Should we really be living communally?

Living in nuclear families, or even alone, is a relatively recent phenomenon in human history. Len Williams asks if this is really the answer or if ‘intentional communities’ would make us happier and healthier

I’ve just had my first anniversary of living alone since leaving my childhood home. After 13 years living with (I estimate) 59 people at 19 properties, in six cities on three continents, it’s been paradise. There was the flatmate who gave me scabies. The couple who’d frequently have loud sex in the next room while I was eating breakfast. A man who went by the name “Sheep”, who’d play techno at 3am. No more difficult personalities to deal with, no more queues for the shower, waiting for people who leave their clothes to marinate for days in the washing machine, no more sinks piled high with plates slathered in dried pesto (I was of course a perfect flatmate).

But then there are the things I miss. Chatting over breakfast. House nights out, staggering home together with kebabs. Sunday roasts, and always someone there to have a natter, share a cup of tea or simply watch the box with. And during the third lockdown in 2021, I, like many others, started craving more interaction. There’s only so much company you can get from box sets. And I started to wonder if living alone is the right way to live at all.

Because throughout almost all of humanity’s history we’ve lived in tight-knit social groups. While all but a handful of true hunter-gathering societies still exist today, for tens of thousands of years that’s the only way we lived. Even when humans began living in settlements, living under one roof with one’s extended family, community, even servants, has always been the norm. Yet in just a couple of centuries, our living situations have gone through an immense transformation, and it’s now perfectly normal to live alone during youth and old age. And, in the west at least, the immense, and exhausting, responsibility of child-rearing tends to be left to a couple, and often just an individual.

While there aren’t any definitive figures, anecdotal evidence seems to suggest a growing number of people have been wondering just the same thing, especially since the beginning of the lockdowns. Interest in “intentional communities”, a term used to describe all manner of communal living scenarios, seems to be on the rise. What draws people to living in this way, how do people navigate the ups and downs of life in larger groups, and does it really make you happy?

Life in common

“I’m never lonely. In fact, as we speak, one of my neighbours is downstairs putting handles on a cupboard for me,” says Emma Sutherland, an artist and teacher who lives in an intentional community in Essex.

Sutherland moved into her three-bed home at the purpose-built Cannock Mill Cohousing in late 2019. Located by an old mill with its own pond, the site is home to 23 properties where around 30 people live. Each house is self-contained but many other amenities are shared and, pre-pandemic at least, members would eat together several times a week in a communal mess. Sutherland has enjoyed the experience thoroughly so far.

The idea of communal living was that by pooling resources everyone could ‘afford to eat, have lots of sex, have a nice place to live and look after each other’

Living in the community brings all sorts of benefits, Sutherland says. Members organise days out together (she runs the cycling group), people garden together and can join a car-pooling scheme, reserving communally owned vehicles if they ever need to make a trip. The social side of the set-up is certainly a big part of the appeal. “There’s always someone on the WhatsApp group asking if anyone fancies a cup of tea,” she explains, and “if you’re ever ill, people will bring soup or medicine over”. She adds that “it never feels like too much” and that she maintains her privacy.

Sutherland explains she was drawn to living in a communal setting after her youngest son left to go to university. Sick of the cold, draughty terrace house in Brighton where she lived previously, Sutherland came across Cannock Mill, which is built to the highest sustainability standards with a “passive” design, meaning it requires minimal energy to heat. After attending some meetings and getting to know other residents, she took the plunge.

This is just one example of an intentional community in the UK today. There are hundreds of such communities, which can extend from relatively conventional setups with private homes on a shared site (like Cannock Mill) through to religious groups, back-to-the-land idealists or off-grid anti-capitalist groups that reject all forms of ownership. There’s more that separates than unites many of these groups, but what they have in common is a notion of shared space, costs and, to differing extents, property.

Bill Metcalf, a scholar at the University of Queensland, Australia, and an expert on communal living, describes the way intentional communities have evolved over the past few hundred years. In Western societies, at least, “the original communal groups were monks and nuns” he says, and almost all early intentional communities were religious in some manner.

They tended to be religious breakaway groups, and many had a charismatic leader. These groups had the “advantage” of being bound together by a shared belief, and the thing they were rejecting – be that the Catholic Church, the Church of England, Lutheranism or something else. Some are still going today. The Shakers, for instance, a breakaway Christian sect founded in England in 1747, still has one commune operating to this day in the United States.

Metcalf explains that around the turn of the 20th century, a growing number of communes took on a more political and economic shade. Often anti-capitalist by nature, they chose communal living because “while they had no choice to own things, if they could own them collectively” they could challenge the system.

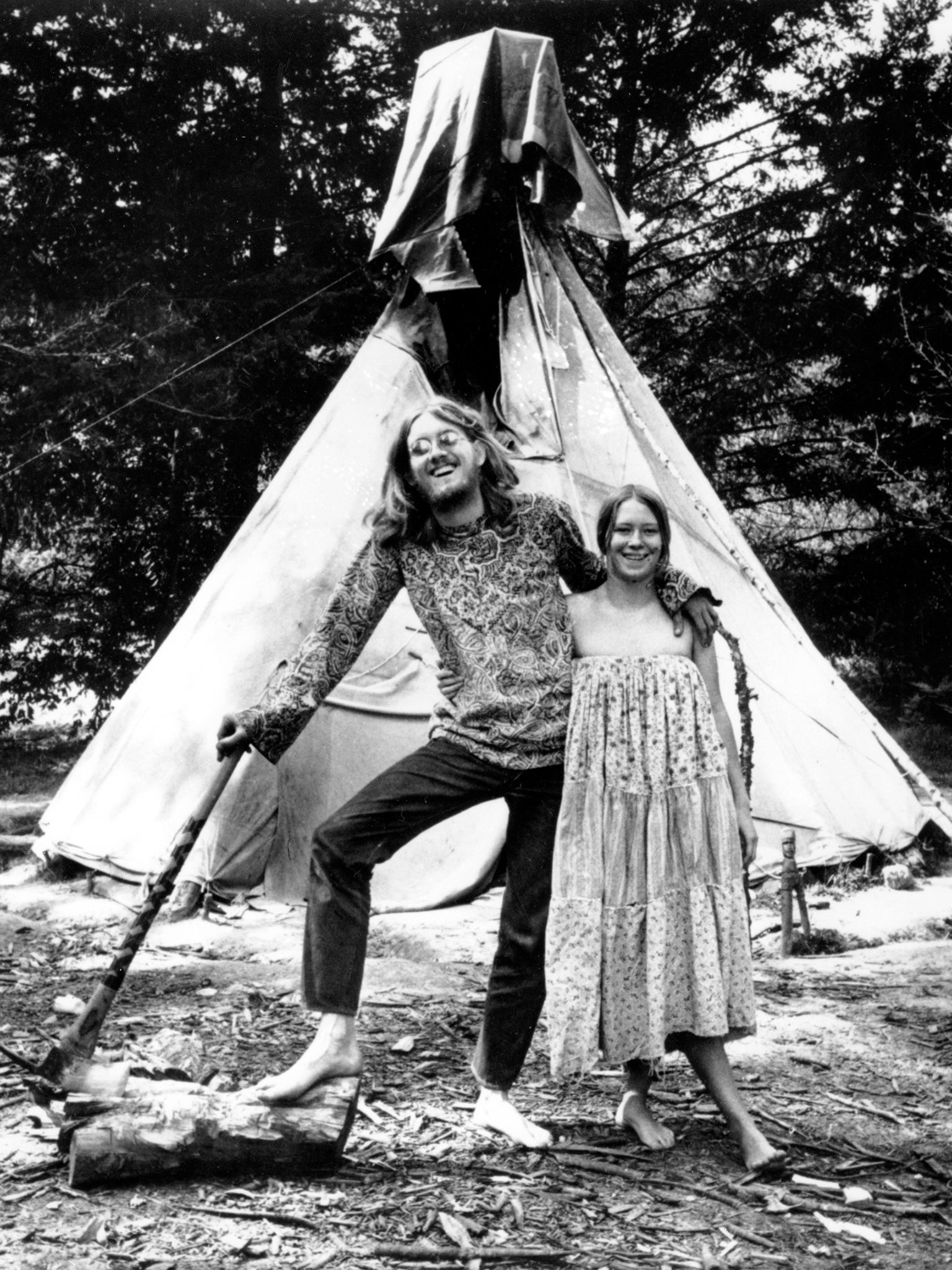

Then from the 1950s Metcalf says the contemporary movement began. Today, many people who live in communal settings eschew the word “communes” due to the negative connotations which emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s around this form of living.

“A lot of them were founded by dropouts and the idea of ‘let’s have a great time’,” Metcalf explains. The idea of communal living was that by pooling resources everyone could “afford to eat, have lots of sex, have a nice place to live and look after each other”. But he notes many were “horribly sexist” and there was plenty of drug use in the movement. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many communes of the time didn’t last more than a few years.

Since then, Metcalf says the movement has evolved again, to be much more environmentally oriented. Since living in groups with many others uses less energy and requires less food, it offers a more ecologically sound approach than living in smaller groups or alone.

Perhaps the most recent development in this movement is the emergence “cohousing” (such as Cannock Mill in Essex). This approach began in Denmark, Metcalf says, but has grown in popularity around the world. Individuals or families come together to buy land and build private units while sharing a communal eating area, vehicles and resources, such as washing machines. Within this subgroup, the fastest growing model is “senior cohousing”, where elderly people who wish to live with others will buy a flat in a shared building. It’s not a million miles from elderly residential care, but the place is owned and managed by the people living there, rather than an external company.

Love thy neighbour

People come to live in communal settings for all sorts of reasons and, as Kirsten Stevens-Woods, a researcher at the University of Cardiff puts it, “there’s a type of intentional community for almost anyone”. She has interviewed many people living in these communities and notes that there is often a utopian element in people’s decision to live in them. “They’re experimental spaces to test out different ways of being.” For instance, people might have met through social movements like Extinction Rebellion or membership of the Green Party and want to put green principles into action.

If you live in a community, there’s no need for everyone to own their own washing machine, cook their meals for one, buy a car, vacuum cleaner, power tools, or whatever else

But the utopian element isn’t essential. Stevens-Woods notes that it’s often a coming together of likeminded people or a group of friends who say: “wouldn’t it be great if we could all live together?”

Chris Coates, who has lived in two intentional communities at different stages of his life, explains how he got involved. While living in London squats in the 1970s, he became friendly with a group that eventually found a property to buy in Burnley. “At the time property in Burnley was absurdly cheap; the group bought a terrace house for £50 after a whip around”. The group he lived with renovated different properties, but he spent about 20 years living there before eventually moving out with his partner and son.

Later, with a group of likeminded folk, Coates helped set up and build Lancaster Cohousing, a development near Lancaster. The development hosts 41 houses, all built to the highest sustainability standards, which has been running for close to a decade. Coates also helps run Diggers and Dreamers, a website that publishes listings of intentional communities in the UK.

Meanwhile, Andy Thorne, an architect who lives at Cannock Mill Cohousing, and whose wife Anne, also an architect, designed the site, explains that their journey to living in an intentional community simply began while talking with friends. “The first conversations were about our parents and the issues of old age and loneliness. We wondered if there are better ways to think about living,” Thorne tells me.

Regardless of how people end up living in these communal settings, there do seem to be many benefits. One thing highlighted by everyone I spoke to is the cost of living. With shared energy, cars, food, and so on, people’s outgoings are much reduced. Emma Sutherland, who lives in a three-bed home at (the admittedly new and top-grade) Cannock Mill Cohousing, reckons her entire gas bill for last year was no more than £150.

There’s the environmental side too. If you live in a community, there’s no need for everyone to own their own washing machine, cook their meals for one, buy a car, vacuum cleaner, power tools, or whatever else. That means less consumption and less waste.

But the biggest benefits are surely interpersonal and social. Bill Metcalf, the academic from the University of Queensland, notes that in many communities “there’s some music or cultural event almost every night of the week”. There is also usually someone who knows about medicine, how to fix a broken computer, mend something, or lend a hand.

While some intentional communities are actively trying to encourage greater diversity, it does seem to attract a certain type

Living communally seems to be good for people too. Kirsten Stevens-Wood from Cardiff University mentions that the older people in intentional communities “do seem to be incredibly healthy if we compare them to people of the same age across the board”, which could have something to do with the lack of social isolation, communal eating and having people to check in on you.

Bill Metcalf also points out that “children fit in really well”. Most studies have been done in Israel’s Kibbutz communes, but suggest intentional communities offer a rich environment for kids. There are many people to learn from and an expanded group of brothers and sisters to play with.

This all seems very nice. But, having lived in a pretty good number of flat shares myself, I can’t help but wonder if communal living is as ideal as it sounds.

“One thing I would say,” notes Stevens-Wood, “is that it can be very intense.” The researcher has spent a great deal of time studying intentional communities, spending stints living on these sites. It is “the world’s most intense personal development programme that never ends”. Living in a community requires continually considering others, navigating their personal space and compromising. “When I was there I loved it, but when I got home it was so nice to slob out on the sofa and not have to think about other people!”

An awful lot of communards are highly educated middle-class people, Stevens-Wood adds. While some intentional communities are actively trying to encourage greater diversity, it does seem to attract a certain type.

It’s also not easy to start an intentional community. Andy Thorne says the original discussions that led to the creation of Cannock Mill began in the late 2000’s with people finally moving in in 2019. The design and build were surely helped by the fact that people involved had professional experience of architecture, finance and so on. Finding a site, getting planning permission and funding is challenging, and Stevens-Wood reckons that for every 100 groups that come together to try creating such a community, as little as one will ever break ground.

Getting into an intentional community isn’t altogether easy either. There’s often an interview process, with existing members understandably keen to live with people who share their values and approach.

Chris Coates who runs the Diggers and Dreamers website suggests that people interested in becoming a communard should try visiting a variety of sites to get a feel for what it’s like and find one that’s suited to them.

You wanna live like commune people?

“What you often notice is that the group that doesn’t cope so well [in intentional communities] are those from their late teens up to their mid-30s,” says Bill Metcalf of the University of Queensland. “They often find it inhibiting.” With communal life’s requirements to be responsible and always think about others, people in early adulthood might be more inclined to live alone or in smaller groups.

One of the best flat shares I ever had was in my final year at uni. We were seven close friends living in a mouldy house in Leeds, and I always remember it as the year of my life I laughed the most. As we approached the end of that year and realised it would all finish soon, we often spoke about how nice it would be to keep living in a big group. It never worked out that way and, with the ups and downs of a decade of flat shares, I can’t say I’m ready to give up solo life just yet. All the same, with its social, financial and environmental benefits, I can certainly see why communal living appeals.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments