Books of the month: From Alan Bennett’s House Arrest to Hamish McRae’s The World in 2050

Martin Chilton reviews six of May’s biggest releases for our monthly column

As a banana-a-day muncher, I admit I was intrigued by a fact box called “Think you know bananas?” in Alex Renton’s entertaining 13 Foods That Shape Our World: How Hunger has Changed the Past, Present and Future (BBC Books). Turns out, I’ve been yellow-bellied in my fruit adventures, never having even tried any of the thousand varieties that are neither yellow nor even banana flavoured. The silk or tundan type, for example, grown in west Africa, has a tangy hint of apple. The most intriguing-sounding variety, though, is a red one that has “a faint raspberry flavour”. I bet that causes a few slip-ups in blind tastings.

Literary figures played a key role in some of the songs of Radiohead, and Thom Yorke has paid tribute to the inspiration of writers such as Ben Okri. The band were also influenced by Kurt Vonnegut’s 1963 science fiction novel Cat’s Cradle when composing their song “Nice Dream”. The Vonnegut link is one of the hundreds of intriguing facts in a new biography of the band, Radiohead: Life in a Glasshouse (Palazzo Editions), written by John Aizlewood, a music expert and editor of Q magazine in its heyday. Covering more than three decades, the book is a must-have for fans of this influential group.

A timely, albeit troubling, read is Yevgenia Belorusets’s Lucky Breaks (Pushkin Press, translated from the Russian by Eugene Ostashevsky), which is a collection of vivid stories by a Ukrainian photo-journalist, looking at recent events through a feminist lens. The book focuses on women affected by the war in east Ukraine, dealing with Russian military activities that pre-date the current invasion. The author’s search for sincerity shines through moving tales of displaced women. Lucky Breaks also offers a reminder that the truth is never pure and rarely simple.

Lena’s story, about a friend who was randomly punched in the face by a man simply because she was singing, prompts the woman’s confession that, “I’ve never felt any sense of security in Ukraine. Even in our Sumy, though it’s not as big a city as Kyiv or Kharkiv, it wasn’t safe for a girl or women there, especially if she is walking home in the evening, even if she lived in the city centre.”

May is a month full of varied, enticing fiction. I enjoyed the outlandish humour in Deesha Philyaw’s National Book award shortlisted short story collection The Secret Lives of Church Ladies (One). My favourite tale was the Florida-born author’s clever dissection of hypocrisy in “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands”, in which the protagonist, a woman who deliberately sleeps with pious married men, lays down guidelines that allow the cheating men to continue presenting a false face to the world, letting them they carry on “leading the Boy Scout troop and serving on the deacon board at church”.

Desire is also a theme of Maggie Shipstead’s cracking story “Angel Lust” (a term used to describe the eerie sight of a corpse with an erection), one of 10 stories in her splendid collection You Have a Friend in 10A (Doubleday). Another amusing novel is Fiona Vigo Marshall’s satire of the publishing industry, The House of Marvellous Books (Fairlight Books) – and one can only hope that the fictitious email from one publishing executive, requesting that staff refrain from the unnecessary expense of calling the speaking clock, is based on a real warning.

The most unsettling novel this month is Lacuna by Fiona Synckers (Europa Editions), a riveting feminist response to JM Coetzee’s novel Disgrace, one that puts Lucie Lurie, the victim of sexual assault in that acclaimed South African novel, at the centre of the story.

I would also recommend Louise O’Neill’s IDOL (Bantam Press), a punchy story about an online influencer and the ambiguous nature of truth. Sara Nović’s True Biz (Little, Brown) is a beguiling coming-of-age tale set in a residential school for the deaf. The Swimmers (Gallic Books), a debut novel by New Zealand author Chloe Lane, tackles the subject of assisted dying with wit and pathos.

David Park’s novels are always elegantly written and I liked Spies in Canaan (Bloomsbury), a story about the redemption of a retired man whose past in Vietnam catches up with him. The Perfect Golden Circle or The Strange Rites of an English Summer by Benjamin Myers (Bloomsbury Circus) is a gorgeous tale of friendship, set in 1989 and based around the crop circle shenanigans of two traumatised Falklands war veterans. Anyone interested in the art of translation will be engrossed by Translating Myself and Others by Jhumpa Lahiri (Princeton University Press).

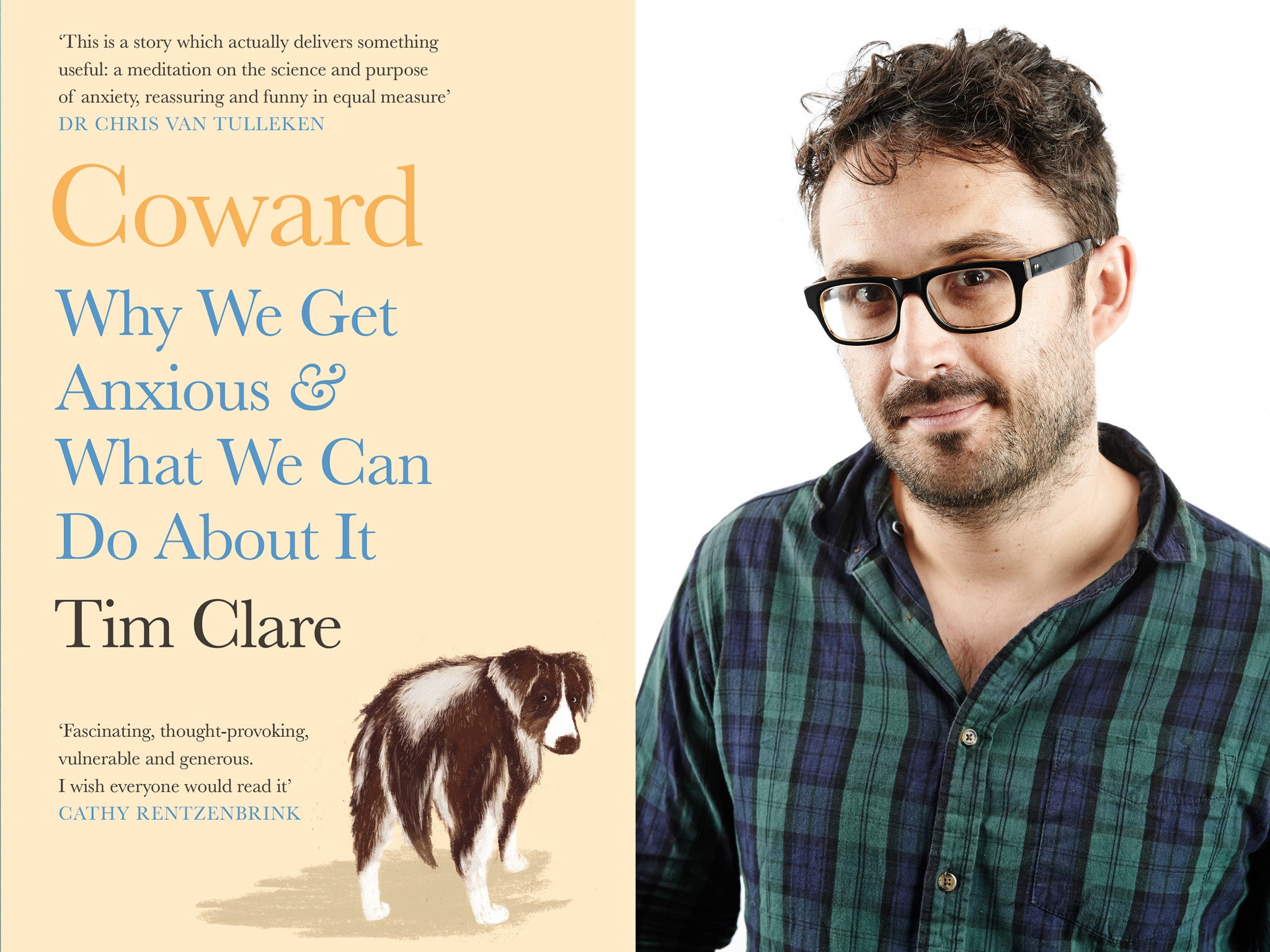

Finally, a recent survey found that one in three adults believe their mental health has deteriorated over the past year. In her poignant new collection The Chalk Butterfly (Cinnamon Press), Jane Monson offers some profound and delicate explorations of the tipping points of emotions, including how climate change can damage our mood. The current stresses and strains of the world are also the subject of Tim Clare’s guide to anxiety, one of six non-fiction titles reviewed in full below.

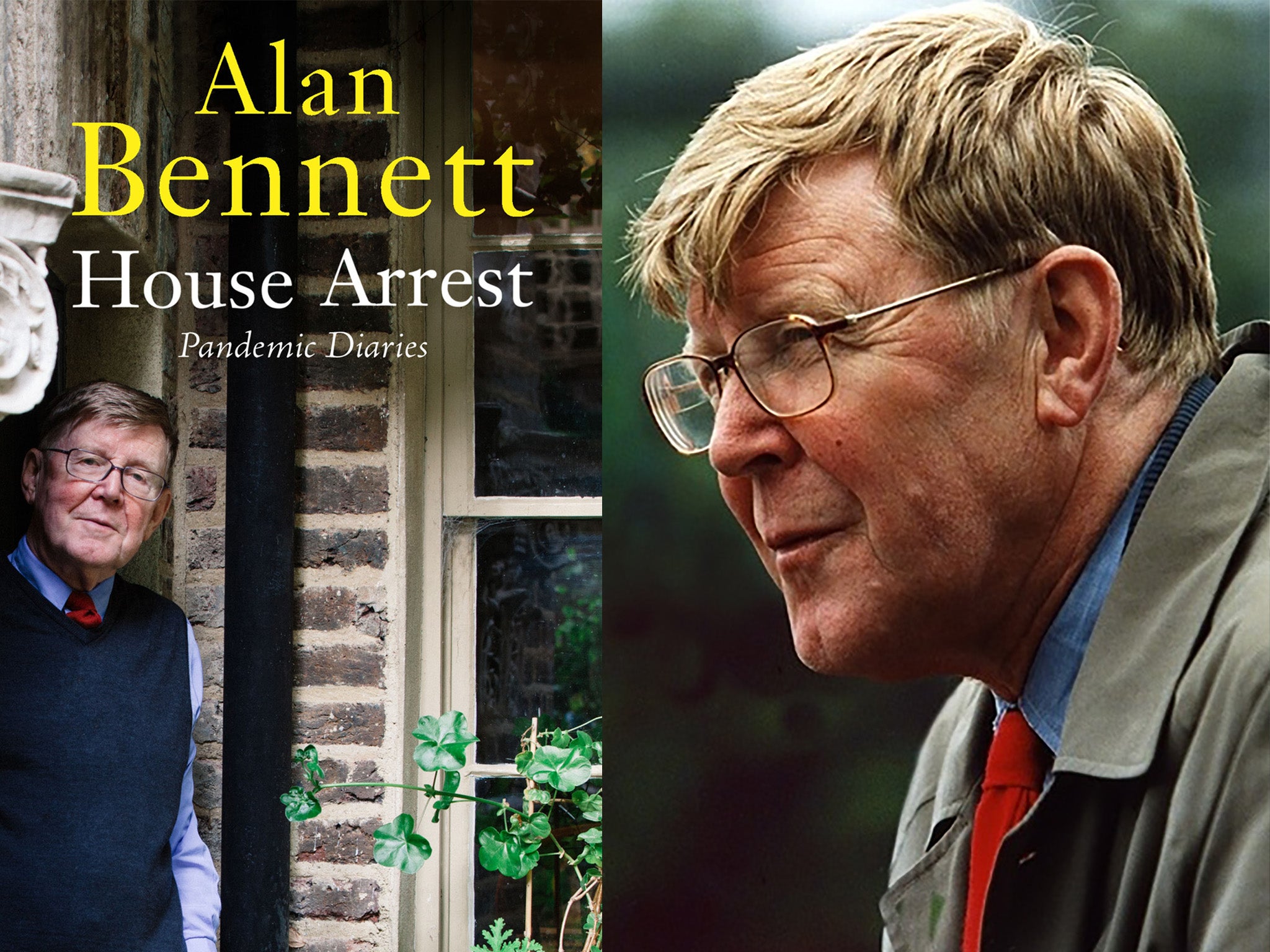

House Arrest: Pandemic Diaries by Alan Bennett ★★★★☆

“How do I define history? It’s just one f***ing thing after another,” answers one of the students during a mock interview in Alan Bennett’s award-winning play The History Boys.

In House Arrest: Pandemic Diaries, the sparklingly sardonic Yorkshire author, who turns 87 in the week of publication, offers his unique take on the recent dismal patch of history we’ve all struggled through – as he reflects on enforced confinement, and much more besides.

The book contains random literary barbs (“the one person who would not be washing his hands every five minutes is WH Auden”; “Graham Greene’s was the limpest hand I’d ever shaken”) and withering assessments of Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. There is also a charming account of making a new Talking Heads production during lockdown.

The publication is a mere 49 pages, but it is crammed with anecdotes, especially one about his father’s sudden enthusiasm for fishing. There really is no one like Bennett, as this small gem demonstrates.

‘House Arrest: Pandemic Diaries’ by Alan Bennett is published by Profile Books on 5 May, £6.99

Coward: Why We Get Anxious & What We Can Do About It by Tim Clare ★★★★☆

If you have an inbuilt aversion to self-help books – and I am reminded of the old joke about buying a book on how to overcome procrastination that you haven’t got around to reading yet – then it’s understandable how yet another one about the modern plague of anxiety is enough to give you the nadgers.

However, and it’s a big however, writer, poet and podcaster Tim Clare’s Coward: Why We Get Anxious & What We Can Do About It, about learning to face things that make you uncomfortable, is a clever blend of memoir, science and useful advice.

“When you tell an anxious person, ‘There’s nothing to worry about’, the message received is ‘You’re on your own,’” Clare declares, something that will strike a chord for those of us who recognise why our own hypervigilance is a burden.

I enjoyed Clare’s reflection on past psychological studies – including what happened in a 1968 experiment in which a waiting room was gradually filled with smoke – but what really resonates is his honest account of his own panic attacks and what it is like to try to come off sertraline. It’s good to read Clare’s take on medication, an important subject given that the number of people in the UK using drugs to combat anxiety is soaring, particularly within the 18 to 34 age bracket.

Coward is a brave and moving book – one that offers lots of practical help.

‘Coward: Why We Get Anxious & What We Can Do About It’ by Tim Clare is published by Canongate on 5 May, £16.99

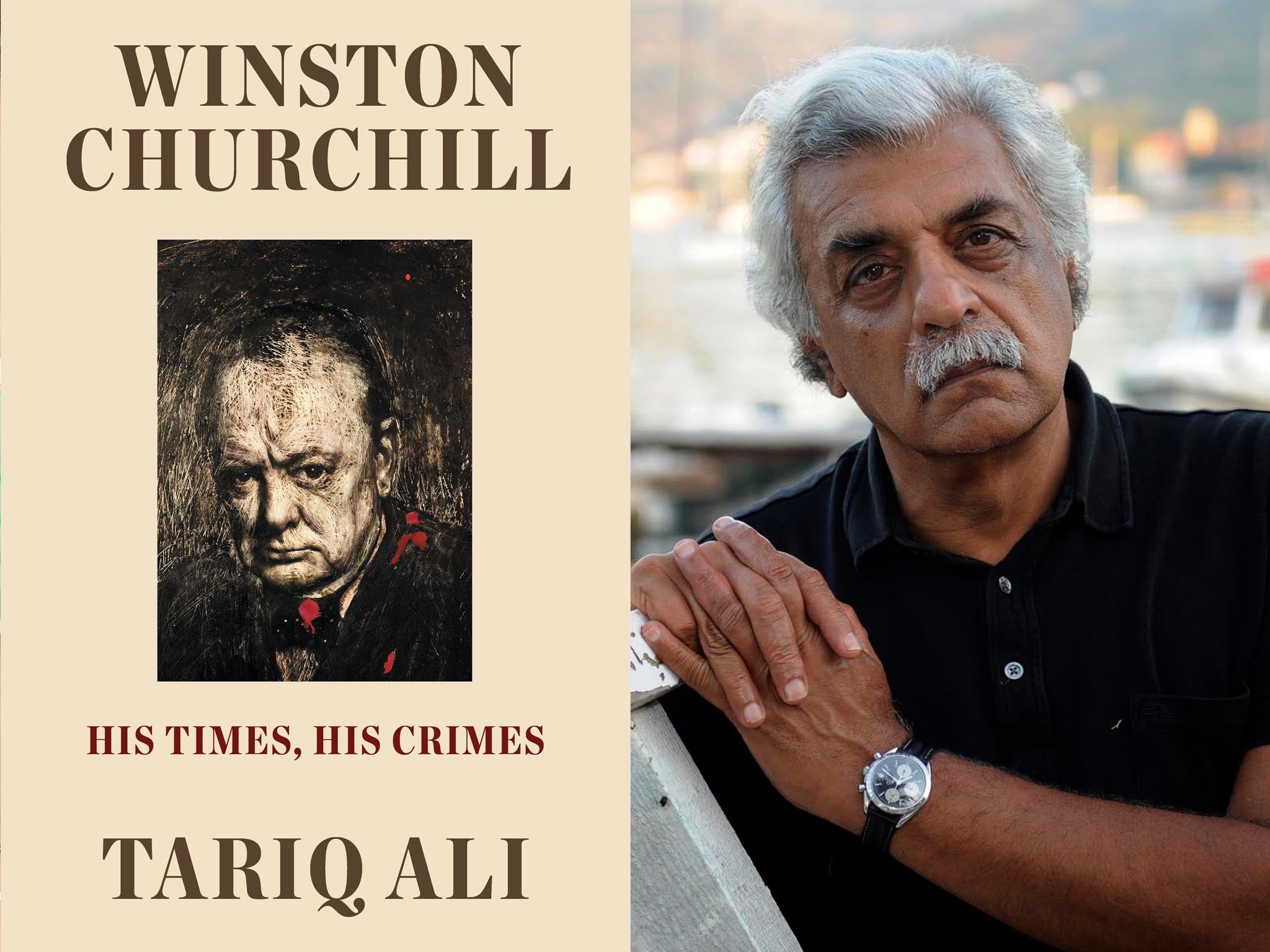

Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes by Tariq Ali ★★★☆☆

According to Tariq Ali, Winston Churchill is “a burnished icon whose cult has long been out of control”. He believes that a modern “deification” of the man who led Britain during the Second World War began with Margaret Thatcher’s glorification of Churchillian rhetoric in the post-Falklands war celebrations.

Ali, a member of the editorial committee of the New Left Review, offers a powerful corrective in Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes, shining a light on the nasty parts of the Churchill story that his supporters conveniently ignore. The book is an unreserved polemic against the man usually celebrated for standing up to Hitler.

Ali’s charge sheet includes Churchill’s offensive opinions about women’s rights; the way he cosied up to fascist leaders such as Mussolini and Franco; his complicity in the humiliating defeat at Gallipoli; his military miscalculations (in the late 1920s, he declared there was not the “slightest chance” of war with Japan in his lifetime); his complacency over the fall of Singapore in 1942; his mistakes over Cold War strategy; the way he revelled in the use of the atomic bomb; his “enthusiastic support” for the use of chemical weapons against Kurds and Arabs in the 1920s; and his ill treatment of British workers and Irish citizens. As if that’s not damning enough, Ali also details the abhorrent racism of a man who swore by “Anglo-Saxon superiority”.

As well as quoting Churchill railing against the “naked savages” of the Kikuyu in Kenya, Ali’s account also scrutinises his “systematic colonial war crimes” in Africa and against Bengalis. His salient points are occasionally let down by pejorative rather than analytical dissection. It is revealing to learn of Churchill’s zest for the brutality of the British army towards the Sudanese in 1898, but referring to Churchill’s “war orgasms” feels overcooked, while citing his portrayal in the television drama Peaky Blinders to back up allegations about Churchill’s love of “dirty tactics” seems flimsy.

One of Ali’s most damning sections deals with Churchill’s reaction to the arrival of the Windrush generations (Ali also makes clear the shameful response of Labour prime minister Clement Attlee), including a claim that “Churchill thoughtfully suggested that the Tory election slogan for the 1955 general election could be ‘Keep England White’”.

Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes is not a standard biography and is aimed at providing context. If you want a straightforwardly lickspittle account of Churchill, then Boris Johnson’s 2014 biography, commissioned by Churchill’s estate, will fill that gap. Johnson said that while he was growing up his father would often recite famous lines from Churchill’s wartime speeches. Johnson’s inspiration for how to be a leader were based on Churchill.

Ali’s counterview is that Churchill’s legacy is a corrosive one, and glorification of him is part of the reason, “like it or not, we are living in the twilight period of democracy”. For what it’s worth, I read that line on the day Johnson refused to resign despite becoming the first sitting prime minister to be punished for breaking the law.

‘Winston Churchill: His Times, His Crimes’ by Tariq Ali is published by Verso on 10 May

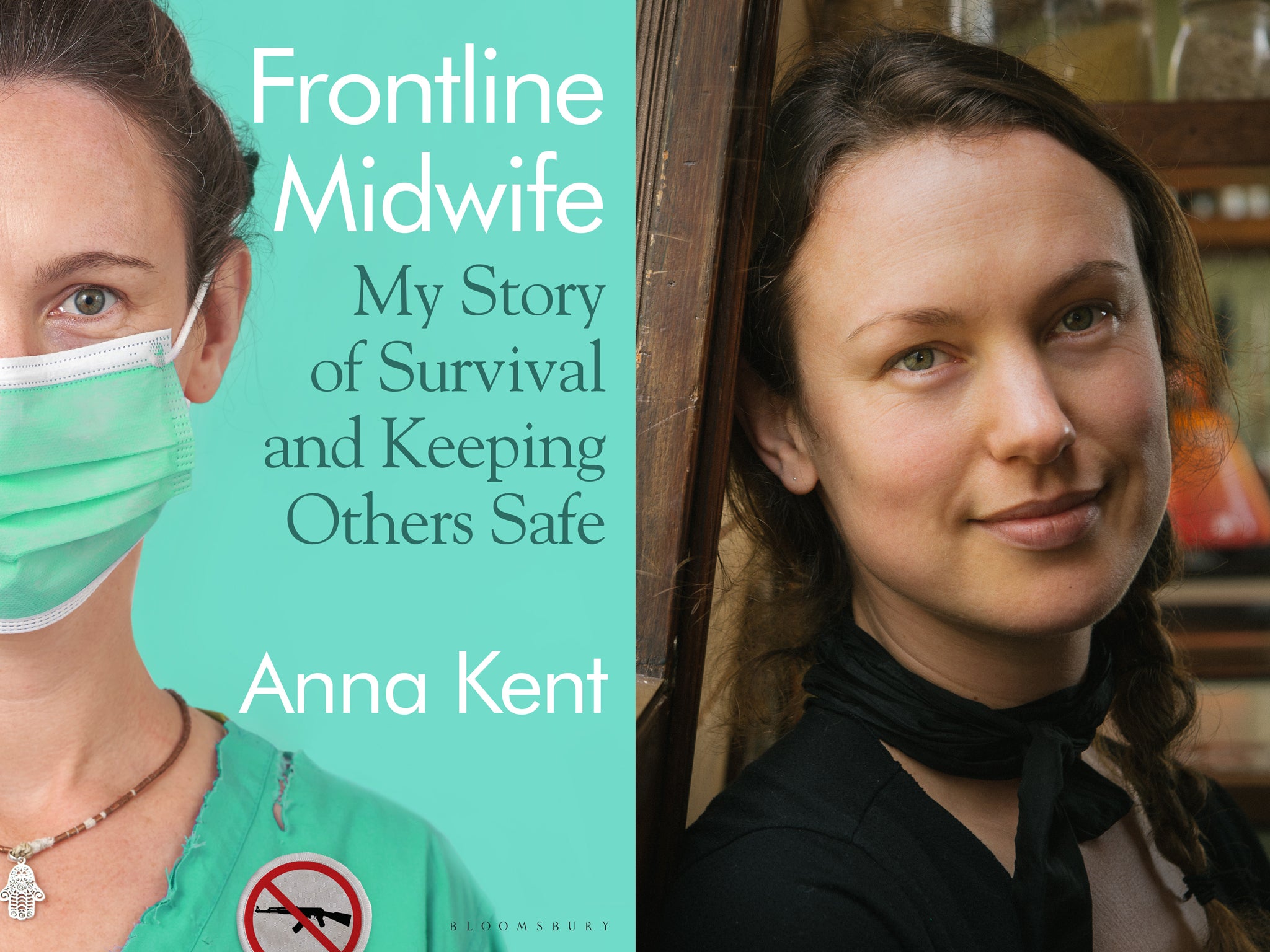

Frontline Midwife: My Story of Survival and Keeping Others Safe by Anna Kent ★★★★☆

South Sudan after the heavy rains of May sounds terrifying. The ground turns into a brownish-red quagmire and the snakes, scorpions and mosquitoes come out to play. “Scorpion avoidance was now part of the daily routine,” recalls Anna Kent, who was in her twenties at the time and working as a midwife for Medicins Sans Frontieres. “Going to the latrine at night had to be done in the dark, otherwise the headtorch attracted massive bluebottles that lived in the poo and would skydive into your face”.

Giant attacking flies was a picnic compared to most of Kent’s experiences delivering babies in a war zone and caring for deeply vulnerable women. Frontline Midwife: My Story of Survival and Keeping Others Safe, written with the help of author Julia Gregson, is a searingly honest account of Kent’s experiences in Africa, Haiti, Bangladesh and Nottingham.

This brutally powerful memoir is full of incidents and suffering that will stay in your head – I’d never heard of “the Burmese stick” or “destructive delivery” and will not soon forget them – and the stark, diary-style account somehow makes everything seem particularly real. “I feel broken into pieces,” admits Kent – and who wouldn’t after dealing with horrific situations involving female genital mutilation, the rape of “stateless” women, illness, disease and death?

The peril of death is very real in the book. In South Sudan, more young women die in childbirth than go to secondary school. Things are just as tough in Bangladesh, where Kent treated Rohingya refugees from Myanmar in a camp in Kutupalong that was a vast stinking landscape of decrepit shacks, made from mud. The flow of anecdotes brings home why watching such suffering gradually began to poison her mind.

Despite all the misery, Kent has the capacity to make light of her own disasters. In one potent account of a desperate drive home to her parents after splitting from a boyfriend, she recalls what happened as he began listening to Gnarls Barkley sing “Crazy” just as her bowels started to rumble. She pulled over to relieve herself in a bush rather than having to “s*** in a hire car”. “I knew I’d hit rock bottom,” she writes.

Although it’s a stark read, Frontline Midwife is totally absorbing because Kent holds nothing back, including about her own tragic experiences of miscarriage and loss.

The book offers a window into a world that few of us could honestly face.

‘Frontline Midwife: My Story of Survival and Keeping Others Safe’ by Anna Kent is published by Bloomsbury on 12 May, £18.99

The World in 2050: How to Think About the Future by Hamish McRae ★★★☆☆

If you’re 29 now, you’ll be my age when the mid-point of the 21st century rolls around. What on earth will the world be like then? In The World in 2050, Hamish McRae, who writes about economics for The Independent, takes some educated guesses. In passages written before the invasion of Ukraine, he makes salient points about the bleak future for Russia and its already “diminished status”. He predicts that Russia has already overplayed its hand “and may suffer some sort of convulsion that damages both itself and its neighbours”. The author foresees a much rosier economic future for America.

McRae, who fears that global cooperation may remain a pipedream, guides the reader through the looming changes in terms of artificial intelligence, technology, climate, finance and population coming our way.

The book is surprisingly optimistic about the UK’s future, incidentally, foreseeing a path where migrants from the English-speaking world allied to growth in the goods and services industry, “will lead the UK to become Europe’s biggest economy”. As we wilt under the latest cost of living crisis, this all seems a distant, unlikely expectation. It’s not the despair, Hamish, we can take the despair. It’s the hope we can’t stand.

‘The World in 2050: How to Think About the Future’ by Hamish McRae is published by Bloomsbury on 12 May, £25

Spring Tides: A Story from a Small Island by Fiona Gell ★★★★☆

Dr Fiona Gell, who has a PhD in seagrass ecology, returned to her childhood home of Ramsey Bay on the Isle of Man after 12 years away studying marine life. She brings all her dedication as a conservationist to Spring Tides, a passionate, moving account of the transformative power of the sea and the importance of protecting it for the future generations.

Although marine life is not a subject I’d usually rush to read, I enjoyed her descriptions of sea life, including the “strangely beautiful” meaty-looking cubes of red that make up herrings’ hearts. The photographs in the book are intriguing and it was eye-opening to learn how scallop fishers are now helping conservationists by using specially designed digital measuring boards to collect data for universities.

Gell weaves her own family history and personal life into the memoir, including a moving account of suffering a miscarriage and how having to conduct autopsy work on a stranded minke whale a week after her own tragic loss exposed the rawness of her emotions.

Her account of the way oceans and seas are being destroyed is worrying – she details the problems caused by the fact that the ocean is 30 per cent more acidic now than at the start of the Industrial Revolution – but her epilogue is full of optimism. Gill believes that marine conservation, especially restoration and rewilding, is now being embraced around the British Isles and around the globe. “We can harness the superpowers of the oceans, we can restore our seas, we can change the world,” she concludes… a sentiment to make any of us as happy as a clam.

‘Spring Tides: A Story from a Small Island’ by Fiona Gell is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on 26 May, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments