The Indian teenagers denied schooling and facing death threats because they wore a hijab

India’s Supreme Court is set to rule on an explosive case that has seen six Muslim teenagers banned from attending school because they wore a hijab. Arpan Rai reports from Karnataka

Aliya Assadi adjusts her teenage frame against the microphone to reach the right height as she speaks at the Town Hall building in the southern Indian port city of Mangalore.

“My hijab does not cover my brain; I can educate myself even if my head is covered,” Assadi, 17, tells hundreds of Muslim students and teachers.

She is one of a small group of Muslim teenagers who have not been allowed to attend school for seven months, simply because they refused to remove the hijab as demanded by the Hindu-majority government in the southern Indian state of Karnataka.

Since leaving her classroom at Udupi Government College on 28 December, she has not been back. And the case has simmered at both a local and a national level. It has now reached India’s Supreme Court, and a decision could be reached soon.

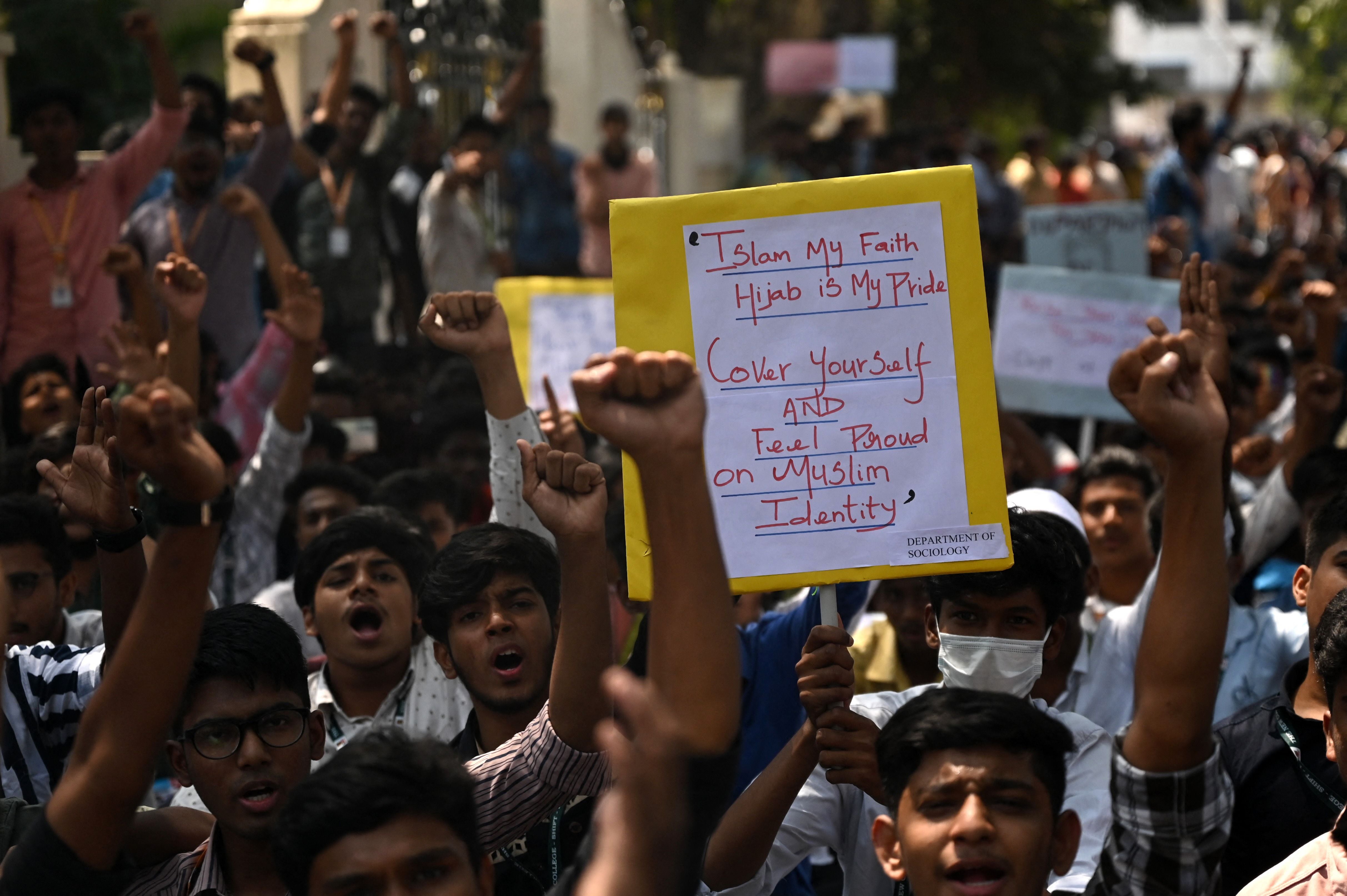

Karnataka has been embroiled in protests about head-coverings since last year, after six teenagers were refused entry to school because they were wearing hijab. Local authorities ruled that wearing hijab inside a classroom violated its school uniform policy.

Those six morphed into a protest of hundreds across the state, who filed a petition in court. The call of defiance reached most of Karnataka’s major centres, including the temple city of Udupi, and the lines were drawn for a battle that still rages today.

Why, the girls argue, should they not continue their education while wearing hijab, in the same way that Sikhism requires men to wear a turban, and Hindus must wear certain religious symbols such as vermillion on their foreheads?

The authorities have refused to back down, and presented the girls with a choice – remove the head-covering to return to their pre-university college, or side with religious practice and go elsewhere.

“Our stand is clear: our college was following uniform code for a long time, and these girls were removing hijab before entering their classes,” says Raghupati Bhat, who represents Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party in Udupi. “Inside the classroom, they can sit and follow the rules if they want education. Or else they should go to the schools where hijab is allowed.”

This mirrors remarks from Indian leaders who have said that Muslims should go to Pakistan if they are uncomfortable living in India.

But Assadi disagrees. “When we are born here, and are proven citizens of this country, then why are we being asked to authenticate our loyalties?” she asks. “The holy book of Quran says that modesty is a branch of my faith, and that hijab is an essential part of my religion. I am just carrying a branch of faith in myself. Why is that a problem for anyone else? I just do not understand,” she tells The Independent.

Karnataka’s High Court subsequently ruled that all religious symbols, including the hijab and the saffron-coloured shawls worn by Hindus, should be banned from classrooms, beginning the case’s journey to the Supreme Court.

This has meant that the girls have been out of school for far longer than expected, and now other institutions are refusing to enrol them.

Another of the girls, AH Almas, says: “Nobody is taking us. We are searching for admissions in new schools, and bracing to repeat our class all over again. But people are advising the school authorities, because they think we are a nuisance and will bring the controversy to their school premises.”

The local chatter, she says, is “Don’t take these six girls – please worry about the reputation of your college.”

Even if they are successful in finding a school, the process of transferring is not easy. To complete formalities such as signing the transfer certificate, the girls have been asked to remove their hijab.

“We have been told that to collect these final documents confirming our exit from this university, we need to remove our hijab to enter the premises,” says Almas’s friend, Hazrat Shifa, who is also a petitioner in the case. “I do not understand how a document’s signing is related to a piece of cloth covering my head,” an exasperated Almas adds.

The three have grown up together and forged a friendship from their early schooldays. But the battle over what they can and cannot wear in the classroom has exacted a heavy price. They have been stalked when they leave their homes, faced hostility from teachers, treated as pariahs, and even faced death threats.

“One evening, I was feeling terrible about having to fight this fight and reached out to my teachers, but when I opened the group chat, they had already left the group without a word,” Almas says.

She then went to check the private chat but found she was blocked from there as well. “We were shocked because we regarded them as our mothers. It was directly because they saw us fighting this, and decided to disassociate themselves from us. They think we did something wrong,” she says.

And this was just the beginning. “I cannot take the bus any more! It is the local transport we would frequently use to go around the town, but getting stalked and followed is more of a routine for us now,” says Assadi.

“Our security has been a huge issue. We cannot step outside the house alone; either someone would be waiting outside our house or someone would follow us,” Shifa tells The Independent.

The girls first noticed they were being followed in around January, when they saw the same person in every spot they visited.

“It is very obvious when people follow you. When we go somewhere, we see the exact same people looking at us,” says Shifa.

One day she was riding her scooter and became aware that she was being followed.

“To check if someone was actually tracking my way, I stopped on an empty stretch suddenly. I looked back, and the person following me also stopped. And then when I began, they also started their vehicle,” Shifa says. “It is now a frequent part of our lives, happening far more regularly than one can imagine,” says Almas.

Ironically, the hijab has at least prevented their faces from being identified, possibly helping to protect them from further problems.

Activists in the country have argued that the Hindu leaders and their loyalists are holding the fundamental rights of Muslim women hostage and jeopardising their education.

Almas, 18, says: “Education is totally separate from hijab and vice versa. It is my faith and a matter of belief. It is totally different; education does not ask whether the person pursuing it is wearing a hijab or not. Hijab does not cover my brain from receiving education and working.

“When the Indian constitution protects my right to get education irrespective of my religion, then who are some politically charged local elements to keep me out of the classroom?” she asks, adding that hundreds of girls now face the risk of having to drop out if they do not give up the hijab.

Several Hindu students have donned saffron scarves, stating that they will also flaunt their religion, but the girls have a response.

“If people want to wear whatever they want to school, sure, we do not have a problem. We are not getting disturbed by a piece of fabric,” Assadi says. “Our faith in Islam is not fragile.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments