‘It will take years for wages to recover’: How long can we expect the cost of living crisis to last?

Real wages are falling at a record pace, with worse yet to come according to financial analysts. Ben Chapman asks whether there is any hope of a let-up

It may take years for real earnings to recover to their previous peak, experts have warned. Huge increases in the cost of gas, electricity and a host of other basic goods have sent inflation rocketing to 10.1 per cent, with little sign that it is slowing down.

Families on lower incomes have been hit even harder, with consumer price inflation for the poorest tenth of households hitting 10.9 per cent, compared to 9.4 per cent for the richest tenth of households, according to calculations by the Resolution Foundation – a “cost-of-living gap” that the think tank says reflects the fact that less well-off households spend a greater share of their budget on food and energy bills.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year, starting a protracted war, has certainly contributed to the current turmoil afflicting global energy markets.

Price rises are far exceeding wage growth, and worse is yet to come this winter. But for how long might the squeeze last, and how far could living standards fall? We asked the experts.

‘Years to recover’

“Wages are set to lag inflation for a considerable period,” says Sarah Coles, senior analyst at funds supermarket Hargreaves Lansdown.

She points out that the Bank of England expects real post-tax income to end the year having fallen 1.5 per cent; that it will drop more sharply in 2023, by 2.25 per cent; and that it will rise by 0.75 per cent in 2024. It is likely to take years for wages to recover to where they were at the start of this year.

Coles adds: “We suffered over a decade of lower wages in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. In fact, wages only returned to their pre-crisis high point just before the pandemic struck.

“However, this was during a time of low inflation, so the impact was felt differently. If you stayed in work, while pay rises were thinner on the ground, prices weren’t racing away, so it didn’t rapidly get more difficult to make ends meet. This time, huge hikes in the cost of essentials are making life more difficult by the day.”

Coles expects the impact of the invasion of Ukraine on the gas supply to weigh heavily on the energy market for as long as the conflict lasts – with knock-on effects for the cost of electricity produced by burning gas.

“At the moment, analysts are predicting that the energy price cap will keep climbing for the rest of the year and only start to fall back in July 2023, but forecasting so far out in an uncertain environment is an inexact art,” she says.

The cap on the price households pay for electricity and gas is currently set at £1,971, but consultancy Auxilione has predicted that the cap on bills will gradually rise by more than £4,000 over the next eight months. Their latest analysis expects the cap to reach £3,576 in October, rising to £4,799 in January, and finally hitting £6,089 in April. The new forecast is an increase of £96 in January and £233 in April compared to the consultancy’s previous estimate, and is based on Friday’s gas price.

That latest forecast will certainly worry many families, with recent surveys suggesting that nearly half of adults in the UK are struggling to pay their energy bills even ahead of those price rises. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) found that 45 per cent of adults who pay energy bills had found it very or somewhat difficult to do so in the first half of August.

Beyond that, two-thirds of all UK households – an estimated 45 million Britons – will be pushed into fuel poverty by January as they struggle to pay, according to recent reseach from the University of York.

Around 18 million families will find themselves in a financially precarious position due to soaring gas and electricity bills, according to the study, which found that 86.4 per cent of pensioner couples across the UK will fall into fuel poverty – defined as spending more than 10 per cent of their income on energy – by January. Single-parent households with two or more children are the most likely to have financial difficulties as a result of the looming price rises, with some 90.4 per cent set to fall into fuel poverty.

However, Ms Coles expects that the price of some goods may begin to decrease: “Elsewhere there are signs that food inflation could ease in the coming months. Commodity prices have fallen back slightly, which is likely to feed through into prices on the shelves in the next six months.

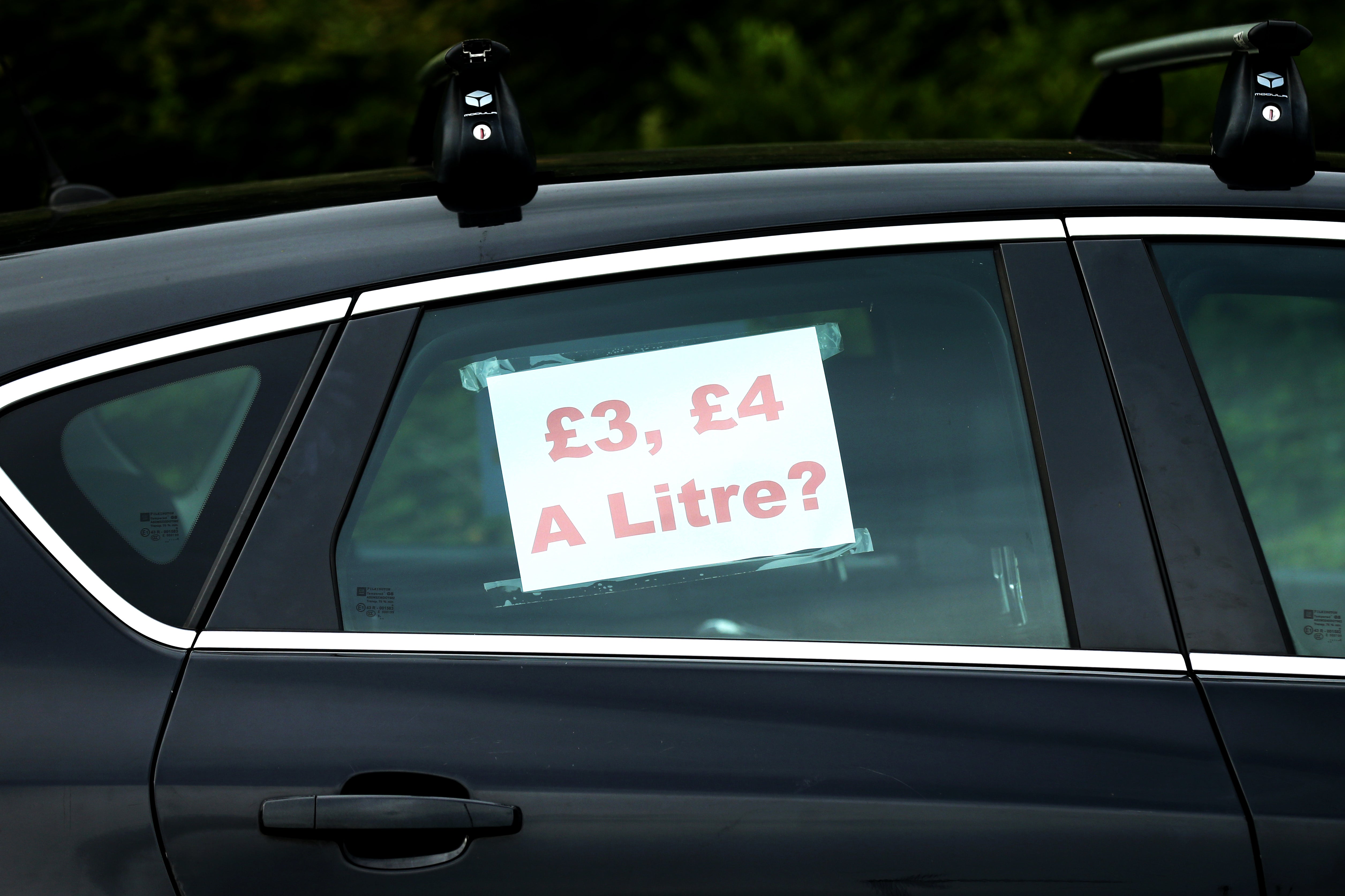

“Meanwhile, the fact that we’re expecting the global economy to slow means petrol prices should continue to come down, too – especially if a deal with Iran is reached to lift sanctions, which could flood the market with fresh supplies.”

Worst fall in wages since the Second World War

Andrew Goodwin, the chief UK economist at Capital Economics, expects wages to continue to fall in real terms up to and including the final three months of next year, with a total decline of 7 per cent. All of this has ramped up the pressure on the government to offer more direct support to those struggling to pay their bills, but Goodwin says its interventions so far have had an effect.

“If you look at the broader measure of real household disposable income, things look a bit better, largely because this factors in the government’s support packages.

“This measure has already been falling continuously since Q1 [the first quarter of] 2021, and we expect it to continue falling up to and including Q1 2023, with the peak-to-trough fall being 5 per cent. That would be the largest two-year fall in real household income since 1944-1945.”

This is already having an effect on consumer behaviour. ONS data shows that UK retail sales picked up in July but continued to show longer-term signs that consumers are cutting back to save money amid soaring inflation. In the three months to July, sales fell by 1.2 per cent, reflecting a gradual decline in spending over the past year.

Speaking about the July figures, Darren Morgan, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said: “They are continuing the downward trend which started last summer. Clothing and household goods sales declined again, with feedback continuing to indicate consumers are cutting back due to increased prices and concerns around affordability and cost of living.” A trend that is likely to continue.

Further large interest-rate hikes on the way

Alex Wright, managing director of Forward FX, predicts further chunky interest-rate hikes from the Bank of England as it attempts to control inflation and end the squeeze on costs.

“Inflation is fast approaching the 11 per cent peak forecast by the Bank of England just a couple of months ago, and there’s no sign of it slowing down. Interest-rate hikes haven’t matched the aggression we’ve seen from the Federal Reserve in the US, where there are signs inflation is coming under control.

“That suggests the Fed’s tougher approach to interest-rate increases is working,” says Wright, who believes the Bank of England will vote for a 0.5, or even a 0.75 percentage point hike when it meets next month.

The Bank has raised its prediction for peak inflation every quarter since May 2021, reaching a high of 13.3 per cent for the fourth quarter of 2022. A number of analysts have expressed surprise that the Bank has not moved quicker to raise interest rates – once inflation gets to a certain point, it will always be costly to bring it back down.

However, Wright adds that raising rates will not solve the supply problems that are the biggest contributor to the recent spike in inflation. It will only act to reduce demand, which accounts for about a quarter of the increase in prices so far.

And he points to other factors that suggest the UK’s problems could drag on for some time.

“The political landscape remains uncertain, with the Tory party leadership contest yet to be resolved, and Brexit continues to weigh heavily on the long-term growth forecasts for the UK.”

UK wage decline ‘much worse than in other countries’

Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, expects real wages to drop by another 4 per cent in the next 12 months, taking the overall decline to 7.4 per cent.

At that point he sees the potential for a recovery if energy prices begin to drop back, which markets currently expect them to as we move towards the second half of next year. Current forecasts suggest that bills will slowly fall, to £5,486 in July and £5,160 in October 2023. Though Goodwin adds a note of caution: “Our commodities team expect energy prices to begin to fall back from next spring, but the situation is hugely uncertain and hinges on developments around the Russian supply to Europe.”

The outlook for wages is “much worse” in the UK than it is in many other countries, but largely because Boris Johnson’s government has focused on giving financial support to households rather than directly controlling energy prices, Tombs says.

“The outlook for real incomes will look pretty similar in the UK and other European countries, especially after the new government is in place and has unveiled its support package,” he says.

Tombs is more optimistic about the situation in the UK than are many other analysts. He adds: “Incorporating our assumptions for extra fiscal support, we expect real disposable incomes... to be only 1.2 per cent lower in Q2 than at present.

“If households continue to draw on savings, then we won’t necessarily slide into a recession.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments