The story of rice: How a humble grain changed the world

Rice is one of the most widely eaten foods across the planet. Billions of people depend on it for their daily calorific intake and it has transformed civilisations, writes Len Williams

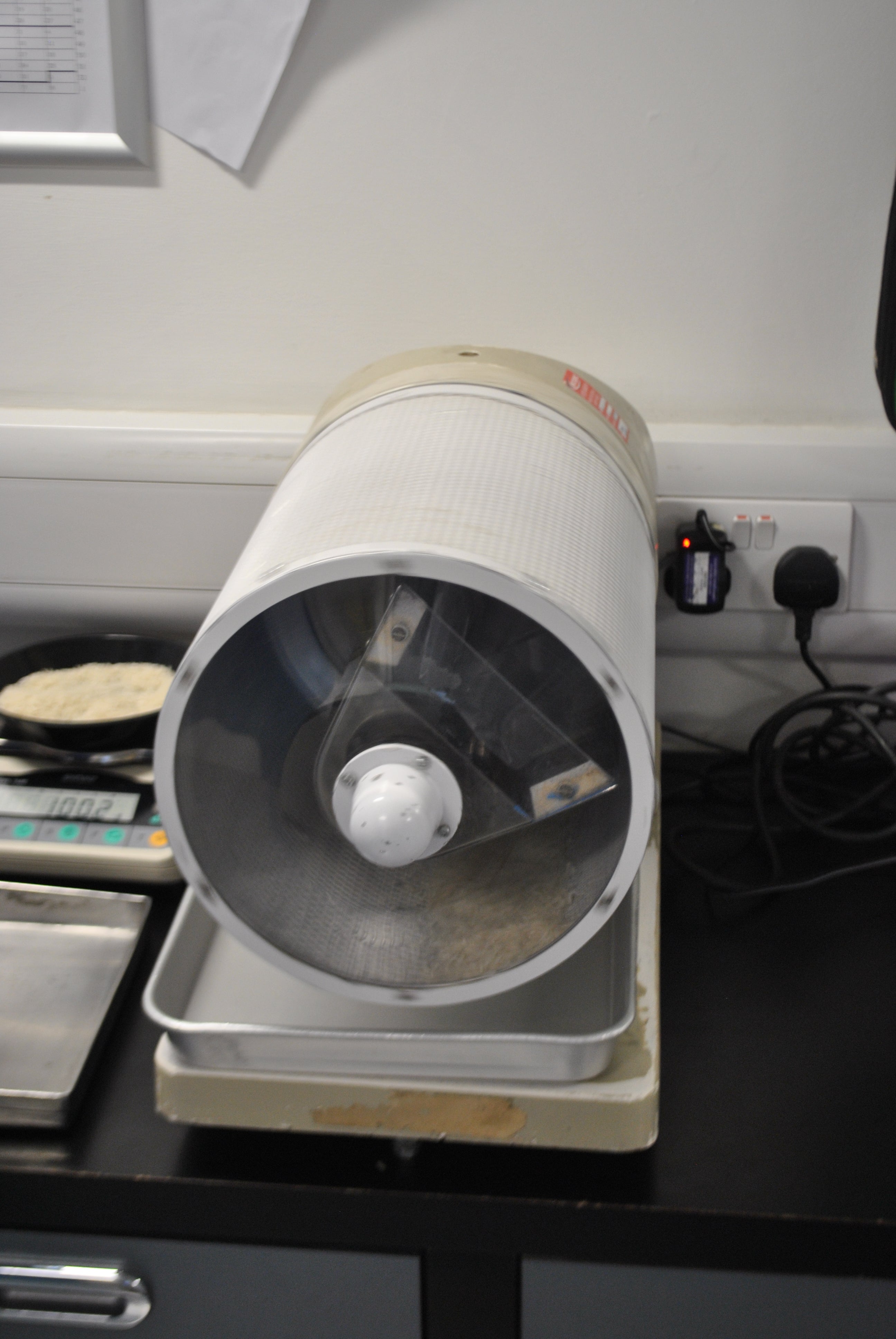

I am looking through a glass pane into the side of a machine where, every second, a waterfall of rice cascades past. Every now and then, an individual grain is thrust horizontally backward, blown out of the flow by a finely directed puff of air. High-powered cameras inside the machine can identify any discoloured grains and remove them from the flow, so that only smooth, uniform, white rice remains.

This processing is one of the final stages in a highly complex global industry that spans continents, millions of farmers, middlemen and consumers. I am being given a tour of a mill in east London owned and run by Tilda, one of the UK’s major rice importers and manufacturers. Minesh, the mill’s chief operator shows me how hundreds of tonnes of rice are held in Tilda’s silos, where they’re stored for at least one year before processing – like wine, rice improves with ageing.

The highly automated factory then brings rice from the silos to the mill where millions of grains are filtered to remove dust and stones. Once cleaned, the rice is milled, its brown husk removed. Next, it is polished and broken grains are separated, so only the full, desirable grains remain. Tilda then removes discoloured rice before finally packaging it up and shipping across the UK and to some 50 countries around the world. Minesh explains that there’s practically no waste from Tilda’s operations – the broken or discoloured grains are sold on to other industries, for animal food or even beer production.

After wheat, rice is the most widely eaten cereal on Earth, and is the staple food for an estimated 3.5 billion people worldwide – just under half the human population. Every year, some 480 million tonnes of the stuff come out of the world’s mills, and it is the primary source of income and work for about 200 million households. China and India are the world’s biggest rice growers, producing about half of global output together, while other south and east Asian countries produce much of the rest – although it’s grown on every continent except Antarctica.

This foodstuff is invaluable, providing a source of energy for billions of people, supporting economies, and playing a key role in many countries’ cultures. But it goes further. To understand rice, is, arguably, to understand the making of the modern world. So what exactly is this grain, and how did it come to change the world?

Oryza sativa and Oryza Glaberrima

Rice is an annual grass plant, of which there are around 22 species. Two of these, Oryza Sativa and Oryza Glaberrima, to use their Latin names, have been cultivated by humans. Oryza Sativa has the longest history; it originated somewhere in southern China and was first cultivated some 12,000 years ago. Oryza Glaberrima comes from West Africa, where it was first cultivated around 1,000 BC. Today, Oryza Sativa is by far the most widely eaten and produced, and there are some 40,000 cultivars (variations) of the crop.

Wild rice grows in shallow water and produces a naturally red coloured grain. Today’s cultivated rice plants tend to be taller – over a metre in height – and have been selected over thousands of years to produce a white grain.

Of the cultivars that are most widely eaten today, there are two main types. Long grain indica rice such as basmati and jasmine, which are longer, thinner, and have an aromatic smell. These are most common in south Asian and Thai cuisine. Then there is the more glutenous japonica rice, which tend to be rounder and stickier when cooked – which makes it perfect for sushi, as well as dishes like risotto.

Dr Dorian Fuller, an archaeological botanist at University College London, explains how rice would have first been cultivated in southern China. “The first step is the expansion of wild rice’s natural habitats,” he says.

Due to the need for shallow water and open environments away from shade, Fuller says, the early “farmers” would have increased the open wetland area by clearing other vegetation to encourage more wild rice to grow. This early cultivation and learning about rice would have been slow – this first step alone would have likely taken thousands of years.

To begin with, growers buy seeds, irrigate their paddy and let nature do its job. Depending on the type of grain and part of the world, rice might produce one crop per year or as much as three

Next, things got a bit more sophisticated. “We see the emergence of tools like spades that were made out of the shoulder bones of deer,” Fuller explains. Around 6,000 BC, people began developing digging tools to expand the area where the rice could grow. Then around 4,000 BC the first unambiguous paddy fields appear, according to Fuller. These would be just a couple of metres across, a small oval dug out that would allow early farmers to control water conditions, fertilise the paddy and drain it too. This controlled environment allowed the paddy to become more productive and produce more grain. By 2,500 BC, the first large scale paddies emerged, with complex walkways and channels – not a million miles from modern methods.

Fuller, whose archaeological work involves studying remains found at ancient settlements, explains that in southern China at least, people already had ceramics over 10,000 years ago. They would have used pottery to boil rice just as we do today, while steaming came a few millennia later. But how did rice go from these modest origins, to a cornerstone commodity of global trade?

From paddy to plate

Every morning at Tilda’s Rainham production site, Michel Saphy, a technical manager, taste tests the various types of rice the company produces. As part of my visit, I was invited to score the texture, colour, aroma and stickiness of various grains. As it turns out, rice isn’t just rice. Some were sticky, with plump grains that held their shape. Others were almost mushy. One type was long and thin, another shorter and particularly aromatic.

Part of the reasons Michel smells, swallows and scores the rice each day is that rice is highly absorbent. If held in physical proximity to other strong-smelling goods or chemicals, it can absorb that flavour. His job is therefore an important final stage in ensuring the company’s products meet its customers expectations.

Before rice reaches the plate, however, it goes through a hugely complex production process spanning the globe. Jason Bull is the director of Eurostar Commodities, a food importing business in West Yorkshire, who explains the entire farm to fork process.

To begin with, growers buy seeds, irrigate their paddy and let nature do its job. Depending on the type of grain and part of the world, rice might produce one crop per year or as much as three.

Once the plants have matured, the farmer will thresh it, and a local middleman will buy the crop directly from them. The middleman may work for a local mill, or they could bring the crop to market where it might be purchased by bigger dealers. In any case, the miller normally dries the grain – it has about 25 per cent moisture content when fresh, and needs to be less than about 16 per cent before milling. Once dried, the grain can sit in a silo for months or even years. At this stage, you have brown rice, which is edible but takes longer to cook. It is also higher in vitamins as the outer layer contains most of the nutrients.

The vast majority of the world’s rice is eaten within a few miles of where it was grown. But for export, Bull explains large sacks are packed onto pallets and shipped around the world before being distributed in destination countries by firms like his.

As a global commodity, rice – and its price – are deeply entwined with the vagaries of world trade. Bull, whose firm imports sushi rice from Italy, explains that rice prices in the UK have been hit by a perfect storm of Brexit-related customs, a growing taste for Japanese food – higher demand equals higher prices – and the pandemic.

Tilda also told me they are seeing similar global logistics challenges due to Covid-19. When lockdowns brough world trade to a halt, the planet’s container ships were prevented from charting their usual course. As a consequence, getting hold of freight to bring rice to the UK is much more expensive than in the past. One silver lining is that, because rice is usually aged for at least a couple of years, rice millers still have plenty in their silos for at least the medium term.

Have you eaten rice today?

In Mandarin, the greeting 你吃了吗 is sometimes translated as: “Have you eaten your rice today?” It’s the equivalent to “how are you?” in English, and shows just how deeply entwined rice is with culture, especially in the nations that produce and eat most of it.

Professor Francesca Bray is a historian and anthropologist at the University of Edinburgh, who has conducted research into agriculture in China and nearby countries. She explains that perhaps a more accurate translation would be “have you eaten your grain today”, since it really refers to the traditional grain eaten in different parts of the country historically, which could be rice or millet. Still, the link between rice and culture is significant in many places.

In certain countries, rice is deeply entwined with the national psyche. In Japan, Bray explains, the emperor plants, and later harvests, a little rice each year, as a symbol of how important the grain is to Japanese people. She explains that Japan has resisted the WTO’s entreaties to permit rice imports from other countries, arguing that rice is a cultural exception, so it should be allowed to subsidise its market and prevent cheaper foreign imports coming in. Japanese leaders have even claimed that the japonica strain of rice is most biologically appropriate for the Japanese physiology.

Rice, and the ways it has historically been produced, can also have profound effects on the ways societies develop. Again in Japan, Professor Bray points to research by anthropologists which link the country’s particular approach to capitalism and business management with the way rice was traditionally grown in the country.

From the words we use, to the landscapes of countries, to the structure of whole societies and the tides of global trade, the grain has had an extraordinary impact

Because access to water in Japanese villages was scarce and needed to be shared, researchers argue the social pressure to share and respect hierarchies was of utmost importance. They developed elaborate ways to manage the distribution of water, where individuals learnt to submit to the common cause or face ostracisation. It could be argued that Japan’s famously intense, hierarchical and self-effacing business culture is a direct descendent of its rice production methods. At the same time, historians have argued that industries such as milling, as well as credit broking and other institutions that grew up around rice in many nations were historically vital to the early development of capitalism and industrialisation across Asia.

In other places, the global rice trade can have devastating consequences. Bray points to studies in West Africa, where the Oryza Glaberrima strain of rice has been cultivated for some 3,000 years. In several countries in the region, growing rice was traditionally seen as “men’s work”, giving young men a sense of identity and purpose in their communities. However, in recent decades the market in some countries has been flooded by cheap Thai rice. This has proven highly disruptive to traditional social structures, forcing young men to migrate to cities or, in some places, even take up arms.

Going against the grain?

Eaten the world over, rice in its many variations is surely one of the most successful crops in human history. But it’s not without its controversies.

Perhaps the biggest issue for rice is climate change – both its susceptibility to shifting weather patterns, and its contribution to them. Rice farming depends on fairly predictable weather in most of the places it’s grown; monsoon seasons to provide rain or river flooding. Then long, hot seasons to grow. But with climate change disrupting weather patterns, producing rice could become harder, says Jason Bull of Eurostar Commodities.

But rice is also a contributor to global warming, accounting for about 12 per cent of global methane emissions (cattle, by contrast, generates about 40 per cent of methane), largely related to anaerobic decomposition during the production process. This is an issue, but firms like Tilda, which work directly with farmers, say they are trying to address this issue. Last year, Tilda told me, they conducted a trial with around 50 farmers they buy direct from to use a method that reduced methane emissions by 50-70 per cent. Still, a lot more needs to be done before rice could be a truly sustainable produce.

Rice is also criticised for its low nutritional value. When eaten in its white form, it provides very few vitamins or minerals. When people rely on it too heavily they risk deficiencies and health problems. Attempts to introduce more mineral enriched strains however, have often failed to take off, because of cultural resistance.

Rice is nice

The week before writing this article I went on holiday to the city of Granada in Spain, where bars have the very civilised custom of providing a free plate of food with each drink you buy, chosen at random for you by the barman. Sometimes it would be little more than a piece of ham on bread or a bowl of olives, but without a doubt the best tapas would be little plates of paella, Spain’s best-known rice dish.

While eating paella, I though about rice’s 12,000 odd years of history, and the pivotal role it’s played in world history. From the words we use, to the landscapes of countries, to the structure of whole societies and the tides of global trade, the grain has had an extraordinary impact. But this success surely wouldn’t be possible it if weren’t for the simple fact that it is so incredibly versatile when it comes to cooking and eating.

And with that thought, I would eat my little plate of paella and order another round.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments