Lucy Worsley on how to solve history’s mysteries

In her latest BBC series, historian Lucy Worsley explores why puzzles from the distant past continue to fascinate us. She spoke to James Rampton about witches, the princes in the tower and whether George III was actually ‘mad’

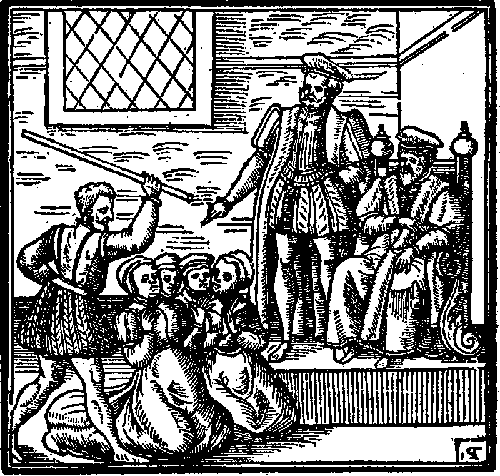

King James VI of Scotland took the divine right of kings to extremes. In a story that almost defies belief, he played an all too personal role in the zealous witch-hunting frenzy that swept 16th-century Britain.

In 1590, in preparation for acceding to the throne south of the border and becoming James I of England, the monarch was anxious to burnish his credentials as the upholder of the faith, so he supported a drastic new religious ideology which claimed the devil was recruiting women as witches.

That same year, a midwife called Agnes Sampson was arrested for leading a group of 200 “witches”, who were purportedly celebrating Halloween at St Andrews church in North Berwick.

The king believed reports that the women had conjured up the devil in the churchyard and held Sampson responsible for a near death experience he’d had. He thought that she had sacrificed a cat, attached male human body parts to its four legs and thrown it into the sea to whip up a storm that nearly killed him and his child bride as they returned from Denmark.

This was just one of the increasingly outlandish accusations that were being made against so-called witches at the time. The historian Lucy Worsley gives another particularly astonishing example. “According to the witch detection guide entitled Malleus Maleficarum, meaning The Hammer of the Witches, the worst thing witches were able to do was to use magic to remove men’s members.

“Once they had 20 or 30 of these members, they would keep them alive in a box or a bird’s nest. They would feed them oats, and the members would still be wiggling about. The witches would then have to decide whetherr to let the men have them back, which sometimes they did, and sometimes they didn’t.”

After her arrest, Sampson was transported in chains to Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh. There she was restrained with a device called a witch’s bridle, which involved four prongs being inserted into her mouth as she was fastened to a wall. She was completely shaved to reveal her “witch’s mark” and sadistically tormented for hours with a rope.

Then – if you can believe it – King James VI himself tortured Sampson. In complete agony, she gave up the names of 59 innocent supposed accomplices and was later strangled and burnt at the stake at Edinburgh Castle. At her execution, the priest declared: “The ungodly are not souls.” It was the start of a nationwide obsession with witch hunts. Over the next century, thousands of women fell victim to this state-sanctioned terrorism.

Very far from the cosy image of witches sporting pointy hats, broomsticks and black cats, the persecution of these women was an exceptionally brutal act of misogynistic tyranny powered by an overweening sense of piety.

The reason that witch hunting became heightened, more extreme, is because the Catholics and the Protestants were battling it out to be the godliest

Worsley explains why the monarch felt he had to be personally involved in the torture of Sampson. “He did it because he was so godly. I know it seems absolutely mad to us. But it was the mark of a good king to take this so seriously that he would get his sleeves rolled up and do it himself. He thought he was doing God's will. He was really building up the king points. But it does mean that today it’s hard to like James VI.”

The historian expands on why the self-righteous monarch was so driven in his pursuit of witches. “The act of hunting a witch was a virtuous thing to do that put you on the side of God. A common misconception is that Protestants were the only people interested in hunting witches because they were particularly godly. That’s not true. Catholics also hunted witches. Everybody hunted witches in the 16th century because it was the devout thing to do it.”

Worsley adds: “That just blows your mind when you think about it for the perspective of today. But the reason that witch hunting became heightened, more extreme, is because the Catholics and the Protestants were battling it out to be the godliest. Catholic or Protestant, the harder you hunted witches, the more likely it was that your religion was going to triumph over the other.”

The prevalence of witch hunting at the time is now being reassessed, though. Modern experts are re-evaluating events and concluding that witches were persecuted for reasons beyond religious zealotry. They also became such a fixation in 16th-century Britain because they were a very convenient scapegoat in a tumultuous era. “The explanation is economic,” says Worsley. “If there’s turbulence, if resources are short, if life is getting tougher – and this has happened in the pandemic as well – fear is expressed by targeting different groups and trying to blame them.

In the late 16th century, Worsley tells me, there was the Little Ice Age and there was an economic squeeze. It got so bad that there wasn’t enough land for everybody, resources were scarce, and people were going hungry. It’s in those conditions that you get people targeting outsiders. “In any time of stress, it is always somebody who’s a little bit different to the mainstream who gets blamed for it,” she says. “Of course, it was all heightened by the religious politics of the Reformation. That turned up the volume on everything.”

But unfortunately, witch hunts are not a thing of the past. “Why do people feel so strongly about witch hunts?” Worsley asks. “Because they are a boiled-down, concentrated version of injustice that we can still see in society today in the treatment of different genders. It is still happening in different parts of the world. Some people might also see themselves in these figures from the past. If today you were put into that box marked ‘mouthy woman’, you would perhaps feel an affinity with witches.

“Living in western Europe in the 21st century, we like to think that we are rational. But the world is not rational. There are many similarities between our world and the world in which people tortured women because they thought God wanted them to.”

The enigma of why a witch hunting craze gripped 16th-century Britain is just one historical mystery that Worsley examines in her new series. In Lucy Worsley Investigates, she explores why some unsolved historical puzzles continue to fascinate us and offers new explanations about why they took place.

We are still riveted by a whole panoply of unresolved riddles from our past. For instance, who really killed the princes in the Tower of London in 1483? What caused the Black Death? Was George III really mad? Worsley presents a new take on these infamous cases. She looks at these mysteries through a modern lens and shows how changing attitudes to children, gender politics, class, inequality, and mental health have provided fresh interpretations of these events.

“We are still fascinated by mysteries that happened so long ago because they are just not clear,” says Worsley. “Those are the things about history that go on being talked about, the things where there’s still an element of misunderstanding or confusion or doubt or a feeling that the story is not finished. And that’s why you never reach the end of the history book. There’s always something new to explore.”

She cites the example of the devoted band of Richard III aficionados who maintain his innocence of the murder of the princes in the Tower. “There are these people who are passionate supporters of Richard III, called the Richard III Society, and they’ve done some amazing research. It’s fabulous really that this topic, although it took place more than 500 years ago, is still getting people so excited.”

Key documents pertaining to the princes in the Tower were unearthed in 1934 and 1985. Who’s to say that there are not more out there as yet undiscovered that could still change the story?

The crucial point is that history is never set in stone. Emma Frank, the producer of Lucy Worsley Investigates, says: “History is not a fixed thing. It gets remade every time we tell it, depending on who’s telling it and what the world is like at that time. We have this dynamic relationship with our past, so we tell the stories that resonate with us now. That’s what history is for.”

It is evident, then, that there is no longer an “authorised version” of history. Worsley, who in her day job is joint chief curator at Historic Royal Palaces, observes that, “history is constantly being rewritten. This series is a very 2022 version of these stories. History just reflects what people are interested in in the present day. Looking for those connections between the present and the past is something that history is good at. I trust viewers to make those links and hopefully to be able to navigate the modern world better.”

We were really keen to put the victims back into the stories. What was it like to be one of the women caught up in the witch hunts? What if you look at it from her perspective?

Another aspect of historiography that has changed in recent times is the fact that historians no longer feel obliged to impose the “Great Man” theory on events. “We want to give the sense that history should reflect everybody,” says Worsley. “I have spent a lot of time in my career talking about kings and queens. I love them, everybody loves them, and they do get a lot of airtime. But history should not just reflect the experiences of the people who were in charge. Today we are increasingly interested in looking at history from the bottom up. But you have to work harder because the women we focus on in this series are not people who have left records.

“We wanted to give a worm’s eye view of these big, well-known events from history. What has shifted is the perspective. We try to tell the story through the eyes of the people who were powerless in that situation, like Agnes Sampson.”

Frank chips in that, “We were really keen to put the victims back into the stories. What was it like to be one of the women caught up in the witch hunts? What if you look at it from her perspective? What does that tell you? We wanted to give those people back their voices. We were looking for those hidden voices. I would love it if people came away from these films knowing the name of, say, Agnes Sampson.”

The four-part series also investigates if these incidents have been obfuscated by centuries of received wisdom. Our understanding of these events has certainly been shaped by timeless works of literature such as William Shakespeare’s Richard III, Alan Bennett’s The Madness of George III and The Daughter of Time by Josephine Tey.

In Frank's view, “It's interesting how certain images really stick. When you consider George III, what do you think about? The picture of him running down the path in his nightgown from the film The Madness of King George. That was the right way to tell that story at that moment. But it’s correct that it gets told again now, and no doubt it will be told again at some point in the future.

We can’t understand anything about the present, or indeed the future, without first understanding the past. Worsley reflects on the importance of studying history. “The first reason why anyone should be interested in history is that it’s fun and enjoyable and fascinating. If that’s all you want out of history, that's fine with me. I don't expect people who come to Hampton Court Palace to want to know about the politics of the Reformation or the aesthetics of the buildings. I’m very happy for them to have a nice day out with their family and eat some cake. That's enough.

What does Worsley hope that viewers will take away from her series? “Trying to bring history to a wider audience and make them engage with the wonder of history is the joy of my life. I see myself as the thin end of the wedge. If you have a nice hour on the sofa with me, at the end of it my ideal result is for the viewer to think, 'OK, I need to know more about this now. What will I do? I'll read some books about it'.”

She adds, “The best thing that ever happens to me is when I get a letter saying, ‘I watched one of your shows, and I got into the subject. I read some books, and then I did an evening class. Then I went to the Open University and did a history degree. Now I’m qualified, and I want your job’. That's great. I would be very happy to build in my own obsolescence like that. That’s what I’m here to do.”

Lucy Worsley Investigates begins at 9PM on Tuesday 24 May on BBC2.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments