New map of Earth’s tectonic plates ‘could help predict natural disasters’

In new research, scientists have redrawn the boundaries of our planet’s architecture, Andy Gregory reports

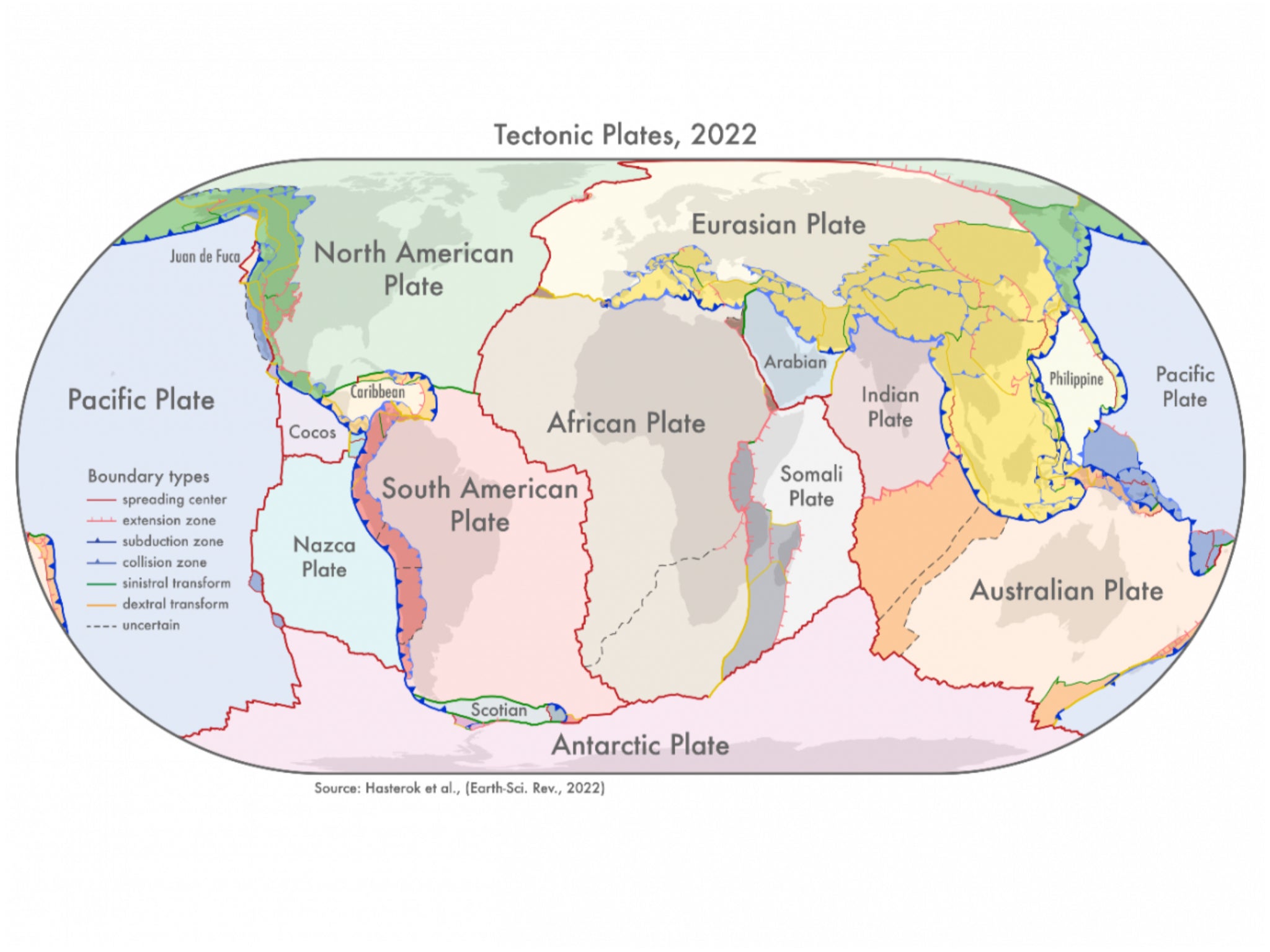

New scientific models mapping the Earth’s tectonic plates could help to sharpen our collective understanding of natural disasters like earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, scientists have said.

The parts of the planet’s crust which form our modern continents are thought to have taken shape billions of years ago, and their resulting shifts – including the formation the first supercontinent, known as Vaalbara, to the break-up of Pangea 65 million years ago – are vital our understanding of the Earth’s modern architecture.

But scientists’ standard models of the Earth’s plates – those used in classrooms and geology textbooks – have not been updated since 2003, according to Dr Derrick Hasterok, of the University of Adelaide’s department of earth sciences.

In new research published in the journal Earth-Science Reviews, Dr Hasterok and his team have created three new models which provide a clearer view of the Earth’s architecture and which he hopes will, among other benefits, help to improve our understanding of the risks from geohazards.

“We looked at the current knowledge of the configuration of plate boundary zones and the past construction of the continental crust,” Dr Hasterok said.

“The continents were assembled a few pieces at a time, a bit like a jigsaw, but each time the puzzle was finished it was cut up and reorganised to produce a new picture. Our study helps illuminate the various components so geologists can piece together the previous images.”

The team produced three new models: those showing the earth’s plates; its smaller geological “provinces”; and its 26 orogenies, which relate to the process of mountain formation and, according to Dr Hasterok, “have left an imprint on the present-day architecture of the crust”.

His team believe they have made significant improvements.

“Our new model for tectonic plates better explains the spatial distribution of 90 per cent of earthquakes and 80 per cent of volcanoes from the past two million years whereas existing models only capture 65 per cent of earthquakes,” said Dr Hasterok.

Their new plate model includes several new microplates, including the Macquarie microplate which sits south of Tasmania and the Capricorn microplate which separates the Indian and Australian plates.

Dr Hasterok said: “The biggest changes to the plate model have been in western North America, which often has the boundary with the Pacific Plate drawn as the San Andreas and Queen Charlotte Faults. But the newly delineated boundary is much wider, approximately 1500 km, than the previously drawn narrow zone.

“The other large change is in central Asia. The new model now includes all the deformation zones north of India as the plate bulldozes its way into Eurasia.”

This newly improved plate model “can be used to improve models of risks from geohazards”, Dr Hasterok said, while the province model “can be used to improve prospecting for minerals”.

More than 200,000 earthquakes are recorded globally each year, however the true number is thought to be significantly higher.

While technological advances are improving our potential ability to forecast looming geological hazards, it remains impossible to predict exactly when and where earthquakes will take place.

According to the website of the Geological Society of London, the oldest group of its kind in the world, current forecasts “are based on data gathered through global seismic monitoring networks, high-density local monitoring in known risk areas, and geological field work, as well as from historical records”.

“Forecasts are improved as our theoretical understanding of earthquakes grows, and geological models are tested against observation,” it adds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments