How the power of language – and the weird world of JD Vance – could derail Trump

Only Donald Trump could have fallen for his vice presidential pick’s personal history, writes Robert McCrum. And while the former president has fallen strangely quiet, Kamala Harris’s happy warrior Tim Walz wants to bring it on

America is a great country whose troubles distress us greatly. We watch in fascination as our American cousins enact the rituals of an extraordinary society that’s been made and remade through the language of its people in the everyday traffic of a vigorous democratic argument.

And 2024 has been a vintage year for this spectacle. Strange though it might seem, almost none of what we’re seeing today is actually so new or surprising, but more a case of business as usual in the great republic.

When the men – it was exclusively men, many of them lawyers – first invented their country in 1776, they wrote as the children of the Enlightenment. The “truths” laid before their people in the Declaration of Independence were, said Thomas Jefferson, “self-evident”. The United States has conducted its democratic experiment according to such “truths” ever since.

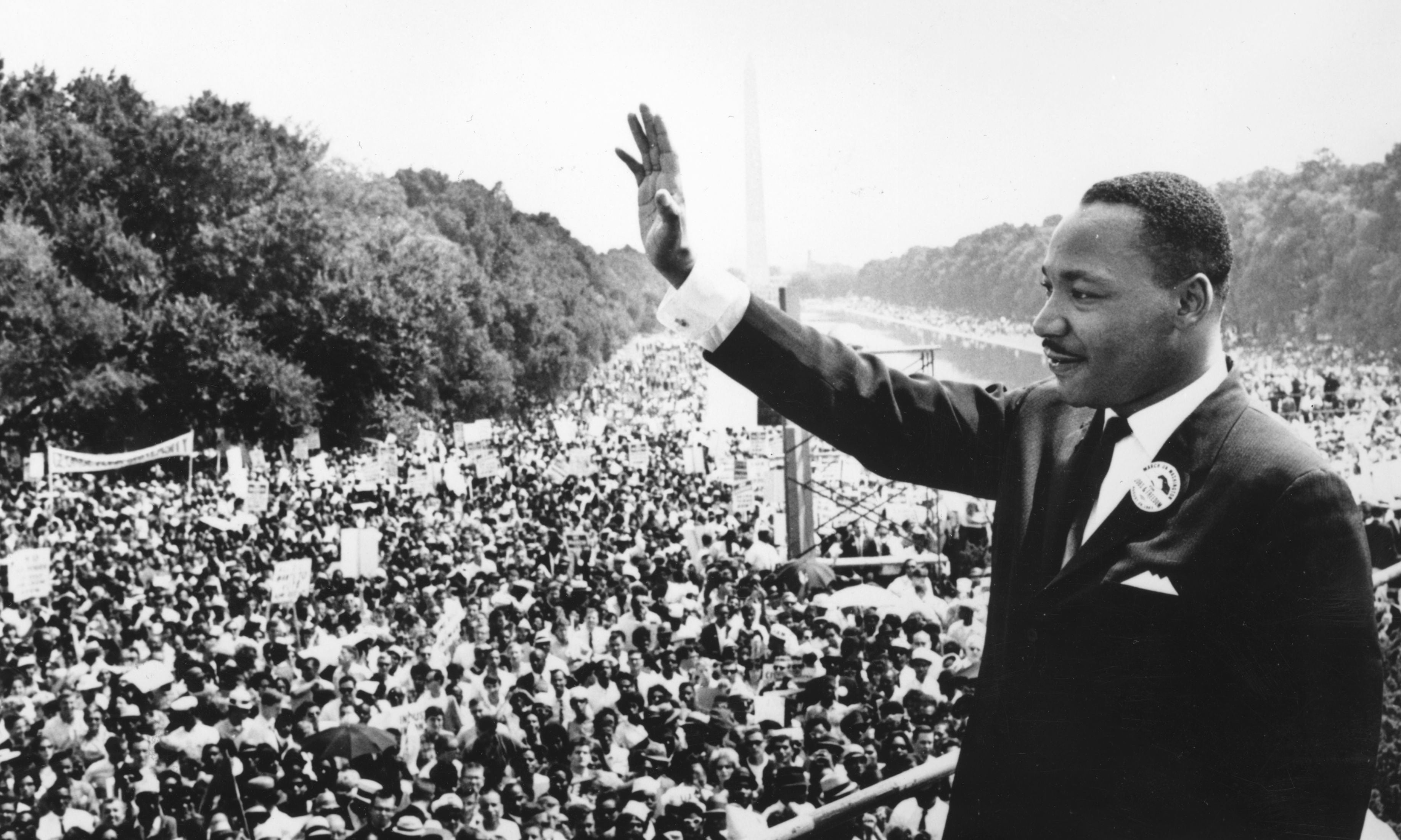

High noon in Philadelphia was a heady moment. American political rhetoric has lately become shrill, thin, bitter, and all-round depressing. At its height, however, the voice of “we, the people” has been thrilling. It was Jefferson’s clarity to which the great US speech-makers harked back. “I have a dream,” declared Martin Luther King Jr, braiding his appeal with the cadences of the Bible.

When Lincoln intoned: “Four score and seven years ago… a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal…” he was appealing to the good sense of a people confused by civil war. Since Gettysburg, Americans have come to expect their presidents to inspire.

FDR, memorably, pronounced that their only fear was “fear itself”. Subsequently, Kennedy picked up this torch with: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.”

Historic words, which smell of the lamp, but uttered in a spirit which lingered with Obama when, in 2008, he proclaimed “a more perfect union”, in his celebrated speech asking Americans to band together.

Fast-forward to that nadir of American politics, the disputed ballot of 2020, and the 6 January 2021 assault on the Capitol. The worst of the Trump years has been the relentless intimidation of America’s self-evident “truths”.

Under the aegis of a corrupt and narcissistic clown-cum-felon every truth has been inverted. News is fake. Climate change is a hoax, Covid a scam. In the teeth of contrary evidence, an election was “stolen”, etc, etc. No question, the New World’s mantra of life, liberty and pursuit of happiness has been driven to distraction during the years 2016-2024.

History teaches that there will always be a reckoning. Now, finally, we are perhaps beginning to witness a belated return to candour, serenity and reason. The latest sad fakery perpetrated by Trump has been the nomination of JD Vance as his running-mate for the presidency. Only a demagogue who – it is said – never reads could make such an astounding misstep. But it has, inadvertently, broken the spell.

Forget the hype and the movie, the extravagant praise (“Yale graduate writes redneck classic”) and the breathless transatlantic acclaim. Hillbilly Elegy, “a memoir of a family and a culture in crisis”, is a cynical, near-fraudulent self-presentation by a politician on the make.

First of all, before we get to Vance himself, there’s the small matter of his origins. Or rather his grandmother’s origins in Jackson, Kentucky. This modest town is important to our hero because of its people. “The millions of working-class white Americans of Scots-Irish descent who have no college degree” are the “folks” Vance longs to identify with.

“Americans”, he writes, “call them hillbillies, rednecks or white trash. I call them neighbours, friends and family.” Vance’s problem – never fully interrogated by the critics who made the book a bestseller – is that they’re not really neighbours. Vance grew up in Middletown, Ohio, which is many miles northwest of Appalachia.

I have travelled in Appalachia and spent time with these “hillbillies” who speak a traditional American English – afeared, damnedest, plum right – that is often mistakenly said to be a relic of Elizabethan English. They are a dignified community with a fierce pride in their isolated heritage.

I remember Willard Watson, an old-time storyteller in the Appalachian hills, who used to distil “moonshine whiskey” the traditional way, next to a stream. A pint of his “mountain lightning” was a revelation. Watson pronounced pint as “parnt”, in these sublime words of American English: “A pint [of whiskey] is enough, and a pint is just about too much… You drink a pint of moonshine whiskey, and you won’t know where the sun went down or where it come up. Get you where you couldn’t hit the wall with a handful of beans.”

Here’s an Appalachia old-timer whom Vance – reinventing himself and wanting to outgrow his working-class roots – has no interest in, or knowledge of. Only Trump, for whom image and bravado are everything, could have fallen for this kind of fabrication.

Trump’s preferment of Vance also betrays his deep contempt for the historic role of his running mate. In selecting a “mini-me” he may have made a strategic error in the battle for self-evident truths.

Up to this moment, the Democrats’ faltering campaign had been bedevilled by Trump’s Teflon qualities: nothing sticks. Day is night. East is west. Truth is false, red is blue, corruption is the state’s trade, and vice versa. But then, history stepped in.

Enter the little-known governor of Minnesota, Tim Walz, the Midwest middle-American who, raised in remote Nebraska, is JD Vance’s twin in roots, but not in mood.

Where Trump’s running mate, with his “childless cat ladies”, is a miserabilist suited to the candidate who never smiles, Walz is the kind of character Americans describe as “a happy warrior”, a fighter who’s an optimist, a regular guy who’s at home in his skin.

As soon as he joined Kamala Harris’s campaign, thanking the Democrat underdog for “giving back the joy” to the election, Walz was trading in some vintage self-evident truths. Indeed, Walz had already, single-handed, transformed the race for the White House not with a speech, but with one heartfelt Anglo-American adjective: “weird”.

Walz did not know it, but he had just hit the jackpot. Deep in the dark word-hoard of our language, “weird” is a semi-untranslatable adjective replete with dread, mystery and menace. As a noun, “weirdo” conjures a range of personalities, none of them reassuring in ways we cannot quite explain. Weird is a word we hold in our bones. Walz used it on MSNBC’s Morning Joe to describe how Trump and Vance “creeped me out”. Having plucked weird from his unconscious, he soon discovered that it was the mot juste.

No surprise that it caught on. From Old English – and weird is nothing if not Anglo-Saxon – you get an energy that seems to stem from witchcraft. You can generalise it to describe something unusual, but its older meanings are more specific, and more potent. Weird derives from the Old English noun “wyrd”, essentially meaning “fate”.

By the eighth century, the plural “wyrde” had begun to appear in texts as a gloss for the Latin name for the Fates – the three goddesses. Shakespeare adopted this usage in Macbeth, in which the “weird sisters” are presented as three witches. The later adjectival use of weird developed from Shakespeare’s reinterpretation of the word.

Who knows? Weird may turn out to be the game changer. Few American dads could be more un-weird than Walz. (That’s the point: he is everyperson, who speaks our language. In a society made of words, this is priceless.) You could stand in line at Walmart behind Governor Walz and not give him a second glance, though you might also find yourself engaged in a conversation about the weather, or the game, or the state we’re in. In US election parlance, Walz is profoundly “relatable”.

This “what-you-see-is-what-you-get” son of the soil has served in the US military, been a devoted schoolteacher, excelled as a football coach, loves to hunt and shoot, adores his wife and kids, served six terms in Congress, and has the confidence to declare that: “People like JD Vance know nothing about small town America.”

Better still, from a Democrat point of view, Walz has no time for Trump, and expresses his opposition in the simple, accessible language of self-evident truths. “You can’t even go to a Thanksgiving party now because you’ll end up in some weird fight… These guys are just weird.”

To Walz, this yields a simple political dividend: “This is not what middle America is… I can’t wait to debate the guy [Vance].”

Trump, meanwhile, has fallen strangely quiet, unable to fathom being “weird”. Harris’s happy warrior, by contrast, wants to bring it on.

“Fight and win” is language Americans understand. On the night Walz first met his supporters in Philadelphia, his message had a clarity Washington, if not Jefferson, would have saluted: “We’ve got 91 days. My God, that’s easy. We’ll sleep when we’re dead.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments