‘Men can be challenged, even at the top level’ – the real story of women in chess

In the battle of the sexes, you might think chess would be a level playing field. Sixty-four squares, 16 pieces each, the same rules for men and women... but women still face an uphill struggle, reports William Cook

A miniseries about chess? It sounds like a terrible idea. Two players huddled over a board for hours on end – where’s the fun in that? Yet The Queen’s Gambit was a massive hit, the most popular scripted series on Netflix. And the thing that made it special was that the show’s star was a woman. “It opened up the chess world for many amateurs, for many people who never knew what chess looked like,” says Russian International Master Alina Kashlinskaya. “For women’s chess, it’s a very good step.”

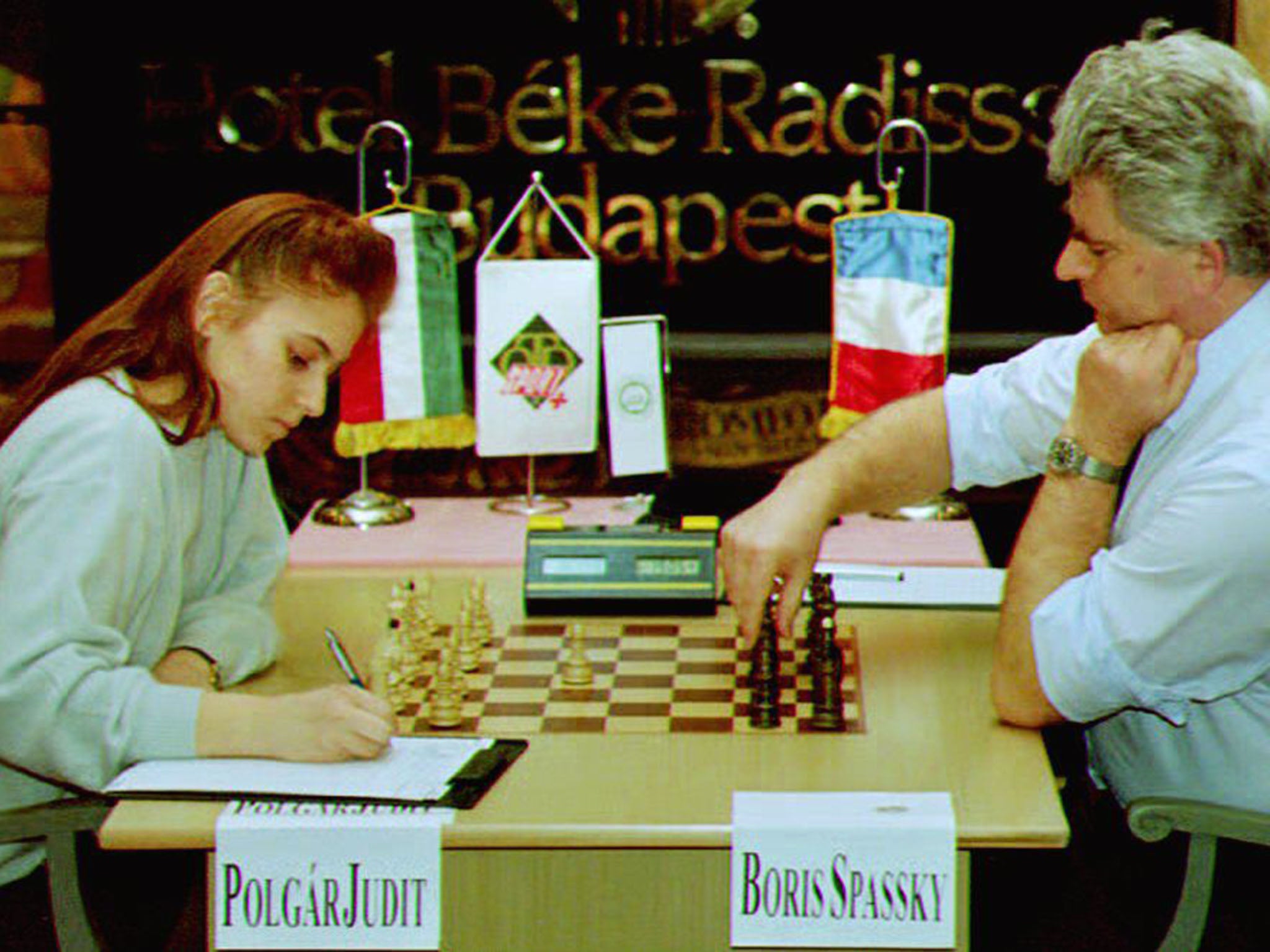

The Queen’s Gambit was widely praised for the accuracy of its chess scenes. Former world champion Garry Kasparov was a consultant on the series – and it showed. Yet there was one thing which didn’t ring true – the way the male players treated the main character, chess prodigy Beth Harmon (portrayed by Anya Taylor-Joy). As Hungarian Grandmaster Judit Polgár told The New York Times: “They were too nice to her.” For, as Polgár found out on the way up, it’s tough to be a woman in a man’s world.

Read More:

In the battle of the sexes, you might think chess would be a level playing field. Sixty-four squares, 16 pieces each – the same rules for men and women. At first glance, there doesn’t seem to be much scope for discrimination. The game is utterly impartial – all the information is on the board. Yet female players face an uphill struggle, as Polgár has observed.

Judit Polgár is the most successful female player in chess history, by some distance. Her two elder sisters were also top players, but she was a class apart. She became the world’s youngest ever grandmaster when she was just 15, and reached number eight in the world rankings (she’s now retired). “She gave hope to the whole women’s chess community – that men can be challenged, even at the top level,” says Alina Kashlinskaya. Yet the prospect of a female world champion is still a long way off.

The numbers speak for themselves. There are currently 1594 grandmasters in the world (the benchmark for a first class player) but only 35 of them are women. Right now, only one of the world’s top 100 players is female, China’s Hou Yifan, ranked 87 – and she’s only the third woman to have ever broken into the top 100. So will a woman ever win the world title? Or are female chess players destined to remain forever second best?

In attempting to explain why female players aren’t (yet) on a par with men, some of the world’s finest (male) players have resorted to crude and clumsy stereotypes. The late great Bobby Fischer took the biscuit. “I guess they’re just not so smart,” he said, bluntly, when asked why women seemed to lag behind. Other players have attempted to be more nuanced but even their more measured comments have sparked controversy. In 2015, Britain’s greatest player, Nigel Short, caused a kerfuffle when he argued that men’s brains were “hardwired” differently, making them intrinsically stronger players. Short’s comments provoked outrage, but he stood by them. He maintained he was simply saying women are better at some things, while men are better at some other things – like chess.

Comparing male and female prowess in any field is bound to be invidious – especially when it comes to chess, which is widely regarded (rightly or wrongly) as the ultimate intelligence test. That’s why Short’s comments were so inflammatory. More than a game but not quite a sport, chess inhabits a strange abstract space midway between art and mathematics. Its infinite permutations constitute a sort of silent music. If boys are innately better at it, that suggests they’re innately better at all sorts of things. To the liberal mind, this is anathema – but don’t the statistics bear this out?

Well, no. In fact, what the statistics indicate is something else entirely. Turns out the main difference between male and female chess players isn’t ability, but opportunity. Teach your son and your daughter how to play and they’ll both pick it up just as easily. Make them follow the same programme and their progress will be much the same. It’s only at the highest level that the disparity becomes clear. Yet this disparity isn’t inborn – it’s actually all about probability. All across the world, at virtually every level, male players outnumber female players by around 10 to one. By chance alone, the best men are far more likely to be stronger than the best women.

Think about it this way: instead of categorising chess players by gender, imagine we decided to categorise them by hair colour. Let’s say 90 per cent of players have brown hair, and only 10 per cent are blonde. Take a sample group of 10 blonde players and 90 brown-haired players, disregarding gender. Give each player a random number, between one and 100. One denotes a beginner and 100 denotes a grandmaster. The other numbers denote all the other levels in between.

The average score of blonde and brown-haired players will probably be much the same, but the grandmaster in the group is far more likely to have brown hair. That’s pretty much the way things pan out when it comes to comparing male and female players. Sure enough, the average abilities of standard male and female players aren’t all that different. It’s only at the elite level that the gender difference becomes clear. Yet this doesn’t indicate that male players are intrinsically better than female players. Given the huge disparity between the number of male and female players, this is exactly the result that a statistician would expect.

So why do far more men play chess than women, from club level all the way up? It’s not a matter of innate attraction, as anyone who’s ever introduced the game to small children will attest. Little girls find chess just as appealing as little boys – the simple beauty of the pieces, the discreet magic of the moves... And yet women aren’t playing at tournament level in anything like the same numbers, as amateurs or professionals. Why not?

The issue of female participation in competitive sport is complex and opaque (and at the top level chess is run like a sport, even if it’s actually something more than that). In patriarchal societies, which actively discourage – or even prohibit – women from competing against men, this discrimination is clear. In more liberal societies, the process is more subtle. So long as chess isn’t regarded as a game for girls, in the schoolyard or the mass media, fewer girls will end up playing. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

All aspiring sports stars have setbacks, moments when they feel like quitting. If you’re the one girl in your chess club, or the only woman in a tournament, those setbacks are bound to feel that much bigger

That’s why The Queen’s Gambit was so important, but even in The Queen’s Gambit Beth Harmon is depicted as being rather odd – and most kids don’t want to look like the odd one out. Persevering with something that’s seen as a bit weird takes a lot of guts (and, usually, a good deal of parental support). All aspiring sports stars have setbacks, moments when they feel like quitting. If you’re the one girl in your chess club, or the only woman in a tournament, those setbacks are bound to feel that much bigger.

And there’s the casual sexism, too. The chess world isn’t especially sexist, but nor is it immune. Leading American chess player and chess writer Jennifer Shahade (author of chess books such as Chess Bitch and Play Like A Girl) created an artwork called Not Particularly Beautiful, which documents 64 sexist comments she’s been subjected to (ie ‘loves to hear herself talk’), displayed on the 64 squares of a giant chessboard.

Shahade’s artwork was inspired by a remarkably similar work of art made way back in 1534 by a Frenchman called Gratien du Pont. Like Shahade’s piece, Du Pont’s artwork is a giant chessboard, adorned with 64 misogynistic comments. Even though Du Pont’s artwork was made 500 years ago, the comments on his board actually aren’t that different to the comments on Shahade’s. Indeed, the most significant difference is that du Pont’s comments are a celebration of misogyny, rather than a critique.

The inspiration for Du Pont’s artwork is revealing. Until the 16th century, chess was slow and ponderous, but then around 1500 a new version of the game appeared, in which the queen could traverse the entire board in a single move (rather than one square at a time, like the king). In this version the queen became the strongest piece, and the king became a weakling. This new version was given the disparaging nickname “madwoman’s chess” (by men, no doubt) but it was this version that prevailed. The concept of a powerful queen protecting a helpless king became the basis of modern chess. For men like Du Pont, this was clearly an uncomfortable transition.

Du Pont’s artwork shows that misogyny in chess is nothing new. Since chess is commonly perceived to be the quintessential cerebral challenge, for a male chauvinist to lose to a woman is an affront to his entire worldview. However even more right-on men can find it surprisingly unsettling. “As in any other field, men don’t like to lose to women, and sometimes they may get angry,” says Ukrainian Grandmaster Anna Muzychuk. Female players have told me shocking tales of men they defeated who refused to shake hands afterwards. One sore loser even scattered his pieces across the board.

Time and time again, in virtually every area of human endeavour, the gap between male and female achievement has been shown to be a matter of nurture, not nature. As societies have become less sexist, women have closed that gap in every field. There’s no reason to suppose that chess will turn out any different. “The gap is getting smaller,” confirms Anna Muzychuk. And she should know. Sure, chess is partly about raw brainpower, but it’s mainly about tactics and strategy, and these are things you have to learn. Like most complex activities, chess is something you get better at the more you do it: practice, practice, practice – morning, noon and night. At almost every level, the best players are usually the ones who’ve played the most. If girls get the same opportunities, they’ll end up being just as good.

However, it isn’t easy to create a competitive environment where all players have an equal chance. Prejudice is a powerful, pernicious force. Unconscious bias is all-pervading. It can take generations to turn things around. So rather than waiting for the world to change, what would happen if you removed a young girl from normal society and created an environment in which she could thrive at chess, free from all the things that hold most women back? Well, now we know – because that’s precisely what happened to the world’s greatest female player, Judit Polgár.

Judit’s father, László Polgár was an educational psychologist who believed that geniuses aren’t born but made. He wrote a thesis about the subject, but he didn’t stop there. Incredibly, he turned his family life into an experiment, in a bid to prove his big idea. With his wife, Klára, he home-schooled his three daughters (far more unusual then than now – especially in Communist Hungary, where he raised his family) and gave them a specialist education, tailor-made to turn them into high-achievers. The outcome was remarkable, particularly when it came to chess.

László didn’t just teach his daughters chess (he also taught them Esperanto, among other things) but it was a key part of their curriculum. The results were spectacular. By the time they’d reached their mid-teens, all three sisters were taking on – and beating – some of the best players in the world. László’s eldest daughter, Susan, became a grandmaster. His second daughter, Sofia, became an International Master. Judit did even better.

“Practically from the moment of my birth, I became involved in an educational experiment,” she told Dominic Lawson, in The Independent. “Even before I came into the world, my parents had already decided I would be a chess player.” And what a player! The only woman to defeat a world number one, she’s beaten 11 current and former world champions.

If the Polgárs had raised three boys this way, this experiment would have been fairly interesting. What made it truly fascinating was that fate gave them three girls. Growing up without any boys around, their daughters weren’t subjected to the usual sexist expectations. They were brought up to believe that chess was something women could do just as well as men – and so they did it. Perhaps this process wouldn’t always yield a player quite as good as Judit (or Susan or Sofia) but, whatever you might think about the morality of this experiment, it looks like persuasive proof that nurture, not nature, is the thing that prevents female players getting to the top.

She was, and is, a ferocious competitor – a psychological attribute that is quite separate from purely intellectual ability

Lawson visited the Polgárs in 1987, when Judit was just 11 years old. Lawson is a decent player, but Judit beat him – blindfold. Apart from her talent, what really struck Lawson that day was Judit’s “killer instinct”, something former US chess champion Joel Benjamin also observed (after a bruising five-hour battle across the board). “She was, and is, a ferocious competitor – a psychological attribute that is quite separate from purely intellectual ability,” noted Lawson. “The ‘killer instinct’ described by Benjamin is something which most parents tend not to welcome in their daughters, but would positively encourage in a son.” Yet Judit’s parents weren’t like most parents, and so a star was born.

Paradoxically, once the Polgár sisters reached chess maturity, in their early teens, fulfilling their full potential meant exposing them to more male contact than normal – not less. Most talented female players mainly end up playing in women-only tournaments. Susan and Sofia Polgár also played against men, with considerable success. By the time Judit came of age, the decision had been made for her. She was far too good for any women-only tournament. No woman in the world could give her a decent game.

Opinion is divided about women-only tournaments. On the upside, they give up-and-coming female players the kind of rewards and recognition they rarely receive in mixed competition. Female winners also help promote the women’s game. As Muzychuk points out: “That motivates more and more girls to play chess.” The prize money in women’s tournaments is still a lot lower than in mixed (ie mainly male) competitions, but it’s gradually increasing, meaning more women can now make a living as professionals.

Consequently, during the past 20 years, the women’s circuit has taken off. But there is a downside, too. Women-only tournaments may make things too easy for the strongest female players. For if the best women only play other women, how will they ever beat the best men? “I believe that for women, it’s more helpful to play in open tournaments,” says Alina Kashlinskaya. “In general, I think it’s better for our development.”

“People can’t understand why there is this separation,” says Muzychuk. “They think chess is just a game where your mental abilities matter, but that’s not true. There is much more behind it, and I think it’s good that women also have their separate events.” It’s a bit like tennis. The best female tennis players are far better than all but the very best men, but at the highest level there’s an element of brute force (rather than skill), which gives men an advantage. Competitive chess is physically gruelling, too. Lawson likened it to doing five hours of degree level exams every day for weeks on end, year after year.

Read More:

But if Judit Polgár can take on the best men, and beat them, surely other women can too? “She has fantastic chess talent, but she is, after all, a woman,” said Kasparov. “No woman can sustain a prolonged battle.” After she beat him, he changed his tune. “If, based on Polgár’s games, to ‘play like a girl’ meant anything in chess, it would mean relentless aggression,” he reflected (she beat Short, too).

After she became a mother, Polgár’s world ranking fell from 10th to 50th. “I wanted to have everything, and it wasn’t really possible,” she said. “In every sport you have to work a lot, you have to focus 100 per cent.”

Maybe one day, men will share the childcare, 50:50. Maybe one day, parenthood will be no more of a career setback for women than it is for men. But I’ve yet to meet a man who said what Polgár said after she was knocked out of an international tournament: “My elimination is great because I can finally get home to my family, to be with my husband and my kids.” Perhaps women are simply a bit too smart to spend their entire lives huddled over a chequered board. For Polgár, in the end there was more to life than chess.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments