India looks to coal as power crisis worsens and monsoons arrive

Experts say India’s recurring power shortage is a result of a supply chain problem, not capacity, while slow progress of renewables continues to be a problem, reports Stuti Mishra

The power plants in India that ran dry during the sweltering heatwave in the last couple of months may not get any respite as the temperature drops and brings monsoon showers, despite the government’s frantic efforts to increase the country’s coal production

India has been reeling under its worst power crisis in more than six years as an extreme and early heatwave raised electricity demand, despite record coal production in 2021-2022. But the worst isn’t over for India. According to a recent report by The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), India is likely to face another power crisis in July-August due to a lower pre-monsoon coal stock at power plants.

“The data compiled from official sources suggest that the coal power plants are in no position to address even a minor spike in the power demand and there is a need to plan for coal transportation well in advance,” the independent research agency said in its latest report. “If coal stocks are not replenished to adequate levels before monsoon, the country might be heading towards yet another power crisis in July-August 2022,” said CREA.

While initial reports suggested that the respite to temperatures brought in by monsoon, and fall in irrigation-driven electricity demand, would ease pressure on thermal power plants, the current data shows they are still functioning on a lower threshold of coal.

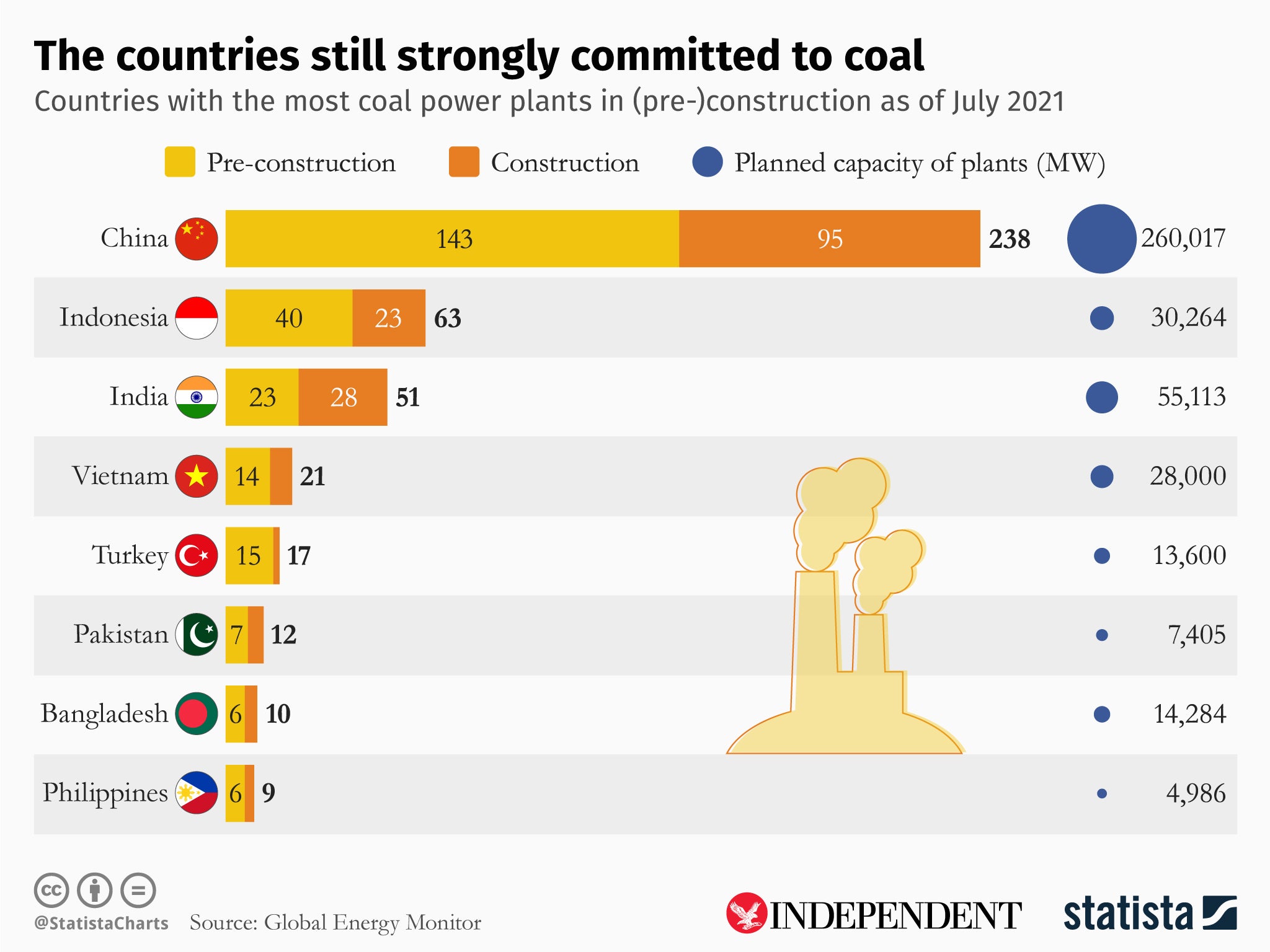

India is the second-biggest producer and consumer of coal after China and is home to the world’s biggest coal mining company, Coal India. India also has the world’s fourth-largest coal reserve, and its expected production capacity of already allocated coal blocks is about 20 per cent higher than the expected demand in the country by 2030, according to another CREA report.

However, the country faces a recurring power shortage every year that leads to blackouts during peak seasons, leaving residents and businesses in limbo. Recent analysis from experts hints that India’s recurring power shortage is a result of a larger supply chain problem that has less to do with its massive coal capacity.

In April, India witnessed an acute power shortage due to the unavailability of coal supplies, with more than 100 million units (MU) of energy shortage on eight days over the course of the month.

The power crisis in the country was a domino effect of several factors, including rising demand from industries after bouncing back from Covid, an increase in power demand for cooling solutions as March was the hottest in 122 years while the limited stock at coal power plants could not meet the demand.

However, the CREA report said that India’s recent power crisis was not due to coal production but “distribution and official apathy”, something energy experts in the country have been warning about for a long time. “The supply chain of coal is very vulnerable to the variability of power demand – due to heatwaves like the one in summer and variability of coal supply- rainfall causing logistical challenges in mining and evacuation of coal,” Himanshu Gupta, CEO of ClimateAi, told The Independent.

“However, the challenge is compounded by insufficient coordination of information between Coal India, the power ministry, Indian railways and various states,” Mr Gupta added. “More than the production or distribution flaw, I will call it a flaw of information coordination at three levels – forecasting of power, forecast of coal supply, and hence railway freight capacity required to evacuate that coal.”

India went through a power crisis during last year’s monsoon as well. The report points out that “the primary reason for the power crisis last year was the inaction of power plant operators to stock adequate coal before the onset of the southwest monsoon.” The report added: “The timing is crucial as the monsoon floods coal mines, hampering their production and transport to power stations.”

However, there is still no preparation in place for the upcoming season. What makes it worse is that the same mistakes are being repeated before the monsoon season, when the country is already aware of lowering stocks at power plants. At the start of May, non-pithead power stations had only six days of coal left, against the stipulated 20-26 days, the CREA report said. This amount is sufficient to power the country for only seven days, it said.

“India’s coal production this year was the highest in its history and, ironically, millions of people are left vulnerable to power cuts amid severe heatwaves and other vagaries of Indian weather,” said Sunil Dahiya, an analyst at CREA. “Officials also know very well that monsoons will impact mining and transport. Yet, no pre-emptive action was taken to resolve this crisis.”

However, the panic around the power crisis sent the Indian government to look for more ways to procure coal and expand its production further to deal with the shortage, at the cost of ignoring its climate goals. And even though the temperatures are scaling back to a normal level, thanks to early monsoon showers, it may still not bring the respite for power plants.

India’s coal minister, Pralhad Joshi, announced that India had increased its output by 6 per cent in April, compared to the same month in 2020. The government also rolled back a policy to cut thermal coal imports, and plans to reopen closed mines to address rising power demand.

The situation has led Coal India to issue a short- and medium-term tender next week to import coal. This is the first time since 2015 that the world’s largest miner will be importing fossil fuel.

“Heatwaves in India are a matter of life (people dying of heatstrokes) and livelihoods (more than 200 million Indians employed in agriculture and informal manufacturing depend on a reliable supply of electricity),” said Mr Gupta. “We can’t afford to have blackouts and hence the only short-term fix is to increase coal power production to increase the utilisation of existing coal power plants.”

However, he said he is not advocating increasing coal power capacity. “In the medium term, we should reduce the logistical and coordination challenges [and have] better forecasting systems to avoid such crises in the long run,” said Mr Gupta, adding that renewables and grid-scale storage can transition India’s electricity sector on a pathway that is clean, reliable and just.

An earlier report from CREA also warned against increasing the country’s coal capacity. It said that increasing coal production beyond what is required will lead to oversupply, creating financial stress and stranded assets.

Coal accounts for nearly 75 per cent of India’s power generation. The huge dependence India has on fossil fuel was a matter of concern at Cop26, where the country’s prime minister Narendra Modi made claims of reducing this burden, delivering half their energy from renewables by 2030 and hitting net zero by 2070.

However, none of those targets have been officially submitted as India’s new Nationally Determined Contributions to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change registry yet. In fact, it is still far from fulfilling its older goals despite huge progress in the past few years.

“Modi was the man of the moment at Cop26 with his commitments to scale up green energy and speed up emissions cuts. The six months since Glasgow have been a painful reminder of why it’s important for India to stick to these promises,” said Tom Evans, a policy adviser on climate diplomacy based in London with the think tank E3G.

“With more renewables and less coal, India would have a more diverse, resilient and secure energy system, and a less polluting one that can help avoid future devastating heatwaves,” said Mr Evans. “Coming forward with a clear and ambitious 2030 climate target is critical to making sure Modi delivers on his promises to accelerate the clean transition and would make him the star of the show at Cop27 once again.”

An analysis by think tank Climate Risk Horizons shows that India could have averted this power crisis if progress towards its old 175GW renewable energy goal had been on track.

“The additional generation from solar and wind would have erased the energy shortage and would have allowed power plants to conserve their dwindling coal stocks for evening peak periods when solar generation dips,” said Abhishek Raj, an analyst with Climate Risk Horizons. “The additional RE generation would have translated into a saving of at least 4.4 million tonnes of coal.”

In 2016, India set a goal of reaching 175GW of renewable energy by this year and, as of April, it had 95GW of operating solar and wind power. This implies a target slippage of about 51GW, the report noted.

“Two things are true: without the massive RE growth since 2016, the power crisis in April would have been much, much worse. At the same time, if we had been on track for 175GW by the end of the year, there would have been no power crisis at all,” said Ashish Fernandes, CEO of Climate Risk Horizons.

“Logistical constraints in the coal supply chain are a permanent feature and will certainly recur, as will heat waves; the best safeguard is to diversify our electricity mix. This reinforces the need for the centre and state governments to rapidly scale up their RE deployment and reduce dependence on coal,” he added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments