50 years on, many still carry a torch for The Wicker Man

The wonder and weirdness of the radical 1973 film has a strange effect on everyone who experiences it, writes Stephen Applebaum

The Wicker Man is the film that refused to die. Greenlit by Peter Snell, a young production head at British Lion, who had “gone rogue”, according to one of the director’s sons, Justin Hardy, the film was hastily re-edited and slipped into UK cinemas in 1973 as the lesser half of a double bill with another Snell commission, Don’t Look Now.

The latter is a “proper masterpiece”, says Justin. However, 50 years later, it is his father Robin Hardy and screenwriter Anthony Shaffer’s “odd genre mash-up of a film”, set on the fictional Scottish island of Summerisle, that is being celebrated and revamped for the 21st century.

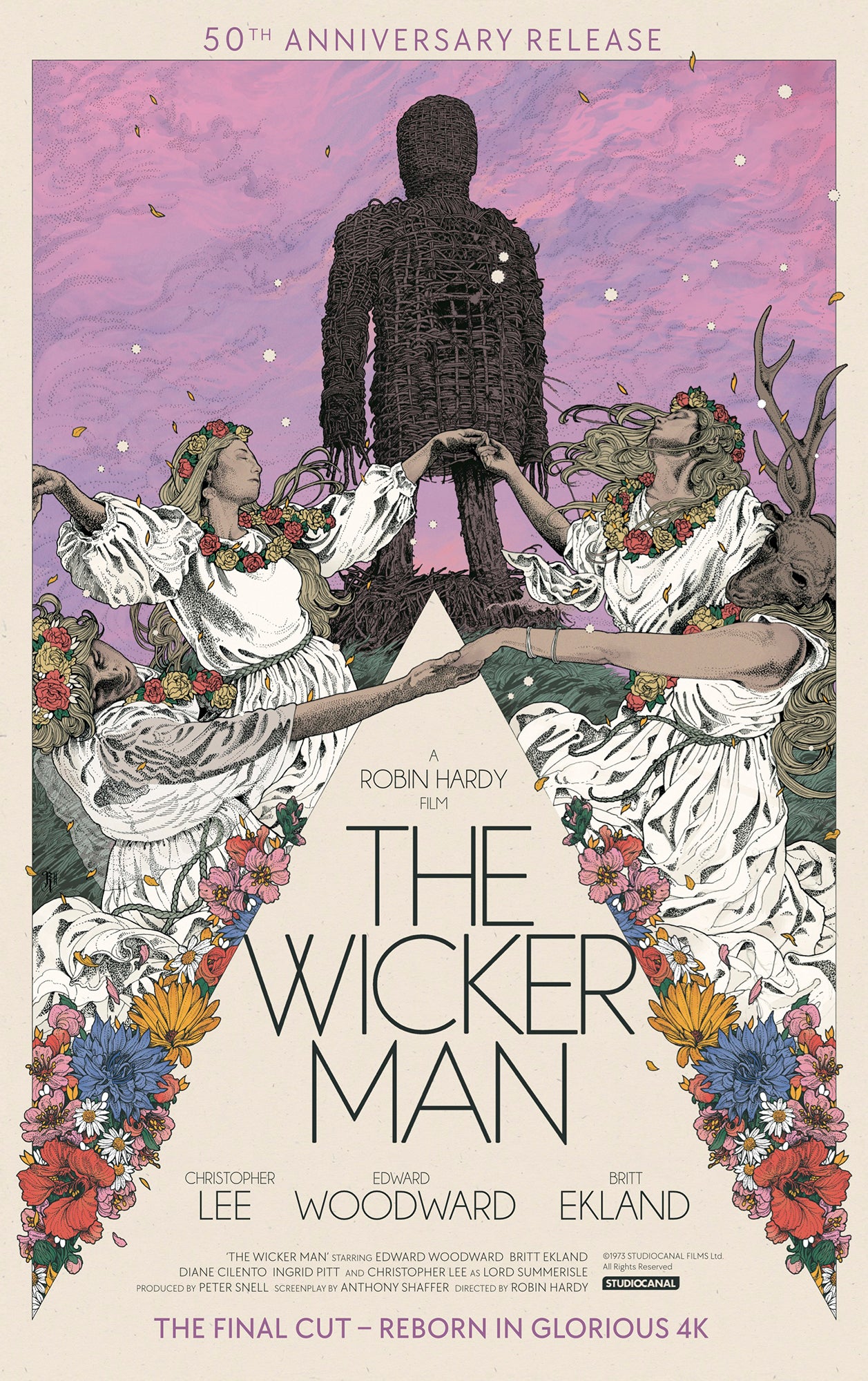

On 21 June – the date of this year’s summer solstice – a 4K restoration of The Wicker Man: The Final Cut will be released in cinemas nationally, for one night only. Three days later, Musics from Summerisle, at the Barbican, will feature Lesley Mackie, who appeared in the film and sang on the soundtrack, as well as on the soundtrack CD, in the first authorised performance of almost all of the late composer Paul Giovanni's evocative music from the film.

In the longer term, Howard Overman, the creator of Misfits and a 2019 adaptation of War of the Worlds, is writing a TV series for The Wicker Man that he says will use the title and themes, but – and I think wisely – it will not be a remake. When the director Neil LaBute and Nicolas Cage tried that for cinema in 2006, "puzzlingly misguided” and “entertainingly bad” were some of the critics’ kinder remarks.

“The director had done some good stuff and obviously Nicolas Cage had, but Jesus Christ,” says Overman, laughing. “The takeaway is don’t try and remake beloved films. You just p*** people off.”

Justin Hardy declares himself “frankly astonished” at the continuing interest in The Wicker Man and the way that it has become embedded in people’s imaginations.

“It’s incredibly impressive that a film about a made-up story set in a pagan landscape, a folk horror, a bit of potential hokum, has just lived on as if it were an utterly, utterly real part of our British cultural landscape,” he says.

It feels fitting, however, that a film in which a devout Christian policeman, who is sacrificed by modern-day pagans and talks about “resurrection” and “the life eternal”, virtually disappeared, and then, by way of grassroots screenings in America, returned home years later as a cult film.

“A lot of people have said that the Southern Baptists liked it first, partly because they wanted to see a martyr,” says Justin. “And then the hippies from the West Coast liked it because they wanted to see the killing of a pig [ie police officer].”

The wonder and weirdness of The Wicker Man has a strange effect on everyone who experiences it.

“No film has attracted more completely disparate opinions and memories than this film, apparently,” says Justin. “The BFI confirm that. They say it’s part of the magic – nobody agrees on anything.”

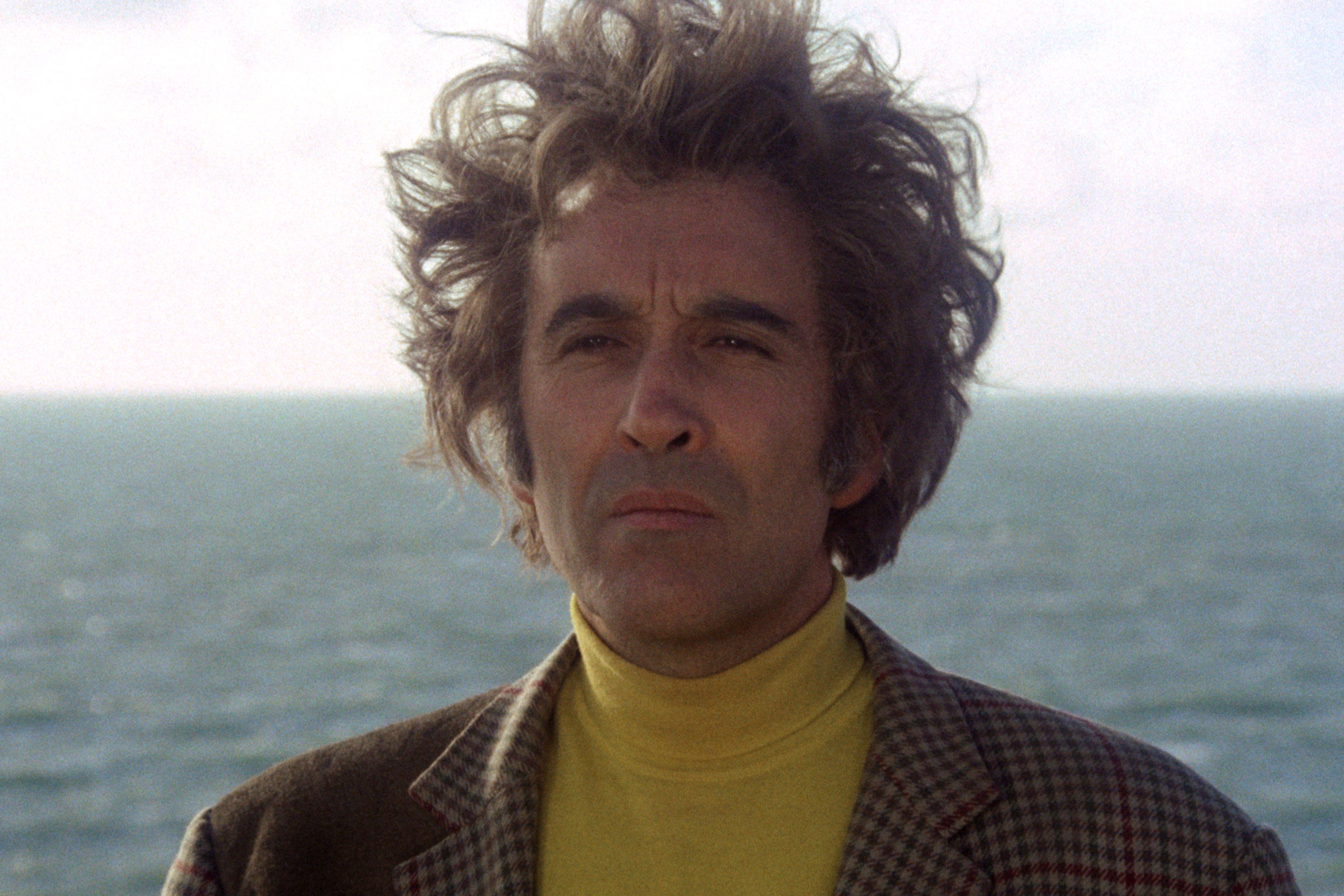

It’s true. When I interviewed Robin Hardy, Anthony Shaffer, and Edward Woodward – the actor who stars as Sergeant Howie, the unwitting sacrificial copper – back in the 1990s, their recollections were frequently contradictory. Lesley Mackie, who plays Daisy in the original and will be part of the performance at the Barbican in June, describes the film’s production as “chaotic”, so it is not entirely surprising that people’s memories of it are as well.

The chaos will be part of Wickermania, a documentary that Justin Hardy is making with his older half-brother, Dominic, and Christopher Nunn, a friend he met when they were teaching at the University of Greenwich while finishing their PhDs. Currently a work in progress, Justin says “it’s about the condition of madness in which the film was made – and certainly our father was in a condition of madness – tied together with some of the mania with which the film has been received ever since.”

He did not come at the project out of affection for either The Wicker Man or his father. In fact, it felt like being prodded in a wound whenever people praised them to him.

Robin Hardy had produced and post-produced the film in the family’s then home in London, when Justin was a child, and it should have brought them joy. Instead, it tore them apart.

“When it flopped, Robin Hardy left my mother and me and my sister. He came to see me at my school and said, ‘You won’t be seeing me for a while. The film has done very badly and I’m leaving.’ I then didn’t see him for five years, while he helped resurrect it in the US. I thought he was dead.

“So, I have no reason to love The Wicker Man,” continues Justin, his tone a mix of anger, sadness and hurt. “My mother lost her marriage. We lost our house, our home. Our family never made any money from it. It didn’t put any food on our table. It was a pretty barren landscape.”

Imagine, then, how he must have felt when a woman wrote to him out of the blue during lockdown, saying she had found letters, storyboards and scripts from between 1970 and 1974, pertaining to a film called The Wicker Man. “Would you like them or should I throw them on the fire?” she asked. Not long after, six sacks “dutifully arrived” on his doorstep.

“Those papers were decamped from the office in London, which was in our house, and ended up in an attic in one of the houses [we moved to], and then eventually found their way, kind of rather magically, back to us.”

The sacks “sat staring at me in a corner,” he says. “I didn’t really want to open them, and could almost hear the ticking bomb inside. But it’s like, ‘Jesus, do I really want to deal with this stuff?’”

They had arrived around the same time as Justin and Nunn started thinking about doing something for the 50th anniversary, focusing on fans and the film’s enduring legacy. They did a shoot in Birmingham with some academics, and then a few days later, Nunn recalls, Justin swallowed his fears and opened the sacks.

Inside was an archive of primary materials that “told a different story”, says Nunn.

The papers reveal Robin Hardy “with a clarity” that Justin and Dominic had never seen him in before, “and it is often quite painful”, says Justin. Not only was their father struggling with the challenges of shooting a film set in spring in the Scottish winter, but he was going bankrupt at the time and “clinging on to being the director at all. He was a first-time director. He was falling out with the heads of departments. He was extremely isolated. He fought extremely hard to survive through the shoot.”

They “infer” from the documents that Hardy would probably never have been in the director’s chair but for Shaffer, with whom he’d been partners in an advertising firm. Shaffer was putting the film together with Snell and Christopher Lee, who would play the brilliantly sinister Lord Summerisle, and Hardy begged him for a shot.

He had had a heart attack, which should have disqualified him from directing because of issues around insurance, but Shaffer kept quiet and vouched for him anyway. The writer threw his friend a badly needed lifeline, although they would later fall out.

“Dad’s office notes tell us of this terrible state that everything was in,” says Justin. His advertising business had accrued debts and their mother, “who had basically funded him, was right on the edge herself. She had bled every last penny. And by the time this film finishes, she goes bankrupt, too, and loses everything. And so there’s this story of what it costs to make an independent film.”

Justin asked Dominic – who has a different take on things because he grew up in North America where The Wicker Man became a hit – to join him on the project, which has evolved into a search for their father, through his film.

“We’ve come at this process from these different perspectives, and that in itself, I think, has probably been quite painful,” says Justin. They agree that Nunn has been invaluable as an objective participant. This has meant sometimes stepping in between the siblings as they “kind of wrestled with each other”, Justin admits, and “sometimes trying to make sense of our emotional angst”.

Dominic says working together has brought them closer. Justin, in particular, though, is still grappling with his demons. He recognises that his father helped make something that has “created love from fans”, but for a long time has not been able to grasp that love himself. He would like to, though.

“I’m learning to try and kind of catch a bit of that, and say, ‘Well, if you love this film so much, can you share that with me so I can try, you know, love my dad too?’ We’re just looking for our dad. We’re looking for a bit of that. Like we all are.”

He may have found a way. As a filmmaker himself, he has begun to view The Wicker Man from a new perspective, through the “prism of radical ideas and radical notions”. Where once he looked at it and saw “a series of potential errors, or potential naiveties by a first-time director”, he now looks at it and sees “radicalism in the writing. Radicalism in the research. Radicalism in the casting and the shooting. Radicalism everywhere. I am developing a much greater respect for it and, frankly, if that’s what I come away from this with, that’s akin to a love for my dad, isn’t it?”

Gary Carpenter, the associate musical director on The Wicker Man, says the film was subversive for its time because it reversed the prevailing trope “that a character – always a woman – who enjoys sex comes to a sticky end, whilst in The Wicker Man, being a bloke and doggedly holding on to your virginity leads to death.”

Sergeant Howie “had this wonderful f*** on his hands,” Shaffer told me bluntly, referring to Britt Ekland’s beguiling character, Willow MacGregor, “and had he taken it, he wouldn’t have been murdered”.

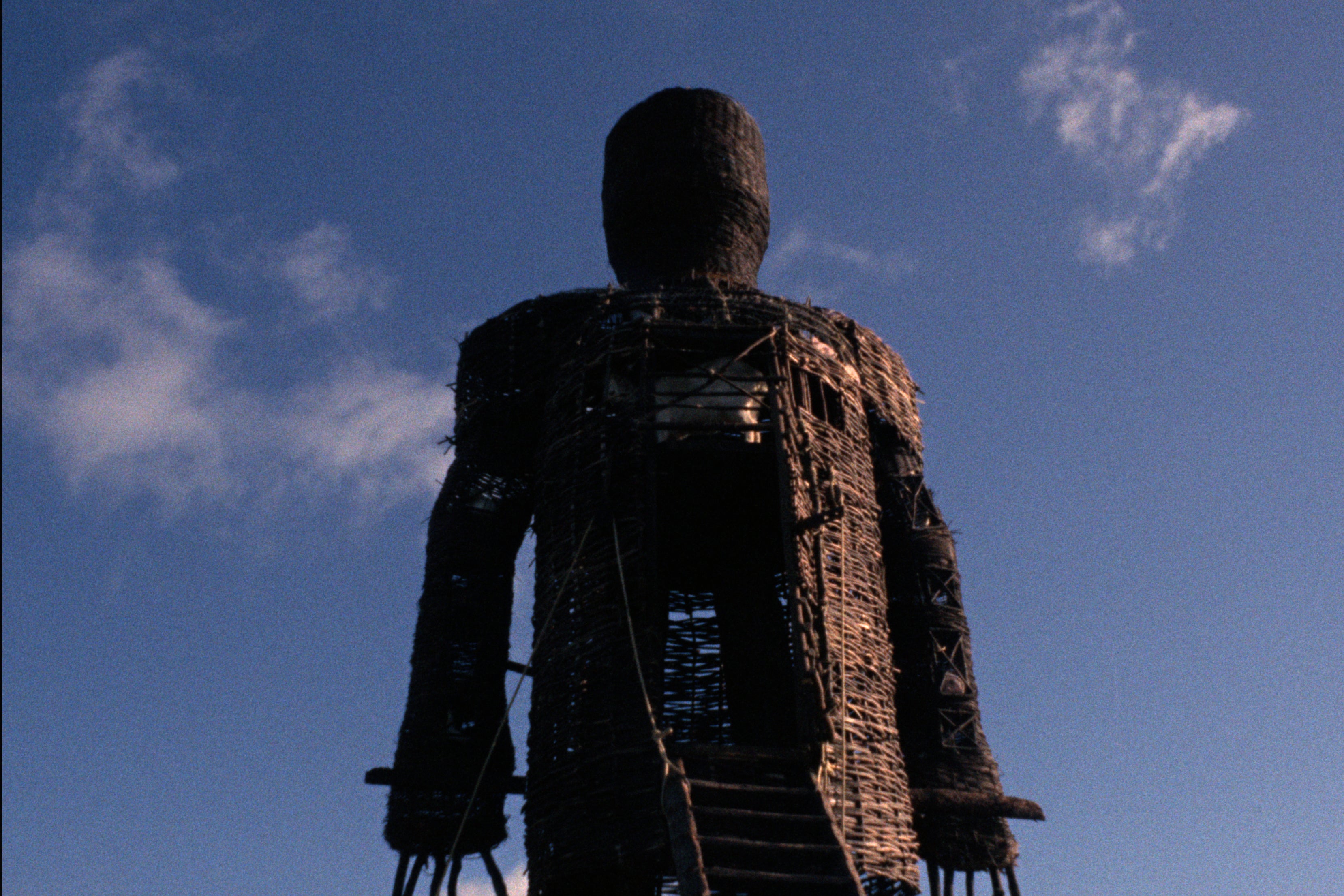

That he ends up being burned alive while the swaying inhabitants of Summerisle merrily sing “Sumer Is A-Cumen In” – one of cinema’s most chilling climaxes – left the sales team of British Lion’s new boss, Michael Deeley, speechless.

“They’d done nothing for the last 20 years except sell films like On the Buses or the Carry Ons,” said Shaffer. “When the lights went up at a screening we’d arranged for them, it was as if stalactites were descending from the ceiling... utter shock. I said, ‘I love this reaction.’ They simply couldn’t believe that the hero was allowed to die in the end. Where was the cavalry? They had no idea how to sell the film and it was buried.”

Shaffer made it clear that Paul Giovanni’s songs would play an important narrative role in creating the world of Summerisle by detailing the island’s traditions and beliefs. “Nevertheless,” says Carpenter, who appears onscreen with the same band that recorded the music, “I don’t think any of us expected it to be a cross between Witchfinder General and Brigadoon.”

It was stipulated that all of the music had to be for acoustic, portable instruments (an electric section during a chase near the end was “a small act of Hardy-targeted rebellion on Paul’s part”), and “upending expectations was crucial to the philosophy of the music – like the film”. A bassoon, for example, was used in the gorgeous “Willow’s Song”, sung by Willow as she tries to lure Howie into her bed, to “generate a weird and, in context, unusual sound” that was “disorientating”.

Carpenter is disappointed that the song has not been restored to its full length in the Final Cut, where it is shorter than in the Director’s Cut. “It’s butchered,” he says.

“The song is dramatically important as it builds in a way that tells you exactly what should have happened, or maybe does in their imaginations, between Willow and Howie.”

Famously, Ekland refused to let Hardy film her from behind from the waist down. He told me: “She said, ‘I don’t think you can shoot my bottom because I have a very bad bottom.’ Whether that’s true or not I don’t know, but that was her view.”

What happened next depends on who you talk to. Carpenter says an actress called Lorraine Peters was used as Ekland’s stand in, ostensibly without Ekland’s knowledge. Hardy, on the other hand, claimed that they rushed to Glasgow and hired a stripper.

Justin can’t help: the passing of time means that this particular slice of the film’s mythology is likely to remain forever hazy.

“We have done a series of interviews with people who were present at the time,” he says, “and all I can tell you is they all have a completely different memory of that story.”

Mackie getting to sing on the film was part of the chaotic way that The Wicker Man came together and people “mucked in”. She even found herself roped into teaching Ekland how to speak with a Scottish accent. She was probably never going to succeed in a day, and Ekland was ultimately dubbed by the Scottish jazz singer Annie Ross, “who had quite a mature voice for someone Britt’s age,” says Mackie.

Looking back, she wonders why they didn’t just let her use her own accent: “It would be so Wicker.”

Robin Hardy died in 2016, but his work endures. Overman has already written the pilot and a bible (an outline of the plot, characters, themes, etc) for his Wicker Man series, which will be set over a thousand miles away from the location of the film, in the Pyrenees.

He remembers seeing The Wicker Man for the first time when he was 13 – “way too young” – and being blown away by “the moment when you realise, ‘oh shit, they’re going to burn him!’” He is going to keep the film’s iconographic wicker man – “You’d be mad not to,” he says – but it will be his own story.

He is fascinated by the frightening idea that Shaffer and Hardy presented of encountering people “who will do anything to you”.

Fifty years later, it still “resonates with extreme religions in the real world”, he says. “You go and live in an ISIS caliphate and it’s probably a very similar thing, where you can’t reason with these people. You can’t persuade them.

“That idea that we can be subject to those sort of random things really speaks to something terrifying within us, I think.”

Doing The Wicker Man as an episodic ensemble piece will give him a “broader canvas” on which to have and go deeper into multiple characters who are “influenced by ideas of belief, sacrifice, ritual, change, fear”.

And whereas the film took place on an island where the previous year’s crops had died (hence the need for a sacrifice), his series will be set in a town that is dying.

There are places in the Pyrenees, Overman says, where the population has dropped from 50,000 to 5,000 in the last 30 years, and houses have lain empty and unchanged since the day their owners left or died.

“The Wicker Man had a powerful sense of place and I want this to really take you into a world that isn’t familiar to you and is strange.

“So to make it feel more modern, it’s about people being drawn away to the big city, the lure of technology and all those sort of things, and this community that feels that it’s not their crops that are dying, but they are dying.”

He knows that there will be some people who won’t like him calling his series The Wicker Man. However, he hopes that they will see that he is being respectful to the film by not copying it and hanging something original on its themes.

Whatever the outcome, it will help to ensure that interest in The Wicker Man lives on.

The 50th anniversary 4K ‘The Wicker Man’ restoration will return to cinemas nationwide on 21 June. A 5-disc Collector’s Edition will be available to own from 4 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments