Le Mans at 100: the story of the world’s greatest motor race

As the gruelling 24-hour race reaches its centenary, Mick O'Hare looks at how it grew from humble beginnings into an annual highlight for fans around the globe

Rain and wind, hail and mud. And the bits of the track that weren’t turned into a bog resembled a skating rink. It seemed like pre-race predictions that no car would finish the course might come true. But of 33 starters, a full 30 made it to the chequered flag.

The weekend of 10-11 June marks the 100th anniversary of the world’s most gruelling motor race. By the time the winning car crosses the line it will have covered more than 5,000km. Back at that sodden first race in 1923 the leading car completed fewer than 2,300, but it had set in motion the most punishing, most venerable and perhaps most revered motor race on the planet – Les Vingt-Quatres Heures du Mans – the Le Mans 24-Hour Race.

The great constructors who enter Le Mans – Toyota, Ferrari, Cadillac and Porsche among them – have one intent: to sell cars. Despite the fame and fortune that will be accorded to the winning team of three drivers come Sunday, for the manufacturers’ success or otherwise will not be judged by what happens on the track, but by how much sales of their vehicles increase over the next 12 months.

That imperative, of course, matters little to the thousands who flock to the Sarthe region of France every June to witness the greatest of all endurance races, nor to the millions watching on TV. For them the sport is paramount. But to the manufacturers spending millions of euros, this is their shop window.

The romance surrounding the Le Mans 24-Hour Race is perhaps matched only by the glamour of the Monaco Grand Prix and the financial rewards on offer to the winner of America’s Indianapolis 500. Multitudinous are the claims to be the world’s greatest motor race. But nowhere, despite all the high-tech machinery on show, does any race butt up as hard against legend as it does at Le Mans. For many fans, it’s the only one that matters.

These days the race traditionally starts at 4pm on the Saturday nearest the summer solstice and finishes at 4pm the following day. It’s called endurance racing for a reason. Cars of varying speeds and drivers of varying ability race through the night, reaching top speeds on the Mulsanne Straight of 300km per hour, their headlights picking out slower cars ahead which are encountered at frightening regularity. Choose the wrong side to pass and calamity ensues. Today, safety is paramount but over the past century Le Mans has claimed more than 100 lives, including those of 83 spectators when in 1955 Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes took flight and ploughed into the crowd. It was the most devastating accident in motorsport history.

And, if conditions like those of 1923 are repeated, drivers also have to contend with blinding spray. “When it rains I wish I was anywhere else on Earth,” says five-time winner Frank Biela. Wet or dry, every 45 minutes or so cars stop to refuel and, less often, change tyres and drivers. With 25,000 gear changes and four-fifths of the race run at full throttle, cars continually need servicing. As dawn approaches, only halfway through the race, drivers are already fatigued, taking it in turns to grab sleep as they share stints with teammates.

These days teams have a rotating roster of three drivers but until 1953 when the rules changed, some would attempt to drive the entire 24 hours alone. Only one succeeded, Yorkshireman Edward Ramsden Hall. In 1950 he somehow dragged his ageing Bentley into eighth place. When asked by journalist Denis Jenkinson “How?” Hall replied: “Green overalls dear boy, green overalls.” The last driver to attempt to go solo was Levegh, three years before his terrible accident. And he so nearly won. Leading with only 50 minutes remaining, fatigue caused him to miss a gear change and break his Talbot’s crankshaft. It would, perhaps, have been the greatest of all Le Mans triumphs.

Of course, all legends have a beginning. And the legend that is Le Mans began when the Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) set out to discover which car was the most durable. Rivals in the flourishing inter-war automobile industry had long been making exaggerated claims about their vehicles. The ACO wanted proof. The competition was the brainchild of three men: motoring journalist Charles Faroux, Georges Durand, secretary of the ACO and Emile Coquille who donated the Rudge-Whitworth Trophy.

No victor would be declared. The “race” was simply a test of endurance and reliability. The Rudge-Whitworth Trophy would be triennial, only awarded to cars that competed in three consecutive events thus demonstrating longevity and durability. Later this convoluted process was replaced by something equally arcane: an “Index of Performance” not race position, would determine the outcome.

But once the public and the press caught wind of the event, it turned out they cared not one jot for the loftier aims of the ACO. They were interested only in who crossed the line first. A century later very few people care about the Index of Performance.

Le Mans does this, some drivers love it, others hate it. But victory there is a triumph unrivalled elsewhere

But the 33 starters on 26 May 1923 did. They represented 18 manufacturers, all but three of them French and all hoping their car would prove the most sturdy. The unpaved course was 17.4km long (it’s 13.6 today), stony and sandy. The 6km Mulsanne Straight was, however, part of that original track. In its heyday speeds along it topped 400km per hour although today it is punctuated by chicanes added to keep drivers alert in the small hours. Previously the Mulsanne had a reputation of sending drivers to sleep in the small hours, the couple of minutes’ respite it offered from gear-changing and braking causing them to nod off.

Then, as now, most of the circuit is, for 51 weeks of the year, public road – to everyday motorists the Mulsanne is known as the RD338 to Tours – with little to show what happens every June save for a painted kerb or crash barrier, of which there were none in 1923. Tar wasn’t applied to the track until 1925, so drivers were spattered with stones kicked up by cars ahead. The pits were hastily erected tents, open to the elements. And then it rained. As members of the ACO dined under cover on 50 chickens and 450 bottles of champagne and were entertained by an orchestra in the cocktail bar they had insisted on, drivers taking the start in their open-topped sports touring cars were contending with wind and hail.

The rules were complex. Two drivers were nominated for each car, although there was no stipulation that both had to race. Cars, divided into classes depending on design and speed – as they are today – had to have at least two seats. Those with a larger engine capacity required four. All had to carry 60 kilos of ballast to represent a passenger and if they broke down on track only the driver and a toolkit, carried in the car, could fix the problem (this latter rule still applies today).

Another rule which also applies today is that cars had to be fully road legal – headlights mirrors, indicators – and a certain number had to be produced to avoid one-off prototypes being built purely for the purpose of winning the race, as happens in Formula 1. Teams required fire insurance – refuelling was somewhat haphazard – and lastly the ACO invoked its still extant clause that cars and teams must conform to “the spirit of the race”. Gamesmanship, even if strictly within the rules, can lead to exclusion with no right of appeal.

Despite the technical and meteorological hurdles the field departed in a haze of spray. Early laps saw the narrow tyres of the era churn the track into a rutted quagmire. Most drivers discarded their goggles because sludge splattered the glass. It was easier to blink away the spray.

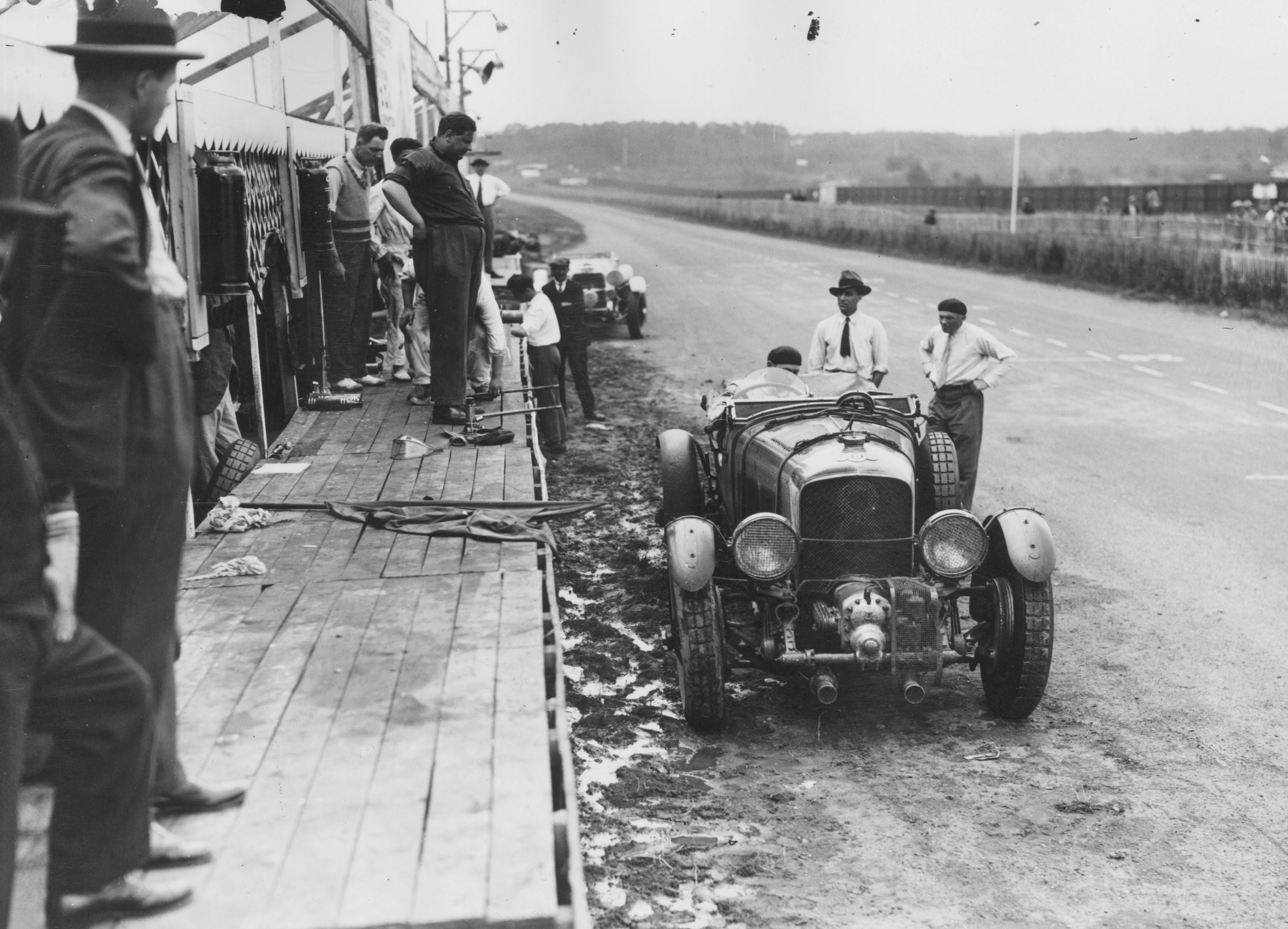

Stories of stoicism and derring-do abounded. The sole British entry, a privately entered Bentley driven by John Duff and Frank Clement, had one headlight shattered by a stone with another puncturing its fuel tank. Clement had to park up, jog to the pits to pick up fuel and a cork to plug the hole and then borrow a cycle from a gendarme to head back. It took him two hours. The Bentley still came home fifth. Later the same would happen to René Marie’s Bugatti.

The rain was so heavy it penetrated the primitive waterproofing of the cars’ headlights. One by one they failed, leading to convoys of cars tentatively picking their way through the darkness line-astern behind those with functioning lights. The Chenard team drivers were given hand-held acetylene spotlamps to aid their progress. Nonetheless, the Excelsior of Gonzaque Lécureul slid off in the darkness. It took him an hour to dig his car out of a ditch. The weather was so bad and temperatures so low that the maker of Hartford’s shock absorbers set up what they called a respite hotel, offering drivers finishing their stints onion soup and red wine.

The delay to the Bentley meant the battle for “victory” came down to a Chenard et Walcker driven by André Lagache and René Leonard, Raoul Bachmann and Christian Dauvergne in their identical car and two Bignans driven by Raymond de Tornaco and Paul Gros, and Philippe de Marne and Jean Martin. In the end, the conditions meant success came the way of the car that best rose to the challenge, exactly as the organisers hoped. Lagache and Leonard were first over the line having covered 128 laps at an average speed of 92km per hour. The winners of the 2022 race, Sebastien Buemi, Brendon Hartley and Ryo Hirakawa in a Toyota, covered 380 laps at 219km per hour.

Of course, in 1923, there was officially no winner although modern records tend to regard Lagache and Leonard as the inaugural victors. By 1928 the ACO had realised that the public had no interest in the Index of Performance and began awarding an “Annual Distance Cup”, to the car that travelled the furthest over the 24 hours. Or, in today’s terms, the winner.

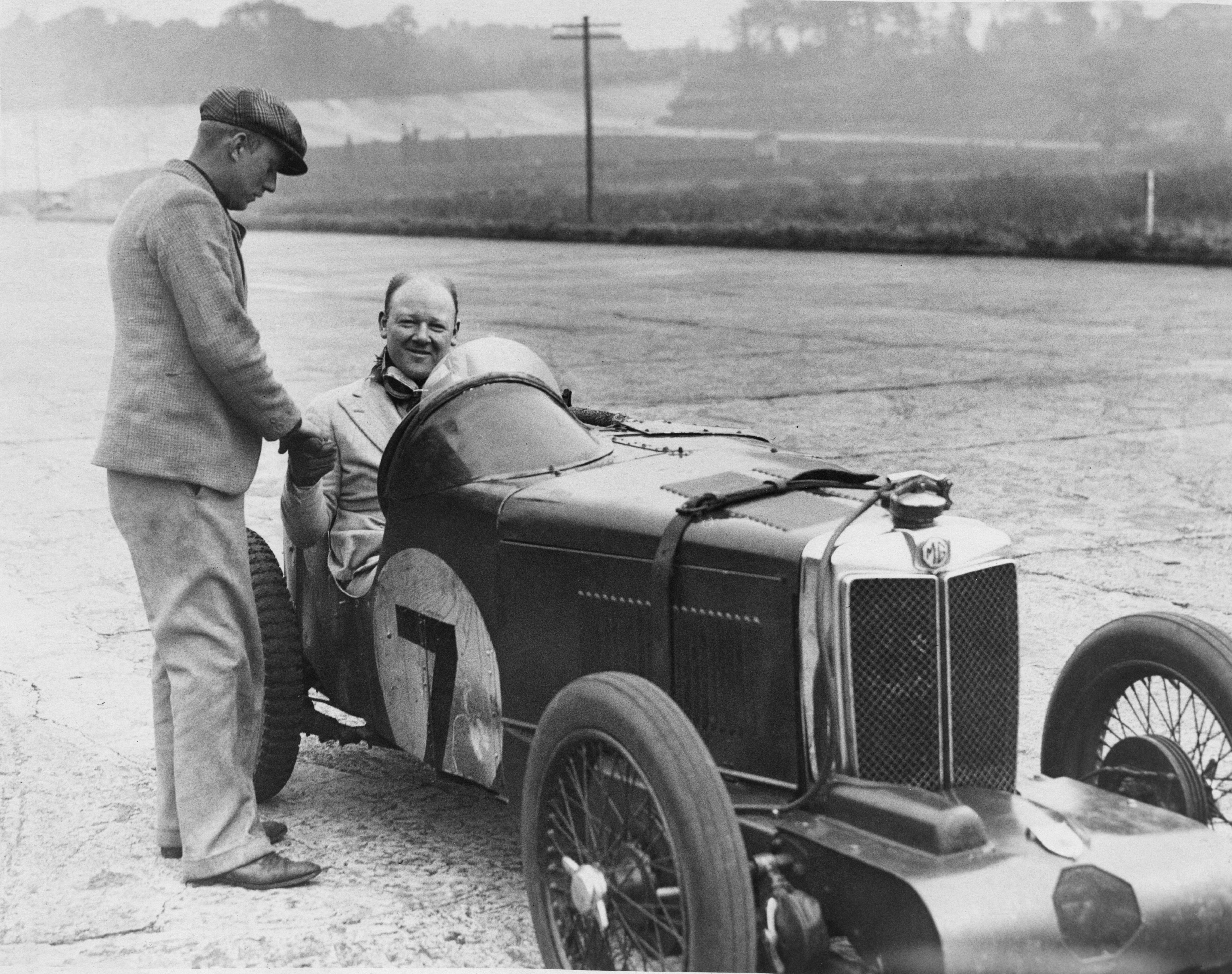

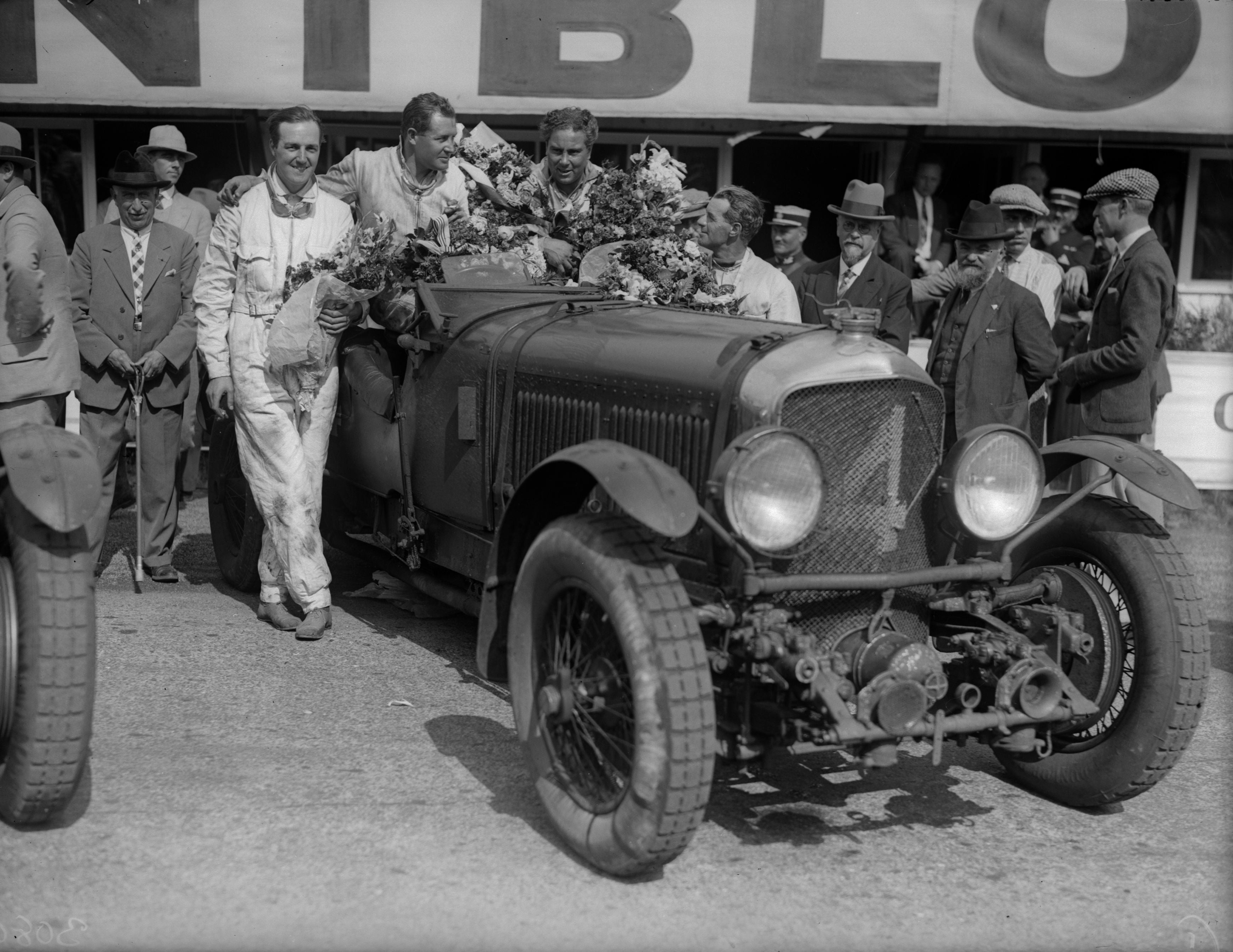

More great races would follow. The first British winner was Bentley whose founder WO Bentley had been at that first race and was determined a British car should subsequently prevail. It did, his cars driven by the eponymous Bentley Boys – a group of wealthy, privately educated Britons, some of who would change into dinner jackets to continue racing once evening arrived – won four straight races between 1927 and 1930. This began a British love affair with the race that continues to this day.

British success continued into the 1950s with Jaguar emulating Bentley’s dominance, and returning to win twice more in 1988 and 1990. Between those triumphs came the golden era of the 1960s and early 1970s as thunderous Ferraris, Fords and Porsches with engine capacities of up to 7l tussled for supremacy. This era produced probably the finest race of all time when for the final three hours of the 1969 event Belgian Jacky Ickx in a Ford GT40 and German Hans Herrmann in a Porsche 908 battled nose-to-tail, door-handle-to-door-handle with Ickx prevailing in the closest ever non-staged Le Mans finish. Ickx, who won the race six times and is often described as “Mr Le Mans”, says: “In hindsight it was my greatest race although at the time I remember just feeling relieved. Le Mans does this, some drivers love it, others hate it. But victory there is a triumph unrivalled elsewhere.”

And, unlike Formula One, women have had success at Le Mans, despite being banned from the race between 1957 and 1971 because it was deemed “too dangerous”. Odette Siko first raced at Le Mans in 1930, sharing a class-winning Alfa-Romeo with male driver Louis Charavel in 1932. There have since been two class wins by all-female teams in 1974 and 1975.

There’s the atmosphere, the subtleties, the ritual and above all the uncertainty of outcome. It’s a race everybody wants to win but few do

In more recent times the great Japanese marque Toyota has dominated, winning the last five editions of the race. However, it is equally remembered for a race it didn’t win. In 2016, with victory almost assured, the leading Toyota being driven by Kazuki Nakajima expired on the final lap handing victory to the Porsche of Marc Lieb, Romain Dumas and Neel Jani in the most dramatic of circumstances.

Yet perhaps even that astonishing race is eclipsed by the fairytale of 1953. In practice the day before the race Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton’s Jaguar was disqualified for an administrative infringement. Distraught, they headed into town to drown their sorrows. But their team manager Lofty England explained to the ACO that it had all been an honest mistake and they were reinstated. England headed out to look for his drivers and discovered them rather worse for wear, slumped in the street outside a bar. They tossed a coin to decide who had the least worst hangover, knocked back another brandy (it wouldn’t be allowed today), and started the race. Twenty-four hours later they’d won it.

“It’s stories such as these which provide the mystique,” wrote the late Brian Laban, author and Le Mans historian. “And there’s the atmosphere, the subtleties, the ritual and above all the uncertainty of outcome. It’s a race everybody wants to win but few do.”

Tom Kristensen, the Dane who has won Le Mans nine times, more than any other driver, has said that although today’s drivers are afforded more protection than ever before, the inherent dangers of racing at night, constantly overtaking slower vehicles, can never be allayed. “There is nothing like it,” he explains. “Peering into the darkness, blinking, watching for the blue flags that indicate a slower car, and having to do this lap after lap after lap. It is like concentrating for a maths exam while at the same time fighting a boxing match.”

Until 1970 at the start drivers ran to their cars from the other side of the track. This was dropped when it became too dangerous – drivers often failed to fasten their seatbelts trying make a fast getaway. And it encouraged cheating. Mike Hawthorn, who won in 1955, simply started running before the flag fell. Nobody was ever called back because the race had to start bang on the hour. His rival Stirling Moss called out “cheating bastard” every time it happened. One year Hawthorn laughed so much he was the last to get his car started.

And while today’s Le Mans is more about overall victory than proving the resilience of the car, the two still go hand in hand. Something of the original intention of the first organisers holds true. Manufacturers are fully aware of the prestige victory brings. Even if the fans care little and thrill to the sports prototypes – all still road-legal – which will win the race, the likes of Aston Martin, Porsche and Ferrari who enter the slower classes in cars easily identifiable as the road-going versions on which they are based, do so because they seek commercial success away from the track.

Le Mans is now a global carnival attracting 250,000 supporters, a fifth of them British, a significant number of whom never even see a car raced, spending their time in the campsites and entertainment villages dining, drinking and partying. Author of The Le Mans 24-Hours Race, Mike Cotton says: “For the spectator, it’s a place for excitement and passion, but also for sightseeing, campfires, tiredness and cold. It is never less than an experience.”

What began as something more akin to a country fair is now a global jamboree. But for those with an eye on the past perhaps the nearest a modern-day spectator can come to the bucolic aura of that first race is to head out to the section of track located near Indianapolis and Arnage corners. Ignoring the modern machinery passing by you can sit beneath trees, awaiting the headlights that punctuate the hours before dawn and appreciate that, as it was in 1923, this is a race that challenges driver and car like no other.

Derek Bell, the Briton who shared three victories with Jacky Ickx and won five times overall says: “You can race all season, and win all season, and then you go and lose at Le Mans and for whatever stupid reason that’s all you care about.” Or, as the late Ken Miles, subject of the Matt Damon movie Le Mans 66, said less poetically: “The shit on your shoe you can’t wipe off.”

At 4pm on Saturday 10 June, as the cars growl and twitch their way through the final corner of the warm-up lap awaiting the green lights which will unleash that howling, cacophonic swarm of machinery into the first corner, leaving behind only the residue of crowd chatter, minds will probably not be focused on Lagache and Leonard, nor the race’s visionary founders Faroux, Durand and Coquille. Most people in attendance will likely never have heard of them. But maybe when the dust settles more than 24 hours later there’ll be time to reflect on what happened a century ago and how the intervening years have fashioned and moulded what is, to aficionado and casual observer alike, the world’s greatest motor race.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments