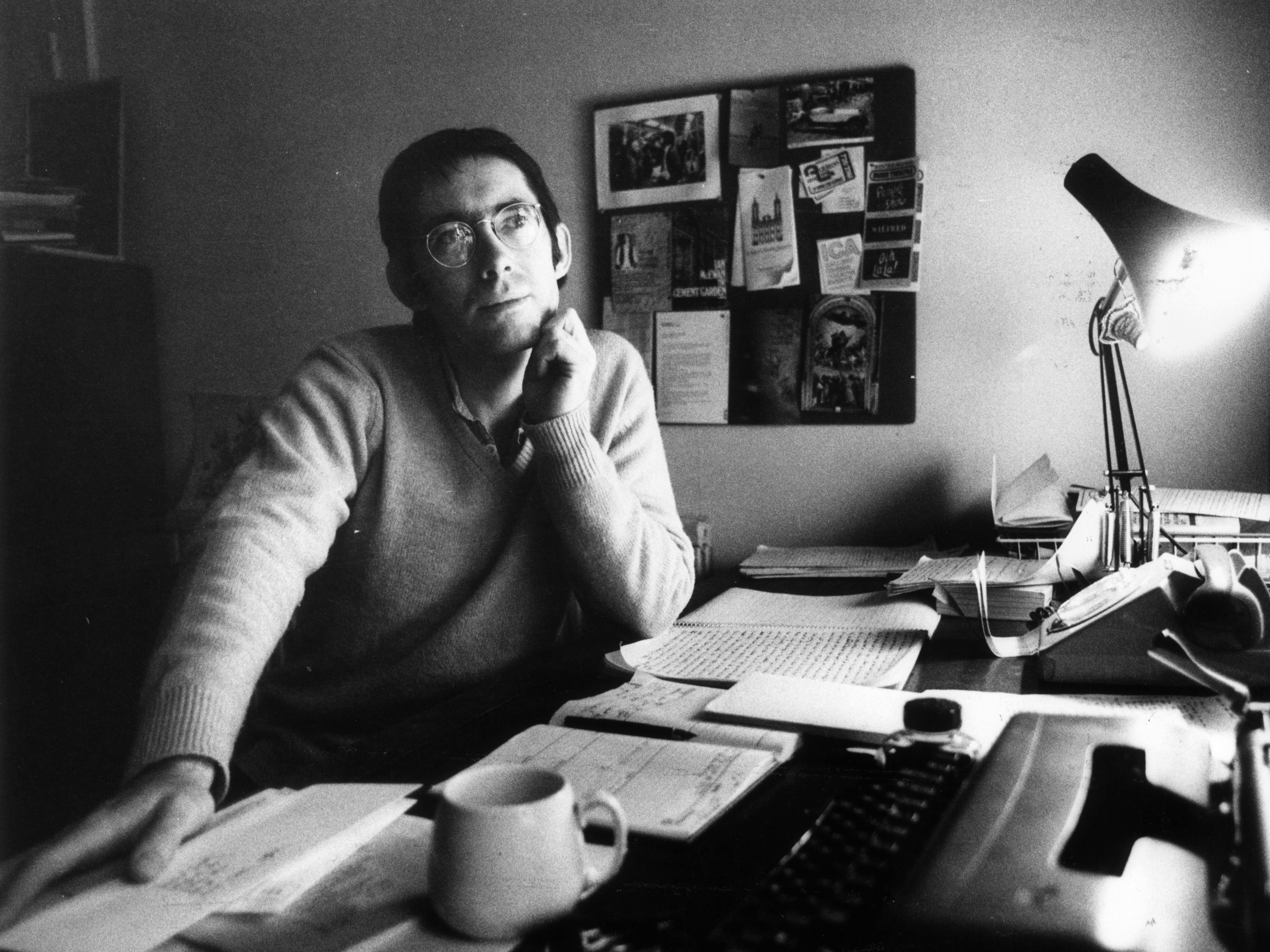

Book of a lifetime: The Cement Garden by Ian McEwan

From The Independent archive: Kitty Aldridge has a transformative experience while reading this shockingly transgressive masterclass in clarity and precision

In 1975 Ian McEwan was famous at our school because his short story collection, First Love, Last Rites, was sensationally banned by our doddering headmistress, Miss Gems. After examining a stray copy, Miss Gems set about full-scale censorship to protect us from what she declared was a shocking, dirty book. Copies were confiscated and detentions were issued to those of us who admitted to having read it. We found it hilarious. As a result of the ban, everyone saved up to buy a copy.

These days it is my original 1978 hardback of The Cement Garden that I treasure. At school, I was obliged to keep it hidden under the mattress, along with McEwan’s second collection of stories, fittingly entitled In Between the Sheets. We had admired the daring short stories, but for me, The Cement Garden had a deeper transformative effect.

As a youngster, I had the misplaced idea that literary works were required to be set either in Britain’s most undulatingly bucolic counties or in exotic places: Catalonia, Congo, Havana. I knew Orwell, Conrad and Hemingway were well travelled; McEwan it seemed, by contrast, had tossed aside his passport in favour of the cul-de-sac UK in all its shabby suburban reality. The fact that the novel is set in an ordinary house on a decrepit street was as shockingly transgressive to me as the incest that takes place in the story.

From the first page, McEwan’s calm, exquisite sentences lead you into the secret and strange world of the post-war middle-class family, with its unique clash of make-do-and-mend and sexual revolution. Devastating information is relayed in short, cool-headed paragraphs, increasing the charged atmosphere of disorder and horror. To avoid being taken into care, the four children – suddenly orphaned – bury their mother in cement in the basement, after which they attempt to continue a normal life, with the eldest, brisk, manipulative Julie, in charge.

The novel is a masterclass in clarity and precision; the imperturbable authority of the author is felt but not heard. The voice is all teenage Jack’s: callow, baffled, self-pitying. I held on to my hardback copy as I grew up and left home, through addresses, jobs and relationships, as if the physical book itself now had talismanic properties. I no longer keep it under my mattress, but it is in my heart for all time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments