Canoe man is one of those stories you just couldn’t make up

For the programme makers, the story of John Darwin was the gift that just kept giving – a story where fact was definitely stranger than fiction. James Rampton talks to them

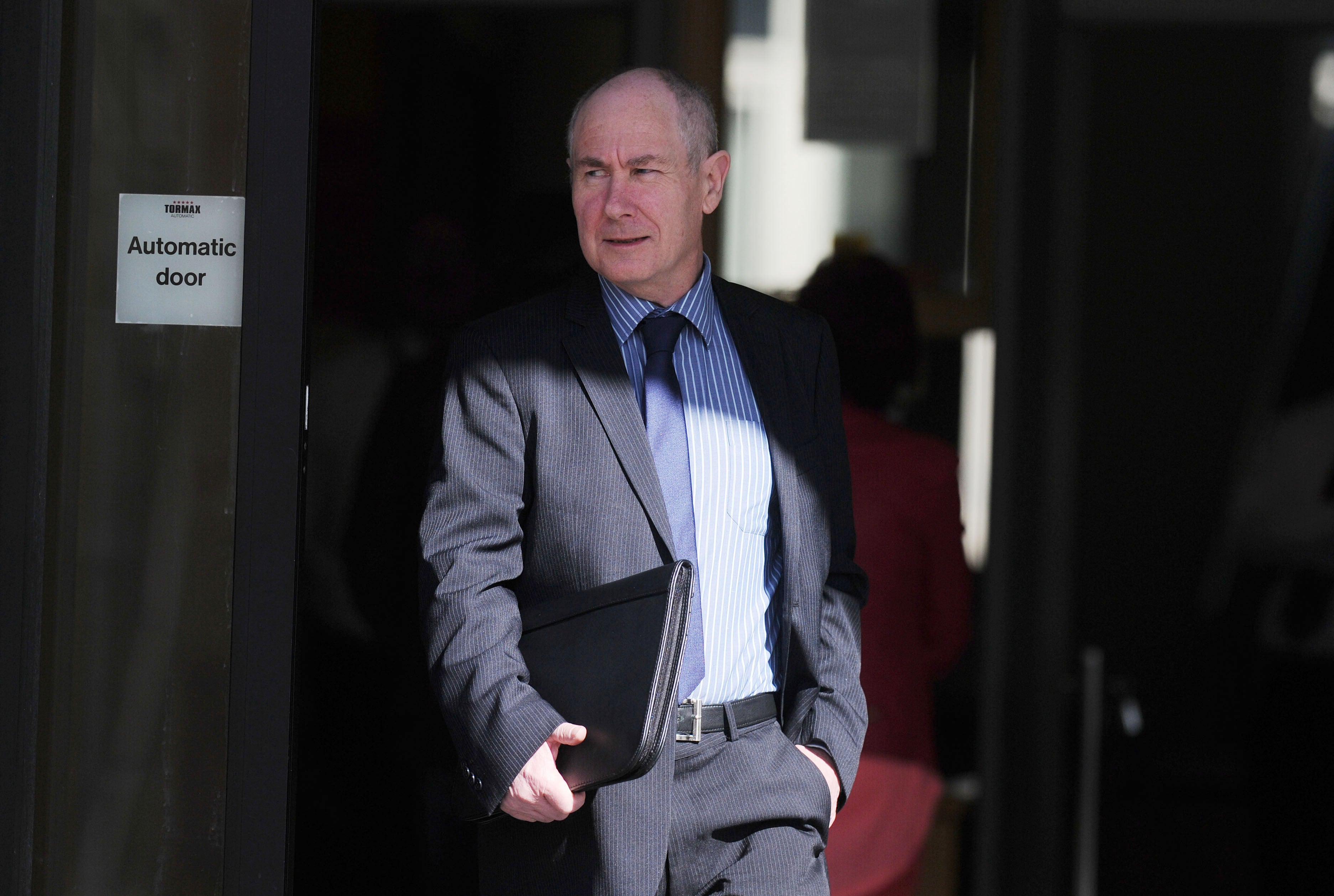

Even now, 20 years after it began, the story of John Darwin, the so-called “Canoe Man”, sinks all attempts at credible explanation. It simply defies belief. The tale of John – who in 2002 faked his own death in a canoeing accident, got his wife Anne to brazenly lie to their two sons Mark and Anthony that he had died, and hid in the bedsit next-door to the family home before being rumbled five years later – epitomises that well-worn phrase, “fact is stranger than fiction”.

The writer Chris Lang, who has turned the Darwins’ story into The Thief, His Wife and the Canoe, a riveting four-part drama that starts tonight, emphasises that it was this unbelievable quality that initially drew him to this yarn. “The ‘fact is stranger than fiction’ aspect was the first thing that I thought of as I was turning the opening page of the research.”

As he started reading this incredible story, he recalls: “It just kept on delivering incredible twists and turns. It was like a very, very twisted fairytale. There is something very ‘other’ about the Darwins’ world.

“Right at the beginning, I said, ‘if I had pitched this as an original story, then everyone would have said, ‘Don’t be absurd! What are you thinking? This could never happen. No one would ever believe these characters, and no one would ever believe that any of these things happened.’ And yet they did. That’s the extraordinary thing about this story.”

Dave Nath, the executive producer of The Thief, His Wife and the Canoe, weighs in that he too was attracted by the scarcely plausible nature of the tale. “What makes this story even more bewildering is the nature of the two people at the heart of it. They feel so ordinary that you wouldn’t bat an eyelid at either of them if you saw them in the street. It stretches belief that plans of such staggering ambition were being conjured up by ordinary people behind the net curtains.”

He continues: “One thing that stands out for me is the fantastical quality of the story. For instance, at one moment a man who is ostensibly dead is listening on the other side of the wall to his sons talking about their deceased father. This story is the gift that keeps on giving.”

John was in appalling debt. A poorly paid prison officer, he had horribly overextended himself. While he owned 12 properties, he owed an eye-watering £64,000 on 13 different credit cards

This yarn certainly has it all; as well as the fairytale element, it also has many germane things to say about such topical subjects as toxic masculinity, coercive control and the power of forgiveness. But one crucial question remains: what on earth drove the Darwins to concoct – and nearly get away with – this totally outrageous plan? For a start, John was in appalling debt. A poorly paid prison officer, he had horribly overextended himself. While he owned 12 properties near their home in Seaton Carew, Hartlepool, he owed an eye-watering £64,000 on 13 different credit cards.

Too proud to declare himself bankrupt, John instead hatched this ludicrous plot to stage his own demise, get his wife to tell their two sons their father had been lost at sea and claim hundreds of thousands of pounds in life insurance. The scheme was so far-fetched, it almost succeeded.

John was propelled by a ridiculously puffed-up sense of his own status. A good example of this was the fact that he spent £3,000 on a personalised number plate for his Range Rover before he had even got the gas connected to his new house.

“John came from a very humble background,” says Lang, “and that was part of what motivated this desperate desire to be seen as more successful than he was. There was a big disconnect between his sense of place in the world and what it actually was.

“He was a man who wanted to drive in a Range Rover with personalised number plates, saying, ‘look at me, aren’t I doing well?’ When people have a personalised number plate, it perhaps says more about them than they intend to. I don’t think any of us has ever seen a car with a personalised number plate and gone, ‘cool, I wish I was him!’”

Nath takes up the theme. “John had a grandiosity and a real sense of ambition and ego. That meant that he always came first. The best example of that is that he used to go around telling people that he’d be a millionaire by the time he was 50. But the reality was that he was facing bankruptcy by the time he was in his early 50s.”

John also had an inflated view of his own intelligence. “He thought he was cleverer than the police and the insurance companies,” Nath carries on. “His ego was out of control. When that happens, you might come up with a fanciful idea that you think you can get away with. And to be fair, he almost did.”

In addition, John personified the very current idea of toxic masculinity. The actor Eddie Marsan, who portrays John in the series, jokes that this character is just the continuation of a misogynistic seam that has run throughout his career. “I have played the husband of Olivia Colman, Shirley Henderson and Sally Hawkins and abused them all! I’ve abused all the great actors of our generation!”

With a laugh, Marsan adds: “Toxic masculinity is what I do. When I did Tyrannosaur [a shocking 2011 film about a brutal wife-beater], that character was at a comfortable distance from us. We could look at him and it wasn’t us. But now, post MeToo, the abuse is more nuanced and subtle. It’s not just violence, it is psychological manipulation. Society is trying to work out how to deal with men and their narcissism and toxic masculinity.

“Young men are encouraged to believe in the myth of their own omnipotence and think that they can do anything. But reality shows that we can’t, and some men can’t deal with that. So they become deceitful and liars and narcissists. That’s what we’re seeing in our politics, in our marriages, in all our institutions. John is an embodiment of all that.”

It is that narcissism which also underpins John’s unspeakable cruelty towards his sons. Nath outlines why the father was so unimaginably callous towards his own offspring. “John was able to compartmentalise everything he did, and was able to do things almost regardless of their consequences.

“He saw himself as an island. He didn’t see the rest of the world and the impact of what he did beyond himself. It’s a strange character who is able to walk away from problems and their legacies and just move on to the next thing. But that speaks a lot about the personality we’re dealing with in John.”

Lang chimes in: “John lacked any empathy as a human being. Clearly, throughout his life, he displayed very little sense of care for other people. He showed that in his response to Anne when he first posited his plan to her. She said to him, ‘What are you thinking? What about our family? What about our kids? What do you think it will do to them to think that you’re dead?’ And he genuinely responded by saying, ‘Well, I think they’ll be upset for a few weeks and then get over it.’”

The writer continues: “That’s such an extraordinary thing for a father to say about his children because who could ever think that would be their likely reaction? Only someone who themselves is emotionally extremely stunted, and has a very shallow well of emotional reserves, who has very little ability to empathise and to connect and understand how other people might feel. So that’s how I think he rationalised the fact that he was desperate and needed to get out of a financial hole.”

He didn’t see the rest of the world and the impact of what he did beyond himself. It’s a strange character who is able to walk away from problems and their legacies and just move on to the next thing

The Thief, His Wife and the Canoe also touches on the very relevant topic of coercive control. John had been a domineering influence over Anne since they were teenagers. He used to say: “The only time I would take my wife out is to vote.” What a charmer.

After he and Anne had finally split up, he sent her a deeply disturbing photo of her with a copyright sign stamped on it. It said, “You can run, but you can’t hide. I still own you.”

John’s malign hold over Anne began on the school bus when he was 16 and she was 14. He deliberately knocked off her school hat and laughed at her derisively in front of all her fellow pupils.

Lang admits: “It might seem a very inconsequential and light hearted moment, but it says a lot about a person that the way you attract someone else’s attention is through an act of ridicule. We ignore that part of a coercive relationship at our peril because from that moment on I think Anne had no agency in her life at all.”

Nath reveals that when he and Lang found out about the incident on the school bus, “the penny dropped in terms of why he might have done this unforgivable thing. It became emblematic of the way he treated her. The die was cast in the power relationship of their marriage. From that moment on, Anne played second fiddle to John and had no voice in the relationship. He felt he could do that to her, and it seems to have become the pattern in their relationship. It feels pivotal.”

John used those same dictatorial techniques to bully Anne into agreeing to his crackpot plan. When she was wavering, he exploited her innate sense of insecurity by sneering: “No one is queuing up for a woman like you, Anne.”

She didn’t have any social life at all. Her life was her husband and her boys. She endured years of feeling invisible and powerless

He continued to mercilessly tap into her inferiority complex. “Here was a man who was very dominant and controlling, very confident of his own opinion,” Lang says. “That shaped her. She didn’t have any social life at all. Her life was her husband and her boys. She endured years of feeling invisible and powerless.

“Anne often talked about how at a certain stage in their marriage she gave up ever arguing with John because he would always get his own way, so what was the point? They married young – I think she was 21 or 22. Three decades of that kind of marriage does something to you.”

The writer of the drama, which might have been subtitled, “Darwin: The Evolution of a Fraudster,” carries on: “She went through years of being made to feel inadequate and a nobody. She had a terrible fear of being left alone. If you have had decades of your husband telling you, ‘You’re nothing, you’re only defined by your association with me,’ that’s a very potent fear.

“If you’re a 50-year-old woman and thinking that no one else would have you, you’re looking at a life of loneliness and financial hardship. Those are very real fears, and John played on them to get Anne to do what he wanted. She absolutely went along with his plan because she was under his control in many insidious and complicated ways.”

Nath expands on how John was able to manipulate his wife throughout their marriage. “She had lost all sense of her own identity. She lacked a voice in that marriage. She seems to have been so subsumed by this man that she went along with something that in hindsight was unthinkable.”

In 2007, the couple was finally brought to book, thanks to a typical instance of hubris. Thinking they had got away with their crime, they moved to Panama, where they aimed to start an idyllic new life in a luxury flat. However, blinded by their own arrogance, they made a fatal error. They assented to be photographed by the estate agent in their glitzy new property. An eagle-eyed citizen in this country spotted the picture of the supposedly dead John on the internet and reported him to the police.

Amazingly, even then John, who feigned amnesia on his return to the UK, might have managed to evade justice. Lang says: “I’ve been asked many times, ‘If that photo hadn’t been found, do you think they would have got away with it?’ And I think it’s very, very possible that they would.”

But they didn’t. The Darwins were arrested in December 2007. Anne lamented to the police that “my sons will never forgive me,” while John showed no contrition whatsoever.

He wrote a terse 10-word note to his ailing father. Lang recalls: “The note basically said, ‘Dear Dad, don’t worry about me. I’m absolutely fine, John.’ It’s comically appalling. Again, it’s that solipsism. It’s all about him, and nothing to do with how his very frail 91-year-old father might feel about what his son had done to him as well as to his own sons. There’s no sense of empathy, no sense of care. I don’t think that relationship ever recovered.”

On 23 July 2008, John and Anne Darwin were both found guilty of fraud. John was sentenced to six years and three months in prison. Meanwhile, Anne, whom the police called a “compulsive liar”, was handed a sentence of six years and six months.

She was subjected to a lot of abuse in the press. “It’s a story that excites a very strong reaction,” Lang muses. “When a mother, especially, does what Anne did to her two boys, it hits a particular nerve. People have very strong feelings about it.”

Ironically, it was only when Anne was jailed that she began to feel liberated from John’s tyranny. “Once they were separated by being in prison, Anne had some space for the first time,” says Nath.

“The constant noise of John had gone. She was able to make a decision clearly for the first time, which was, ‘I don’t want to be with him anymore because his influence is unhealthy and detrimental.’” She went on to take out a restraining order against John and divorce him.

You neutralise acid with an alkaline of kindness. The sons have made something rather beautiful out of something deeply toxic and tragic and shameful

Which brings us to the only uplifting part of this whole sorry saga: the fact that Anne sought – and was granted – the forgiveness of her two profoundly wounded sons. For his part, John never made any effort to repair his relationship with his sons and has moved to the Philippines with a new wife.

For Lang: “It’s a story about the potency of forgiveness because the most important thing is that Anne’s sons forgave her. That was really key right from the beginning. We see enough really deeply bleak, sickly true-crime stories. I was really struck by the fact that Anne rebuilt her relationships with her sons in a way that John didn’t.

“That’s really the point of the story: the power of compassion. You don’t get compassion unless you try and extend empathy and understand why people do things. Good people do bad things. Let’s try and understand Anne. Let’s try and forgive her because if her sons can forgive her, I would hope that we can as well.”

The writer adds: “You neutralise acid with an alkaline of kindness. The sons have made something rather beautiful out of something deeply toxic and tragic and shameful. They rebuilt their family.”

Nath agrees: “If we can’t forgive, where does that lead us? To a place where we’re all forever in conflict. The most unforgivable emotional betrayal has been committed. And yet Anne’s sons find it within themselves to forgive their mother. Because of that, it feels redemptive and very moving at the end. You realise how huge a chasm it was for the sons to cross and how many people would never have been able to forgive in those circumstances. It’s really inspiring.”

The makers of The Thief, His Wife and the Canoe sum up how audiences might react to their drama. In Nath’s eyes: “It does raise a question about the nature of control and power and coercion within marriage, and maybe some people who are watching might start to recognise themselves.”

Marsan concurs. “I think there might be a lot of divorces after people have seen it! I think a lot of married couples might turn to each other and go, ‘That’s you!’”

What has become of John, then?

In April 2014, it was said that John had given back just £121 of the £679,073 which the judge had demanded that he return. The last report of him was on 28 March this year when his new wife Mercy Mae Avila Darwin told the press that her now 71-year-old husband was off to Ukraine to assist in its war effort against Russia. She added that he had good life insurance, which was “good for me”.

Eight days later, however, John was photographed not on the frontline in Ukraine, but pottering around doing the shopping in his new home town of Antipolo in the Philippines.

You couldn’t make it up.

The Thief, His Wife and the Canoe begins at 9pm on Sunday 17 April on ITV

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments