With true crime, the truth is stranger than fiction

Why do especially striking crimes continue to fixate us and why have they inspired writers to create some of their most memorable work? James Rampton finds out

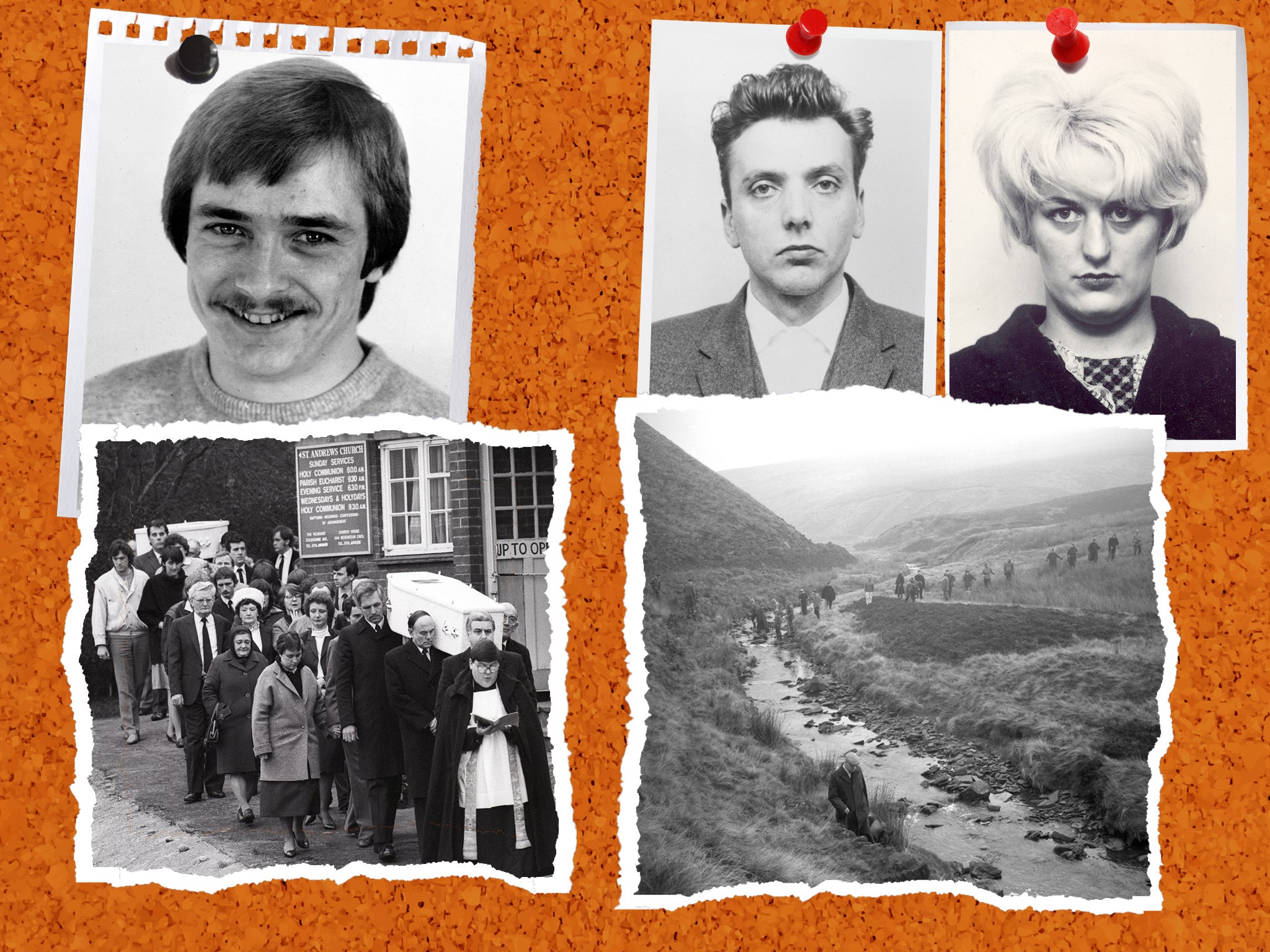

Mark Billingham’s blood ran cold. A few years ago, the acclaimed crime novelist was working on Couples who Kill, a documentary about the Moors Murders, the notorious killing of five children between 1963 and 1965 by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, when out of the blue he received an unsolicited letter at his home address. As he read it, Billingham shivered with horror. It was from Brady himself.

“I was absolutely staggered,” says the novelist. “My wife did not want to have the letter in the house. That is my primary memory of that moment; when I said to her, ‘Look at this’, she just went, ‘Get rid of it, get rid of it!’.

“It was a very odd letter. Firstly, just the way it looked. We had a forensic psychiatrist working on that programme, and he said, ‘Even if I didn’t know who this letter was from, if you covered up the name at the top, just looking at the tiny little scrolled writing, running over hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of lines, I could tell you the person who wrote it had an issue’.”

Billingham goes on to reveal what was in the letter. “Brady wanted to tell me firstly how badly he was being treated. It was hard to know how to react to that, but it echoes the kinds of things you see in films about Hannibal Lecter. He wanted me to know how clever he was – literally what his IQ was.

“And it had the most bizarre sign-off. The last words were: 'The ball is yours.' I still think about that sometimes. I don't quite know what he meant by that or what he was expecting me to do. But yes, it was certainly the strangest letter I have ever received.”

The 60-year-old novelist, who was inspired by the Moors Murderers to write his bestselling 2017 book, Their Little Secret, is swift to add that he was never tempted to reply to this most disturbing of missives. “Brady was criminally insane, and I knew there was nothing whatsoever to be gained from entering into correspondence with somebody like that. I didn't want to go there. I simply write about fictional versions of these characters – it's far safer that way!”

The popular crime novelist Peter James had a similarly chilling encounter with a murderer who became the subject of a widely read book. The author became fascinated by the so-called Babes in the Wood double murder that happened in his home city of Brighton. On 9 October 1986, two nine-year-old girls, Nicola Fellows and Karen Hadaway, vanished. Their bodies were found the next day in Wild Park, Moulsecoomb. The following year, the prime suspect, local roofer Russell Bishop, was tried for the murders and sensationally acquitted.

That is when James first saw him. “It was around the time I was just starting to go out with the police and get research help from them, so I had a little bit of insight into the Babes in the Wood case. I knew that the police were all 100 per cent certain Bishop was going down. For them, there wasn't a shred of doubt.

“I remember one day I was in central Brighton in a place called Churchill Square. I was about to cross the road when I heard this fanfare and blaring music, and I saw a carnival float. It was a flatbed truck with this guy standing on the back going, 'Yeah, yeah, yeah!' It was Russell Bishop, and it was the day after he’d been acquitted. There was a big banner down the side of the truck, which read, 'Russell Bishop free!' He was literally saying, ‘Look at me, I’m free!’ I just thought, there are two little girls who are dead. Whether you’ve been freed or not, that does not give anybody the right to be prancing through Brighton celebrating. There is nothing to celebrate about this. And that’s what began my fascination with this case.”

In the documentary, we revisit the terrible crimes that Hindley and Brady were guilty of, and they should never lose their power to shock

On 4 February 1990, Bishop abducted a seven-year-old girl known as “Claire” (not her real name) at Devil's Dyke in East Sussex, and locked her in his car boot. He indecently assaulted her, before she managed to escape. In December of the same year, he was convicted of the kidnapping, indecent assault, and attempted murder of “Claire”. He was handed a life sentence with a recommended minimum term of 14 years.

Then, after the double jeopardy laws were altered in April 2005, the Babes in the Wood case was reopened. In 2018, a full 32 years after committing the offence, Bishop was finally found guilty of the murder of Nicola and Karen and sentenced to life imprisonment with a recommended minimum term of 36 years. The investigation into the case is the biggest and longest-running inquiry ever held by Sussex Police. Bishop died in prison of cancer in January of this year. His despicable crime prompted James to write his widely praised 2020 book, Babes in the Wood.

The Moors Murders and the Babes in the Wood stories are just two of the cases that feature in a new TV show, Once Upon a True Crime. In this four-part series, four leading crime novelists explore why some especially striking crimes continue to fixate us and why they have inspired these writers to create some of their most memorable work.

In the other two episodes, Denise Mina examines the case of one of Scotland’s most notorious serial killers, Peter Manuel, which provided the inspiration for her novel The Long Drop, and Douglas Skelton investigates the brutal Ice Cream Wars, a tense gangland turf war in 1980s Glasgow that influenced his novel Blood City.

James, who was also written a series of global bestsellers about the work of DS Roy Grace, explains why, many decades after they took place, these iconic cases still have the power to horrify us. “I am always fascinated by what is the difference between someone who can commit a horrific crime and you and I. Is there a difference? We like to think that we'd never do that, but just how close are any of us to doing that? That's one thing that's always gripped me about true crime. In fiction, we make we can make stuff up, but the truth is stranger than fiction.”

Billingham affirms that the heinous nature of these crimes does not fade as the years pass. “In the documentary, we revisit the terrible crimes that Hindley and Brady were guilty of, and they should never lose their power to shock. They should always be profoundly shocking. Hindley and Brady have become these almost mythical figures, the absolute personification of evil. It's something that we're just stuck with.”

I am always fascinated by what is the difference between someone who can commit a horrific crime and you and I. Is there a difference? We like to think that we’d never do that...

To illustrate the point, Billingham adds: “One of the many fascinating documents I came across was a letter from the then Home Secretary Leon Brittan about possible parole for Hindley. The then prime minister Margaret Thatcher had written across the top of it: 'She gets parole over my dead body. These crimes are way too horrific. She should never be released.' I'm not sure that has happened very often in legal history.”

Another reason why these particularly hideous crimes remain in the public consciousness is because, thank goodness, they are relatively rare in this country. “We are fortunate in the UK that we have very few serial killers,” says 72-year-old James. “In the United States, the police recognise that something like 50 serial killers are active at any one time. It used to be that in America, they didn't have a national fingerprint database. The UK was years ahead of them in having a national DNA database. America also has all these different privacy laws in different states. So it’s very easy for someone like the serial killer Ted Bundy to move across different states and offend in one state and then another without a link. Here in the UK, that's much harder.

“Because we have very few serial killers, when it does happen, it becomes a massive focus of attention. So cases like the Moors Murderers, Fred and Rose West and Steve Wright will continue to fascinate us. I think it's important that we do remain aware of the fact that there are people out there who are capable of doing these things.”

Some crimes carry on reverberating, too, because the perpetrators are fiendishly adept at attracting publicity. Brady is a very good example of that. Billingham, who is responsible for the very successful Tom Thorne cycle of novels, recollects that: “During the making of Couples Who Kill, the producers had written to Brady in the hope of securing an interview with him. But I have to say, I’m very glad it never happened. I'm very pleased I never got to sit across the table from him.

“Having spoken to people who did have long relationships with Brady, they all told me, 'You do not want that man in your head. He is an arch manipulator'. Later I did write about him and Hindley in Their Little Secret. Inevitably, then they are in your head, but you don't want them there for very long. You want to be able to switch them off.”

In recalling these dreadful crimes, however, there is one person above all who should never be overlooked: the victim

Brady, who died in prison in 2017, certainly proved extremely skilful at manipulating the press. The murderer, who with Hindley was the subject of films such as See No Evil: The Moors Murders and Longford and songs such as The Smiths' Suffer Little Children, was the master of bending journalists and campaigners to his will.

“What fascinated me,” Billingham says, “was that just before making Once Upon a True Crime, I read an amazing article about just how close Brady and Hindley came to being executed. Capital punishment was only abolished a month after they were arrested. That meant they were the first criminals of their kind to go into the prison system, and the prison system did not know how to handle people like them.”

Sentenced to life, the pair became highly skilled at remaining in the public eye even when behind bars. Astoundingly, they were permitted to write letters to journalists and supporters in the outside world. Brady in particular was very quick to exploit this unprecedented freedom. “There's no question, Brady was incredibly smart,” Billingham observes.

“He was a very bright guy. Unlike Hannibal Lecter, he didn't speak dozens of languages and eat fava beans with a nice Chianti or anything like that. But when he was inside, he had a way of getting inside people's heads and really manipulating them. He was able to play games with really experienced professionals, not just within the prison system, but psychiatrists and solicitors, too.”

Going into prison in 1966, Billingham continues: “Brady was the most famous person in the whole place, and he played up to that. Very early on, he learnt how to get what he wanted. There was a lot of sham and nonsense with him. He was never on the famous hunger strike he talked so much about. He said he was starving, but he was saving up Creme Eggs and Mars Bars and stuffing his face with them when nobody was looking. He could really put on a show. He loved attention. He would have absolutely loved Once Upon a True Crime.” Thank the Lord, then, that he is no longer around to gloat about being the centre of attention once again.

The novelist carries on that in watching Once Upon a True Crime, “viewers will understand the role that the media played in this ludicrous relationship between the two prisoners that went on for so many years after they were both behind bars. We were all complicit in that we allowed that to happen and allowed them to game the system. I hope people are as shocked as I was by quite how easily manipulated a lot of people in the penal system were and how Brady and Hindley got away with so much.”

This show is just the latest programme to feed our current fascination with true crime. James, whose office is decorated with a fetching array of police hats from all over the world, reflects on why we are so fixated by it. “When there's a bad accident on the motorway, everything slows down on the other carriageway to look at it. People are thinking, ‘How did that happen? How can I make sure that never happens to me?’

“I would say exactly the same about true crime. Part of what's going on when we read or watch true crime is that we are saying to ourselves, ‘How did the victim get in that situation?’ We are genetically programmed to survive. There is a deep thing going on at a subconscious level where we want to learn by finding out about these horrible crimes. We want to see what messages we can take away that could help us survive.”

In recalling these dreadful crimes, however, there is one person above all who should never be overlooked: the victim. Billingham asserts: “I hope that alongside the names of Hindley and Brady, the names of their victims, Pauline Reade, John Kilbride, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey and Edward Evans, will really register with people. I hope people will also understand how awful it is for Keith Bennett's family that his remains have not been recovered.”

James echoes this. “When children are involved, that really lingers. The Moors Murders, for instance, will continue to fascinate us. It's important that we remain aware of the fact that there are people out there who are capable of doing these things.”

But we must also never lose sight of the fact that, “all crime inflicts trauma. I was burgled a few years ago, and we ended up moving house because it felt dirty afterwards. I know someone whose husband was just beaten up outside a park, and now he can't go out at night anymore because he's too scared. In the same way, it's almost impossible to get one's head around what kind of damage being locked in the boot of a car does to a human being.”

James concludes: “It’s absolutely vital that we remember the victims. They can get forgotten in all this. I asked one of the detectives involved in the Claire case how she was later in life, and he replied, ‘Not great’. Even though she was very plucky and gave valuable evidence against Bishop, the impact of what he did meant she continued to suffer trauma. I've talked to adult rape victims in my research over the years, and I’ve heard the same thing from a number of them.

“One of them told me, ‘You never get over it. It's like having your soul murdered’.”

‘Once Upon a True Crime’, 9pm on the Crime + Investigation channel on Mondays, is available to stream on CI Play

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments