Why did Biden cling on for so long? Because power is delicious and he was addicted to it

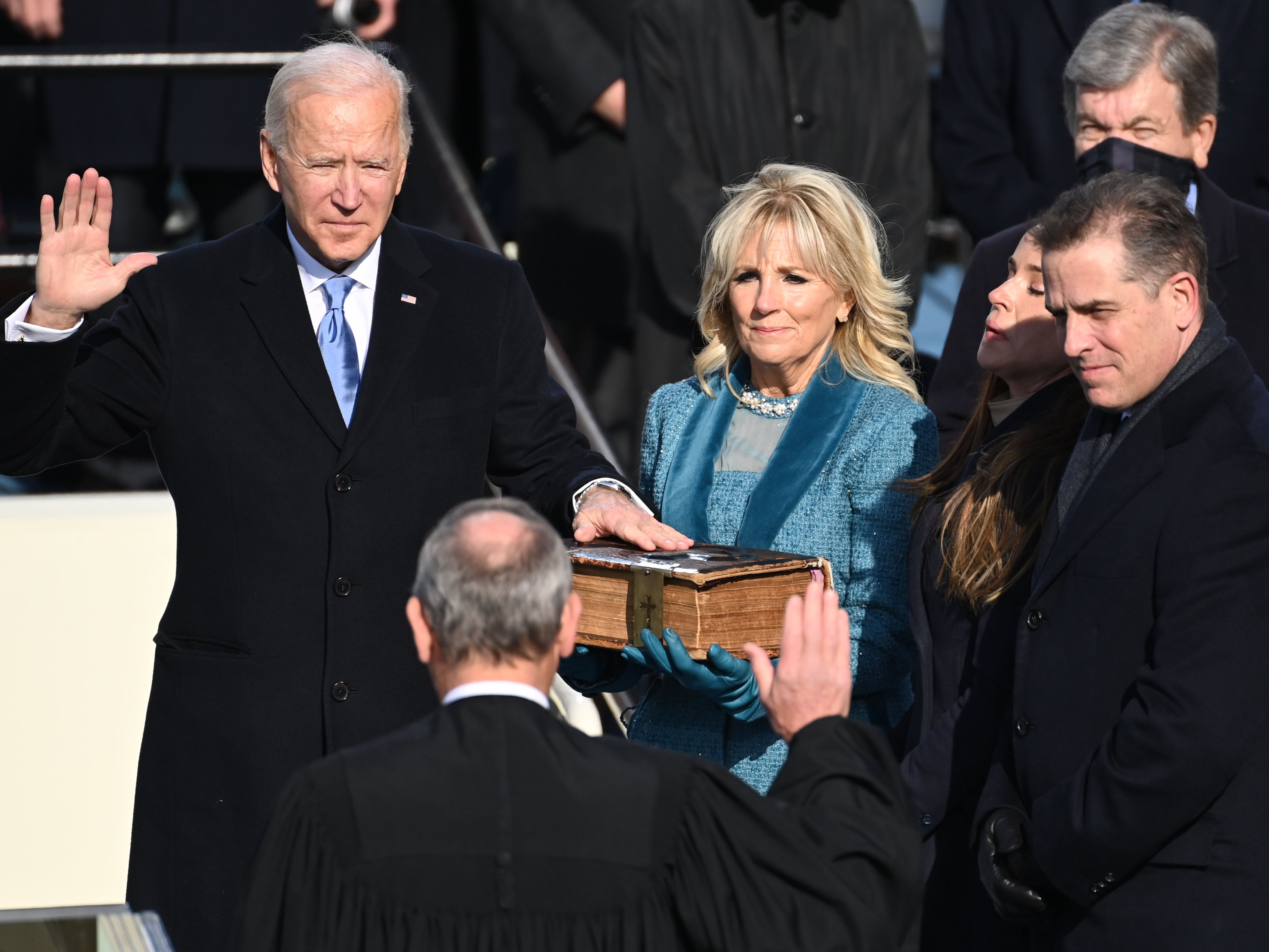

Joe Biden was written off as an incapable dithering old man, but despite what Donald Trump says, he’s been good for America. Former foreign secretary Jack Straw looks back at how history will remember the 46th president and what the next chapter of the US and UK’s special relationship looks like for Labour now

There’s one word to explain why Joe Biden had been defying all known laws of political gravity for so long. Power. It’s delicious. It can consume every minute of every day. It’s highly addictive. It’s very easy to consider yourself utterly indispensable, if not possessed of a unique, divine purpose.

Without it, nothing lies ahead but darkness.

But no one within a democratic system that I’ve ever come across, at home or abroad, has been willing to go through what Theodore Roosevelt called the “dust and sweat and blood” of high office – unless they are ready to spend themselves “in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly”.

Yes, Biden was addicted to his power. But that’s entirely understandable. Who wouldn’t be?

A US president is the most powerful leader in the world because they are commander-in-chief of the world’s strongest armed forces, with twice the spending of China, and dwarfing that of the whole of the EU and UK combined, built in turn on the world’s strongest, and most innovative economy. They literally hold the future of mankind in their fingers.

But in many areas, their discretion is far more fettered than that of a UK prime minister with a majority in the Commons. A president is beholden to Congress for money, and even his discretion on foreign policy may be seriously constrained by the Senate.

As a senior British minister under two administrations, my personal contact with both President Clinton, and then President Bush, was limited. But I saw enough to be struck by the apparently eerie calm around the president.

There was a buzz around the staff in the West Wing, for sure, but I witnessed none of the freneticism which could sometimes overcome the prime minister’s own “den”, especially on a Wednesday when Prime Minister’s Questions were looming, or any other time when a crisis had erupted. A president can pick and choose when they submit themselves to questions. There’s no such luxury for a PM.

In early February 1998, Tony Blair asked me to accompany him on his first official government visit to Bill Clinton.

No one knew when the dates of the trip were organised that this would coincide with the eruption of the Monica Lewinsky scandal. A couple of days before, Clinton, ever the casuist, had told an incredulous press pack that he “did not have sexual relations with that woman”. The US media were out for his blood.

While railing against the iniquities of the US press (which seemed mild compared to the UK press at the time), Clinton decided that we should go ahead with a four-hour seminar on the “Third Way” (remember that?) in an upper room of the White House.

There were no interruptions. It might as well have been a room off Harvard Yard, or in an Oxford college. It was barking. I reflected that if a similar situation had happened in the UK, the prime minister would not have survived (not even Boris Johnson).

This trip was capped with a fabulous White House banquet, including a jam session featuring Stevie Wonder and Elton John. For that trip, as Tony’s “ranking minister”, I was paired off with the vice-president, Al Gore.

I spotted two things about Gore. One was a gargantuan appetite for cakes and buns; the other was that he was awkward in the company of strangers, with a rather patrician, “preppy” air about him – which may explain why he was unable hands-down to beat George W Bush in the 2000 election.

Bush was, in part, preppy himself. He attended Andover College – one of the oldest private schools in the US, then Yale. But he also cultivated the image of a Texan redneck, and had a wonderfully easy manner about him. He was open to new ideas.

Despite the constraints on the office, and the relentless efforts of the Trump Republicans to thwart his every move, Joe Biden can look back on significant achievements in his period in office as president

When she was secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice had me in to see Bush to explain why I thought the US should engage with Iran in the nuclear talks that France, Germany, and the UK had started.

Again, the calm in the room, compared with No 10, was striking. He joshed with his staff, explaining that he had got a mediocre degree at Yale, while all the brains in the room came from Condi and Bush’s national security adviser, Stephen Hadley.

Despite the constraints on the office, and the relentless efforts of the Trump Republicans to thwart his every move, Joe Biden can look back on significant achievements in his period in office as president.

The US-led withdrawal from Afghanistan was a shambles, but against that has been Biden’s clear-eyed leadership of Nato, and his support of Ukraine, to resist its invasion by Russia. He helped galvanise the European Union into an increasingly tough stand against Russia, notwithstanding the nervousness of some countries with substantial reliance on Russian energy, particularly Germany.

His China policy has been tough, too. It acknowledges the mutual dependence of the US and Chinese economies, but has imposed restrictions on the export to China (and some other countries) of microchips above a certain capability threshold, especially those used for AI and military applications, and has banned the export of chip-manufacturing machinery.

Biden’s misnamed but landmark Inflation Reduction Act won’t do much to reduce inflation – it’s already below 3 per cent. Rather, it represents the largest public investment, at least $500bn, since Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal in the 1930s.

It is aimed to strengthen domestic manufacturing and employment, improve wages, lower household energy prices, promote green energy, as well as reducing the costs of prescription drugs (a huge issue for many families). It took all of Biden’s ingenuity, and that of his collaborators in Congress, to get it through in the teeth of Republican opposition.

The US economy has continued its strong growth (far outpacing Europe). Over 200,000 jobs were added last month. US stock exchanges have shown astonishing resilience through Biden’s term.

One of Donald Trump’s many charges against Biden is that he has failed to rein in illegal migration. The irony of this, which will no doubt be lost on Trump’s supporters, is that Biden would have been far more successful but for a cynical veto by Republicans in the House. Biden got through a potentially effective bi-partisan bill in the Senate, only to have it blocked, on Trump’s instructions, in the lower Chamber.

Even on abortion, Biden was able to find something of a workaround through the barriers which the Supreme Court and Republican state-level legislatures had erected against the right of abortion, by ensuring that termination drugs are available in anti-abortion states.

Of course, Labour is ideologically much nearer the Democrats than the Republicans. Well before his 1997 victory, Tony Blair had invested a lot of energy in developing his relationship with Clinton.

Bush’s election in 2000 was a surprise, and very narrow (losing the popular vote by over half a million, but winning the electoral college by four).

Blair worked hard to overcome the innate suspicion of the Republicans, and cemented his relationship with Bush by “standing shoulder to shoulder” with him in the immediate aftermath of 9/11.

The moral is that you cannot choose the foreign leaders you are going to face, and you shouldn’t try. Keep out of it. It doesn’t surprise me that Sir Keir Starmer has refused to discuss his relationship with Kamala Harris, adding that it is “for the Democratic Party to decide who they want to put forward”.

Biden’s renunciation of a second term has certainly opened up the prospects for the Democrat candidate (whoever that is), and will make for a more interesting contest. But the odds must still be on a Trump victory.

There is a “special relationship” between the UK and the US on intelligence, security, defence and some foreign policy issues – but on little else, and certainly not on trade, where both US parties have become more protectionist in recent years.

It’s also not a relationship of equals. Every British prime minister knows that we need them more than they need us. And we have to get alongside them whoever ends up in the Oval Office. It comes back to power. Who has it and what they do with it affects us all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments