he has friends.

The other priority, for both, was trade and economic relations. The Chinese market, especially its energy market, has been a boon to Russia in the wake of its exclusion from much Western commerce. Agreements signed in Moscow... provide for what, even in the context of two very big countries, constitutes a major commitment to increased trade, including transport, logistics and energy. How far this will come to pass, of course, is another matter. But the intention is there and the two economies can be usefully complementary if both sides so choose.

But trade, while a genuine priority for both, has also to be seen as displacement activity for political relations that could reveal tensions were they not to a large degree eclipsed by trade. Which is where Ukraine comes in. During the year since Russia’s invasion, Beijing has walked a delicate tightrope between disapproval of the invasion as a breach of international rules, opposition to Western military support for Ukraine, and not wanting to rock the boat with Moscow.

In common with India and a host of smaller states, referred to as the “global South”, China had abstained from UN votes that condemned Russia. China also feared the spread of hostilities, with the risk to international supply lines and talk – from both Russia and the US – that there could be a resort to nuclear weapons. All these were reasons why China might have formulated the 12-point “position paper” on peace for Ukraine that it published on the anniversary of the invasion.

The good news – good news that is for those who believe, as I do, that an early end to the fighting in Ukraine has benefits for Ukraine too – is that China’s peace plan is still alive and appears, within some careful limits, to have Putin’s support. What he said was that “many provisions” of the plan could be “taken as the basis for settling the conflict”. It should be stressed as well that the plan has not (yet) been dismissed by Kyiv.

How realistic a prospect it is, however, remains in question, and there were some loud noises as the ceremony proceeded in Moscow. They came primarily from Washington, and they warned of a trap designed to bring Kyiv to the negotiating table at a time and in military circumstances that favoured Russia. This produced what might have seemed to some a strange dissonance, with Western interests calling for more war, and the East, in the shape of Russia and China, advocating peace.

One of the basic questions is how much Putin really wants peace and on what terms Russia might settle. On the eve of Xi's visit, he had appeared open to peace talks, in an article for China’s main official paper, the People’s Daily, although he condemned Ukraine’s demands to reclaim all the territory it had held before 2014. His language at the joint press conference suggested a tad more flexibility – talking of a settlement “whenever the West and Kyiv are ready for it” although only time will tell if that is actually true. Whether this apparent change was at China’s persuading, we may never know.

For the time being, China’s peace effort survives. It has not yet been killed by the US, much as it would clearly like to see it expunged, nor by Moscow, which might – just – be looking for an escape route. Whether it goes any further may depend on Kyiv, with Xi reportedly planning a “remote” call with Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky.

That the plan survives, however; that Moscow may have given just a little ground, and that no mention was made of Chinese weapons for Russia, leaves the impression of a Russia that is just a little weaker. And this seemed to be reinforced by the body language. Although he was the host and the master of the show, Putin seemed fractionally deferential to his burlier and more jovial guest. There was just a hint that Putin needed this visit that bit more than Xi did, and that the tables of seniority and, yes, power, might have turned.

From now on, the balance of power may have begun to shift not only from the West to a land axis in the east, but from Russia to China within that axis. Any peace settlement in Ukraine will appear to Russia as the last stage of the Soviet Union’s long disintegration being complete. Not for nothing did Xi say, standing beside Putin, in Moscow that China “stands on the right side of history”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

55Comments