Henry Scott Tuke: Pleasant escapism or iconic images of gay love?

The story of how Henry Scott Tuke’s art has shifted over the last century is a fascinating reflection of our shifting attitudes to homosexuality and the male nude, writes William Cook

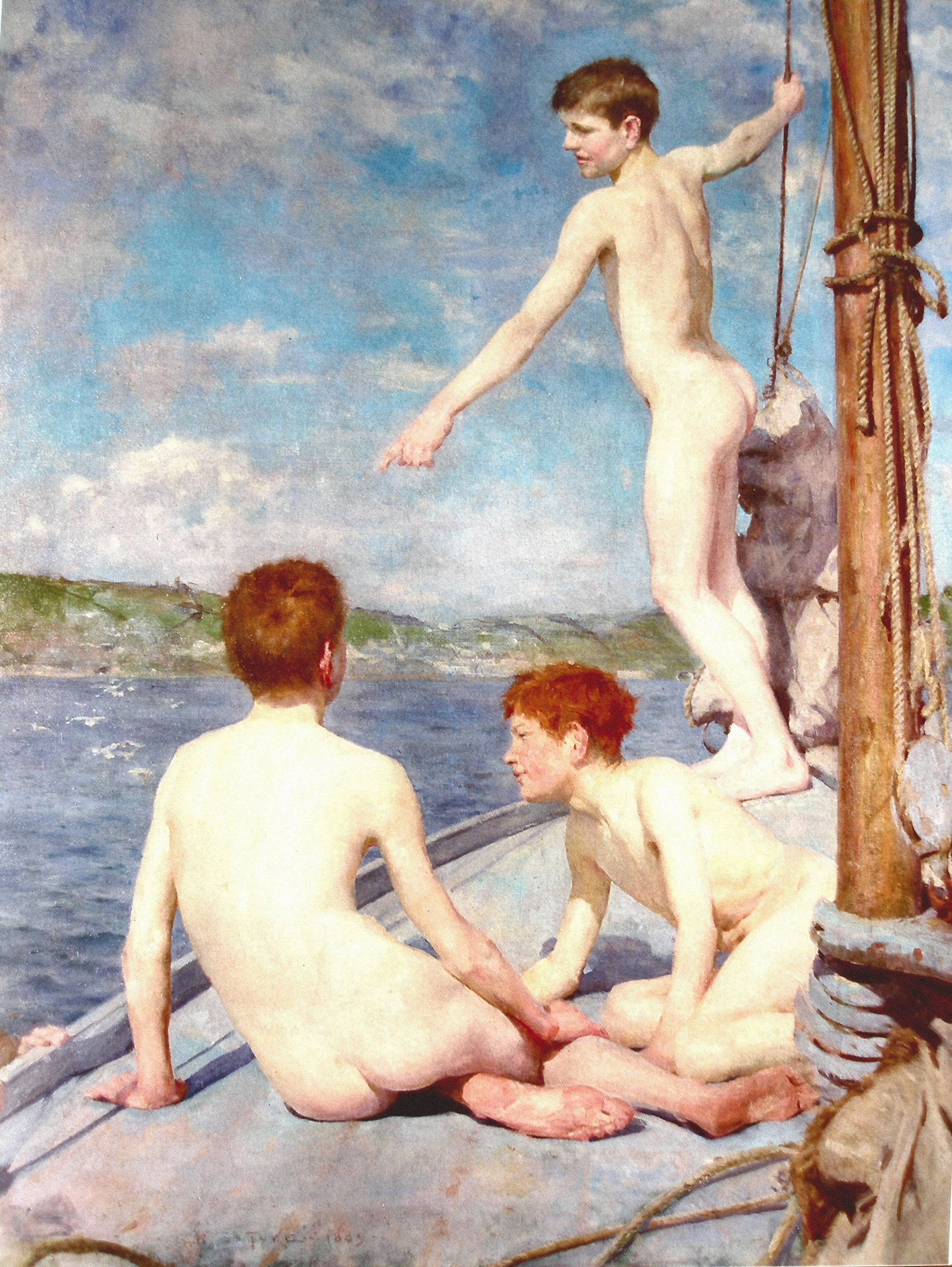

At Watts Gallery, a picturesque museum in leafy Surrey, curator Cicely Robinson is showing me round a room full of male nudes. Young men (some of them very young) are bathing and sunbathing – flexing their lithe, naked bodies, basking in the summer sunshine. Put like that, you might suppose that this exhibition was rather salacious – tasteful erotica at best, possibly something a bit more untoward. Well, you’d be wrong, because this is an exhibition devoted to one of the most admired and respected English artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries – and the story of how our view of these paintings has shifted over the last 100 years is a fascinating reflection of our shifting attitudes to homosexuality and the male nude.

Henry Scott Tuke’s male nudes can be viewed on various different levels. For some viewers, they’re simply pleasant, escapist pastorals. For other viewers, they’re iconic images of gay love. “The variety of interpretations is something we’ve tried to draw out with the exhibition,” says Robinson, who’s chief curator of Watts Gallery. “It’s something that’s still very relevant today.”

Henry Scott Tuke was born in 1858 in York, into a respectable Quaker family. His father, who came from a long line of illustrious psychiatrists, suffered from tuberculosis, so when Henry was a baby the family moved to Falmouth, on the Cornish coast, in the hope that the sea air and warmer weather would do Dad’s chest some good. For father and son, it was a blessing. Henry’s father survived until his late sixties (a decent innings in Victorian England) and Henry enjoyed an idyllic childhood. Growing up beside the seaside, in one of the balmiest parts of Britain, he acquired a passion for sailing and swimming, which fed into his finest works of art.

Henry always wanted to be an artist, and in 1875 he went up to London to study at the Slade School of Fine Art. Then, as now, the Slade was one of Britain’s best art schools, but back then it was the new kid on the block rather than the bastion of the art establishment it’s since become. Founded only a few years before Tuke enrolled, its teaching style was far more modern than other British art schools at that time. While students at other art schools spent weeks on end making meticulous copies of lifeless plaster casts, students at the Slade drew live models, a French tradition which cultivated spontaneity and an intimate understanding of the human body. After five years at the Slade, drawing live nudes had become second nature.

When he left the Slade in 1880, Tuke went to France and Italy, but by 1883 he was back in Cornwall. He spent some time in Newlyn, a fishing port which had attracted numerous artists, and in 1885 he returned to Falmouth, where he spent the rest of his life. The 1880s and 1890s was a good time to be an artist in Cornwall. The new railway had made the county easily accessible from London, yet it still felt like a place apart. An artist could live and work here for a fraction of what it cost in London, the mild climate made painting outdoors a pleasure, and what a wealth of stuff there was to paint! The light was wonderful, the seascapes were spectacular, and fishing communities like Newlyn provided a colourful (and affordable) array of artists’ models. For Tuke and his artistic contemporaries, there was no shortage of local subjects, and no shortage of wealthy buyers for their work.

If Tuke had stayed on in Newlyn, he might have been constricted by the petty politicking of the other artists who’d gathered there, but there were no other artists in Falmouth, and so living in his hometown left him free to develop his own style. He was a local here, not an outsider. His local contacts were unrivalled. He knew every beach and cove. For Tuke, success came early. By the time he’d left the Slade he’d already exhibited at the Royal Academy (he exhibited there virtually every summer, for the next 50 years) and in 1889 he sold a nautical painting (called All Hands to the Pumps!) to the nation for £400 – a small fortune back then, the equivalent of £50,000 today. By the time he’d turned 30, his future as an artist was assured.

So did Victorian and Edwardian art lovers simply regard Tuke’s nudes as pictures of happy summer holidays? On one level, yes indeed

Tuke didn’t only paint naked young men (he was also a successful portraitist) but these are the paintings that stand out. His studies of sailors and fishermen are superb, but his Newlyn contemporaries, like Stanhope Forbes and Walter Langley, did much the same thing just as well. Conversely, his male nudes are unique. There’s nothing else quite like them. So what makes them so special? And how should we regard them today?

Looking at these nudes in 2021, it’s impossible not to regard a good many of them as intensely sexual. No big deal today, of course, now that homosexual imagery has become mainstream, but how would they have been received in the 1890s, at a time when Tuke’s contemporary, Oscar Wilde, was sent to prison for having sex with young men of a similar age? Surprisingly, despite the persecution of homosexuals throughout his lifetime, Tuke didn’t hide his male nudes away. They were exhibited in public galleries and bought by national institutions like the Tate. Even at the time, they were among Tuke’s most popular works. Contemporary critics regarded them as healthy and life-enhancing, “full of bright sunshine, carrying us in an instant from the London fogs and frosts to some sunny stretch of sea”.

So did Victorian and Edwardian art lovers simply regard Tuke’s nudes as pictures of happy summer holidays? On one level, yes indeed. The male nude had been a familiar motif in European art ever since the Renaissance, when artists rediscovered the art of Imperial Rome and Ancient Greece. The male nude was a staple of Ancient Greek and Roman art, and Tuke’s generation revered the culture of that classical epoque like nothing else. Greek and Latin literature were core subjects in the public school curriculum. Public buildings were adorned with neoclassical art. For straight men of Tuke’s generation, nude bathing was a popular pastime. For Victorians and Edwardians, the male nude was a familiar, uncontroversial sight.

Tuke wasn’t the only artist of his generation who painted male nudes, but there’s something about Tuke’s pictures which sets them apart. What’s the difference? That’s hard to say. Tuke never reveals his models’ genitalia, the poses they strike are always tasteful, and there’s nothing lewd about their postures or the expressions on their faces. There’s no way you’d call them pornographic. Yet there’s an erotic charge about them that’s impossible to ignore. This erotic energy was partly due to Tuke’s skill as a painter. Male nudes by his contemporaries seem dry and academic by comparison. Tuke’s studies were full of life, but there was more to it than that. These are paintings by a man who has an emotional sympathy, a deep empathy with other men. In a letter to a friend, Tuke talked about the “aura” of these paintings. His wording was enigmatic, but his meaning was quite clear.

There were plenty of people at the time who recognised this “aura” in Tuke’s work, most notably the Uranians, a network of well-to-do, well-educated homosexual men (such as Oscar Wilde), many of whom revered the classical ideal of love between an older and a younger man. While straight audiences enjoyed Tuke’s nudes on a purely aesthetic level, for Uranians they were an affirmation of “the love that dare not speak its name”.

Was Tuke homosexual too? There’s no way we can know for sure. In all his surviving correspondence there’s no mention of his sexuality, and his sister made no mention of it in the memoir she wrote after he died. However he never married and had no children, so on the whole it seems quite likely. Homosexuality was a criminal offence throughout his lifetime, so if Tuke was homosexual then any reference to it would have been very risky. If he’d revealed his homosexuality, he could have gone to prison. Even after his death, it would have ruined his reputation. Tuke kept a diary throughout his life but only a few volumes survive. There’s some speculation that his sister concealed or destroyed the missing volumes after he died.

If Tuke was a practicing homosexual, then he was extremely discreet – but until homosexuality was (partially) decriminalised in 1967, this was how gay men had to behave in order to survive. Maybe Tuke had sexual relationships with some of his older male models? Maybe he sublimated his sexuality into his paintings? Perhaps that’s what gives them their strange power. With no firm evidence to draw on, it’s all idle speculation – but for me, his life and work is a moving example of how careful gay artists had to be in Tuke’s day to keep their true feelings hidden. “Aware of the dangers of too close an association with the Uranians, Tuke kept a safe distance,” wrote Emmanuel Cooper in his landmark biography, The Life and Work of Henry Scott Tuke. “There is no breath of scandal with regard to his private life.”

Art provided a forum in which gay men could express their sexuality more freely, but even here there were strict limits to what was permissible (think of the coded homosexuality in the works of Oscar Wilde). That discretion, on pain of ostracism, or even prosecution, extended to Tuke’s paintings. He went as far as he could within the legal limits of his day.

Tuke was an English gentleman, and like a lot of English gentlemen he was an enigma. He was both a nonconformist, and a member of the establishment

In our more enlightened age, the homosexual subtext of these paintings is no longer controversial. The only cause for disquiet nowadays is the age of some of Tuke’s models. None of them are prepubescent, but some of them are clearly adolescent. Their precise ages are impossible to discern, but a few of his younger models do make me feel slightly uneasy. And yet I wonder whether this is a sign of the sexual corruption of modern times? We live in a highly sexualised society, in which nudity and sexuality have become more or less synonymous. For Tuke’s contemporaries, a painting of a naked young man could be regarded as a depiction of innocence, a celebration of the joys of youth. Tuke’s pictures are sensual but they’re not overtly sexual. This is a distinction that our desensitised, hypersexualised age has eradicated. Modern society is in some respects more prudish, yet a lot more prurient. “There’s a much closer link now, I think, between nudity and sexuality,” says Robinson. Along the way, something precious has been lost.

Whatever went on in Tuke’s private life, his relationship with his models was a model of propriety. We know this because of the scholarship of Brian Price, who wrote Recollections of Twenty-Four People Who Knew the Artist Henry Scott Tuke. When Price wrote his book, in 1983, Tuke had been dead for half a century, so his surviving models were able to speak quite freely, yet they only spoke about his kindness and probity. Other artists may have exploited or abused their models, male or female, but not Tuke.

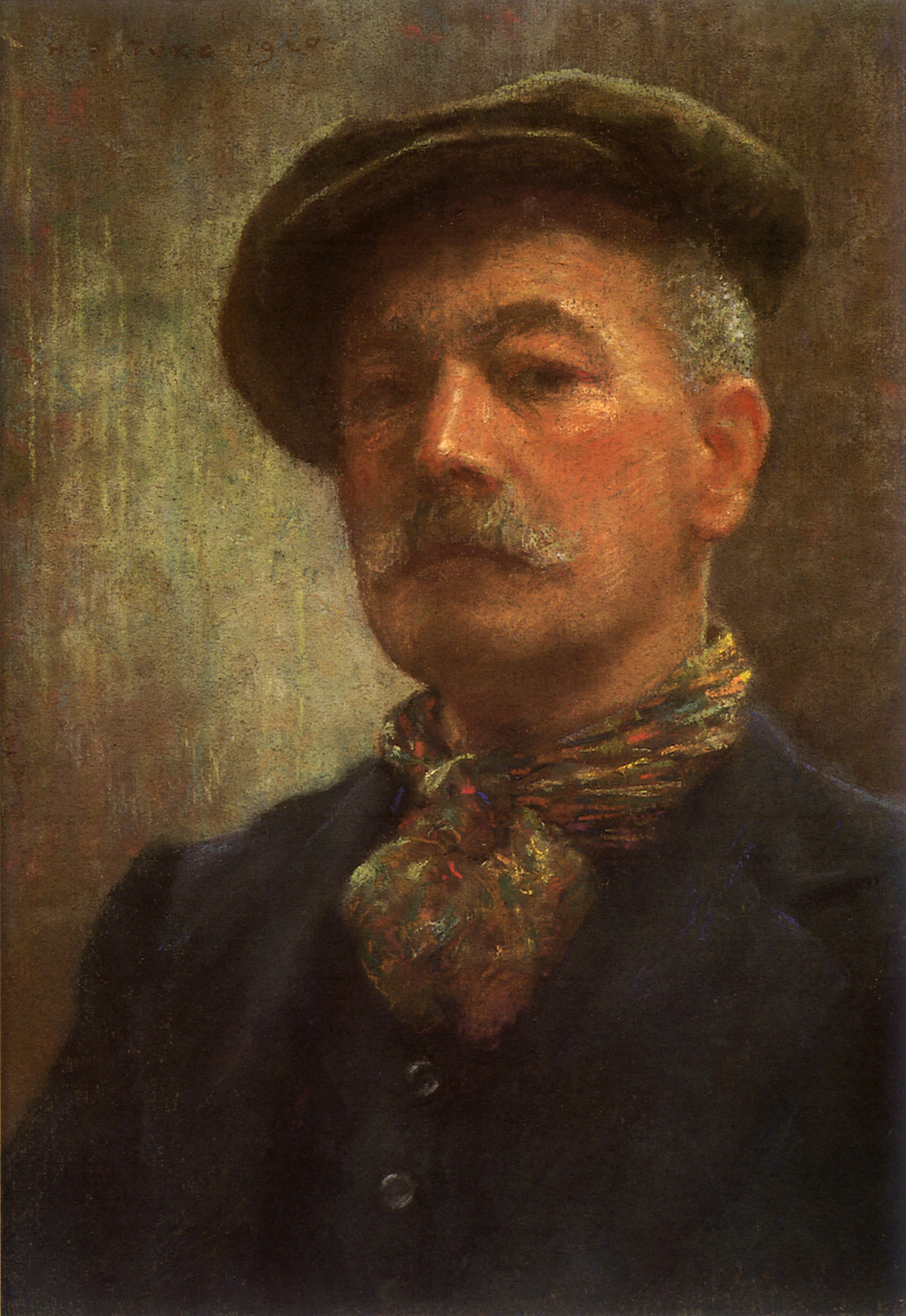

It was scholars like Price and Cooper who revived Tuke’s reputation. After his death in 1929 he’d fallen out of favour, not because of the homosexual content of his paintings, but because of his orthodox painting style. When he started out, in the 1880s, his approach was quite modern, almost impressionistic, but by the 1920s the art world had moved on. Beside the new modernist painters who emerged after the First World War, his conventional figuration seemed old-fashioned. And the First World War killed off something else in his painting too. Several of his models died on the Western Front, and the world he’d painted died with them. Tuke’s paintings represented the self-confidence and easy certainties of Edwardian England, a comfortable nirvana that was swept away forever by the horrors of the trenches.

However as the centenary of Tuke’s death approaches, he’s enjoying a well-earned renaissance. The rise of queer studies has fuelled academic interest in his work, and after several decades in the doldrums figuration is back in fashion. “He has gone through a period of rediscovery as an artist, primarily in queer scholarship,” says Robinson, but his work also enjoys broad appeal way beyond the rarified realm of academia. As Robinson says, he created an image of male beauty that’s still very evocative today. There’s now enough distance between his age and ours for us to see him in his proper context, as a significant and distinctive figure in the story of British art. Homoerotica is a central feature of his work, but it isn’t the only feature. His art conjures up an arcadian image of endless summer – bathing, sunbathing, messing about in boats – which we can all relish and respond to, whether we’re gay or straight or somewhere in-between.

And for me, there’s another aspect to the Tuke revival – namely our growing understanding that sexuality is a spectrum, rather than something binary. Tuke’s paintings show us that male sexual identity is ambiguous. Ostensibly straight men can have homosexual experiences, or homosexual desires they may never act on. A heterosexual man can enjoy the homoeroticism in a Tuke picture, a glimpse of another life he might have led.

Tuke was an English gentleman, and like a lot of English gentlemen he was an enigma. He was both a nonconformist, and a member of the establishment. He loved his country, he loved the outdoor life and he loved other men. His paintings were adored by a huge range of his fellow countrymen, gay and straight. “It interests me more than anything, the play of outdoor light and sunshine on the human form,” he reflected. “I have seen the most beautiful things that eyes can see, and if occasionally one has been able to give even the palest reflection of it, it has been worth the struggle.”

Henry Scott Tuke is at Watts Gallery in Surrey until 12 September 2021, and then at Falmouth Art Gallery in Cornwall from 18 September to 20 November 2021

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments