Is creating octopus farms to rear them for food really a good idea?

Researchers and activists have been appalled by plans to farm the complex creatures, writes Sean T Smith

Underestimate octopuses at your peril. In 1875, staff at the Brighton Aquarium were mystified by the disappearance of lump fish over several consecutive nights. Gradually, it dawned on them that, under cover of darkness, an octopus had been climbing in and helping himself to a midnight feast before returning to his own neighbouring tank in the morning.

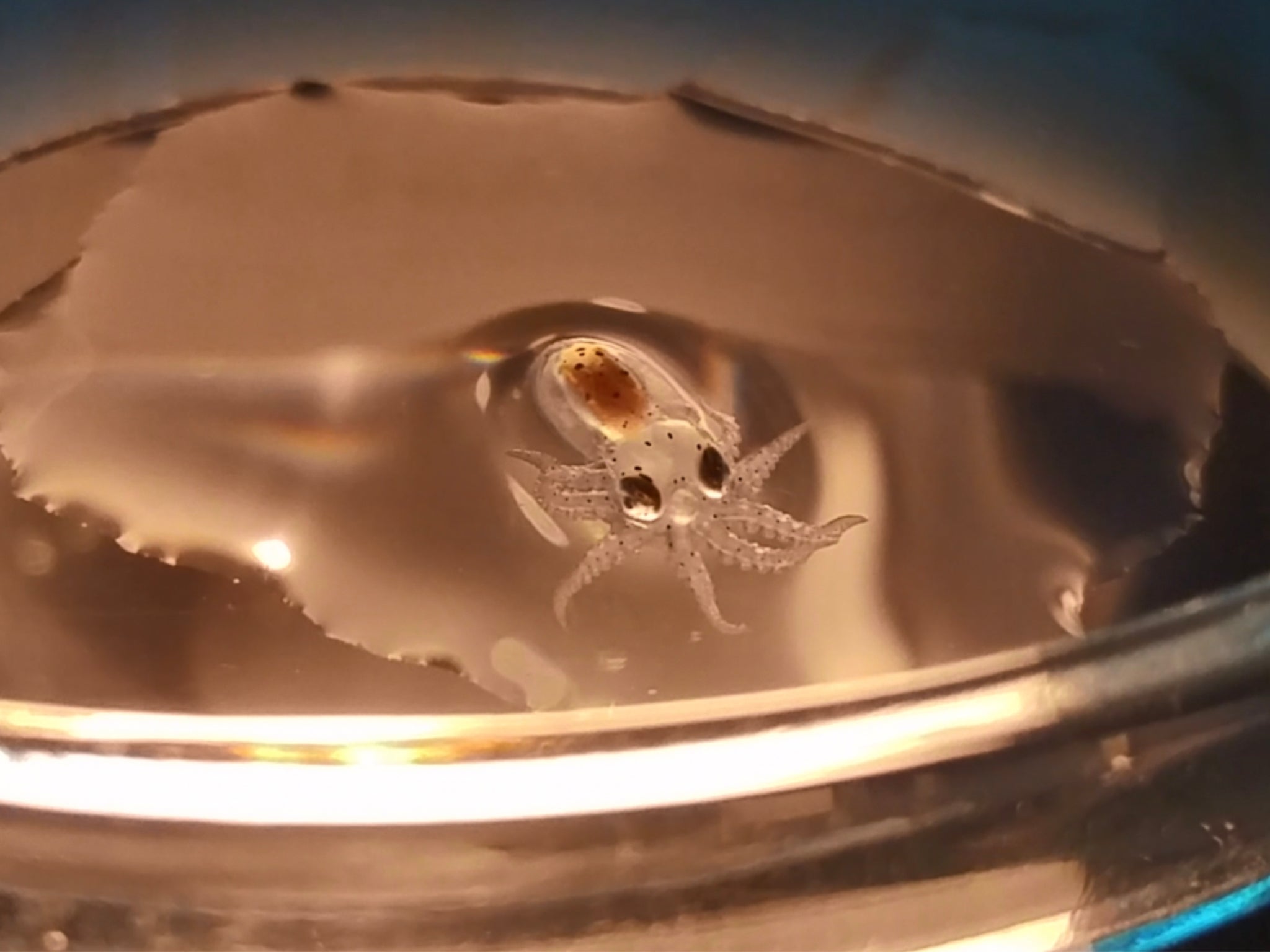

Nowadays when Professor Peter Tse enters his laboratory at Dartmouth College, he often finds his octopuses “linking arms” over the tops of their partitioned tanks. As a professor of cognitive neuroscience, he explains that octopuses offer invaluable insights into how intelligent life emerged.

“If you hope to understand features like cognition and consciousness, you need to look at what evolution has come up with elsewhere,” he tells me. “Octopuses started out as a snail but evolved to become so very intelligent because of an evolutionary arms race. They’re so vulnerable because everyone in the ocean wants to eat them. That’s why they have to slink and hide and why they’ve become so cunning.”

For a creature that has a reputation for being solitary it’s surprising how many octopuses become extroverts when it’s safe to do so. “It’s easy to form relationships with them,” says the professor. “They come to the front of the tank to play. It’s not that they need to be touched for any survival reason, sometimes they just want to be touched for the sake of it. In terms of their personality, they’re kind of like a cat – solitary, happy to be on their own but they do seek out social interaction when they feel like it.”

Prof Tse explains why animals such as cats provide a useful point of comparison when studying octopus intelligence.

“If you just look at the cortex, where most of the neuroscientists would locate sentience and consciousness, octopuses have around 500 million neurons in their body – the same as a cat has in its cortex. And each arm has its own sort of mini-brain so you might say they have nine brains, each making its own decisions.”

Tse goes on to explain that octopuses are capable of distinguishing between different human faces and have distinctive personalities. Researchers have shown that octopuses can also remember routes through mazes, solve problems and even use tools.

Given the weight of evidence that they are intelligent creatures, researchers like Prof Tse have been appalled by recently revealed plans for octopus farms.

Ever since its 2019 announcement that it had managed to successfully breed octopuses in captivity, the massive aquaculture multinational Nueva Pescanova has been working out how to transfer mass-production fish farming methods to octopuses.

These complex, inquisitive, intelligent, mostly solitary, and light-averse animals will be kept in crowded, barren, completely artificial tanks and exposed to 24-hour periods of constant light

We currently consume 420,000 metric tonnes of octopus each year. Octopus has long been an established delicacy in Spain, Italy, Greece and Japan but its growing popularity in the US and other wealthy countries is swelling demand globally.

And given the fact that a maturing octopus piles on five per cent of its body weight in just a single day, the aquaculture industry was always going to notice its potential profitability.

But it was only in March, when Nueva Pescanova’s application to obtain an aquaculture licence was revealed by the animal advocacy organisation Eurogroup for Animals, that the scale of its plans became clear.

By building the world’s first indoor octopus farm in Gran Canaria, Nueva Pescanova’s 1,000-tank facility is projected to produce 3,000 tonnes of octopus meat each year.

“If these plans are correct, these animals will experience incredible amounts of stress and suffering. These complex, inquisitive, intelligent, mostly solitary, and light-averse animals will be kept in crowded, barren, completely artificial tanks and exposed to 24-hour periods of constant light,” alleges Keri Tietge from Eurogroup for Animals.

For octopus farming to be economically viable, Tietge’s group has calculated that Nueva Pescanova will need to rear a million octopuses each year, and as a result each cubic metre of water will be home to 10 to 15 octopuses.

According to Tietge, replicating the same business model used in other types of fish farming, Nueva Pescanova is ignoring the salient fact that territorial creatures like octopuses are particularly ill-suited to such close physical confinement.

“We know from past research under similar circumstances that octopuses could become aggressive and turn toward cannibalism or self-mutilation. We also know they are prone to injuries in aquaculture tanks due to their fragile skin and absence of any internal or external skeleton for protection,” claims Tietge.

But Tietge hopes that the octopus will escape a factory-farmed future because of a recent redesignation in their status as “sentient animals”.

An extensive review commissioned by the UK government and led by the London School of Economics concluded very plainly that cephalopods – including octopuses – are “sentient animals”.

Defining sentience as the capacity to have feelings such as pain, pleasure, hunger, thirst, warmth, joy, comfort and excitement, LSE researchers evaluated the findings of 300 scientific studies before recommending that, like all cephalopods, octopuses should be regarded as “animals” for the purposes of the 2006 Animal Welfare Act.

The proposed method of ice slurry is shown to cause a painful and prolonged death, sometimes lasting for hours, and is being phased out of other aquaculture sectors for these reasons

The UK Animal Welfare Bill has since been amended to reflect this. But for the time being at least, the EU’s existing animal welfare law does not apply to invertebrate animal species, so there is currently no protection for octopuses when farmed.

Prof Tse regards their mastery of disguise as the strongest evidence of octopus sentience. When hiding from predators octopuses don’t just change their colour to match nearby coral, they camouflage themselves by replicating its texture and shape too.

“You can infer from that that they must be able to see three-dimensional shapes and that they can gear their camouflage towards what they regard as the viewer, implying awareness of perspective,” he says.

Prof Tse believes that it’s also very apparent that octopuses experience pain. In fact, it’s likely that they’ve evolved to learn from painful experiences.

When one of the laboratory octopuses lost a tentacle to a water fan, it behaved in a way that was entirely consistent with nursing an injury, stroking the wound for weeks before the limb regenerated and grew back over the next few months.

That’s why, according to critics, perhaps the most disturbing aspect of Nueva Pescanova’s licence application is the method they’ve chosen to mass cull thousands of octopuses simultaneously.

By opting for the most traditional and cost-effective method of killing factory-farmed fish – immersing them in an ice slurry to lower the core body temperature and so achieve death by hypothermia – Nueva Pescanova has incensed animal rights activists.

“The accepted standard for humane slaughter is to use a method proven to cause loss of consciousness in one second,” explains Tietge. “The proposed method of ice slurry is shown to cause a painful and prolonged death, sometimes lasting for hours, and is being phased out of other aquaculture sectors for these reasons. There is currently no known or approved method for the humane slaughter of octopuses for commercial farming purposes. It is entirely inappropriate and inhumane and would cause terrible suffering for these sentient animals.”

In previous statements, Nueva Pescanova has said: "The levels of welfare requirements for the production of octopus or any other animal in our farming farms guarantee the correct handling of the animals. The slaughter, likewise, involves proper handling that avoids any pain or suffering to the animal.”

Giant aquaculture multinationals like Nueva Pescanova argue that fish farms are the best way to avoid overfishing, by creating sustainable alternatives. "Aquaculture is the solution to ensuring a sustainable yield," the company has said. They also argue that fish farms reduce destructive fishing methods like sea bed trawling, for example.

Can we really justify increasing our use of intensive animal rearing for a food that is a luxury and not a staple component of our nutritional intake?

But this argument is contested by environmental groups. Far from protecting fishing stocks, they argue, by feeding farmed animals with wild animals, or foodstuffs derived from them – like fish meal and fish oil – aquaculture hollows out the food chain and compromises the marine ecosystem with alarming implications for the environment.

“Forage fish play a key role in the marine environment as they are crucial in transferring energy from primary producers to higher trophic level species, including large fish, marine mammals, and seabirds,” explains Dr Elena Lara of the environmental group Compassion in World Farming.

Dr Lara believes that using wild-caught fish for octopus feeds would in fact create food security issues in regions such as west Africa, southeast Asia, and South America, where the main industrial fisheries are located. Environmental campaigners also argue more generally that fish farms pollute coastal waters with chemical waste and faeces.

Currently, 50 per cent of fish consumed in the world comes from aquaculture and the figure is projected to rise to 66 per cent by 2030.

As professor of animal organisation studies at York University, Lindsay Hamilton is used to weighing up the ethics around industrial animal farming, and she believes that aquaculture poses complex issues.

“We are tangled in what many call the animal industrial complex, and it seems there are no easy paths forward if consumers want cheap, easily available and nutritious food.”

But when it comes to octopus, Hamilton believes its status as a luxury food item simplifies the issue. “Can we really justify increasing our use of intensive animal rearing for a food that is a luxury and not a staple component of our nutritional intake?” she asks.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments