The writer declared dead on his 21st birthday – who then led a most extraordinary life

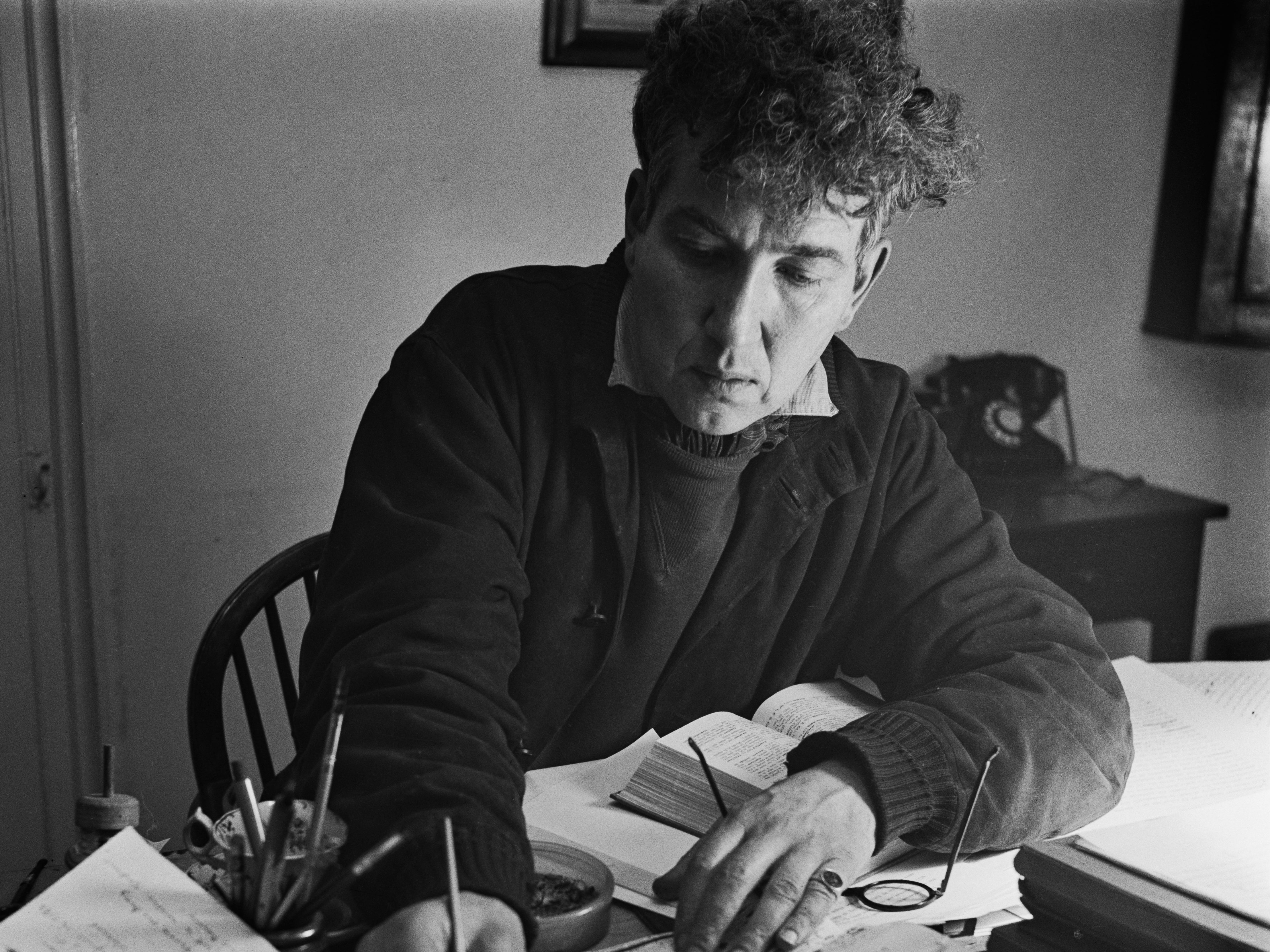

Robert Graves was never quite able to fully say goodbye to all that, writes James Rampton

On 20 July 1916, in the thick of the Battle of the Somme – one of the bloodiest conflicts in the whole of the First World War – a German shell exploded next to Robert Graves. At that moment, he wrote: “I felt as though I had been punched rather hard between the shoulder blades.”

Graves, who had enlisted two weeks after the war broke out and attained the rank of captain at just 20 years of age, sustained multiple life-threatening injuries, including one from a fragment of shrapnel that tore through his lungs.

The writer was so severely wounded that on his 21st birthday, 24 July 1916, he was declared dead at a dressing station close to Mametz Wood. His mother was even sent a telegram informing her that he had passed away, and his death was announced in The Times.

Miraculously, Graves survived and went on to lead the most extraordinary life for the next 69 years. The writer, who was already receiving acclaim for his compelling poetry about life on the Western Front, was sent to recuperate at Craiglockhart, a military hospital in Edinburgh.

His fellow war poets and friends Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen were also being treated there. Graves was diagnosed with shell shock, which we would now categorise as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Acknowledging the impossibility of returning to the frontline, Graves accepted the severity of the trauma he was experiencing. He later wrote: “I thought of going back to France, but realised the absurdity of the notion.

“Since 1916, the fear of gas obsessed me: any unusual smell, even a sudden strong scent of flowers in a garden, was enough to send me trembling. And I couldn’t face the sound of heavy shelling now; the noise of a car back-firing would send me flat on my face, or running for cover.”

Graves, who went on to become one of the most highly regarded writers of his generation, responsible for such unforgettable works as his autobiography Goodbye to All That and his books, I, Claudius, Claudius the God and The White Goddess, was also assailed by memories of the idiocy of his army superiors.

William Nunez, the writer-director of The Laureate, a poignant new film about Graves, says: “He got to experience the folly of the upper command. He kept imploring the generals not to shoot poison gas canisters towards the enemy. And then sure enough, they shot them – and the wind blew the poison gas right back towards them.”

Graves also felt like an outsider in the very “laddish” British army, Nunez says. “He was very puritanical because he was brought up under his mother’s reign of fear. Then he went straight from Charterhouse school into the army.

“He had the fortune or misfortune to have a German mother and an Irish father as well. He had ‘von Ranke’ as his middle names. So that never sat well with either his classmates or the people serving under him in the army.”

The director continues that Graves’s sense of being ostracised “helped solidify him as a disrupter, an outlier. He always marched to his own drum, even in his later books, like King Jesus and Count Belisarius. His ideas were so out there.”

But Graves’s mental torment lingered. It did not just live with him in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of the Somme; it disturbed him right up until his death in 1985. He once said: “Since the end of the war, I have been plagued by recurring daydreams of war. They persist like an alternate life.”

England looked strange to us returned soldiers. We could not understand the war-madness that ran wild everywhere, looking for a pseudo-military outlet

And yet his experiences during the First World War are merely the beginning of a life story that defies belief.

On top of his PTSD, Graves felt a strong sense of alienation when he tried to re-enter domestic life. As he put it: “England looked strange to us returned soldiers. We could not understand the war-madness that ran wild everywhere, looking for a pseudo-military outlet. The civilians talked a foreign language; and it was newspaper language. I found serious conversation with my parents all but impossible.”

However, after the war, Graves (portrayed in the film by Tom Hughes, best known as Prince Albert in Victoria) found his feet when he met Nancy Nicholson, a painter and feminist. They married in 1918 and rapidly had four children. They settled down far from the madding crowd in the appropriately named World’s End cottage in Islip, Oxfordshire.

Nicholson, who is played in The Laureate by Laura Haddock (White Lines), was no mere armchair feminist. For instance, she infuriated Graves’s very traditional parents by insisting that their children take her surname.

In addition, when birth control was still against the law, she cycled around Oxfordshire villages showing women how to use contraception.

At the outset, Graves and Nicholson enjoyed a loving, balanced relationship. Haddock says: “At first, she and Robert describe their relationship as a partnership of equals. She certainly sees herself as somebody who is as strong, as powerful and as important as the man that she is marrying.”

Despite their apparent domestic bliss, though, Graves was afflicted by a serious case of writer’s block brought on by his traumatic war experiences. Sometimes at night, he would be discovered running around the garden at World’s End, screaming in terror.

According to Nunez: “He couldn’t write because his PTSD would go on for days, or there would be sudden flashes. Anything could set him back – like the ringing of a telephone.

“When he was in London, he would walk down Piccadilly and, all of a sudden, he would see all the people walking by as dead on the pavement, and he would just freeze. It was very debilitating for him. He was very much inward-looking, and he needed something to clear the fog.”

The writer retreated more and more inside himself. While Nicholson earned money through her art, he took on the role of what we would now call “house husband”. The spark had gone out of their relationship, and the marriage was in crisis.

Graves admitted as much when he wrote: “My disabilities were many: I could not use a telephone, I felt sick every time I travelled by train, and to see more than two new people in a single day prevented me from sleeping. I felt ashamed of myself as a drag on Nancy.”

Nunez observes: “He was just becoming so dependent on his wife because he couldn’t write. He became the domesticated person in the household, instead of the writer. He had to care for the children while his wife was doing a lot of work illustrating books. So he needed a jolt – and sure enough, he got it.”

That jolt came in the form of the extremely forthright, sexually free American poet Laura Riding (played in the film by Dianna Agron from Glee), whom Graves, an admirer of her writing, invited to stay at World’s End in 1926.

Agron describes Riding as: “Absolutely fiery and absolutely possessed with this notion that if she believes it to be true, she should say it and she should do it.”

A veritable force of nature, Riding soon turned the couple’s lives upside down. Her vibrant presence helped Graves rediscover his muse.

She had an instant impact on his creativity. Nunez explains: “Laura was a breath of fresh air because she was a great editor. They were a real partnership in the early days. They wrote together, and so, of course, they were bouncing ideas off each other. I think that’s what Robert needed – that give and take with another writer. It sparked him into life again, and he finally realised, ‘I can write! I can do this on my own.’”

Riding’s influence certainly helped to unchain Graves’s artistic spirit. Nunez makes an interesting analogy. “I equate it to the John Lennon story. I think of Robert Graves as John Lennon. Graves was a successful poet, like John Lennon was a successful musician, with a wife and children, and then he meets this outlier artist, Laura Riding or, in Lennon’s case, Yoko Ono.

While Nancy admired Laura very much for the outspoken, progressive views that she brought with her, at the same time Laura figured out, ‘Boy, this neediness is tiresome’

“Everyone hates this other woman because she’s totally un-British. Then he makes the unpopular decision to go with her, and yet he becomes a different artist. I don’t think one is better than the other. Some people love the early John Lennon in The Beatles, and some people love his solo work.”

The director carries on: “It’s the same thing with Robert Graves. After he met Laura Riding, he became a different writer. His mind was expanded and his imagination was enhanced. Because of Laura, he was then able to write The White Goddess and other things like that.”

Riding did not just have an effect on Graves’s writing, though; she upended his entire existence. Determined to liberate the couple from their repressed, stiff-upper-lip upbringing, the American first seduced Nicholson. Then, with his wife’s blessing, she embarked on an uninhibited sexual relationship with Graves.

At first, their ménage à trois – which they dubbed “the Trinity” – proved a great success. In The Laureate, Nicholson declares: “This meeting of minds and bodies proved it was possible for three people to sustain a modern relationship without any regards to the formal conventions of society. I can’t deny my happiness as we basked in the glow of our Trinity.”

But – and didn’t you just know there was going to be a “but”? – their happiness was short-lived. As Graves began to worship Riding as a goddess, Nicholson felt more and more shut out of their love triangle. In the film, she laments: “If you invite a serpent into your home, perhaps you shouldn’t be surprised if it bites you.”

Graves abandoned his wife and four children at World’s End, and set up home in Hammersmith, west London, with Riding. Sanctimonious eyebrows were raised when they started throwing wild parties and throwing out even wilder ideas.

The writer then issued another invitation that was to have a cataclysmic effect on his life. Impressed by the verse of the young Irish poet Geoffrey Phibbs, Graves asked him to come and stay with them in Hammersmith.

The trio set up a new printing company. Keen to be seen as iconoclastic, they arrogantly suggested burning the work of TS Eliot and Ezra Pound. They called themselves “The Holy Circle” and were dedicated to revering Riding.

Perhaps inevitably, the circle soon began to fracture, as Graves initiated an affair with his secretary at the same time as Riding started sleeping with Phibbs, who was already married to the painter Norah McGuinness. Then, if you can believe it, Phibbs and Nicholson embarked on a relationship – do keep up!

Nunez outlines the reasons why this damaged quartet leapt so eagerly onto this dizzying sexual merry-go-round. “Nancy was able to relinquish the role of Robert’s carer because Laura was willing to take over the role of facilitator for him. I think that gave Nancy a great sense of relief.

“While Nancy admired Laura very much for the outspoken, progressive views that she brought with her, at the same time Laura figured out, ‘Boy, this neediness is tiresome’. This relationship where the man is always demanding, ‘Read my poem. What do you think of it? Oh, I have PTSD today’ – it does wear you down. That’s why Riding decided to go off and find a fourth member of the group, Geoffrey Phibbs.”

Unsurprisingly, this exhausting sexual carousel proved unsustainable. As the circle fell apart and Graves and Phibbs argued over Riding, she took drastic action.

On 27 April 1929, she attempted suicide by hurling herself out of the fourth-floor window of their house and seriously injured herself. Distraught, Graves jumped after her – albeit from a lower floor. But amazingly, he emerged unscathed.

The incident scandalised society and Graves was even charged with attempted murder. Desperate to escape from stifling, judgemental British society, later in 1929 the couple moved to Deia in Majorca.

The same year, Graves wrote Goodbye to All That, one of over 140 books that he penned during a prolific career. Many of them are still in print and on the school curriculum.

Graves split from Riding in 1940 and, after finally divorcing Nicholson in 1949, married Beryl Hodge, the former wife of a co-writer, in 1950. With Hodge, he fathered four more children. This did not stop him having alleged affairs with various young “muses”.

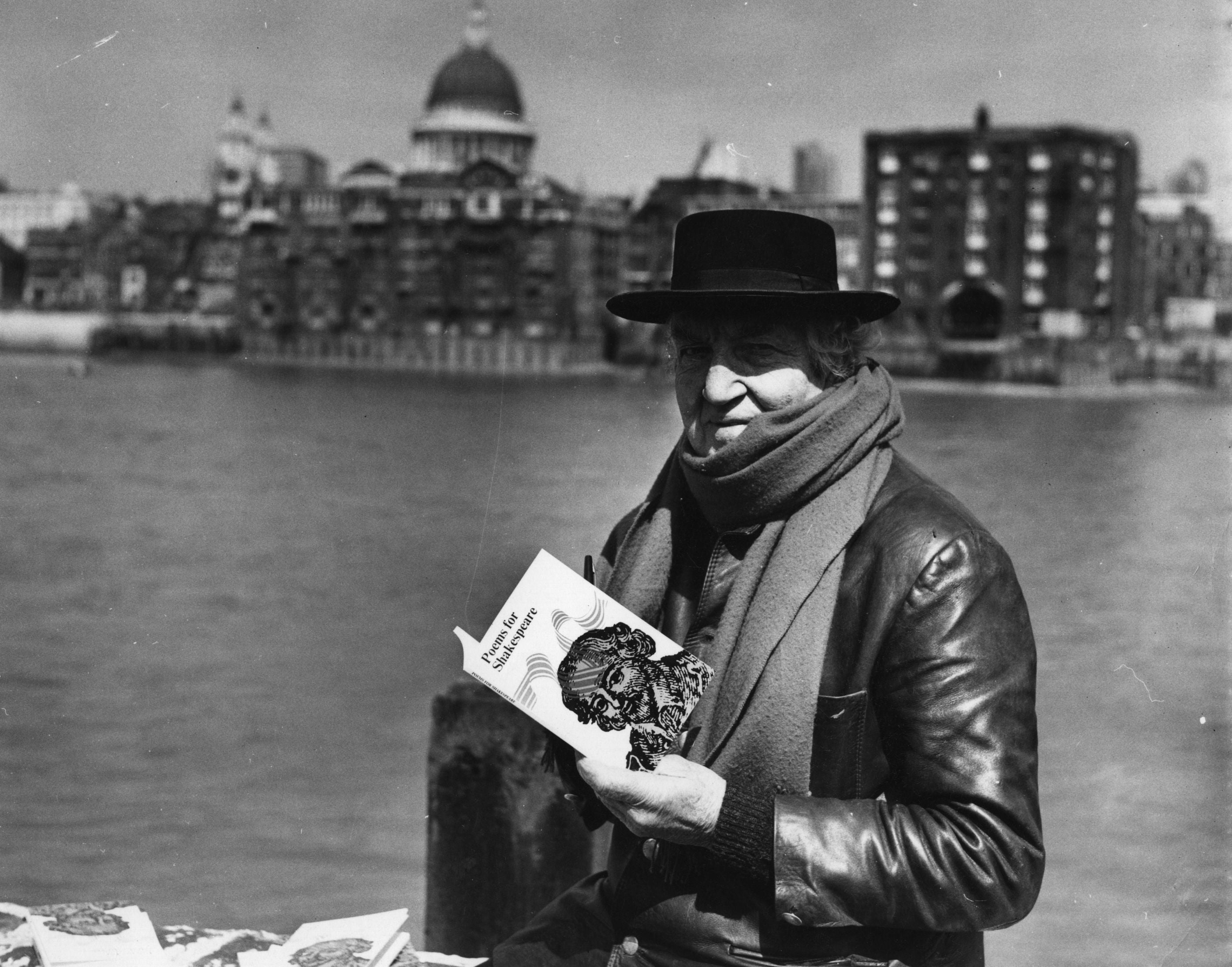

Eventually, Graves managed to ride out the storm that his turbulent private life had whipped up and achieve respectability. In 1961, he was made professor of poetry at Oxford University.

Seven years later, Graves was given the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry by Queen Elizabeth II, and his private audience with the monarch was broadcast in the 1969 BBC documentary, Royal Family.

Graves was one of 16 Great War Poets memorialised on a slate stone opened to the public in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner on 11 November 1985. Of the 16 poets commemorated that day, Graves was the sole survivor.

For all the tranquillity that Majorca provided, the writer was still haunted by the ghosts of the First World War. As late as 1957, Graves wrote an affecting poem, The Face in the Mirror, about how, even in old age, he could never escape his dreadful memories of the frontline.

It opens:

“Grey haunted eyes, absent-mindedly glaring

From wide, uneven orbits; one brow drooping

Somewhere over the eye

Because of a missile fragment still inhering,

Skin deep, as a foolish record of old-world fighting”

Nunez recounts an anecdote that underscores the enduring suffering that the First World War inflicted on the writer. “I’ll never forget a story I heard from the actor Julian Glover, who was Graves’s godson and plays his father in the movie, of all things.

“He was at Graves’s house in Deia a couple of years before Graves passed away. They were all having dinner, and Graves was silent. You could see he was somewhere else. And then, all of a sudden, he just said, ‘I’ve killed people.’ And the whole table just stopped. What can you say? That trauma can’t go away.”

In his introduction to Goodbye to All That, Graves laid out his reasons for writing the book. “It’s an opportunity for a formal goodbye to you and to you and to you and to me and to all that; forgetfulness, because once all this has been settled in my mind and written down and published, it need never be thought about again.”

Was that wishful thinking?

Yes, Graves was capable of saying goodbye to all that, but he was never quite able to say goodbye to PTSD.

The Laureate is in cinemas now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments