Why must the United States persist with not allowing the unvaccinated through its borders?

Simon Calder answers your quetions on US entry requirements, the introduction of Etias and using ATMs in Greece

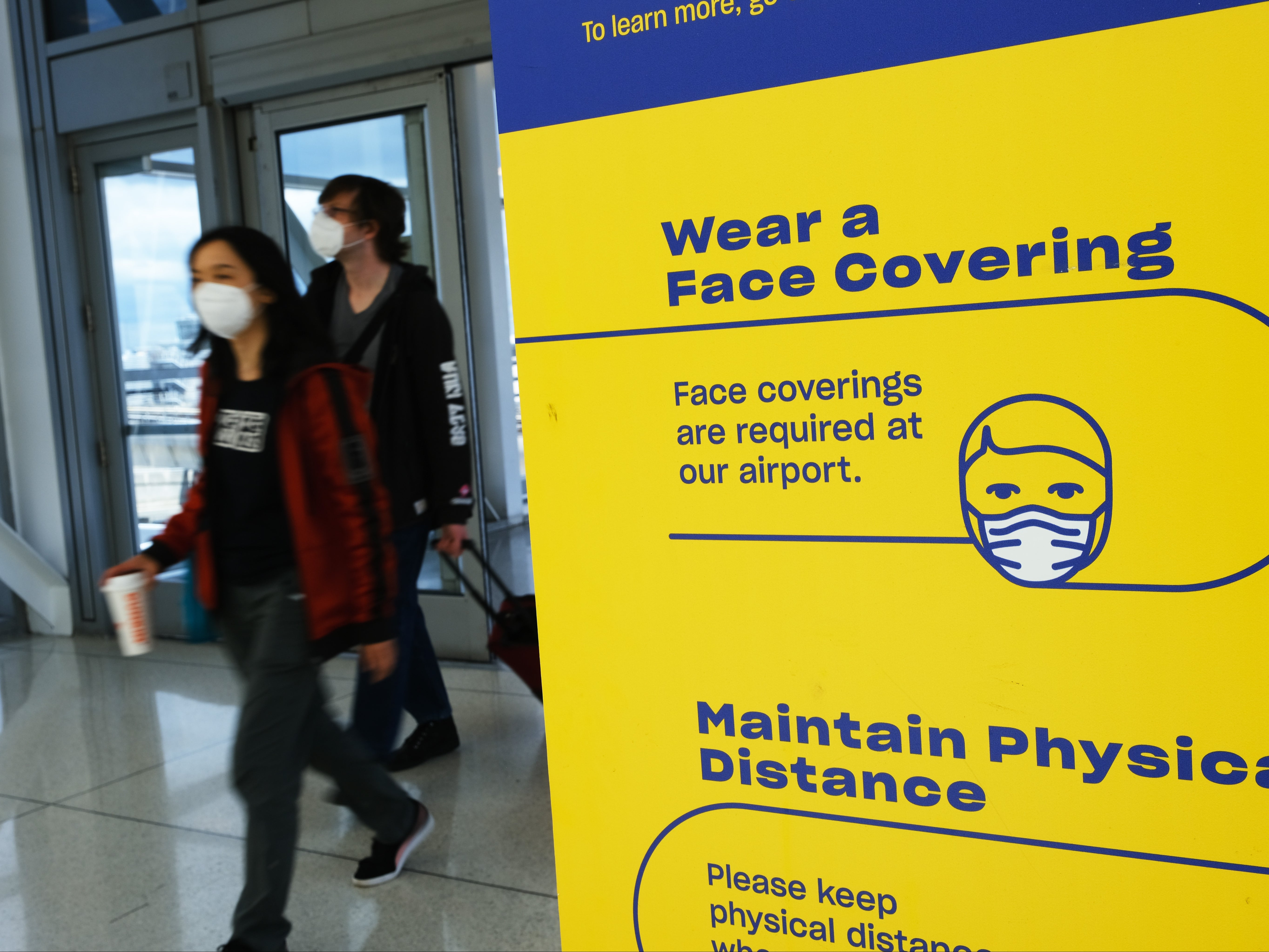

Q How come, when we know the jabs don’t stop people catching and passing on the virus, the United States still won’t allow the unjabbed in? Joe Biden has had four jabs and had Covid about three times. Where’s the logic? It’s not about our health, it’s all about politics.

Den

A The United States has chosen to be much slower in opening its borders to unvaccinated visitors than many other countries. Being double-jabbed is still mandatory (though a booster dose is not needed to meet this requirement).

The Centres for Disease Control (CDC), which is the US health regulator, firmly advocates the benefits of vaccination – saying they are “safe and are effective at protecting people from getting seriously ill, being hospitalised, and even dying”.

It says: “Getting a Covid-19 vaccine is a safer, more reliable way to build protection than getting sick with Covid-19. Covid-19 vaccines can offer added protection to people who had Covid-19, including protection against being hospitalised from a new infection, especially as variants continue to emerge.”

The CDC can argue that demanding visitors have vaccinations helps to ease potential pressure on the American healthcare system. At present, the rule is: “If you are a non-US citizen, non-US immigrant and not fully vaccinated, you will not be allowed to board a flight to the United States.”

That is not completely true, because there are some very rare circumstances in which travellers might be allowed in. But the CDC says: “Only limited exceptions apply to the requirement to show proof of vaccination.” The US was extremely quick to build barriers in response to Covid-19, and very tardy in opening – banning UK and European Union visitors for 19 months. I do not sense any great hurry to open up to unjabbed folk.

Q I am looking to drive Route 66 next year – September and October 2023. Car rental prices are currently very high but what are the prospects of them reducing over the next year?

Stefan R

A More on your choice of trip in a moment – but first, yes, I can confirm that car rental prices are already falling in North America. Last week in Quebec City, Canada, literally the only vehicle I could find ahead of time was set to cost me £300 for a two-day hire through Hertz. But a couple of days ahead, I checked again – and Avis had what I needed for just under £200. Still more than I would like to pay but definitely moving in the right direction. Fleets are building up, and with car rental companies also hanging on to vehicles for longer the post-Covid surge in prices is subsiding.

Because you will be travelling off-peak, I think you can happily wait until this time next year to finalise your rental plans – as well as your flight. I strongly recommend you book a fly-drive package, which I have successfully done multiple times through Trailfinders and British Airways Holidays. Good value, better consumer protection and fair treatment from the car rental companies in the US because they do not mess around the clients of such important companies.

Expect, though, to pay a drop-off fee of at least $300, probably payable at the end of the trip. You may be able to avoid it completely if you are able to secure a “driveaway” – delivering someone’s car for them as they move house. I have done this a couple of times but it is touch-and-go whether you can get a car where and when you need it. Your time will be limited, too, with probably only a week or so allowed from the Midwest to California.

Finally, Route 66 has an illustrious history. The highway was born on 11 November 1926, connecting Chicago on Lake Michigan with Santa Monica on the Pacific Ocean. But just three decades after Route 66 was created, a modern highway system was launched – with Interstate 40 superseding “the mother road” for most of the western portion.

What remains of Route 66 has many good aspects but a fair amount of the terrain is dull. My favourite stretch is between Victorville and San Bernardino in California, which you could easily access from either Las Vegas or Los Angeles on a two-day road trip. But I agree that’s not quite the American dream.

Q What will happen with stamping on passports when Etias is introduced next year? Will your passport still need a stamp on entry and exit? My passport is already half full and won’t have many pages left to stamp.

Jayne D

A The European Commission plans finally to implement its much-delayed European Travel Information and Authorisation System (Etias) in November 2023. The plan emulates similar systems created by the US (Esta) and Canada (Eta). The idea is that the authorities in the European Union and wider Schengen area have plenty of details about each traveller arriving from a third country and are better placed to make a decision about whether or not to admit them.

The UK, which was involved in the original planning for the system before the EU referendum, subsequently negotiated for British passport holders to be classed as third-country nationals. Therefore, UK travellers hoping to visit the Schengen area will be required to register and pay in advance for an Etias permit. On arrival at the border, you will also be required to supply fingerprints and a facial biometric.

One benefit, though, should be an end to passport stamping. At present, every British passport must be stamped on arrival in, and departure from, the Schengen area. This clunky analogue measure is required in order to detect any cases of overstaying. Another aspect of being third-country nationals is that British passport holders are limited to no more than 90 days in any 180 days. In practice, though, nobody checks: the process would simply take too long. Even the EU admits that passport stamping is “time-consuming, does not provide reliable data on border crossings and does not allow a systematic detection of over-stayers”.

Once Etias is running, it will operate in parallel with the European Union’s new “entry exit system” (EES): a Europe-wide database of who is coming and going. The idea is that each time a traveller crosses an EU external border, the system instantly registers the date and place of entry or exit. Think of it as having a passport stamped virtually: the EES database will keep track of the traveller’s movements across the frontier and identify cases of overstaying.

Until the system comes into effect, though, the stamping continues. Don’t worry about your passport filling up, so long as you are only travelling to Europe and back; EU frontier officials are required to provide an additional sheet of paper, if necessary, for the purposes of stamping.

Q I read your article about the very high fees being charged for using ATMs in Greece. In the Greek village where I stay, there is a message saying you will be charged €2.50 for each transaction. Is the “dynamic currency conversion” on top of this fee? I only use it once per holiday if I run short.

Karl K

A The coronavirus pandemic has accelerated the move towards plastic payments abroad, very often contactless. But in many locations – including Greek islands – cash is still king.

Increasingly, travellers pay the operator of the ATM a transaction fee for withdrawals abroad. This “direct access fee” is usually applied only to foreign visitors. The providers of ATMs say it is reasonable because, unlike in the UK, banks in Europe cannot subsidise the cost of cash machines through their other activities. Providing a fully stocked ATM on a Greek island, with all the security and maintenance issues involved, is an expensive business, and the transaction fee reflects this reality.

On your island there is probably no way to avoid the fee. But you can and should avoid “dynamic currency conversion” (DCC): in which the user is invited to lock into a specific exchange rate. Payment services providers are perfectly entitled to offer this option but they must show you in advance the rate they will apply. The invitation is usually something like: “For a withdrawal of €200 we can guarantee you a cost of £180”. This represents a very poor rate of £1 = €1.11.

If you do the sensible thing and say “I’ll settle in local currency”, there is an unknown at work: you do not know the rate at which your bank will convert the transaction. But I have yet to see a case in which DCC was a good deal for the traveller. The only circumstances in which I can see the option would be of value is for a business traveller wanting to keep a tally of spending in sterling. Unless someone else is signing off your expenses, always decline.

Finally, I think travellers need to get used to steadily rising costs for using ATMs abroad. Since the coronavirus pandemic, cashless payment has become much more common. With a dwindling market, providers are adding charges where they can to try to balance the books. So planning in advance and buying euros in the UK at a good rate is the way to go.

Email your questions to s@hols.tv or tweet @SimonCalder

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments