Jean-Baptiste ‘Toots’ Thielemans and the enduring appeal of the harmonica

As an exhibition in Thielemans’ hometown of Brussels charts his life and music, Kevin Le Gendre looks at the history of an underappreciated instrument

Every instrument has an image. The piano is largely synonymous with bourgeois respectability and the electric guitar with youthful rebellion. Perhaps more importantly, both of these devices has a pantheon of great players who are too numerous to mention. The harmonica, that small, flat, shiny rectangle that looks like a metal door wedge, lacks the curves and fancy design of a horn, and occupies a far smaller space in public consciousness. Yet it is anything but a footnote in 20th century music. And its history has a real virtuoso, a true icon.

Between the 1950s and millennium the Belgian harmonica player Jean-Baptiste “Toots” Thielemans worked extensively in jazz, pop and film music, recording dozens of tracks that have classic status. Several of the groundbreaking albums by the legendary Quincy Jones, the producer, feature Thielemans purring away quite gloriously, a highpoint of their collaboration being the sumptuous reprise of Marvin Gaye’s soul anthem “What’s Going On”.

A-list pop stars such as Paul Simon, Bobby McFerrin and Billy Joel also availed themselves of the sound of Toots, but it was by way of the small and big screen that he was able to reach the biggest audience imaginable. Consider the following tunes: the breezy, sunny skip of “Sesame Street”, the fraught, shadowy lament of “Theme from Midnight Cowboy” and the poignant strains of Verdi’s heartbreakingly solemn “La Forza Del Destino”, from Jean De Florette. Gracing these soundtracks that marked mainstream global culture between the hippie Sixties and the yuppie Eighties is Thielemans’s harmonica. He played with a delicate, often dreamy finesse, reflecting his origins as an accordion player, but he also had a bold, wily improvisational flair that saw him hold his own among a number of star soloists.

Furthermore, Thielemans had staying power. He was touring until a few years before his death at the age of 94 in 2016, and his impact reached beyond the world of music, crossing to the credible side of celebrity culture. On hearing of his death, Barack Obama took it upon himself to send a letter of condolence to Toots’s widow Huguette.

This year is his centenary, and Toots 100, a superb exhibition on his life and music is currently running at the KBR (Royal National Library) in Brussels, his hometown.

The exhibition gives a real sense of his personality and chronicles his stellar career. He made his breakthrough as a guitarist the Forties, working with swing legend Benny Goodman in Europe, before emigrating to America and joining pianist George Shearing, after which he played anything from easy listening to bossa nova and classical. Thielemans also wrote a great deal. “Bluesette” is his charming signature tune, the first recording of which features him whistling as well as playing guitar.

But it was the harmonica that became his other voice, an alchemy that is crucial in jazz. To mark the opening of the exhibition there was a gala performance in Thielemans’s honour at the splendid Bozar concert hall that featured several of his noted collaborators such as American pianist Kenny Werner, Dutch symphonic ensemble Metropole Orkest, and Brazilian singer Ivan Lins. But the key figure on stage was Gregoire Maret, a 47-year-old Swiss harmonica player cast in the role of Thielemans, and who has, since his debut in the late Nineties established himself as the preeminent exponent of the instrument that is still a relatively rare sight in such esteemed settings.

On a repertoire of the Belgian’s compositions, and other music associated with him, Maret was simply imperious, producing daringly constructed solos underpinned by the strong rhythmic drive and richness of timbre that previously landed him gigs with leading contemporary jazz artists such as Cassandra Wilson, Steve Coleman and Marcus Miller, as well as with stars who also collaborated with Thielemans, notably Pat Metheny and Herbie Hancock. The latter once said after a Maret improvisation that left the audience spellbound at the London jazz festival in 2008. “That little instrument…who would have thought it could do all that?”

Indeed Maret is among the first to recognize that there has been a certain resistance to the credibility of the harmonica. “Yes, ever since I started playing as a teenager I felt the instrument was misjudged, that there was this perception of it being a kind of toy and not very serious,” he comments wryly, before underlining the stature of Thielemans as the man who gave the harmonica its lettres de noblesse, so to speak. “Toots was really the first artist to make it about 100 per cent music and no gimmickry.”

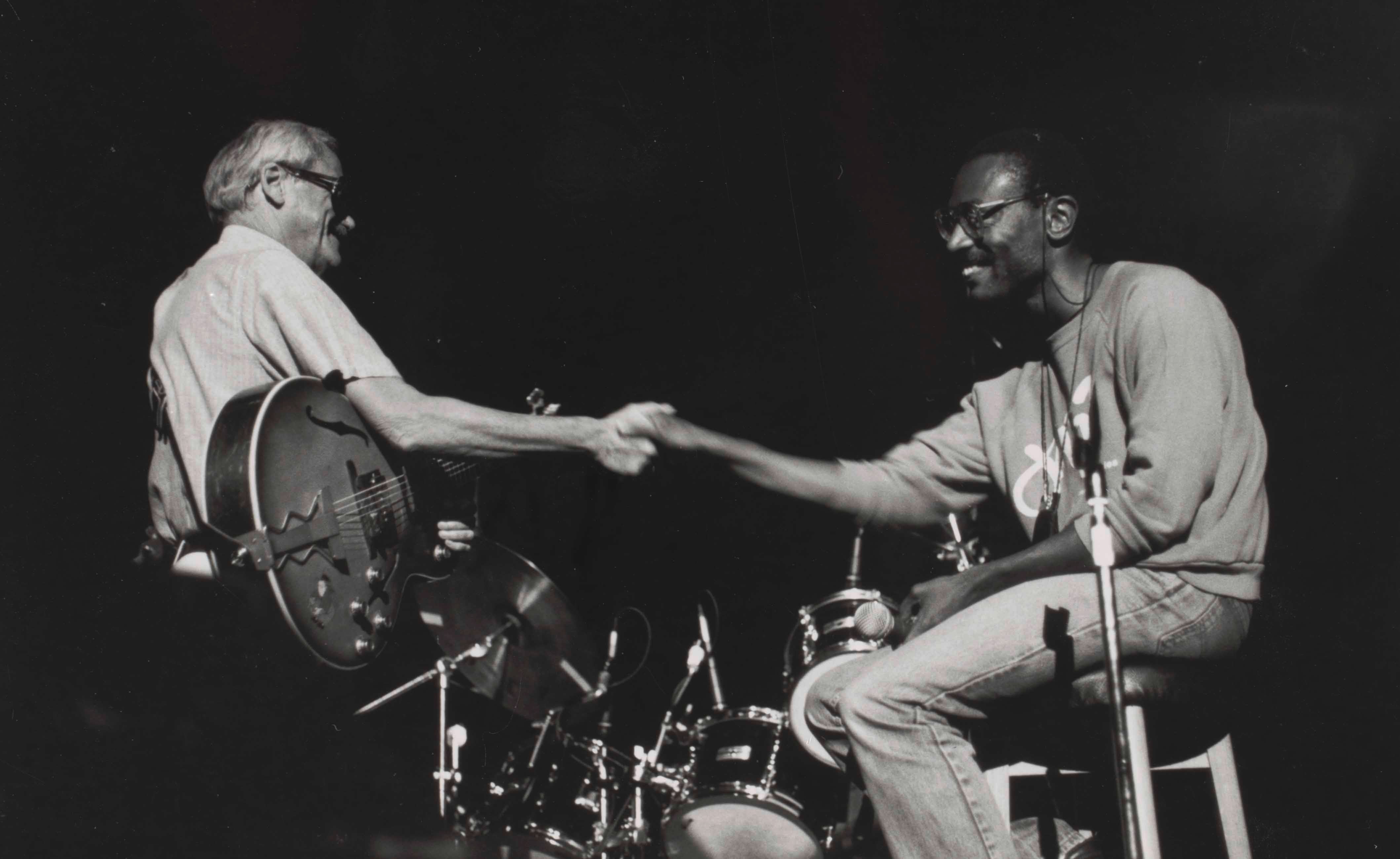

Maret upholds that tenet. And as important as his recordings are there is no substitute for seeing him play live, because of the wealth of spontaneous ideas that fly through the air when he really sets about developing a solo to its full extent. He knew Toots Thielemans very well and was as charmed as anybody by one of the highlights of the Toots 100 exhibition: footage of the Belgian on stage at the prestigious Swedish Polar Music Prize show in 1999. Thielemans is settling into “Bluesette” when none other than Stevie Wonder is led to the stage to join him before he also puts his own harmonica to his lips and starts to blow. Despite the mutual admiration society there is also a kind of “clash of the titans” vibe to the encounter because the pair sound so different, with Wonder having an audibly heavier tone than Thielemans. Perhaps more importantly, you can hear a deep connection between the “little instrument” and Wonder’s church-reared voice, a thing of beauty that has graced some of the most cherished love songs and conscience-raising protest music of the past five decades.

“Stevie plays just like he sings, it’s an extension of himself as a singer,” agrees Maret. “Whatever he feels like singing that’s what he plays on the harmonica. Toots and Stevie are the two major stars on the instrument, and they really have their own identities. But Stevie had actually been a fan of Toots from his early years. They don’t play at the same volume at all. Stevie is much louder and Toots is more delicate, also because he had asthma as a child so he had to adapt his technique to suit his body. And it worked out perfectly for him. Stevie’s not overly technical but he is very lyrical. He plays in a different way because he comes from a background of singing.”

Toots played with a delicate, often dreamy, finesse, reflecting his origins as an accordion player, but he also had a bold, wily improvisational flair

Though a skilled multi-instrumentalist Wonder’s embrace of the harmonica is hugely symbolic because it lays bare the place of the instrument at the heart of African-American musical history. It is often referred to as the “blues harp”, precisely because of the substantial role it has played in the blues and its most noted offshoot, R&B. Reach back to the 1920s and investigate the music of the legendary Clara Smith (who along with Mamie and Bessie was one of the revered trinity of Smiths) and you’ll hear harmonica player Herbert Leonard enhance classics such as “My Doggone Lazy Man” with a simple, slippy see-saw of a countermelody, though he struggles to be heard over the singer’s rugged delivery and chugging chords of a guitar.

The six-string was seen as a much more manly “axe” at the time, and it took centre stage in the subsequent decades, yet by the mid-1930s the likes of Sonny Boy Williamson I had broadened the vocabulary of the harmonica and paved the way for, in the Forties and Fifties brash new talents as Junior Wells, Sonny Terry, Snooky Prior and Little Walter. Walter’s extraordinary 1955 hit “My Babe”, derived from the gospel song “This Train”, put the blues harp way out front as, between the sung verses, he wailed away for a mammoth 24 bars, producing a series of rolling, tumbling, sliding phrases and flickering crescendos to hold the interest with as much authority as any guitar hero. Moreover, Walter made an exponential leap forward by clamping his harmonica to a microphone so that he could be heard over a fully amplified band, and he also confected wonderfully grimy distortion and juddering effects to drag the instrument into the 20th century, when both the times and technology were changing.

Less fashionable than the guitar among teens who wanted a shot at the big time in the wake of the beat music vogue the harmonica nonetheless popped up on key moments in Sixties pop: Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind”, The Beatles’ “Love Me Do”, The Yardbirds’ “Train Kept A Rollin’” and Millie Small’s “My Boy Lollipop”. Between them these songs sketched out the futures of folk-rock, hard rock, and ska, and it is entirely symbolic that the blues harp stands as a common denominator between them, as if it represents a heritage that is too rich to discard, regardless of whether the new exponent is playing with a heavy backbeat or fluid swing. Then again Stevie Wonder’s “Fingertips”, made in the same decade, was a sizzling piece of dance music that cast the harmonica over a wrangling Cuban rhythm and busy, blustery horns.

In an entirely different register is the music of Larry Adler. The much-admired American star played harmonica concertos written for him by renowned composers Cyril Scott, Jean Berger and Malcolm Arnold, and also performed arrangements of Bartok, Stravinsky, Ravel and Mozart. Like Thielemans he had the common touch and worked with major league pop stars such as Sting, Kate Bush and Carly Simon.

Straddling many worlds, bridging the gap between radio tunes and symphony hall fare, the harmonica is one of the most versatile and in many ways beguiling of instruments, The sound palette is astoundingly rich, with a dynamic range that runs from sweet tenderness to stark aggression. Slide the vents across one’s lips and it hisses into life, but blow hard and it squawks like a farmyard rooster. Not for nothing did the pioneering blues men such as Sonny Terry realize that the harmonica could be a potent evocative force of what they heard in nature and thus made it growl alongside their own vocal whoops. Right on cue, the Sixties country rock band Area Code 615 made a rollicking tune in the same vein, “Stone Fox Chase”, that reached millions of viewers when it was chosen as the theme for Seventies music show The Old Grey Whistle Test. The opening bars of the song presented the harmonica as a stridently explosive complement to a syncopated drumbeat, and together the two instruments were skillfully deployed to build a bridge between tradition and modernity.

You also hear that in the group War, one of the definitive funk outfits of the same decade. Its Danish harmonica player Lee Oskar gave them an edginess that perfectly suited Afro-Latin-tinged riffs and futuristic synthesizers, as can be heard on the mesmerizing club favourite “Galaxy”, which is groove science of the highest order.

What adds another layer of complexity to the history of the instrument is its decisive evolution. One of the many attention-grabbing displays at Toots 100 presents the different makes and models, above all the diatonic harmonica, favoured by many blues players, which was tuned in one major key over three octaves, and the chromatic, which offered all 12 keys, and thus far more tonal options. Then there are novelties like the “Trumpet harmonica”, which has what looks like miniature ice cream cones stuck on the small rectangular body, as well as instruments that are part of the bigger gene pool, such as the accordion, the bandoneon, the melodica, which found favour with Jamaican musicians like the legendary Augustus Pablo, the Indian harmonium and the Chinese sheng. Instrument makers in different parts of the world were all drawn to the idea of a device that could be as haunting as it is uplifting, which is maybe why the harmonica, in its bittersweet way, resonated with Thielemans. As he put it: “I feel best in that space between a tear and a smile.”

The fact that one of the other names for the harmonica is “mouth organ” is intriguing because it refers to a keyboard, with all its implications of harmonic richness, and the human voice, with its timeless history of emotion and artistry. And it is perhaps the first part of the compound that is most interesting because the harmonica is actually a reed instrument that requires lung capacity and breath control, just as a horn does, and the range of techniques that are applied to both devices goes a long way to explaining why a harmonica virtuoso produces such depth of feeling. When a master player starts to use vibrato and provocatively bend notes, sometimes giving them that cry-baby resonance that is not a million miles from the rhythmic wailing of an electric guitarist who works a wah-wah pedal, the effect is exhilarating. The blues harp rocks out.

It can be very close to the sound of singing, making it suitable for both joy and despair, as heard in both European folk and American roots music, particularly for cowboys who get real lonesome when night falls. Then again, is there anything more chillingly eerie than the theme Ennio Morricone wrote for Once Upon a Time In The West, Sergio Leone’s classic of grizzled gunslinger cinema? “Man With A Harmonica” is a concise requiem for cold-eyed killers who, before putting finger on trigger, hold the little instrument to their lips. They sound like whispering death.

So powerful was that ghostly exhalation that it was reborn in the 1990s, as a sample on “Dub Be Good To Me”, Beats International’s cover of the hit by Eighties soul combo SOS band, thus providing a neat summary of how the pocket-sized harmonica travels through time and across musical territory, leaving the big screen for the dancefloor, moving from classical composition to hip-hop production. And with the likes of young British soloist Philip Achille as its latest champion the harmonica still has much to say in any contemporary setting. Gregoire Maret is looking to the future: “I have seen a lot of new players who realise the harmonica is something special.”

Toots 100 is at KBR, Brussels, until 31 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments