Is this the film industry’s final frontier?

Steven Cutts looks at whether movies shot in space will be a small step or a giant leap for filmmakers

Going to the movies has long been about the experience of another world. Now, in the early 21st century, some in the film industry are about to take this to a new level.

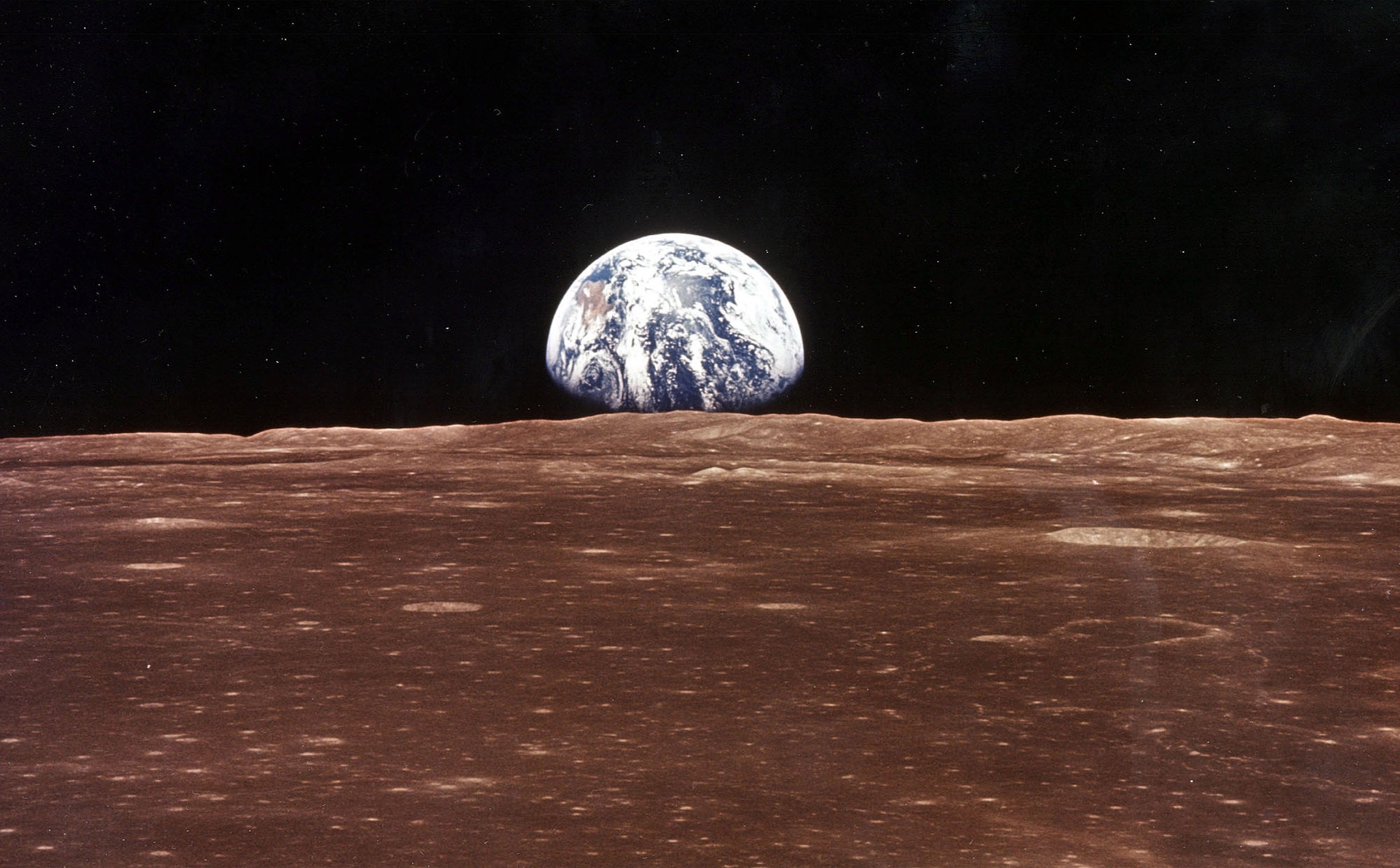

Outer space is seriously being considered as a proving ground for the next generation of movie stars, and there are detailed plans to shoot both in orbit and – in the near future – on the surface of the moon.

Low-to-zero gravity film production is not without precedent. In 1995, innovative director Ron Howard gave a new edge to his Tom Hanks feature Apollo 13 by actually creating a weightless environment to shoot in. Nasa engineers found that it is possible to simulate zero gravity for a short period (about 25 seconds) in a wide-bodied aircraft that flies along a high altitude, parabolic trajectory.

Historically, this technique has been used to introduce new astronauts to the feel of space. Not everybody loves the experience, and the jet quickly acquired the nickname “vomit comet” for precisely this reason.

Howard’s Apollo 13 images on board the vomit comet are certainly striking, but simulated zero-g is no substitute for the real thing. Given the pace of technological advancement, it’s only a matter of time before we see films created entirely in space.

In 2020, Tom Cruise and The Bourne Identity director Doug Liman revealed their plan to travel to the International Space Station (ISS) and shoot their own feature. It looked like they were about to make movie history but then – and not for the first time – the Russians beat the Americans to it.

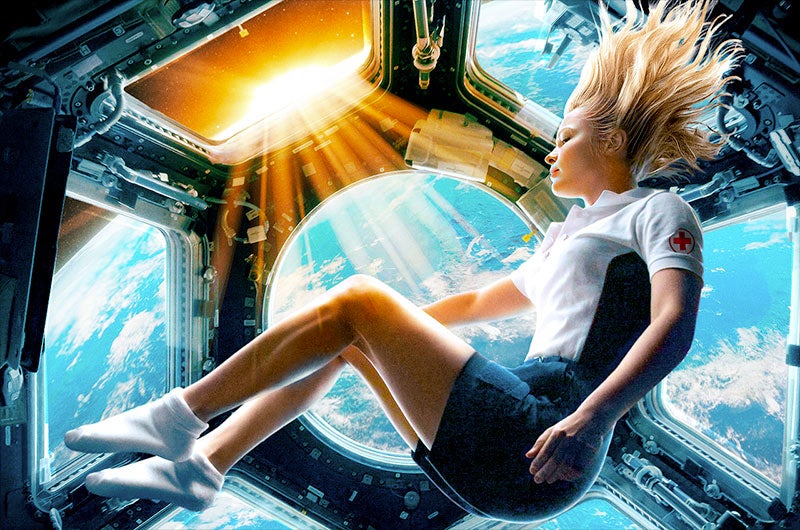

Vyzov is a 2023 Russian-language production that was filmed – at least in part – in low Earth orbit (LEO). The Challenge (in its English translation) is about a cardiac surgeon named Zhenya (played by Russian actor Yulia Peresild) who is sent to the ISS to operate on a cosmonaut (played by a real-life cosmonaut, Oleg Novitsky).

In October 2021, Peresild and director Klim Shipenko blasted off to the International Space Station. The Russian Soyuz capsule can only accommodate three people, so the career cosmonaut Anton Shkaplerov was the only properly trained one among them. The director filmed with a small handheld camera and there was no luxury of a make-up artist. Filming lasted 12 days and the final product has already been released in Russia.

As space firsts go, Vyzov is not that bad. You can watch the trailer on YouTube – some of the shots of people zipping around in zero gravity are noticeably realistic, much more so than anything CGI could create. Whether or not the actual story turns out to be a hit with a global audience is yet to be seen.

It may seem incredible that non-professional astronauts can think about doing this at all, but paying for your own trip to low Earth orbit has been realistic for some time now. In 2001, the American tech entrepreneur Dennis Tito paid $20m to become the world’s first space tourist. Tito had previously worked as a scientist at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and has had a lifelong interest in space travel. Still active in his eighties, he hopes to become one of the first people to orbit the moon in SpaceX’s Starship.

Not everybody is happy about these self-funded explorers going into orbit. In both the Russian and American space programmes, industry professionals have spoken out against non-professionals in outer space. Those of us who are old enough to remember the Challenger disaster of 1986 will also recall the untimely demise of volunteer school teacher Christa McAuliffe. One can never forget the sense of shock that came with that explosion. It was a stark reminder that this kind of adventure is not without serious risk.

In recent years, people like Jeff Bezos of Amazon and Elon Musk of SpaceX have successfully reinvigorated the entire industry of space travel. There are now a number of private companies preparing to send their own space stations into orbit. Many of the designs are inflatable habitat concepts, offering large interiors and, one expects, spectacular views.

On the downside, these kinds of projects are not cheap. Given the immense costs of space flight, it’s unlikely that anyone making a film in orbit will be able to take a full production crew. That said, the advent of reusability in launch vehicles is beginning to reduce the cost to some degree, but actors hoping for a set of make-up artists to accompany them will be in for a wait.

Richard Branson has recently launched yet another Virgin Galactic mission and seems – at long last – to be on the verge of regular tourist flights to the edge of space. Branson’s company is offering its customers four-and-a-half minutes of zero-g, and for some filmmakers this might be enough to record some good footage. Sure, the actual duration of weightlessness isn’t huge, but it’s still nearly 11 times longer than the window Ron Howard had to play with, and will be at a fraction of the cost of a trip to the ISS.

The start-up company Space 11 is seriously suggesting that it could build a film and television studio in low Earth orbit. They say they will produce a reality TV show “on a terrestrial space station, in which athletes, singers, actors, fashion designers and top models undergo training to face events in outer space at zero gravity.” It will be – their website says – “One giant leap for entertainment”. Exactly how credible this approach turns out to be remains to be seen.

Centerboro Productions are reportedly planning a sci-fi thriller Helios with the enthusiastic backing of Bezos and his own space flight company, Blue Origin. Blue Origin and Sierra Space are also working on a new space station to replace the ISS, named Orbital Reef, and it has been suggested that this station could be used as a location for zero-gravity filming.

There are currently several attempts to put humans back on the moon, and whilst costs of a lunar shooting schedule might sound ambitious, there are some filmmakers who regard the moon, with its low-gravity environment, as a much more straightforward location than near-Earth space. China’s National Space Administration (CNSA) has announced its ambition to send people to the moon by 2030, while the Americans are not only hoping to beat them to it, in the late-2020s but also to build the first moon base while they are there.

But for anyone looking to head into space, a key issue is having the right type of spacecraft.

The ISS is in a low Earth orbit of between 250 and 260 miles above our heads, and the Hubble space telescope orbits at about 340 miles. That’s about the distance between London and Edinburgh. Yet despite this relatively near proximity, staying up there is another matter entirely. In order to remain in orbit, a spacecraft needs a downrange velocity of around five miles per second (17,000mph). To put this in perspective, Richard Branson’s SpaceShipOne achieves a maximum speed of 2,000mph, massively short of orbital velocity. As things stand, the only way to overcome this obstacle would be to use a multistage rocket.

Since Nasa retired its space shuttle in 2011, the only country with the ability to blast people into orbit has been Russia. They are able to do this using the venerable Soyuz capsule and a launch vehicle they developed in the 1960s. Short on money, Russian space engineers managed to raise funds from – among other places – Nasa, which needed a lift to the ISS.

But the arrival of SpaceX’s Dragon capsule means it is now possible to take seven passengers into orbit at a time. The vehicle is apparently so easy to operate that some of the SpaceX launches have featured non-professional, fee-paying astronauts. Behind the scenes, the American aerospace company Boeing is also developing its Starliner capsule and, after several delays, might actually get as far as flying one in July of this year.

Meanwhile, another American aerospace company, Sierra Nevada, has been working on a small, winged space vehicle known as Dream Chaser. It too has been beset with delays, the most recent pushing a launch date back until later this year. Designed initially to carry cargo, there are plans to upgrade it to a manned spacecraft, transporting a similar size crew to the Dragon capsule into LEO.

If seven sounds a little small to you, you might prefer SpaceX’s Starship, which boasts that it will be able to carry “up to 100 people on long-duration, interplanetary flights”.

Unfortunately, Starship’s test launch and subsequent explosion back in April means – like all the other projects – this too is some way off delivering on its promises. But once we have the capability to send groups of a hundred people at a time into orbit, a space-based entertainment industry starts to look very real indeed. They might even get to bring a make-up artist along too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments