A nation seized by fear: The sinister side of ‘safe’ Rwanda

As Britain prepares to send the first asylum flight to east Africa after seeing off opponents in the courts, critics warn that Rwanda is no safe haven

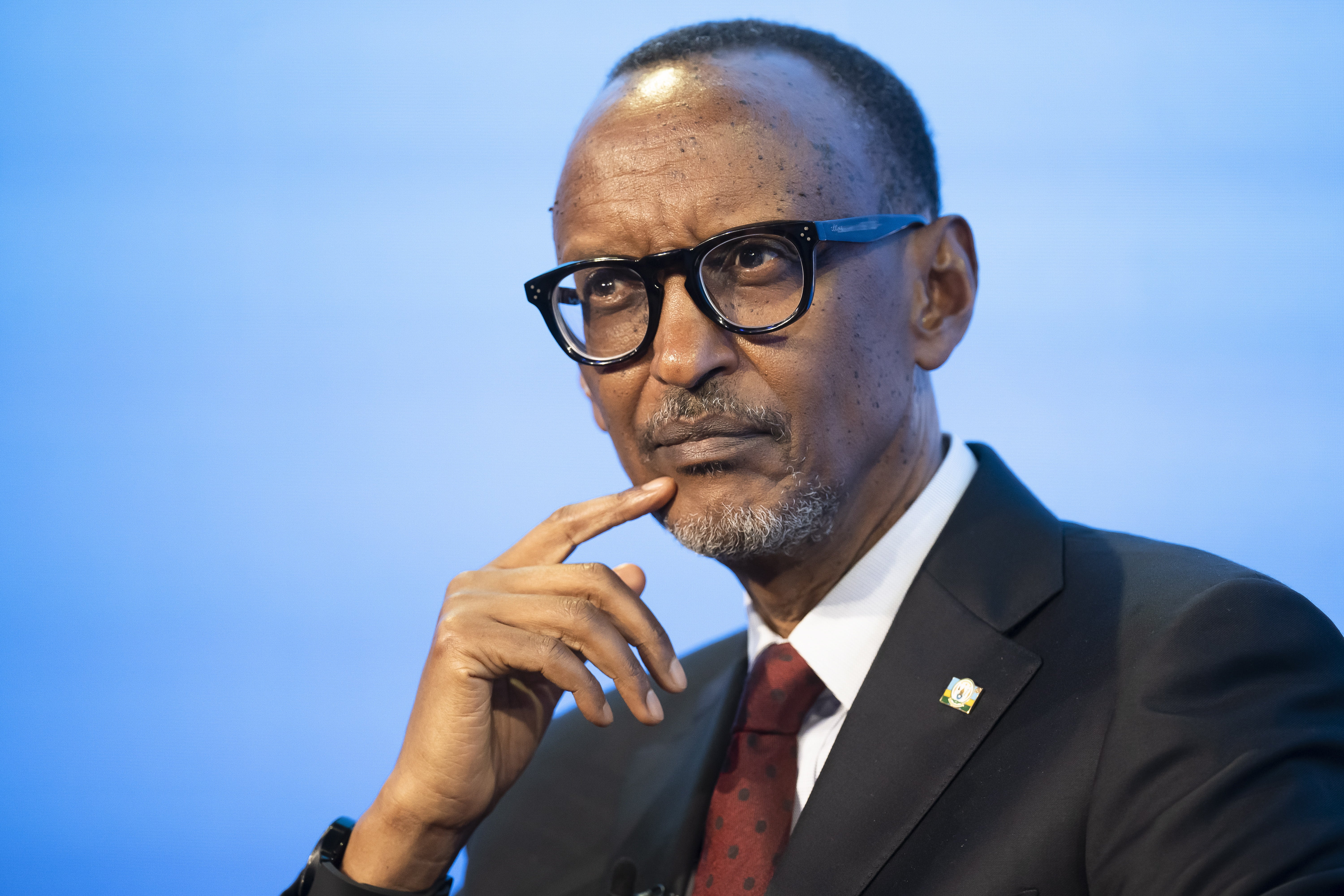

Boris Johnson’s depiction of Rwanda as “one of the safest countries in the world” overlooks the plight of those that get on the wrong side of president Paul Kagame.

While visitors to the tiny east African country generally come away impressed by its cleanliness and safety, rights groups have long been sounding the alarm. Behind the scenes, they say, Rwanda is a nation seized by fear.

“It’s equivalent to walking into a clean house and knowing that behind a closed door people are screaming, and continuing to sit down and have your tea, saying well at least the house is clean,” Carine Kanimba, the daughter of former Kigali hotel manager and dissident Paul Rusesabagina, told The Independent.

Rusesabagina’s efforts to save 1,000 lives during the 1994 genocide saw him depicted in Hotel Rwanda, but in 2020 he was abducted in Dubai, taken to Rwanda and jailed for 25 years.

The UK’s controversial deportation agreement with Rwanda, reportedly dubbed “appalling” by Prince Charles, has shone a new light on Mr Kagame’s repressive tendencies, just weeks before Rwanda hosts the Commonwealth heads of government meeting.

On Monday, British home secretary Priti Patel’s controversial plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda was given the go-ahead by the Court of Appeal.

Judges rejected a last-ditch attempt by campaigners to have the first flight blocked, which could now go ahead on Tuesday.

In a turbulent region, western leaders have long lauded Rwanda as an economic miracle and a beacon of stability, having transformed itself since 800,000 people were killed in a few weeks of uncontrollable violence three decades ago. Strong economic growth has Rwanda aspiring to middle-income status by 2035.

Mr Kagame, 64, raised in a Ugandan refugee camp, gets credit for all of it. Having led the rebel forces that brought the genocide to an end, he has been president since 2000. A string of western leaders have cast him as a visionary.

Experts say the UK-Rwanda migration agreement presents an opportunity for Mr Kagame to improve Rwanda’s image by solving a western problem, while drawing vital funds in the process. This year 10,000 people have made the perilous journey across the Channel on small boats from France. The UK and Rwanda say the policy will pull the rug from under well-paid people smugglers.

Yet providing asylum seekers with one-way tickets to Rwanda has been roundly criticised as cruel by rights groups, including the UN’s refugee agency. Last week, a legal challenge was blocked by the High Court and the first plane is due to leave on Tuesday.

“It’s inhumane, it’s unconscionable, it’s cruel,” said Ms Kanimba, 29. “The exchange of people for cash is not right and it’s setting a precedent that is terrible.”

Yolande Makolo, a spokeswoman for the Rwandan government, said the “bold solution” would tackle “the global inequalities of opportunity that drive economic migrants from their homes causing unsustainable levels of demand on the system.”

She added that Rwanda’s history gives it a “deep connection to the plight of those seeking safety and opportunity in a new land”.

Each month, citizens come together to sweep the streets of Kigali; “community work” is not compulsory but many allegedly feel too afraid to sit it out. Meanwhile, in 2018, eight Congolese migrants died when police used tear gas and live rounds to disperse a crowd outside a UN office in western Rwanda, humanitarian investigators found.

According to the Human Rights Foundation, 1.8 million refugees fled Rwanda between 2010 and 2019. However, in the last presidential election, in 2017, Mr Kagame was returned with 98 per cent of the vote.

Dissidents in exile abroad say they face stalking and threats. In a report this month, US-based Freedom House said Rwanda is among the worst perpetrators of “transnational repression” and noted that the UK-Rwanda deal “is quite shocking given how frequently the Rwandan government has gone after Rwandans in the UK”.

Claude Gatebuke, a Rwandan activist, told Freedom House that many Rwandans overseas do not report harassment because of the country’s close relationships with western countries, such as the US and Britain.

Although the landlocked country is already densely populated, open debate over the merits of the UK deal is unlikely in Rwanda, where information is tightly controlled and spies abound.

Opposition politicians, though, have criticised Britain for failing to “own up to its international obligations on the migration issues”.

Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza, the leader of DALFA-Umurinzi, an opposition party, said Rwandan officials should focus on solving issues at home before taking Britain’s vulnerable asylum seekers. Ingabire was jailed for eight years after returning to Rwanda to contest the 2010 election.

For years, western leaders have talked up Rwanda’s successes. Now, though, the UK deal is drawing fresh attention to the less savoury aspects of Mr Kagame’s rule.

“The UK is doing the PR for Rwanda,” said Ms Kanimba. “Their goal is to sanitise the image of Rwanda in order to make themselves feel good about sending vulnerable people to a dictatorship.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments