Wakefield show pays tribute to the enduring genius of Barbara Hepworth

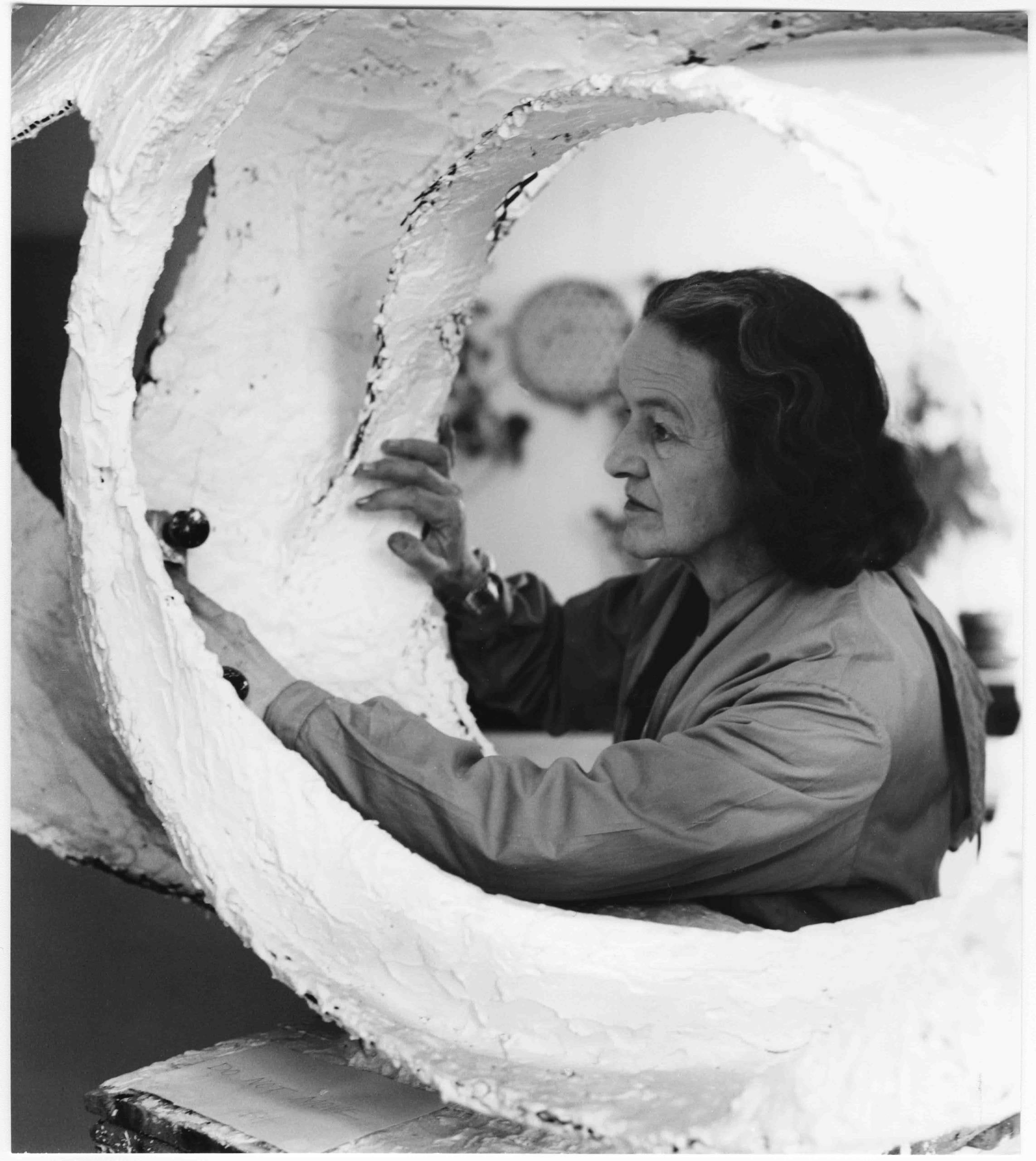

To make it as a female artist in Britain between the wars was tough enough. To make it as a sculptor was even harder. William Cook on one of Britain’s greatest talents

Ten years ago, a new museum opened in Wakefield which transformed the cultural landscape of northern England and cemented the reputation of one of England’s finest artists. That museum was the Hepworth Wakefield, that artist was Barbara Hepworth, and now this stunning gallery is reopening with the most extensive exhibition of her work since she died, in 1975.

“It’s certainly the largest exhibition we’ve ever done,” says Eleanor Clayton, a curator at the gallery, and the author of an absorbing new book about Hepworth, which shares the same name as this landmark show. “We’re able to start from the very beginning, from her roots in Yorkshire, and go all the way through to the last works she made, in the early Seventies.”

Barbara Hepworth – Art & Life sheds fresh light on one of Britain’s greatest sculptors (she hated the word sculptress) and David Chipperfield’s striking building, inspired by her sculptures and built to house them, is the perfect forum for her serene artworks. It’s fitting that this museum is here in her hometown, but to get a proper picture of her work you need to get to know two places: Yorkshire, where she was born and raised, and Cornwall, where she spent the second half of her life. “I’ve been obsessed with Hepworth for many years,” says Clayton. “It was an extraordinary life.”

Barbara Hepworth was born in 1903, into a comfortable, respectable middle-class family. Her father was a civil engineer whose work often took him out into the surrounding countryside, in his new motor car, and he often took her with him. For Barbara these trips were an inspiration – not just the excitement of the ride but above all the wonder of the scenery, which shifted so abruptly from industrial to rural, from grim chimneystacks to barebacked moors. “Every hill and valley became a sculpture in my eyes,” she recalled.

Barbara shone at school. The only subject she disliked was sport. Thankfully, her headmistress allowed her to skip PE and paint instead. She won all sorts of prizes and could have gone to university, but she was determined to become an artist. She went to Leeds School of Art, where she met another aspiring sculptor, a man called Henry Moore. They both went on to the Royal College of Art, in London, where they became firm friends, and maybe more. Professionally as well as personally, Moore held her in high regard. No one was born with more artistic talent, he declared.

It’s remarkable that these two giants of British sculpture were born a few miles apart, a few years apart, and trained as artists side by side. Was this just a coincidence? Well, yes and no. There’s something supremely sculptural about this part of Yorkshire, the stark contrast between rolling hills and dark satanic mills, and this rugged terrain had a profound influenced on both of them.

Yet while their early work had much in common, their interests soon diverged: his sculptures became more monolithic; hers became more ethereal and elemental. As Sally Festing observes, in her insightful biography Barbara Hepworth – A Life of Forms, in some ways Hepworth was the antithesis of Moore. Their mutual fondness and admiration endured, but right from the start she was her own woman. Moore’s robust figures are rooted in reality, Hepworth’s graceful forms speak an abstract language of their own. Like beautiful melodies they have no intrinsic message but they’re somehow full of meaning. “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music,” said the art critic Walter Pater. Hepworth’s sculptures were sonatas in wood and stone.

Throughout Hepworth’s career any artist who deviated from conventional realism met with widespread resistance

After the Royal College of Art, where she flourished, in 1924 Hepworth went to Italy on a travel scholarship. For her, Italy was a revelation – not only the renaissance art, but above all the sunshine. “There had been something lacking in my childhood in Yorkshire and that was light,” she wrote. “The sun never shone enough. The atmosphere rarely cleared, shadows were never sharp, surfaces never brilliant.”

In Italy Hepworth met the young British sculptor John Skeaping, who was also out there on a travel scholarship. They married in Florence in 1925. In 1926 they returned to London and in 1929 their son Paul was born. Hepworth remembered it as a “wonderfully happy time”, but money was tight and juggling art and motherhood was hard.

It wasn’t easy for either of them, but for her it was that much tougher. His work was judged on its own merits, while she was billed in the press as “Mr Skeaping’s young wife” or simply “Mrs JR Skeaping”. Even the rave reviews were patronising. The Yorkshire Evening News called her “a lovely girl with whom nobody would associate a hammer and chisel”.

“I am constantly plagued by this little-woman attitude,” she complained. “There is a deep prejudice against women in art.” Hepworth did a huge amount to dispel this prejudice, but she didn’t do it as a polemicist. It was her tireless dedication which made people realise that women could be sculptors too.

Britain’s innate distaste for modern art was an even bigger obstacle. It’s easy to forget today, now that galleries like Tate Modern have become mainstream tourist attractions, that throughout Hepworth’s career any artist who deviated from conventional realism met with widespread resistance. Even figurative artists like the post-Impressionists were regarded with considerable suspicion, long after they’d become established on the Continent. “The reviewers in the broadsheets were absolutely scathing,” says Clayton. “I think a lot of people thought that it was a kind of joke, that the artists were somehow mocking the viewer – there was an awful lot of, ‘Oh, anyone can do that’.”

In 1932 Hepworth fell in love with the artist Ben Nicholson. She divorced Skeaping in 1933 and in 1934 she gave birth to triplets. This would have been a huge challenge for any artist, especially living in a basement flat with a kitchen that doubled as a bathroom, but somehow Hepworth found a way.

“I have to do all my work between 6:30 at night and three in the morning, as the rest of the day is children and housework,” she revealed. As the triplets got older, she started snatching short spells of work during the day (“I’ve slowly discovered how to create for 30 minutes, cook for 40 minutes, create for another 30 and look after children for 50”). In 1936 Hepworth and Nicholson married (he’d been waiting for his divorce from his first wife to come through) and in 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, the couple relocated to St Ives, in Cornwall. It was here that Hepworth created her greatest works, in a place that became the focus of her later life.

It was Nicholson’s idea to move to Cornwall. He’d already spent some time in St Ives and was keen to return. Hepworth had no connection with the place, but she quickly fell in love with it. Like many other newcomers, before and since, she soon discovered that Cornwall is a place apart, quite separate from the rest of England – and that Penwith, the windswept peninsula at the very end of Cornwall where St Ives is located, is especially wild and remote (even the geology is different, an ancient outcrop of volcanic granite).

“The barbaric and magical countryside of rocky hills, fertile valleys and dynamic coastline of West Penwith has provided me with a background and a soil which compare in strength with those of my childhood,” she enthused.

Yet although London was a long way away, Penwith wasn’t a cultural wilderness. Ever since the 19th century the area had supported a thriving community of artists – incomers like Hepworth, eager to escape the big city, attracted by cheap studio space, spectacular scenery (“unconquerable and strange and, my god, how sculptural”, as she put it) and above all the wonderful light, washed clean by the sea air. Surrounded on three sides by the fierce Atlantic, Penwith feels more like an island than a peninsula. “She was also really inspired by the Neolithic monuments that were there,” says Clayton.

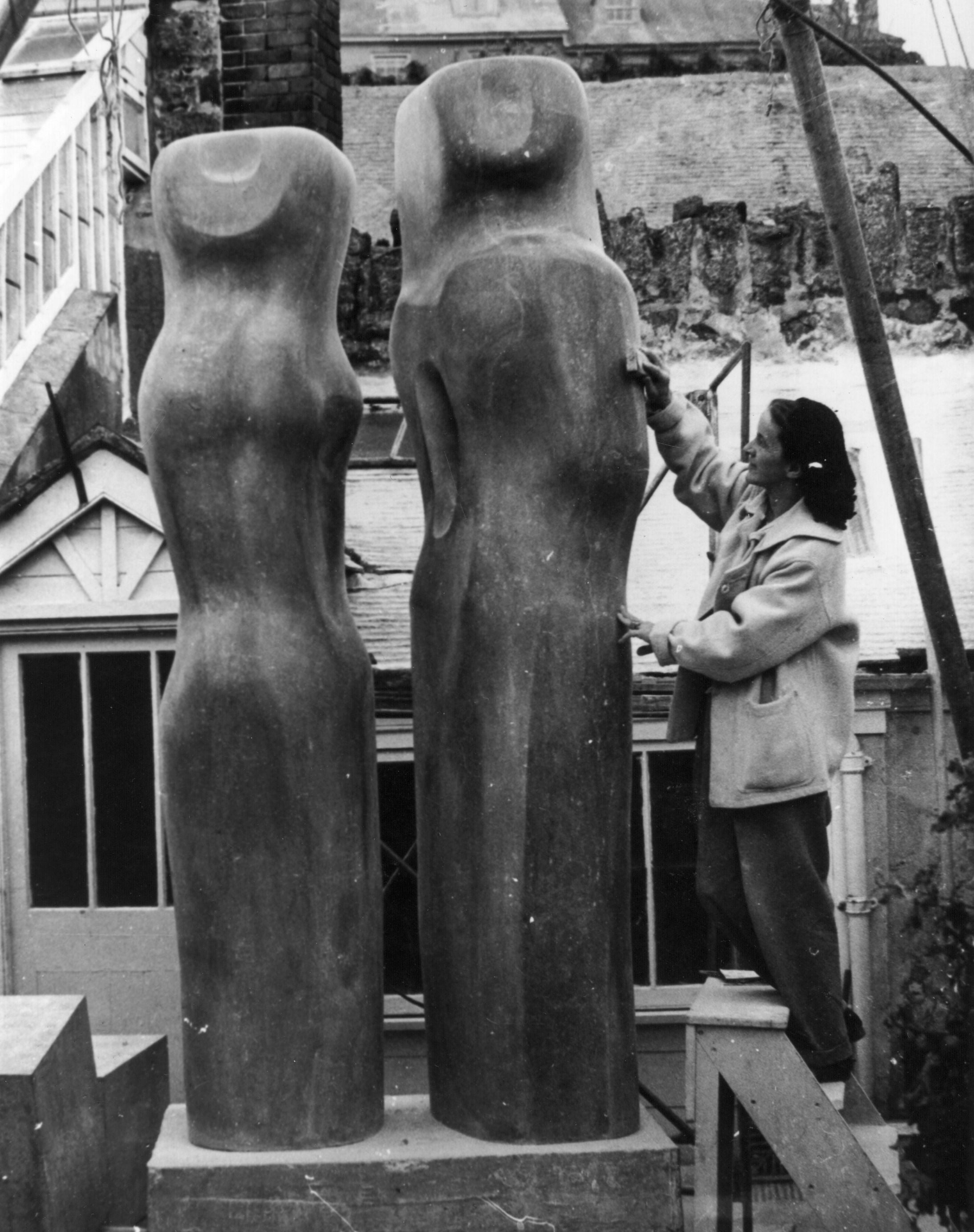

After 20 years as a working mum, Hepworth began to find more time to sculpt and in 1949 she found the perfect studio, a stone cottage called Trewyn in the heart of St Ives. In 1950, she made her home there. In 1951, she and Nicholson divorced. Single for the first time since her early twenties and free from parental duties, her career took off. Her work became larger, more monumental. Her fame spread throughout Europe and America, north and south. Yet even in her fifties, when she’d become an artist of worldwide renown, the institutional sexism of the British press persisted. “It might be possible to mistake the huge-browed Miss Hepworth for a professional intellectual,” reported the Sunday Times in 1955, “but she is in fact the mother of four children”.

“I have never understood why the word feminine is considered to be a compliment to one’s sex if one is a woman,” she retorted, “but has a derogatory meaning when applied to anything else.’

The Sixties represented the peak of her career. Her colossal Single Form for the United Nations headquarters in New York was her most prestigious commission, and a project especially close to her heart (she was a passionate supporter of the UN, and a friend and admirer of its Secretary General, Jorg Hammarskjöld, who commissioned this iconic sculpture, and died in a plane crash before it was completed).

Londoners adore her elegant Winged Figure, which graces John Lewis’s flagship store on Oxford Street. More than any other artist, she overcame Britain’s aversion to modernism. “The last 10 years have been a fulfilment of my youth,” she said, in 1969. Even in her early seventies, she remained at the cutting edge of contemporary culture, in tune with the radical spirit of the times. “She was campaigning for nuclear disarmament, she was campaigning against the Vietnam war,” says Clayton. “She was very much involved in the same sort of ideals as the counter-culture movement.”

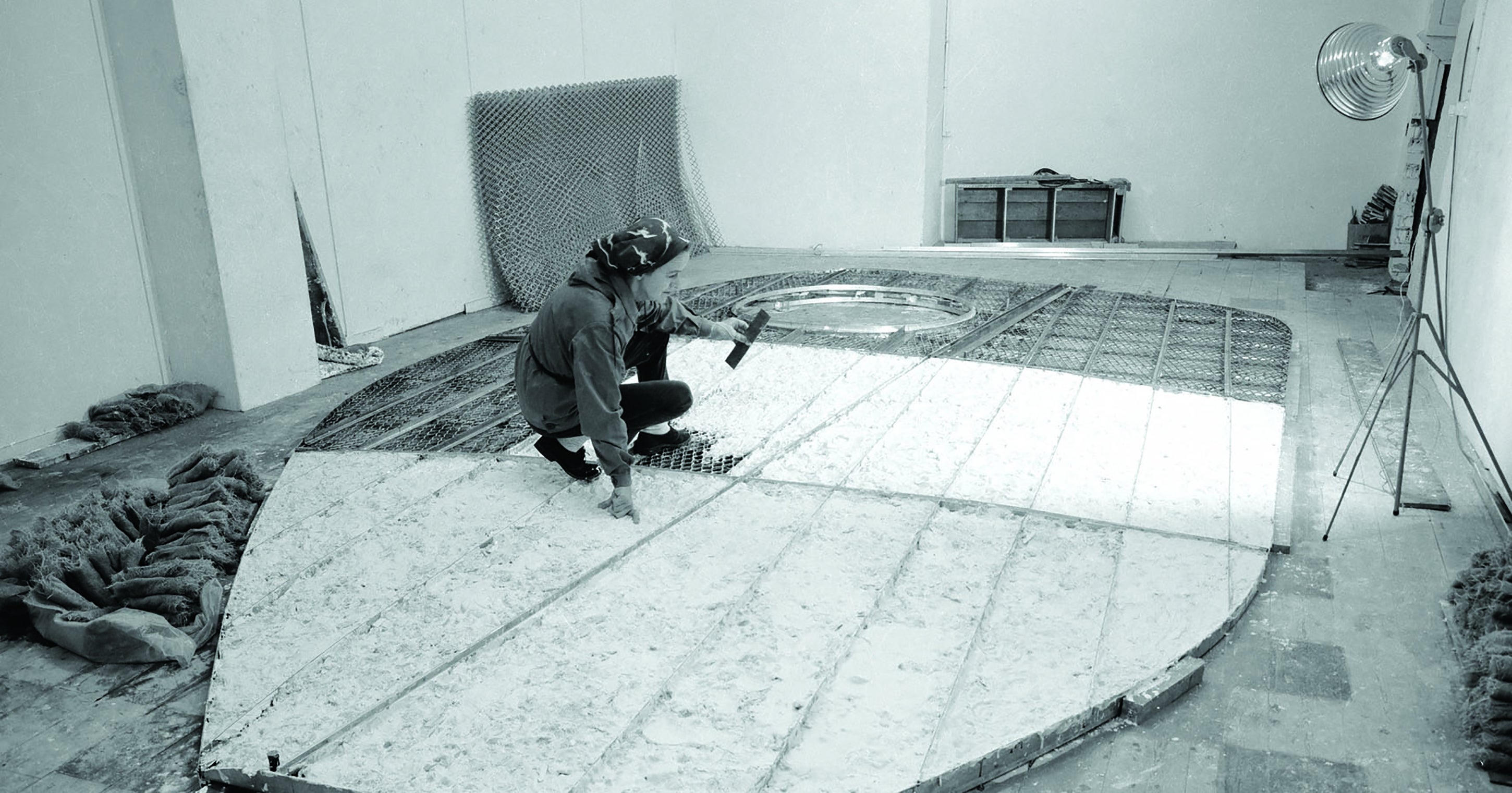

Her final years were dogged by ill health. She carried on smoking, even after treatment for cancer of the tongue, and she drank more than was good for her (were these vices to blame for the nocturnal house fire that killed her, in her beloved Trewyn, in 1975 aged 72?) yet right up until the end, she never eased up. “She was continually inspired to be making new forms that reflected her interest in time and the seasons and the continuing evolution of the world,” says Clayton. “She started experimenting with all sorts of different materials.”

“All the time I am not working I am thinking about sculpture,” she said. “I detest a day of no work, no music, no poetry.”

“She was a strong and difficult woman,” concluded Festing, quite rightly, and that was a big part of her success. To make it as a female artist in Britain between the wars was tough enough. To make it as a female sculptor was even harder. A woman in a man’s world, she had to fight twice as hard for her voice to be heard. “You must have passion, an obsession, to do something,” she said, and what she did will last. Britain is no longer a country that mocks abstraction. Her work was central to that seachange. “Sculpture has its own intrinsic power,” she wrote. “It has natural laws, obeys them and yet rises above them.” Her sculptures obey these natural laws, and ultimately transcend them. And that’s what makes them sing.

In 1976, a year after she died, Trewyn, her home and studio in St Ives, opened as a museum, in accordance with her wishes. It’s thrilling to wander round the place where she lived and worked for 25 years. You feel a lot closer to her sculptures here than you do in a conventional gallery, especially in her sunlit garden, where some of her finest works have pride of place (”She loved going out into her garden and seeing her sculptures by moonlight,” says Clayton).

In 1993, the opening of Tate St Ives, a short walk away, provided a larger stage for her work in the place which became her homeland. Yet for a long time there wasn’t much to see in her native Yorkshire. That all changed in 2011, when the Hepworth Wakefield opened in her hometown. Chipperfield’s serene building is an artwork in its own right, and a large bequest from her family provides an invaluable insight into her work.

Read More:

However, the place where I feel closest to Hepworth is a few miles away, at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, a vast expanse of moorland and parkland, a world away from the grimy mill towns down below. Here you’ll find her Family of Man, an ensemble of timeless statues, like sentinels from an earlier, forgotten age. Seeing these sculptures here, stood together, exposed to the elements, reflecting the changing weather and the changing seasons, I’m reminded of the times her father drove her through this muscular countryside, when she was a little girl, a 100 years ago.

“Perhaps what one wants to say is formed in childhood,” she reflected, “and the rest of life is spent trying to say it.” Standing here, looking out across this vast arena, admiring the contours of the land that formed her, I finally understood exactly what she meant.

Barbara Hepworth – Art & Life is at the Hepworth Gallery, Wakefield (www.hepworthwakefield.org) from 21 May 2021 to 27 February 2022. ‘Barbara Hepworth – Art & Life’ is published by Thames & Hudson (www.thamesandhudson.com), price £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments