When the ‘fat cat’ pay gulf is this big, is it any wonder we’re facing a winter of discontent?

Pay disparity in the UK is extreme, writes Alan Rusbridger. So why are we so outraged by the idea of essential workers getting a fair shake while super-earners get ever richer?

Let’s start 2024 with some good news – especially if you happen to be an aspiring corporate lawyer.

You may think that the cost of living crisis hasn’t really touched m’learned friends, but you’d be wrong. My eye was caught by an article in New Year’s Eve’s Financial Times about how the Ritzier end of the legal sector was coping with the fiscal stresses and strains we’re all going through at the moment.

There is currently a slump in demand for high-end legal services (blame sluggish M&A markets), but City lawyers are famous for having hearts of gold, and have responded by handing out super generous pay rises and bonuses to help their colleagues through these tough times. You’ve gotta love these guys.

“In light of the cost of living, we thought it made sense for the industry to pay higher salaries and we wanted to be a first mover in instigating that,” said Scott Edelman, chair of Milbank, a US law firm.

Over at Cravath, a beginner lawyer who graduated in 2023 can expect to start at $225,000. Someone who graduated in 2017 – ie around 28 years old today – can now expect to earn $420,000.

You’ll be relieved to hear that this doesn’t include bonuses. If you’re around 29 and work at, say, Boies Schiller Flexner, you can pocket $435,000 with a bonus of $115,000.

The trend, reports the FT, is not limited to US firms. UK “magic circle” firms will also pay their US lawyers in line with this kind of moolah. And a globalised market for legal services means a rising tide that will float all boats.

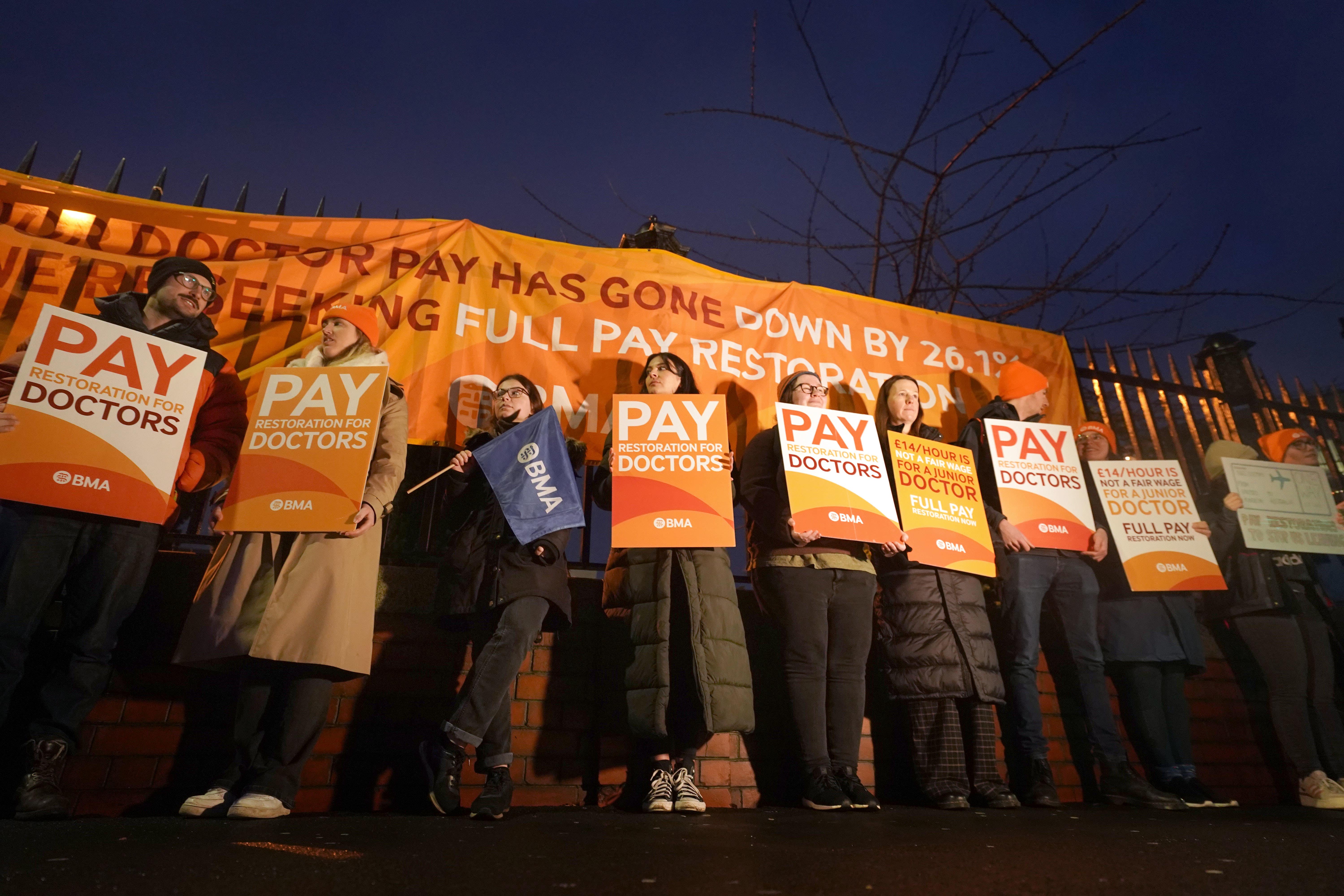

If you’ve been a listener to phone-in programmes over the past few days, you’ll have been asked your opinion of the striking junior doctors. Greedy chancers, or salt of the earth saviours?

According to the Nuffield Trust, a first-year doctor can expect to start on around £32k basic – around £41k all-in. Which is around £134k less than their counterparts and contemporaries in corporate law. Not counting bonuses.

I don’t know about you, but I feel that we would, as a species, miss having doctors around more than we would corporate lawyers. But you’d be surprised the number of callers who think the former are avaricious leaches.

But never mind apple and pear comparisons between different professions. Let’s compare apples with apples, lawyers with lawyers.

You may have read that the legal aid system is on its knees. Another helpful article in the FT just before Christmas reported on a court challenge by the Law Society over the refusal of the government to implement the pay recommendations of an independent review.

That independent review – by Sir Christopher Bellamy KC in 2021 – found that solicitors doing legal aid work were between 35 per cent and 50 per cent “worse off in real terms” in 2021 than they had been in 1996.

A legal aid solicitor can expect to earn around £32,500 – less than a tenth of what they might expect to earn if they were toiling into the night on a merger or acquisition.

Time for small violins? But, as Sir Christopher said in his report, this is more than just an argument about pay. The adversarial nature of our criminal justice system relies on having defence lawyers (a great many of them in legal aid) as well as prosecutors. If legal aid is no longer working, then the entire system begins to break down.

Again, I can only speak for myself, but I don’t welcome the prospect of the criminal justice system collapsing – even though it is, by all accounts, pretty much on its knees already.

Forgive me if by now you are muttering, “yes, yes, but what’s to be done?” For it is surely the obligation of a columnist to come up with trenchant solutions.

But I don’t know what there is to do about law firms offering riches beyond imagination to young kids just finishing their studies. I loathe the idea of it, but I’m not sure what could realistically be done to curb it.

I feel intensely uneasy at living in a society where care workers earn £12.08 an hour at the same time as the average FTSE 100 CEO earns 80 times the median salary of their staff. Or that the UK has more millionaire bankers than the whole of the EU put together while our economy stagnates.

It feels wrong to me – and, I suspect, to most people. The vast majority of people (76 per cent to be exact) believe top earners should not be paid more than 20 times the salary of their low and middle earners. Yet here we are.

In the UK, we live in a hybrid economy where late capitalism jostles uneasily along with broadly underfunded public services. In the 1970s, Britain was one of the most equal of rich countries. Today, it’s the second most unequal, after the US.

“The evidence is that if you have people at the top taking more, there is less to give out for everybody else,” says Oxford professor Danny Dorling, who has spent much of his career studying inequality.

Maybe it takes a legal brain to find a solution to how we put a proper value on public services. So here’s my proposal: we take a dozen wealthy magic circle lawyers and lock them in a room – it can be a pleasant meeting suite in their swish offices – until they have found a solution to funding legal aid lawyers at the other end of the scale in their own profession. To, you know, prevent the collapse of the criminal justice system.

We can even give them a bonus if it proves workable. Happy New Years all round!

Alan Rusbridger, a former editor of The Guardian, is editor of Prospect magazine

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments