Whisper it, but Labour don’t have a plan to fix this Tory mess either

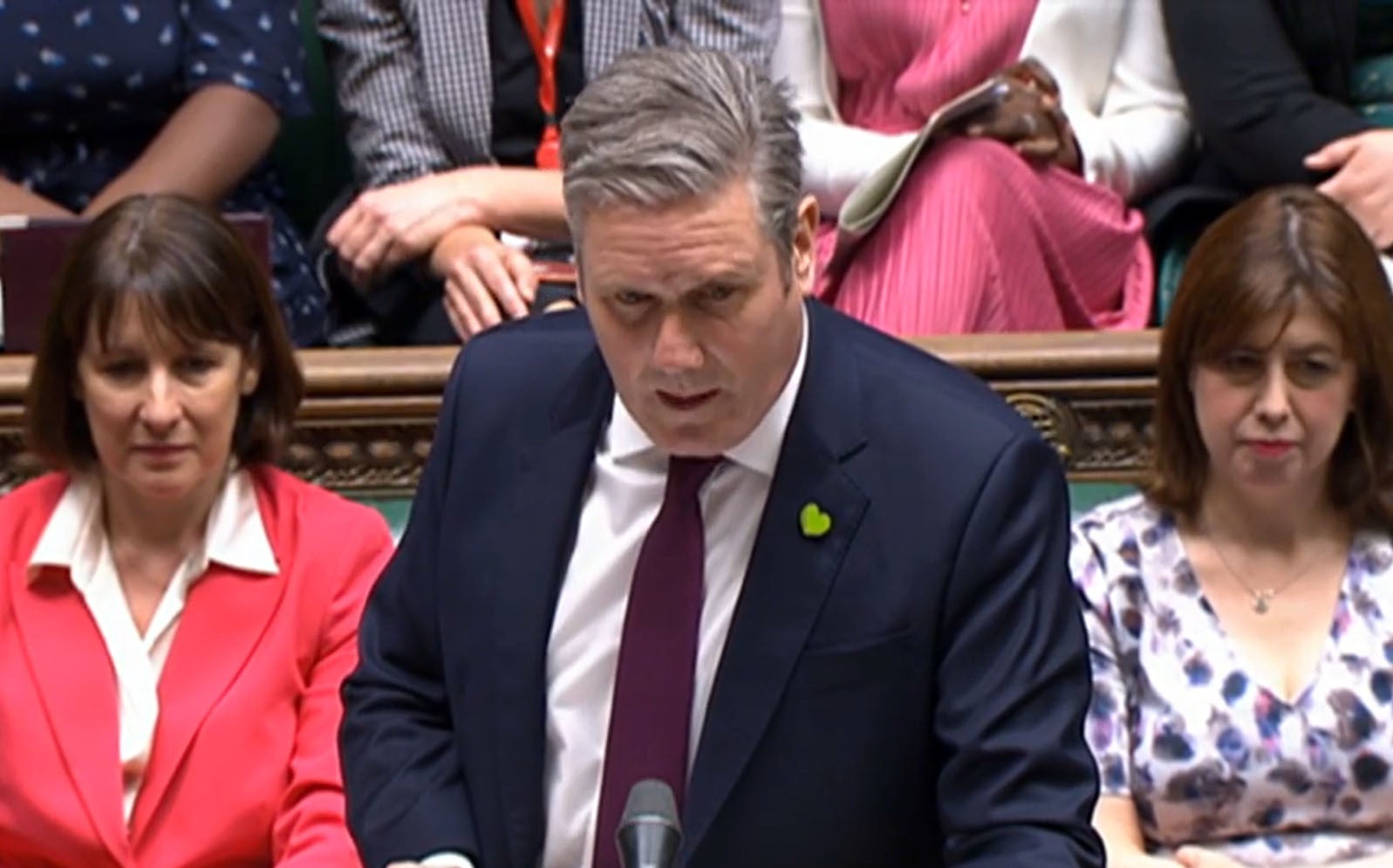

Clunky Keir Starmer spent PMQs trumpeting away at ‘the Tory mortgage penalty’ and moneybags Rishi Sunak, but for all his bluster the would-be PM is noticeably thin on ideas of his own, writes John Rentoul

It was effective, but it wasn’t pretty. Keir Starmer repeatedly referred to “the Tory mortgage penalty”, which he said was caused by “Tory economic failure”. This is facile sloganising rather than economic analysis – even if it seemed to hit the mark.

The irony is that a Labour government would have done no differently in recent years. Labour supported the furlough scheme during the pandemic and advocated energy bill subsidies shortly before the government brought them in. Those are two big causes of the weakness of the public finances and, as Rishi Sunak said, the problems of high inflation and interest rates are common to most countries.

The prime minister didn’t admit that the UK’s situation seems worse than that in many countries, choosing instead to cherry-pick statistics about interest rates being similar in the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. But the reasons for differential economic performance between countries are complicated, and Starmer did not identify any policy decisions since Brexit – and he was certainly at pains not to mention Brexit – that had caused the UK’s relatively poor performance.

Nor did he advocate any different policies for the future. On interest rates specifically, Labour has not followed the Liberal Democrats in arguing for further government subsidies for mortgage payers. Instead, it advocates the same ideas that the government is discussing: lengthening mortgage terms and encouraging a flexible approach by lenders to borrowers under stress. Hardly stirring stuff.

One of the few policies that Labour does have that is different from the government (and indeed from the Lib Dems and the Scottish National Party) is that it wants to end new licences for North Sea oil and gas exploration. Rishi Sunak said that this would “make the situation worse”. He at least engaged in a debate of substance when he said of Starmer: “He doesn’t have many policies, but the few he does have one thing in common: they would be dangerous and inflationary.”

Starmer, on the other hand, offered only slogans, froth and insults. He and Rachel Reeves have decided to dish out to the Conservatives what David Cameron and George Osborne threw at Labour in 2010, accusing the Tories of “crashing the economy”, despite having broadly supported the government’s policies. Chris Mullin, the high-minded and free-thinking former Labour MP, commented in his recently published diaries that he “hoped” Labour would avoid sinking to that level, but he has misjudged how politics works: slurs stick, even when they’re baseless.

The gift that allows Labour to get away with it is what Reeves calls the “drive-by premiership” of Liz Truss. Last year’s disastrous mini-Budget, which spooked the gilt markets and caused mortgage lenders to withdraw their products, gave the impression that the government had driven the car off the road – even though Jeremy Hunt quickly grabbed the steering wheel and got it back on course. Little lasting damage was done, except to the government’s reputation: the markets quickly recovered; interest rates went back down and have only now gone up in line with world trends that would have happened anyway.

But the Truss wobble now serves for Labour the same purpose that Liam Byrne’s 2010 “I’m afraid there is no money” note served for the Tories for so long: a trumped-up charge that the government lost control of the economy.

The Labour leader ramped up the insults. He said Sunak had a “keen interest in the mortgage market in California”, and that he was too removed in his helicopter from the “lived experience of those on the ground”. Any cutting edge was blunted by Starmer reading out his lines, and he allowed the prime minister to take the high moral ground by disdaining “personal attacks”.

But Starmer’s clunky politics-by-numbers is nevertheless effective. The voters blame the government for high inflation and high interest rates, whatever their causes, and regardless of their support for the huge borrowing of recent years to protect people’s jobs and living standards.

Starmer is getting rid of the remaining distinctive Labour policies that would make matters worse. The £28bn-a-year extra borrowing for green investment has been ditched because Reeves accepted that it would push interest rates and inflation up even higher. The ban on North Sea oil and gas exploration is one of the few policies left that could be a liability if it means more gas imports in the later years of the net zero phase-down to 2050.

But the real story of today’s Prime Minister’s Questions is hypocrisy: that the opposition is successfully blaming the government for economic woes that it, too, would be facing if it were in office, and for which it has no solutions. No matter. This is what happened before the elections of 1970, 1997 and 2010: in each case the government took the right and responsible decisions in the national interest, for which it reaped insufficient electoral reward. In each case, the opposition party had no answers but won the election because the voters decided that it couldn’t be any worse.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments