China’s economy is in trouble – and Beijing appears powerless to do anything about it

After years of booming economic success, we can no longer rely on China to rescue the rest of us from weak growth, writes Chris Blackhurst

For the past few decades, one of the great world stories has been the seemingly unstoppable rise of China.

Less than four decades ago, its income per head was less than India’s. Now, China’s has comfortably surpassed it, becoming the second-biggest economy in the world along the way.

More than that, China is the engine of global prosperity. Dhaval Joshi of BCA Research calculates that China generated a staggering 41 per cent of the world’s growth in the past 10 years, almost double the 22 per cent contribution from the US and swamping the eurozone’s 9 per cent.

“Put another way, of the 2.6 per cent real growth rate of the world economy through the past 10 years, China has generated 1.1 percentage points, while the US and euro area have generated just 0.6 points and 0.2 points respectively.”

China’s economy has been consistently growing at the rate of 8-9 per cent a year, far ahead of anywhere else. Suddenly, as the world is experiencing a seismic shock, China’s growth rate has slumped to half that.

China’s consumer prices are falling and its property companies, responsible for much of its spectacular growth in construction, are teetering. Exports are down, youth unemployment is reaching numbers that have caused Beijing to cease publishing them. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index has turned bearish, down more than 20 per cent since January. The Chinese yuan plummeted to its lowest level in 16 years, forcing the central bank to make its biggest currency defence on record.

Gulp. Suddenly, China is not what it was and not what we were used to. We can no longer relax, safe in the knowledge that at least one economy would pick up the slack and forge ahead.

Today, China’s contribution to global growth is faltering, down to 0.5 per cent. Some economists say China’s growth could slip further still to 2 per cent, to precisely the sort of humdrum levels experienced by the US and others.

In short, we can no longer depend on China masking weakness elsewhere. At the same time, given the sharpness of the fall, China has itself become a problem.

With its new economic clout came political muscle. China now occupies a position on the global stage equal only to the US.

In the West, we were critical of its seeming friendliness towards other nations, accusing Beijing of pursuing financial imperialism, using its wealth to gain strategic advantages all over the planet. There was the Belt and Road Initiative and heavy investment in Africa, Australia, New Zealand and the Caribbean. Several of the world’s most valuable – and scarce – commodities fell under China’s control.

In the UK, while critical of China’s human rights record and wary of its true intentions, we nevertheless accepted Chinese ownership of some of our best-known companies and properties.

Whatever China was really up to, it was the nation that stepped into help across large swathes of the world where the West did not. Look at Sri Lanka, bailed out by Beijing, but now in its thrall (it holds almost 20 per cent of Sri Lanka’s debt).

China’s positioning as an alternative to the US was confirmed when countries positioned themselves after Russia invaded Ukraine. A substantial number rejected the anti-Russian line of the UK, US and European Union, deciding instead to side with China – resulting in Russia being able to trade freely and efforts to level punishment via western sanctions have largely been ineffective.

Externally, the global tectonic plates have moved – the US and the dollar no longer call the international shots. A new power bloc has arisen, of Russia, India and China, with China very much pulling the levers.

Internally, too, China is a nation transformed. Living standards have soared, people have largely been brought out of poverty to a degree scarcely thought possible not so long ago.

Now, though, for the first time, serious doubts about China’s ability to continue performing at this exalted level have been raised.

To put this in context: when the global financial meltdown struck in 2008, it was China that led the world to recovery, launching the largest stimulus package; when Covid hit, China was the only major economy not to go into recession. The safety net China provided has vanished.

For all it is bestriding the world stage and presenting itself as friend and saviour, China remains a rigidly closed country, totally subjected to the authoritarian grip of the Communist Party.

Its rulers looked at what occurred in other countries and did not fancy what they saw. Unlike the Soviet Union, which went down the route of openness and transparency under Mikhail Gorbachev, China’s leaders stopped far short of political reform.

They witnessed what took place in the Soviet Union and most certainly did not follow Gorbachev with their own version of glasnost. In China, power remains firmly with the Communist Party.

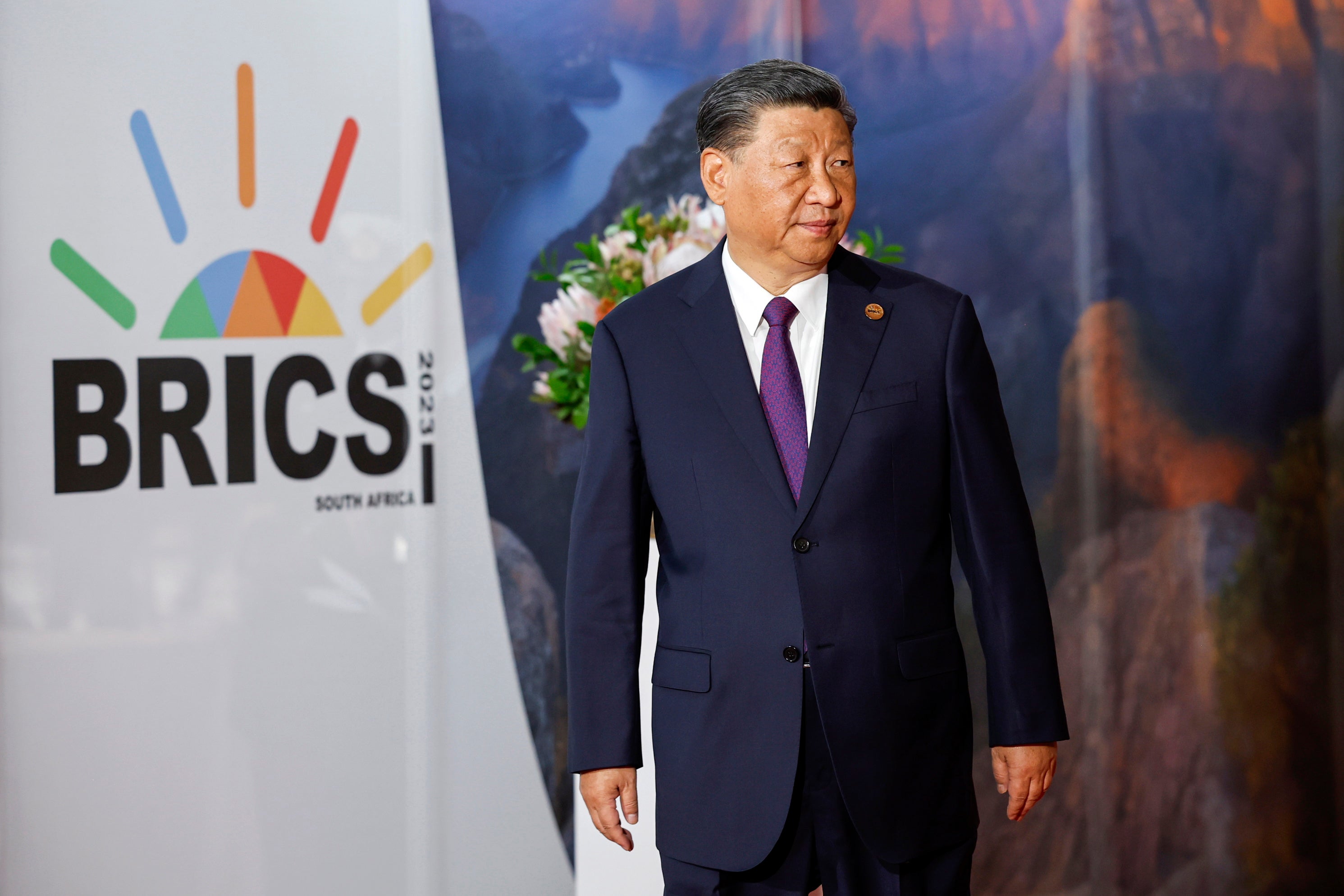

Maintaining that iron control is the overriding priority of President Xi Jinping, far ahead of anything else and at whatever cost. As part of that desire, China continues to lavish expenditure on building up its military prowess, to a degree that is both baffling if it is not used and terrifying if it is.

It was that objective that saw China impose the fiercest of Covid-19 lockdowns. The toll those measures extracted, socially and financially, were enormous. Local government ran up huge bills and debts in the absence of economic activity.

It may have suited President Xi, however, to keep the country battened down, its citizens effectively imprisoned in their homes, until he was safely appointed for a third term.

Xi has exhibited a wobbly nervousness. Last October, his message at the 20th National Congress focused on the lofty ideals of common purpose, higher quality development, a global agenda and peace.

A month later, there were demonstrations opposed to the onset of the harsh lockdown. These led to a typically forceful crackdown. Once it felt able to, with the ending of the pandemic, Beijing dropped its tough stance, and reversed the policy, declaring a sudden and unexpected reopening.

That now smacks of a panic measure. There was a brief flurry in consumer spending but doubts were setting in. What Beijing knew was that debt had been steadily climbing during the pandemic. It was high before, now it climbed higher.

Worryingly, it’s become clear that China is in no position to fight its way out of a corner, as it did in 2008. Indeed the cost of that move is still being felt, part of the colossal borrowing mountain that has built up.

What this means is that Beijing appears powerless instead of powerful, unable to make the bold moves that would end the crisis and spark recovery.

Lots of small measures have been forthcoming but nothing of the magnitude the situation demands. Xi gives the impression of someone whose hands are tied. He should be punching, but he seemingly can’t or is unwilling to, because that entails running up more debt and putting greater pressure on public services, which may risk further unrest.

Continuing poor relations with the US and some of its allies have not helped. China’s ability to manoeuvre is impaired.

There’s also the knowledge that the country’s population is shrinking. China’s growth rate is set to be slower and more erratic than in the past.

It is not a time to panic but to recognise this shift. Instead of taking China’s might for granted and counting on its economic weight and investment, the world should get used to a different China. Still powerful, still with tendrils everywhere, but reduced.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments