‘Utterly reckless’: Why we need a ban on deep sea mining

Supporters say it’s crucial for the move towards renewable energy. Scientists, activists and even Google argue it should be banned until we can fully understand the impact it could have on the oceans, marine life and the rest of the world. Charlie Jaay dives into the deep sea mining debate

The deep sea includes all water below 200m, which is an area covering approximately 60 per cent of our planet. Although the most common ecosystem on Earth, it remains one of the least explored and understood. It is an environment of extremes but, thanks to recent technological advances, scientists have found the deep ocean not to be devoid of life, as once believed, but home to myriad life forms.

Even at depths of more than 5,000m, there are many endemic, unique and highly evolved species that are able to survive and flourish, with new species routinely being discovered. One of the deepest living animals is a sea cucumber found at a depth of over 10,000m, while a distant relative to the cod, a deep sea brotula, has been discovered 8,000m below the ocean surface.

Dr Diva Amon, a deep sea biologist, says: “The deep ocean is a vast reservoir of biodiversity. From glowing sharks and 11,000-year-old sponges to Dumbo octopus and blind white crabs that farm bacteria on their hairy chests. Deep sea species are not only weird and wonderful, they have challenged our very understanding of how life can thrive.

“Although seemingly far removed from us, they are inextricably linked to our survival by providing essential functions and services, and could provide solutions to the greatest challenges facing humankind in the future”, she says.

Research shows the deep sea is crucial to our lives, carrying out vital global functions, which affect us in many ways. Nutrient regeneration is necessary for fuelling surface productivity and nurturing fish stocks. Various habitats also host life forms such as sponges and bacteria that are sources of new antibiotics and other medicines.

In a climate and nature emergency, when the health of our oceans is at the brink and we are already seeing widespread and fundamental changes happening in the ocean, there is absolutely no place for opening up to deep sea mining

In addition to providing around 1 billion people with their main source of protein, our oceans produce more than 50 per cent of the planet’s oxygen and absorb more than 60 per cent of our carbon emissions. Because carbon dioxide is denser than seawater, it sinks to the ocean floor, making it our planet’s largest reservoir of stored carbon, vital in helping to tackle the climate crisis.

However, this fragile ecosystem is facing more threats now than at any other time in history. Commercial fishing, plastic pollution, drilling and global warming all take their toll on marine life, but the abundance of metal-rich mineral deposits in the deep ocean seabed means there is now a new direction in ocean exploitation, with a number of countries and companies showing an interest in mining these areas.

There are three types of deep sea habitats where metal-rich mineral deposits are formed, and mining could take place.

The first are abyssal plains. These vast, flat, sediment-covered areas of the deep ocean floor are formed by thick blankets of sediments, accumulating over hundreds of thousands of years. Although in constant darkness, many species live here, including the deepest-dwelling octopus.

Polymetallic nodules are found on these abyssal plains. These potato-sized rocks contain high concentrations of manganese, iron, nickel, copper, titanium and cobalt, while supporting a vast range of suspension feeders and sediment communities. They take millions of years to fully form, and are the most abundant and widely distributed of the major ores currently pursued by mining companies, which plan to suck them up from the seabed.

The most extensive deposits of nodules are located at a depth of 4,000 to 6,000m, in an area which many scientists believe could be one of the most biodiverse of the deep sea, called the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone. This area of the Pacific Ocean lies between the Hawaiian Islands and Mexico, and contains deposits of cobalt, nickel and manganese which amount to more than the total known land-based reserves. Nineteen exploration contracts have been awarded for polymetallic nodules.

The next is seamounts. These underwater mountains rising 1,000m or more from the seabed are regarded as hotspots of ocean biodiversity and support a huge variety of life. Many are in remote surroundings and studies continually find previously unknown species.

Cobalt crusts grow on the exposed sides of seamounts, and are found throughout the world’s oceans, at depths of 400-4,000m. In addition to cobalt, they are also rich in other essential metals and several rare Earth elements. These crusts would be stripped from seamounts if deep sea mining were to take place. Some estimates suggest the total surface area of cobalt crusts contain approximately 1 billion tons of cobalt.

The Western Pacific has been designated as the Prime Crust Zone, and is thought to contain over 7 billion tons of crust. The oldest found here is approximately 160 million years old.

The last is hydrothermal vents. These form due to volcanic activity heating fluids below the ocean floor, which emerge as underwater geysers and hot springs. They are typically rich in sulphides of heavy metals such as copper, zinc, iron and lead. A new kind of ecosystem has been found around these vents, based on hydrogen sulphide, normally toxic to animals. Since 1977, when the first deep-sea vent was discovered, scientists have identified over 500 species of animals new to science, specific to this environment. Plans for mining at vents are most advanced in the Western Pacific, and would involve machines on the seabed, scraping and pulverising the mineral deposits at a vent field.

The “lost city” field of hydrothermal vents consists of hundreds of white spires 30-200 feet tall, giving off hot alkaline fluid and supporting trillions of uniquely adapted microbes, but is now part of a mining exploration contract issued by The International Seabed Authority (ISA).

Founded in 1994, the ISA is an intergovernmental organisation, mandated by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, to organise and regulate deep sea mining activities in all marine areas outside national jurisdiction. These areas are known as the high seas, which make up almost two-thirds of the world’s ocean.

It also has the responsibility of ensuring effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects that may arise from such activities. It currently has regulations in place which set rules for prospecting and exploration and, so far, has awarded 31 exploration contracts, each lasting 15 years, covering an area of over 1 million square kilometres of the deep sea bed of the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans. It has never yet turned down a licence application.

Its member states have, since 2014, been negotiating regulations for extraction of the minerals from the seafloor. Once these regulations and various other plans are adopted by the ISA, the first seabed mineral exploitation contracts beyond national jurisdiction can be applied for.

Its dual mandate of approving contracts for exploration, for which it receives substantial application fees, while being responsible for the seabed, has given rise to questions over the ISA’s effectiveness as a regulator, and claims of bias towards resource extraction rather than the health of the ocean. The ISA has also been widely criticised for its environmental impact assessment (EIA) process. These EIAs are carried out by the mining companies themselves, and not independently verified. They are also not shared with the governments who are deciding whether to grant a permit.

There is a real political question of credibility for the UK government on the environment. It is trying to position itself as a global ocean leader and champion of the environment, but how is this compatible with getting involved in an incredibly risky industry

Although regulations are currently still in the exploration phase, they were expected to be finalised last year, by the ISA, meaning deep sea mining could then begin if governments gave the go ahead, but negotiations were delayed due to Covid-19. However, last month, the Pacific Island state of Nauru activated a clause in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, known as the “two year rule”, designed to pressure the ISA to adopt regulations in two years, or grant a mining contract in two years even without regulations being in place.

According to Duncan Currie, an international lawyer who has been attending ISA for 12 years, there are several problems concerning the exploitation regulations.

“A key problem is that once exploitation contracts are awarded, they will be in place for at least 30 years and will be very difficult or impossible to stop, if and when practical experience shows they are causing unacceptable damage. In fact they are almost indefinite, as current draft regulations provide for multiple 10-year renewal periods. So unlike fisheries, where catch limits can be changed and measures introduced to control fishing effects at any time, the regulations would be in effect set in stone,” he says.

“There is also a real danger that one or two contractors, through their sponsoring state, pressure the ISA to ram through inappropriate and ineffective regulations within a few years. This is very concerning, as it is likely to trigger a race to the bottom, as other contractors would not want to be left behind, and because it risks rushing what needs to be a carefully considered process.

“The regulations are far from being in a form that can be adopted, yet standards are being developed based on those inadequate regulations drafted over two years ago. This putting the cart in front of the horse illustrates the fundamental underlying problems with the industry pressing for rapid adoption of rules and standards to allow them to start mining in a couple of years, when the science and technology is in its infancy,” he explains.

Currently, only a few governments are expressing interest in involvement with deep sea mining, and are sponsoring exploration: the UK, France, Germany, Belgium, China and a small number of Pacific Island states.

The British government sponsors some of the largest areas of exploration through its two contracts in the Pacific Ocean with UK Seabed Resources Limited (UKSRL), a subsidiary of Lockheed Martin, one of the biggest weapons companies in the world. There are estimates that deep sea mining could be worth up to £40bn to the UK economy over the next 30 years. Although signed in 2013 and 2016, these contracts have only recently been released, leading Greenpeace to claim they are “error-ridden” and “possibly unlawful”, and launch legal action against the British government over its lack of transparency.

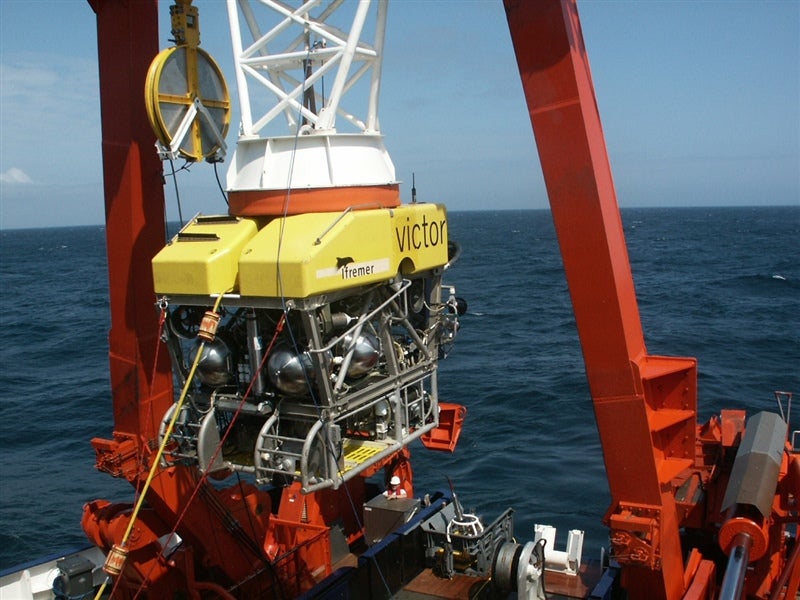

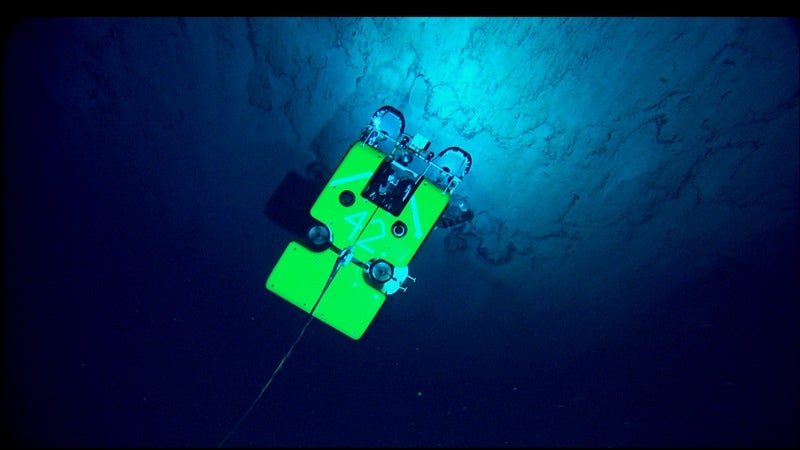

The three largest corporations involved with deep sea mining are UKSRL, Canadian company DeepGreen and Belgian company Global Sea Mineral Resources, whose 25-tonne robot became stranded at a depth of more than 4km on the Pacific Ocean seabed earlier this year due to a broken cable. They have all been pushing hard, calling on governments to speed up and finalise rules to allow extraction.

A common claim by those interested in mining the deep seabed is it is getting much harder to obtain the metals we need for our move away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy technology, but these can be found in sufficient quantities in the ocean. DeepGreen, now part of a merger and known as The Metals Company, along with other corporations involved in exploration of the seabed, also claim deep sea mining creates minimum or no adverse impact.

However, these claims have both been disputed.

The Institute for Sustainable Futures’ report, titled “Renewable Energy and Deep Sea Mining: Supply, Demand and Scenarios”, concludes that even if there were to be a 100 per cent renewable energy economy globally by 2050, it would not be necessary to mine the deep sea.

Although there is a lack of long-term studies concerning potential effects, one of the longest, taking place at depths of 4,000m in the Pacific, found machinery tracks to still be clearly visible after 26 years.

Research also suggests, while potential impacts vary depending on the type of resource, marine life hundreds of kilometres away from the mining site could be affected by mud and chemical dispersal resulting from the extraction, arguing that significant risks are also posed to midwater ecosystems.

A clear parallel has also been drawn between deep sea mining and trawling, and carbon emissions. According to a report earlier this year, fishing boats trawling the ocean floor release carbon emissions equivalent to the entire pre-pandemic global aviation industry. These scientists also recognised deep sea mining to be a similar threat but, could not quantify the expected emissions from this.

Although not yet understood, the cumulative impacts of these deep sea mining operations are likely to be long-standing, and felt ocean-wide.

Helen Scales, a marine biologist and author of The Brilliant Abyss, says: “All three targets for deep sea mining – seamounts, hydrothermal vents and abyssal nodules – are habitats for countless unique species, from scaly foot snails with their strange iron-clad shells to nodule-dwelling tardigrades and corals that grow for thousands of years. Mining would destroy those habitats and species, plus so many more that remain unknown to science.

“Impacts would go beyond the seafloor, with sediments stirred into the water column, threatening to smother and choke multitudes of midwater organisms. It would matter not just for those lost populations and species but the roles they collectively play in the global ocean ecosystem that helps to keep the rest of the planet healthy and habitable,” she says.

It also feels utterly reckless to be disturbing the bottom of the seabed, when we still need to do a lot of scientific research to fully understand how the ocean’s carbon store functions

There are also concerns over who will be watchdog, at depths of a few thousand metres below sea level, and what will happen if any problems occur. Also unknown are the effects noise and light pollution from the industrial machinery would have on whales and other cetaceans, and the unique organisms living in the dark depths of the ocean, which have adapted to almost total darkness.

Deep sea mining advocates claim the process is necessary for renewable energy technologies, but there is growing resistance to the industry. No company involved in this sector has yet expressed interest, and many have even spoken out against it. BMW, Volvo, Google and Samsung have joined governments, scientists, NGOs, the fishing industry and others in growing calls for a global moratorium on all deep seabed mining activities, which, they say, is the only responsible way forward until all risks are understood, all alternatives are explored, and no loss of marine biodiversity, or degradation of marine ecosystems, can be ensured. The European parliament has also called on the Commission and EU member states to promote a moratorium.

The first attempt at deep sea mining took place in Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) Bismarck Sea. The Solwara 1 project planned to extract copper and gold from hydrothermal vents, but failed, after Nautilus Minerals went into administration in 2019, leaving the PNG government, which had a 30 per cent stake in the business, owing $157m. This led the PNG government and civic societies in the country, along with the Pacific Island state governments of Fiji and Vanuatu, to call for a moratorium. Damage caused to the ocean by seabed mining also has the very real potential of affecting tuna fisheries, on which Pacific states are heavily dependent.

Louisa Casson, oceans campaigner at Greenpeace UK, says: “We need to draw a line, and keep the deep sea off limits.

“In a climate and nature emergency, when the health of our oceans is at the brink and we are already seeing widespread and fundamental changes happening in the ocean, there is absolutely no place for opening up to deep sea mining. We shouldn’t even be considering it – it’s simply too dangerous.

“It also feels utterly reckless to be disturbing the bottom of the seabed, when we still need to do a lot of scientific research to fully understand how the ocean’s carbon store functions. We don’t know what that disturbance could lead to, or how widespread the disruption could be.

“So, in addition to a Global Ocean Treaty to raise the standards, and put certain areas off limits to all activity, we need a ban, or at least a moratorium, on deep sea mining,” she says.

“Greenpeace and other groups have repeatedly written to the UK government and ministers, calling for them to support a moratorium, but so far our government has refused.

“There is a real political question of credibility for the UK government on the environment. It is trying to position itself as a global ocean leader and champion of the environment, but how is this compatible with getting involved in an incredibly risky industry, which scientists are already saying will lead to irreversible and unavoidable harm to the oceans”, she adds.

Currently only 1 per cent of the high seas are protected from all industrial activities, and it is looking increasingly likely that the wonders of the deep ocean could be destroyed before even being discovered. This has led to calls for a new Global Ocean Treaty, to be agreed at the UN, which would create marine protected areas across the high seas, and set standards for environmental impact assessments, so the most destructive activities, such as deep sea mining, aren’t permitted even outside of protected areas.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments