Ooh, ah, Cantona! The reinvention of a football genius

Eric Cantona thrilled Man United fans, impressed film critics and now – as a singer-songwriter – is being hailed as the new Leonard Cohen. No matter that his lyrics sound like they were written by a depressed teenager on ChatGPT, writes Jim White, his latest reincarnation is a sell-out success, and he’s on his way back to Britain…

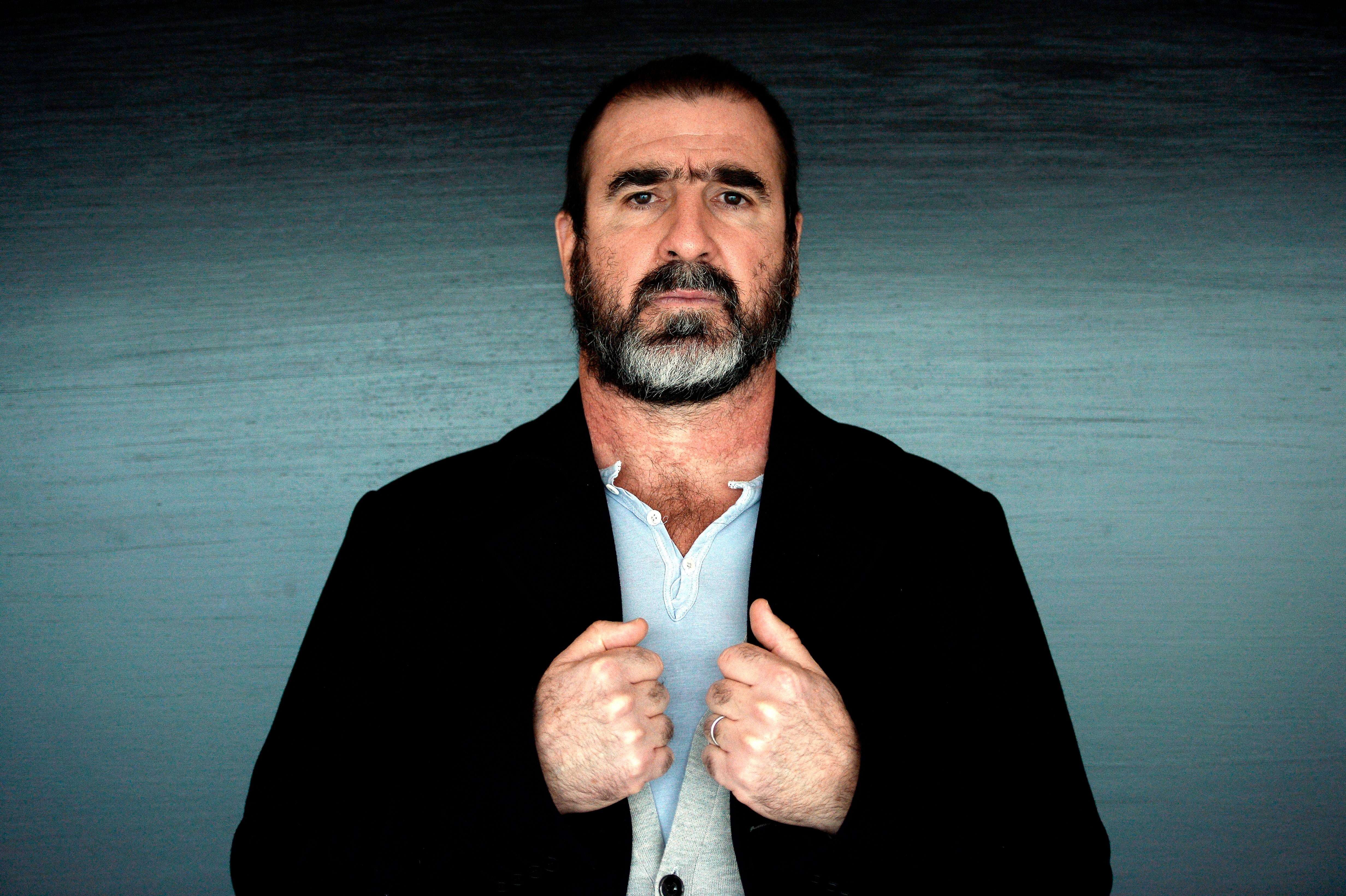

Over the weekend, a 57-year-old singer-songwriter new to the scene made his concert debut with a performance in a small club in Auxerre, southern France. In normal circumstances, his two-hour set would have garnered little attention. But the French media was there in force. This, after all, was no ordinary debutant, rumbling gruffly behind the microphone. This was Eric Cantona.

Among those present, the critic from Le Parisien reckoned the former footballer’s stripped-back show was magnificent: smart, intriguing, his material and performance comparable, they insisted, to Leonard Cohen and Nick Cave. Well, there certainly wouldn’t have been a lot of laughs involved. This is a man who has long taken his work seriously indeed.

“When I was a kid, I had two passions: for art and sport. So I started with football, better I think,” he told the BBC’s Colin Paterson, who was at the gig. “Now I can sing until the end of my life. I have a deep need of expressing myself.”

And, being Cantona, as he goes about the process of expression, he is not lacking in self-confidence. When Paterson asked if he might like one day to support The Rolling Stones, his answer was swift and unequivocal.

“No,” he said. “I am a headliner. It’s why I cannot understand you. Maybe the Stones can support me.”

Next week, Cantona brings his musical act across the channel. He will perform a couple of sold-out shows in Manchester and London, before heading to Dublin. And never mind that his self-penned lyrics sound as if they have been written by a depressed 13-year-old with access to ChatGPT (“Like a red snake in the water/In mind a winning number/Listen to the silence over the fear/The deep ocean that we can’t hear,” runs the verse of “The Friends We Lost”) the response will be close to euphoric.

But then, particularly back in Manchester, the city where he was lauded like no other, Cantona could stand on stage and do a rap version of “The Birdie Song” and the ovation would threaten the roof. Because for a whole generation of Manc football fans, Cantona remains of endless fascination, a unique figure in the game. And I count myself firmly in their number.

As a footballer, he always knew he was different. He regarded the game less as a sport, more as a canvas for self-expression. This is not to suggest he was an artist in the way Lionel Messi, Diego Maradona or George Best were. Though he scored some beautiful goals, and delivered some exquisite passes, his playing talents were much more physical than balletic.

But, like no one before or since, he understood the possibilities the game offered for drama. No one has been as adept as he was at turning the football pitch into a stage. While Roy Keane used it as an extension of warfare, while David Beckham perfectly appreciated how to use his sport to enhance his personal brand, while Cristiano Ronaldo saw it as a giant mirror to reflect his image of himself, Cantona reckoned football was all an act. His goal celebrations, his presence, his rare gnomic utterances: this was football as theatre.

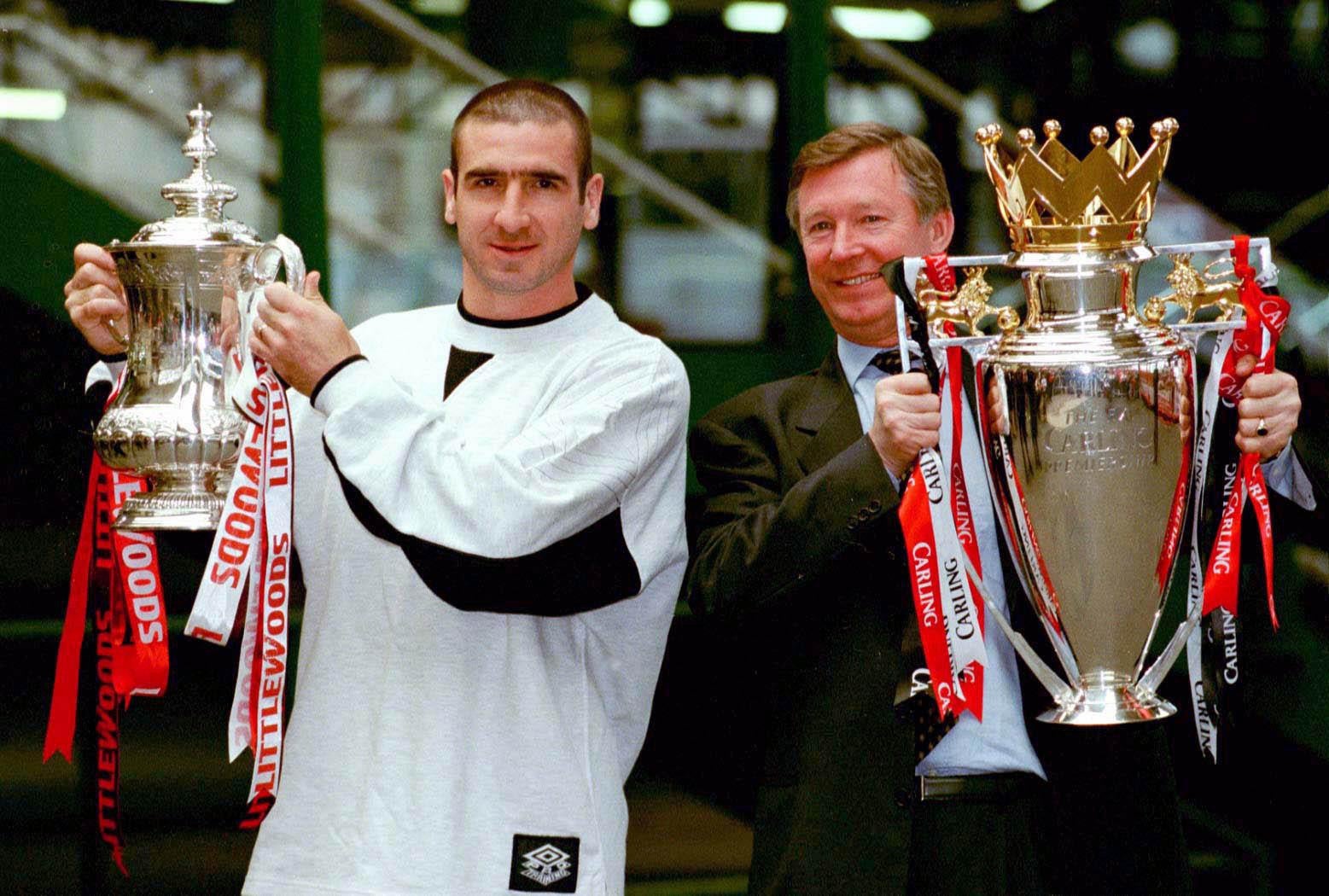

And how we lapped it up. To watch him during his time at Manchester United, acting as the catalyst to transform Alex Ferguson’s first great side from nearly men to serial winners, was to see someone in total control – a conductor determining the pace and rhythm of everything going on around him.

Even his misdemeanours were pieces of performance art. And when he made them, he seized his moment to squeeze maximum attention. I was there at the press conference when he delivered the “seagulls follow the trawler” line that came to give meaning to his time at United. What was most striking about it was the fact he took a sip of water in the middle of delivering his lines, as he admitted much later, solely to stop himself from corpsing at the absurdity of it all.

His legend developed like no other. For Manchester United fans he became the figure that defined their assumed point of difference. Even today, some 25 years after his retirement, the advert taken out by a T-shirt company on the back of this month’s edition of the fanzine United We Stand displays far more designs featuring Cantona than any of the current players. He remains their man.

And over the years he has done nothing to diffuse that sense of differentness. When he gave up playing, appreciating that his physique was no longer capable of mastering the game as it once had, he did not follow the standard line of pursuing management or punditry. Nor did he have time for the kind of commercial opportunity his fame offered in the manner his teammates Beckham and Gary Neville so vigorously embraced. Instead, he continued doing what he had done as a player: he explored platforms from which to express himself. First he became an actor. And he wasn’t at all bad. He was excellent in movies like Elizabeth, The Salvation, and particularly Ken Loach’s sublime Looking for Eric, in which he revelled in self-parody as the imagined mentor of a Cantona-obsessed depressive.

And whatever he did, he retained a carefully cultivated air of mystery and otherness. Back in 2006, his old club was involved in a hubristic publishing venture called the Opus. This was a lavish, giant book detailing United’s history that retailed at nearly £3000. Cantona was asked if he would be photographed for the book. He said he would, but only if he could direct the shoot as he wished. The resulting pictures are extraordinary. Not for him soft focus shots juggling a ball. These are of a naked Cantona covered in blood, others feature him apparently being tarred and feathered, one is of a full-on crucifixion. Just a shame so few copies of the project were actually sold: these were shots so jaw-dropping they deserved a far wider audience.

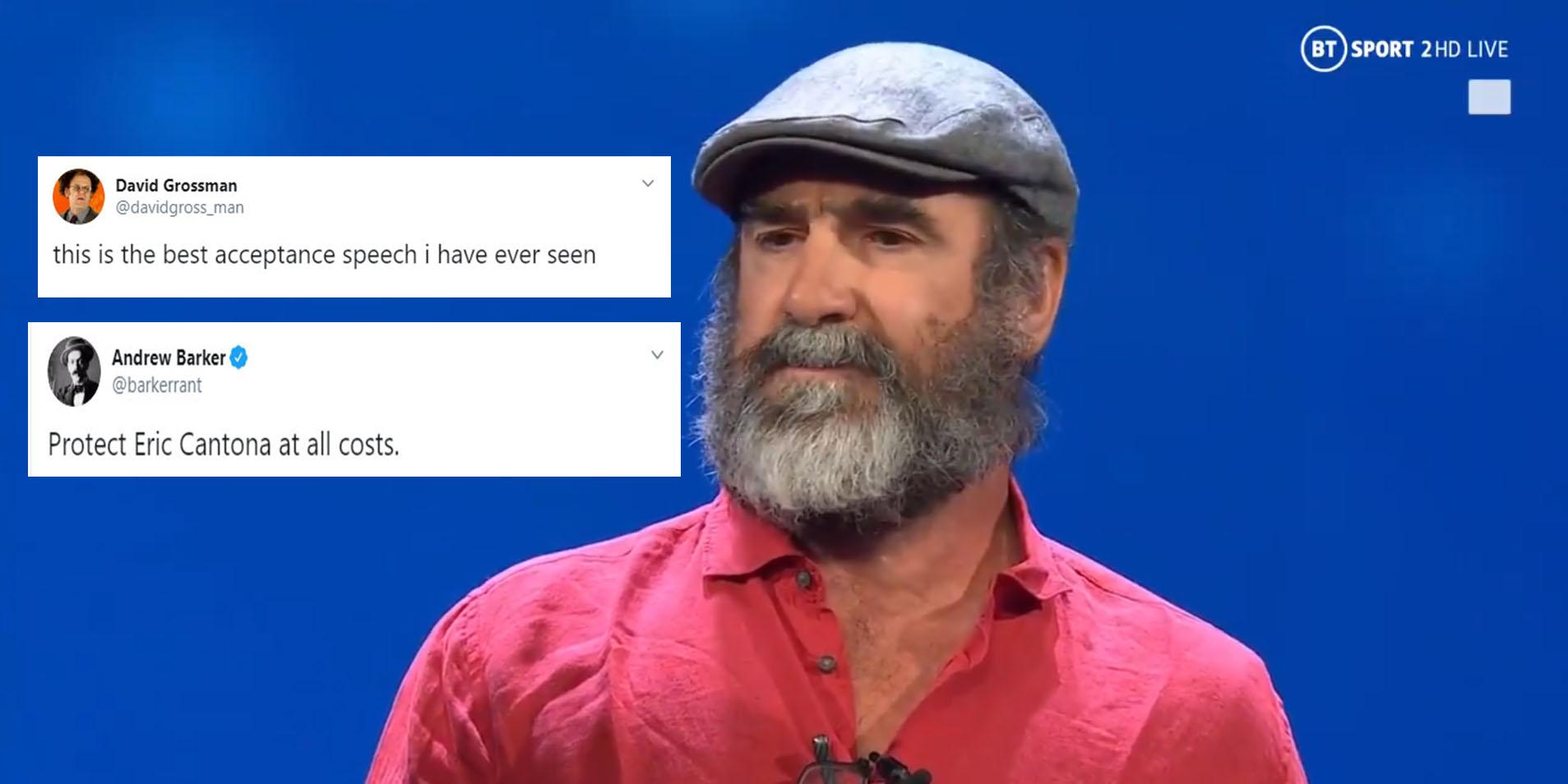

Still now, on his rare public appearances, he never misses the opportunity for theatrics. At the 2019 Champions League draw, he was presented with a lifetime achievement award by Uefa. When he came up to accept his prize, wearing a crumpled red shirt and flat cap, he was asked if he wanted to say a few words. Indeed he did, he said, before delivering an apocalyptic vision of a future in which, with eternity guaranteed through cell replacement, “only accidents, crimes, wars will still kill us but unfortunately, crimes, wars, will multiply.” And he concluded: “I love football. Thank you.”

In the audience were the then two greats of contemporary football: Ronaldo and Messi. And the baffled look the camera catches on their faces as he finishes is a work of art in itself.

We should, perhaps, then not be surprised at his latest mode of delivery. He told the French press that he had been thinking about expressing himself through song for some time, but that lockdown gave him the time and inclination to pursue the idea. Listening to the tracks on his newly released EP, he has clearly been given hefty assistance by some deft production. It cannot be denied, however, that his throaty, enigmatic growling – to call it singing would be pushing definitions to the edge of credibility – really works. He even makes lines like “Watch the trees when the others fall/The hall of love is much too small” sound profound.

That is Cantona, a man routinely capable of making anything and everything seem dramatic. And in private he is no different. About 10 years ago, I interviewed him over lunch in a Paris bistro. For me, it was a moment of real import. For him, not so much. Nevertheless, he was charming, engaging, frank. At the end, I called for the bill. When it arrived he grabbed it from me and insisted on paying.

“Your pounds,” he said, as he made a dismissive sweep of his hand, “are no good to me.”

Even an act of quiet generosity Eric Cantona managed to turn into a moment of theatre.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments