Faking death: Why do people go to such lengths to escape?

Who hasn’t fantasised about running away from it all and disappearing to some exotic locale? Faking death has a certain macabre appeal but, as Len Williams discovers, the realities of ‘pseudocide’ are rather less attractive

It was a tragic end. Arafa Nassib, 47, of Walsall, was killed in a car accident while travelling in Zanzibar. Documents showed that the British national died of a severe head injury in April 2016 while visiting family in Tanzania. Her death certificate was signed by a Doctor Mosi at Zanzibar’s Mnazi Mmoja hospital. The death certificate also mentioned the Bumbwini graveyard where Nassib’s body lay at rest.

But then things started getting strange. Detective Constable Daryl Fryatt of the City of London’s insurance fraud department says his team were contacted by Scottish Widows, Nassib’s life insurance company. Fryatt explains that when her 18-year-old son submitted the life insurance claim just a few weeks after her death, red flags started popping up.

Scottish Widows hired private investigators and sent them to Zanzibar (a pretty good gig by the sounds of it) to check up on the back story, Fryatt says. Although her death certificate was authentic, when the investigators visited the Mnazi Mmoja hospital, administrators told them that the doctor who had signed the paperwork couldn't have done so, since he wasn't in the country at the time. Then there was the matter of her body. On visiting the graveyard in Bumbwini, staff there had no record of a funeral or burial plot. Then there was the Zanzibar police. They had no record of a car-crash death on the date in question. “You would expect at least a forensics report and documentation surrounding a death like this,” says Fryatt. Yet none appeared to exist.

But most damning was when “we did some phone work on the mother” recalls Fryatt. By doing some call tracing, his department discovered Nassib (or at least someone using her phone) had called her son several times from Zanzibar after her supposed demise.

The motive behind Nassib’s fake death was money. She had got into insurmountable debts with “buy now, pay later” purchases which had racked up. Set to receive £136,000 from her life insurance pay-out, she seems to have concluded that this was the best way to escape her debts. “These are typically crimes of desperation,” Fryatt notes. She was eventually arrested after a sojourn in Canada staying with relatives (she flew on her own passport). But by that point the game was up; her son had already confessed to everything and when she returned to the UK, she was given a two-and-a-half year sentence.

Nassib’s tale is just one example of the many people who have committed “pseudocide”, or who’ve staged their own deaths in some other manner.

People do it for all kinds of colourful reasons. Take the case of Timothy Fletcher, a 16th-century businessman who wanted to see how many people would attend his funeral. Then there was the case of Arkady Babchenko, a Russian journalist and Kremlin-critic exiled to Ukraine who faked his own assassination in 2018 (including make-up gunshot wounds and a pool of pig’s blood) before appearing at the press conference to announce his death the very next day.

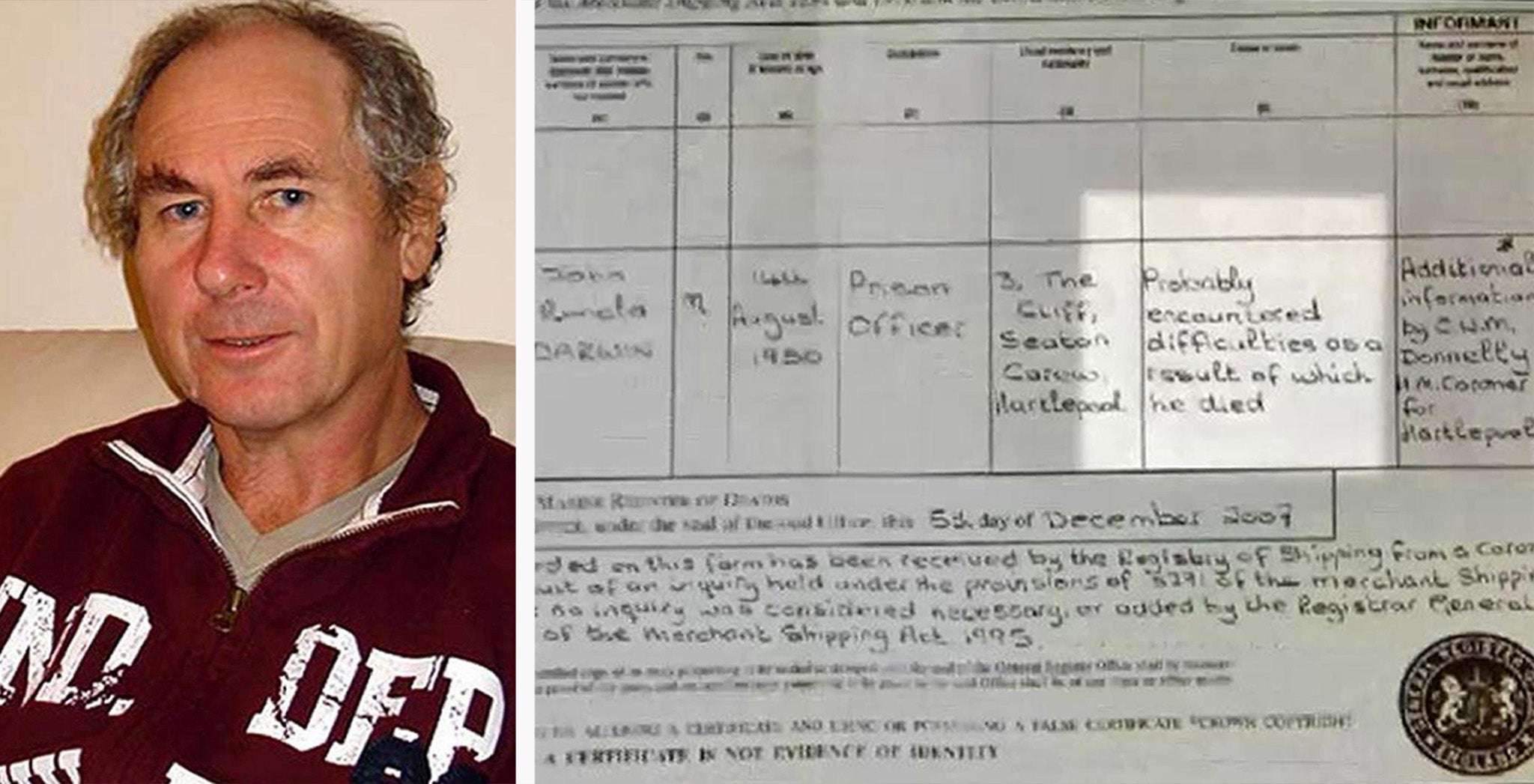

Babchenko’s staged death was part of a sting operation to identify a Moscow-backed hitman, who was allegedly out to get him. In recent years, the most famous British faked death was that of John Darwin, better known as the Canoe Man, who disappeared in 2002 while paddling in the North Sea in his red canoe as part of a plan to escape his debts. He slunk back to shore, changed his appearance and moved into a backroom of his own home, living with his wife for six years and travelling the world before being uncovered.

“Faking your own death is an opportunity to exploit and escape your problems,” reckons Dr Tim Holmes, an academic at Bangor University who researches fraud. While the more exotic fake deaths catch the eye, the majority tend to be driven by desperation (huge debts) or greed (the supposedly “easy” insurance money).

In the UK, people’s debts are usually written off when they die. So, if you can convincingly pull off your own death and disappear permanently, an accomplice can claim your life insurance while you hide out. All being well, the pseudocide will make good, perhaps living in a low-income country where they can get by on a few thousand pounds each year.

It's also a way to escape other problems, including the general grind of daily life. Unlike simply disappearing, where there's always a chance someone might potentially come and look for you, faking your own death can give you a complete break from your past. It’s also a means to escape difficult situations. In her entertaining book Playing Dead, journalist Elizabeth Greenwood explains that for women who are seeking to escape a violent partner or a stalker, faking their own death is sometimes the only option.

DEAD OR ALIVE?

Patrick McDermott

The boyfriend of Grease star Olivia Newton-John, McDermott disappeared on a fishing trip in Mexico in June 2005. While he has never been found, there is wide speculation that he faked his death to avoid bad debts and child support payments to his ex-wife.

Takashi Mori

In 1995 Mori faked his death with the help of his son so his family could live off his life-insurance policy worth $5m. Unfortunately for him, he was found very much alive 9 months later in Manila where he was arrested along with his wife and son.

Lord Lucan

Richard John Bingham, the 7th Earl of Lucan, disappeared in 1974 following the murder of his children’s nanny and the assault of his wife who identified her attacker as Lucan. Shortly after, his abandoned car was found with an empty bottle of prescription medication suggesting he had killed himself. It is rumoured, however, that Lucan faked his death.

Although pretending to have died and leaving your life behind seems a crazy decision, it's not as rare as you might think. Fryatt says the City of London Police’s life insurance fraud unit sees at least one or two such cases per year. That said, an insurance specialist I spoke to (who preferred not to be quoted directly) reckons that less than one in 100 claims for life insurance are false.

In some countries, there is a veritable industry in pseudocide. The Philippines, for instance, has a dubious reputation as a particularly good place to pick up a faked death package. For a few thousand dollars, one can purchase a death certificate, a new identity and even, shockingly, a corpse from corrupt morgue staff who can provide uncollected bodies (or indeed, body parts).

The problem for most faked deaths however is what Fryatt calls their “criminal naivety”. Most people who stage their own deaths assume that life insurance companies aren't going to conduct big investigations to find out if their death was authentic, especially if they die somewhere far away. He adds that most people who decide to go down this route do so out of desperation and with relatively poor planning. What’s more, few have criminal contacts that could help them with getting things like fake documents – and many don't even think to change their appearance. Perhaps the hardest thing is making a break with one’s past, especially family members. Faking your death is by definition final – yet many of them struggle to close off all contact with children, partners and relatives.

There are often tell-tale signs that someone is faking their own death. According to the insurance industry insider I spoke to, having a large amount of debt is almost always going to set off alarm bells if someone registers a life insurance claim. It doesn't take much to run a background credit check. Accidental deaths outside of the UK are also likely to raise eyebrows, as are those where no body can be found (while people often think that disappearing at sea is the perfect option, it's quite rare for accidental drownings not to wash up). It also looks suspicious if someone makes the life insurance claim within a year of taking the policy out.

Another telling difference is the content of suicide notes. Dr Jess Shapero, who has studied their content, says “the differences between real and fake notes tended to be in the “oddness” of fake notes: inconsistent spelling and naming, odd phraseology, logic, vagueness, and perhaps most salient, the melodramatic content. Of course, not all fakes had all, some, or even any of these things; and many real notes had some of them.”

“I think he damn well knew what he was up to,” says Julian Hayes, the author of a new book on his great uncle John Stonehouse. Stonehouse was a member of parliament for the Labour Party in the 1960s and 70s, whose life, fake death and reappearance read like something out of a bad spy novel. Hayes, who is a criminal lawyer, recalls the events surrounding his great uncle’s disappearance as a big factor in his childhood which was both “bemusing and entertaining”. It caused a major rift in his family and Hayes says his father was deeply hurt by his uncle’s ruse, refusing to ever speak to him again.

Stonehouse's story seems a classic case of pseudocide, combining the mix of narcissism, desperation and dishonesty that's required for someone to fake their own death. His troubles started while he was an MP and later a cabinet minister. It was the height of the Cold War, and Stonehouse had several meetings with Czech spies throughout the 1960s who were after information on British intelligence. Hayes reckons, on balance, that his great uncle did sell some secrets – although he mainly seems to have strung them along with information of little value.

However, in 1970, a Czech spymaster defected to the west and revealed that various members of the British elite had handed him information directly. While Stonehouse was never proved to have committed the crime, people started talking, and he was demoted from the shadow cabinet to the back benches (after Labour lost the 1970 election).

Stonehouse then decided to set up a number of import/export businesses to subsidise his MP’s income (a story that has a contemporary ring to it). Hayes’s father helped Stonehouse set the businesses up, and while successful to begin with, things soon started going wrong and Stonehouse began using “creative” accounting practices. His investors started to complain, and the Department for Trade and Industry began looking into his affairs. At the same time, Stonehouse was carrying on an affair with his secretary, and the high-profile spy cases and insinuations around his involvement with the Czechs were making life unbearable. “It was a perfect storm,” Hayes reckons.

DEAD OR ALIVE?

Samuel Israel

On 9 June 2008 former hedge fund manager Samuel Israel was supposed to turn up at prison, convicted of running a Ponzi scheme. Instead, his car was found in up-state New York with the words “suicide is painless” written in the dust on the bonnet. The police didn’t buy it, and low and behold Israel turned up a month later.

Stephen Kellaway

Inspired by John Darwin, Kellaway and his wife, Nelli, came up with their own plot. In 2008 Nelli reported her husband dead while visiting Russia. She then returned to Britain and presented the Russian death certificate to UK officials. It was another two years before he handed himself in, admitting he faked his death in an attempt to duck another insurance-fraud investigation.

Lenin Carballido

This politician was elected mayor of a Mexican village in 2013, three years after he was supposed to have died of diabetes. It turned out that he had in fact faked his death to escape rapes charges dating back to 2004, before running for election as a ‘dead man’.

Reading about people who’ve staged their deaths, I’ve sometimes found the decision darkly comic, and am even a little impressed by the audacity involved. But then there are the details which remind me quite how heartless it is. For example, to make his getaway, Stonehouse contacted his local hospital, telling them he needed a list of recently deceased constituents as part of a (phoney) plan to distribute money to their widows. Once he’d found two dead men of a similar age to him, he visited their widows, as their MP, feigning concern but really aiming to gather information about his new identities.

He then collected their birth certificates from the registry office and used them to apply for new passports. Stonehouse then travelled to Florida for business meetings in late 1974, staying at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach (made famous in the Bond movie Goldfinger). After meetings with business partners, he conspicuously told them he was off for a swim at the beach but would meet them that evening for drinks. Leaving a pile of clothes on the shore, Stonehouse swam out to sea before coming ashore further up the coast, collecting some dry clothes and his belongings. He then took several flights, ending up in Australia. Stonehouse may well have got away with his disappearing act, but for an eagle-eyed teller at a Melbourne bank who noticed the distinguished Englishman making several unusual transactions under two identities. Fraud was suspected and his true identity was eventually discovered.

“He never owned up to it and he never apologised,” says Hayes. “You have to remember the impact on the family, on his children and his former wife Barbara.” Left to believe Stonehouse had died, they’d mourned him, then discovered they’d been hoodwinked. Once on trial, Stonehouse opted to defend himself, claiming a form of schizophrenia which meant his decisions had been taken by an alternate personality. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to seven years in prison for fraud.

The problem with faking one’s own death is that, without a very sophisticated plan and potentially some criminal contacts, the whole process is a lot harder to pull off than many would-be pseudocides might think. And if you are trying to claim insurance money, an investigation is highly likely. In our CCTV-covered world, and the digital footprints we leave everywhere we go, truly disappearing is hard work. You've also got to have quite a lot of money at hand and the ability to start afresh and generate an income in your new life until the insurance money comes through.

But I also find myself wondering if it's something that most ordinary people could do. To completely disappear, leaving behind family, friends, your routine and your job, seems incredibly callous. I ask Dr Holmes if he thinks there’s a certain type of person who's more likely to fake their own death. Perhaps you need a narcissistic personality disorder, or even to be a sociopath?

However, Holmes instead points to “strain theories” in criminology. He explains that if you put enough pressure on someone, they might turn to crime in response. Some people are what is known as “retreaters”. If unable to meet their needs, they decide to retreat from society – dabbling in drugs, petty theft, or joining a cult. But then there is another kind of response to strain – becoming a criminal innovator. When faced with overwhelming challenges (debt, accusations of spying, angry investors, threats on one’s life, etc) they come up with creative criminal solutions – one of which would be to fake one’s own death.

So, if under enough stress, and with no obvious alternatives, perhaps more of us than we would like to admit might choose this way out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments