Books of the month: From Mothers, Fathers, and Others to The Oracle of the Night

Martin Chilton reviews four of December’s biggest releases for our monthly column

One of the month’s top audiobooks is certain to be Amanda Gorman narrating her own debut poetry collection Call Us What We Carry (Chatto & Windus). Gorman, the 23-year-old whose reading at Joe Biden’s presidential inauguration proved such a moving moment in early 2021, says the 80-page collection explores themes of memory and loss. “I wanted to pen a reckoning with the communal grief wrought by the pandemic,” she commented. “It’s been the hardest thing I’ve ever written.”

Janine di Giovanni, a former winner of the Courage in Journalism prize, is a shining example of the dwindling band of investigative reporters. The Vanishing: The Twilight of Christianity in the Middle East (Bloomsbury) looks at the plight of Christian communities in the Middle East. As well as reporting on small hardy religious communities and their ancient rituals, Di Giovanni also details the horrendous persecution they face. She recounts the tale of the Isis terrorist groups in Syria and Iraq who sell Christian women into sex slavery, sometimes using live video markets. “I could not believe that a slave market was taking place in the 21st century,” writes Di Giovanni, who worked with women’s groups trying to help sex-trafficked women. “It seemed grotesque, medieval, savage. The women were young – many of them girls really, in their teens – who were in shock, tears running down their faces, powerless. The fighters were older, bearded and armed.”

You might not start 2022 in an optimistic frame of mind if you read Chris Begley’s The Next Apocalypse: The Art & Science of Survival (Basic Books). Begley, a professor of anthropology, is a survival coach. He looks at what happened with previous doomed civilisations – including the Maya, the Roman Empire, and Native American societies – to evaluate what can help us in a future collapse. “We should not understate the severity of the impact of climate change that we have been ignoring for 50 years or more,” writes Begley. “The next apocalypse will be brutal, tragic, and costly.”

If all this sounds too grim and gruesome for the festive period, then there is no shortage of positive self-help books, a market estimated to be worth nearly £10bn a year. Among December’s offerings is Rise and Shine: How to Transform Your Life, Morning by Morning by psychologist Kate Oliver and yoga teacher Toby Oliver. The two authors explain their S.H.I.N.E. breakfast-time regime (S is for silence; H is for happiness; I is for intention; N is for nourishment; E is for exercise). My advised morning routine, which you can have for free, is to eat plenty of bran and avoid hearing interviews with politicians.

I enjoyed the sour wisdom in John Koenig’s The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows (Simon & Schuster), which evolved from the author’s hit blog. It is a quirky book full of imaginative new terms that define the maladies of modern life. I guess we all need a bit of “mogging folly” – which Koenig describes as “the act of deliberately squandering your time, lazing about as if none of this is worth a damn, letting precious hours spool away slowly like the string of a runaway kite”.

December is a quiet month for new fiction. Among the new novels out this month are Lori Ann Stephens’s Blue Running (Moonflower Books), a taut thriller set in a post-secessionist Texas, where open-carry gun ownership is mandatory. Is it dystopian or merely predictive? Meanwhile, RV Raman’s A Will to Kill (Pushkin Vertigo) is the first in a new crime series, set in India, featuring investigator Harith Athreya. The book is influenced by Agatha Christie and although the plot is reasonably twisty, the writing style was a little too perfunctory to really grip me.

For prog-rock fans, a welcome Christmas present would be Emerson, Lake & Palmer (Rocket 88 Books), the new official history of the band, in which Keith Emerson, Greg Lake and Carl Palmer tell their own story. The book includes rare and unseen photography. There is also a new version of David Katz’s People Funny Boy: The Genius of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry (White Rabbit), a thoroughly engrossing study of the magnificent Jamaican record producer and singer who died in August.

Finally, it will be harder to find a more niche book this Christmas period than Jordan Osserman’s Circumcision on the Couch: The Cultural, Psychological, and Gendered Dimensions of the World’s Oldest Surgery (Bloomsbury Academic), which promised to bring a “feminist Lacanian framework” to the history of circumcision. The book is hardly a snip, though, at £90.

Essays from Siri Hustvedt, philosophy from Alan Watts, a photographic history of Black Ivy fashion and Professor Sidarta Ribeiro’s study of dreams are reviewed in full below.

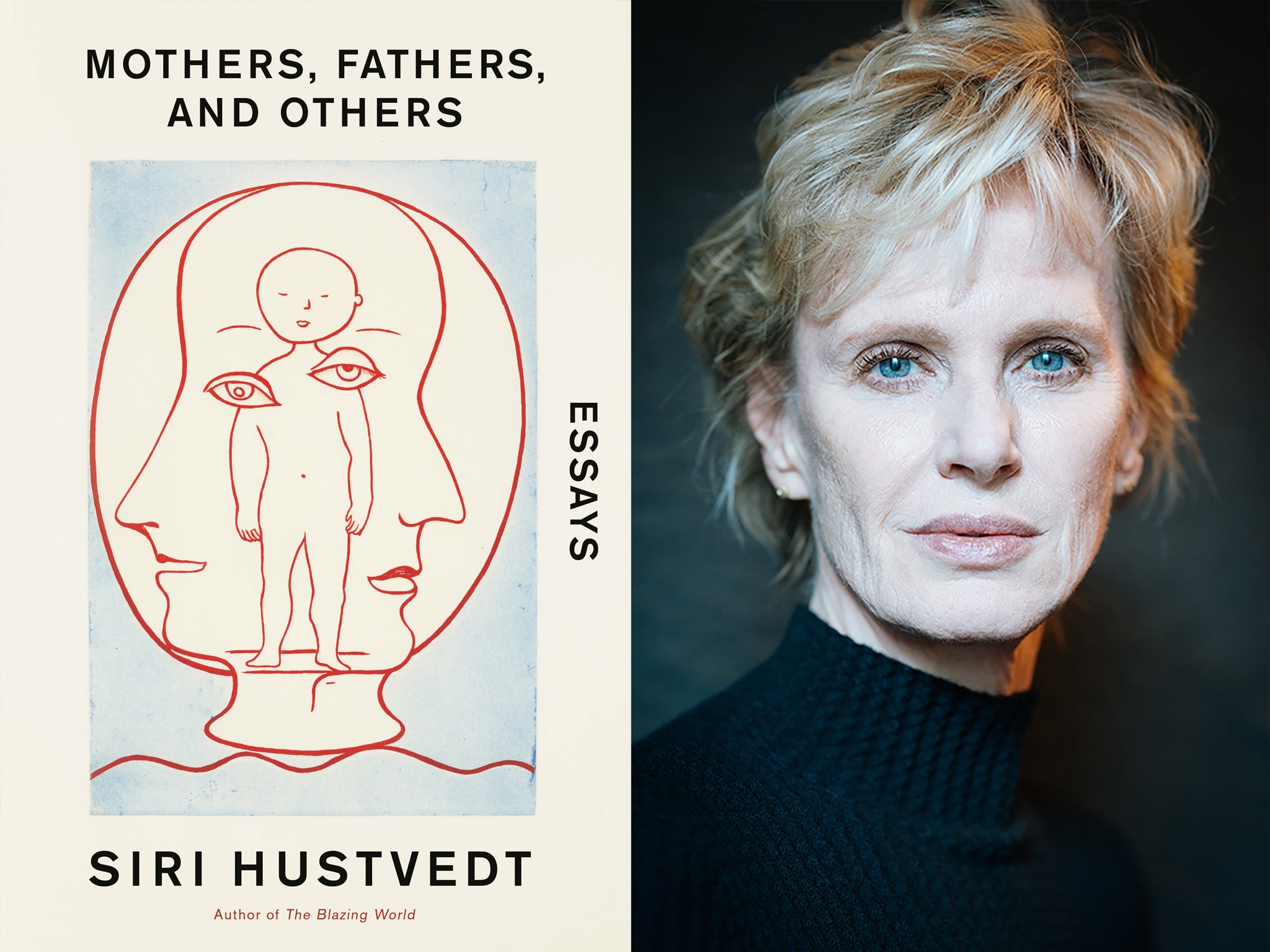

Mothers, Fathers, and Others: New Essays by Siri Hustvedt ★★★★☆

American novelist and feminist philosopher Siri Hustvedt is a wonderful essayist, equally at ease discussing the thoughts of Plato or the lyrics of Tom Waits. Her new collection, Mothers, Fathers, and Others: New Essays by Siri Hustvedt, replete with personal history and recollection, and sparkles with small descriptive gems. She is especially vivid about her own family history, recalling her father Lloyd, who had survived the Great Depression on a farm and then the horrors of the Battle of Luzon in the Philippines during the Second World War. “His face was a map of unhappiness,” she notes.

Hustvedt’s moving 2020 essay “A Walk with My Mother” recounts her relationship with her mum Ester and the wisdom her parent imparted late in life when the elderly Norwegian was suffering from congestive heart failure and gout, something that had “turned her thin legs into gigantic swollen logs”. Ester talks to Hustvedt about grief, recalling how the death of her own mother was “strange to lose a person who only wanted the best for you”. She also reminds her daughter that “of course, one loves one’s children, but it is just as important to respect them”.

The essays deal with an eclectic range of subjects, including the anti-intellectualism of Donald Trump, the difficulties faced by translators, the strengths of Jane Austen’s Persuasion and the pleasures of books in a lockdown. “The book is a geography where complete freedom remains possible,” she states in “Reading During the Plague”. She spent lockdown in New York, where she notes drolly that, “just as they did during the yellow fever epidemic of 1795, the cholera epidemic of 1832, and the flu pandemic of 1918, moneyed New Yorkers have fled town for their country houses to wait out the scourge, leaving behind the crowded and vulnerable poor who cannot afford ‘social distancing’.”

In the book, Hustvedt gives frequent mentions to the rise of misogyny, and she is sardonic about the “inappropriately angry men” she has come across. They include the sweaty college professor who “spat venom in my direction”, and the band of bearded, pipe-smoking philosophy academics at Columbia University who made her feel like a “polluting invader” just because she attended a seminar in their department out of simple curiosity. Perhaps it’s an age thing, but she ignited a spark of recognition in me by recalling the number of times as a child she heard adult men make the same dismal joke about women: “Can’t live with ‘em. Can’t live without ‘em”.

She is less sanguine about the number of times she has been denigrated in her career by virtue of being married to writer Paul Auster. Numerous members of the public (and some journalists), have suggested to her face that her husband must have written her best work. In response, she mocks the people who “foist their own your-husband-is-your-mentor fantasies onto me”.

In one aside, about Kate Manne’s book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, Hustvedt notes, “Manne does not tell many personal stories in her book but, in a footnote, she reveals that as a schoolgirl she was strangled by a boy who came in second in a spelling bee she had won. The rage starts early.”

The hardest read of the 20 essays is the final one, “Scapegoats”, about the horrific murder and torture of 16-year-old Sylvie Marie Likens by a dozen or so people in Indianapolis in the 1960s. She does a good job of explaining why she finds the case so fascinating and terrifying. “I do not think it is as abstract or unusual as is comforting to believe”, she says, as part of a shrewd analysis of mob behaviour and how easily group violence is encouraged. “The crowd gathers at a rally or it forms online. It bellows with one voice. It had its reasons. It is rife with pious feelings and honourable proclamations, and then it turns on its victim.”

Mothers, Fathers, and Others: New Essays by Siri Hustvedt is published by Sceptre on 2 December, £20

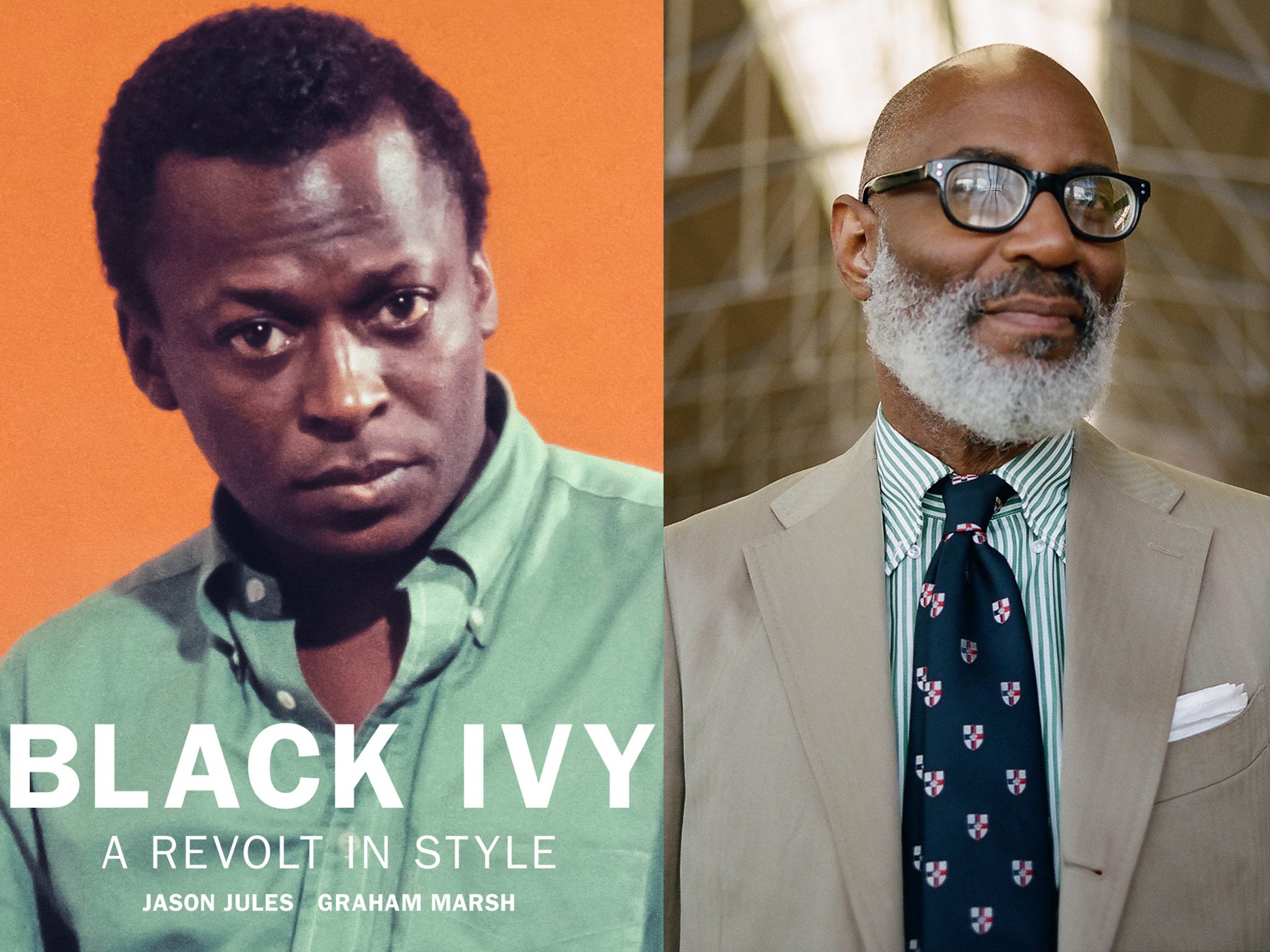

Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style by Jason Jules and Graham Marsh ★★★★☆

“You’ve got to have style in whatever you do,” said jazz trumpeter Miles Davis, whose photograph adorns the cover of Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style, a book that looks at how a generation of black men took the “Ivy Look” and made it edgy and cool in a way that still influences menswear. The Black Ivy style of the 1950s and 1960s was “a kind of sartorial power grab,” writes Jason Jules, the writer and editor of the book (Graham Marsh was responsible for art direction and design).

The book is a magnificent piece of photographic social history – broken up into chapters about the Black Ivy look in literature, arts, music, film, politics, sports, advertising, civil rights demonstrations and marches and in urban environments. Of course, Davis was, according to Marsh, “the essence of Ivy hipness,” looking extremely slick in his immaculately tailored suits.

Even for a fashion disaster like me, the appeal of the wonderful clothes in the book is palpable, and although I admired the featured attire of jazz stars such as Grant Green, Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane, I got a serious case of cardigan-envy at the one worn by Blue Note Records vibes star Bobby Hutcherson – a beautiful crew neck number, with the Alpine style brushed wool and metallic buttons popular in the Sixties.

The book is full of superb photographs – more than 50 of the era’s best camera masters are featured – including one publicising Sidney Poitier in the 1967 film To Sir, with Love, which is set in London’s East End. The Oscar-winning actor looks way too cool to be a teacher, in his Ivy jacket, complete with patch top pocket and repp tie. Other visual highlights include Muhammad Ali in his Oxford button-down shirt and a wonderful John G Zimmerman photograph of Arthur Ashe travelling unrecognised on the New York subway the day after he won the US Open in 1968. The tennis star looks a picture of elegance in his fine knit short-sleeve V-neck jersey and beef-roll loafers.

The book is a revealing study of the role clothing played during a period of upheaval and social change. Clothes were, say the authors, “symbolic armour in the battle for equality”. The decline in the popularity of the Black Ivy style began with the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King. Needless to say, there is a telling picture of King and his fellow civil rights activists dressed in tie clips, capped brogues, collar pins and smart suits. King, said Jules, was “taking the idea of power dressing to another level”.

Black Ivy is a truly absorbing book of photography.

Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style by Jason Jules and Graham Marsh is published by Reel Art Press, 7 December, £39.95

There Is Never Anything but the Present & Other Inspiring Words of Wisdom by Alan Watts ★★★☆☆

Alan Watts, the sage who popularised Zen Buddhism in America and influenced the beat and hippie generations, was born in Chislehurst, Kent, and educated at King’s School, Canterbury. He left for America before the outbreak of the Second World War. He ended his days living on a houseboat in Sausalito.

There Is Never Anything but the Present & Other Inspiring Words of Wisdom, a book with a handsome design by Pei Loi Koay, captures the essence of his beliefs in more than 100 one-per-page nifty aphorisms, many expressing his idea that Zen was, above all, the liberation of the mind from conventional thought. And be honest: who doesn’t occasionally hunger for a few little inspiring words of wisdom? If your taste is for some morsels of eastern philosophy, then the writings of Alan Watts will fill you up like Christmas party snacks.

The nuggets, collected from an array of his works including Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown: A Mountain Journal, Does It Matter?Essays on Man’s Relation to Materiality and his memoir In My Own Way, are meant to prompt introspective reflections. Among the ones I particularly liked were:

“If happiness always depends on something expected in the future, we are chasing a will-o’-the-wisp that ever eludes our grasp, until the future, and ourselves, vanish.”

“To be afraid of life is to be afraid of yourself.”

“There is a point where thinking – like boiling an egg – must come to a stop.”

However, some of his sayings are simply banal and, as the old folk of Holborn used to say, a “statement of the bleedin’ obvious”, as in “a chest of gold coins or a fat wallet of bills is of no use whatsoever to a wrecked sailor alone on a raft”.

For Watts, the road to Zen Buddhism began in reading the novels of Sax Rohmer, the creator of detective Dr Fu Manchu, the stereotypical Chinese character who was hugely popular in a bygone age. Watts is certainly a bygone thinker, but this book is a reminder of why he was such a cult figure in the 1960s before his death in 1973 at the age of 58. His bitesize brain treats would have made him a Twitter sensation in our time.

There Is Never Anything but the Present & Other Inspiring Words of Wisdom by Alan Watts is published by Rider on 9 December, £9.99

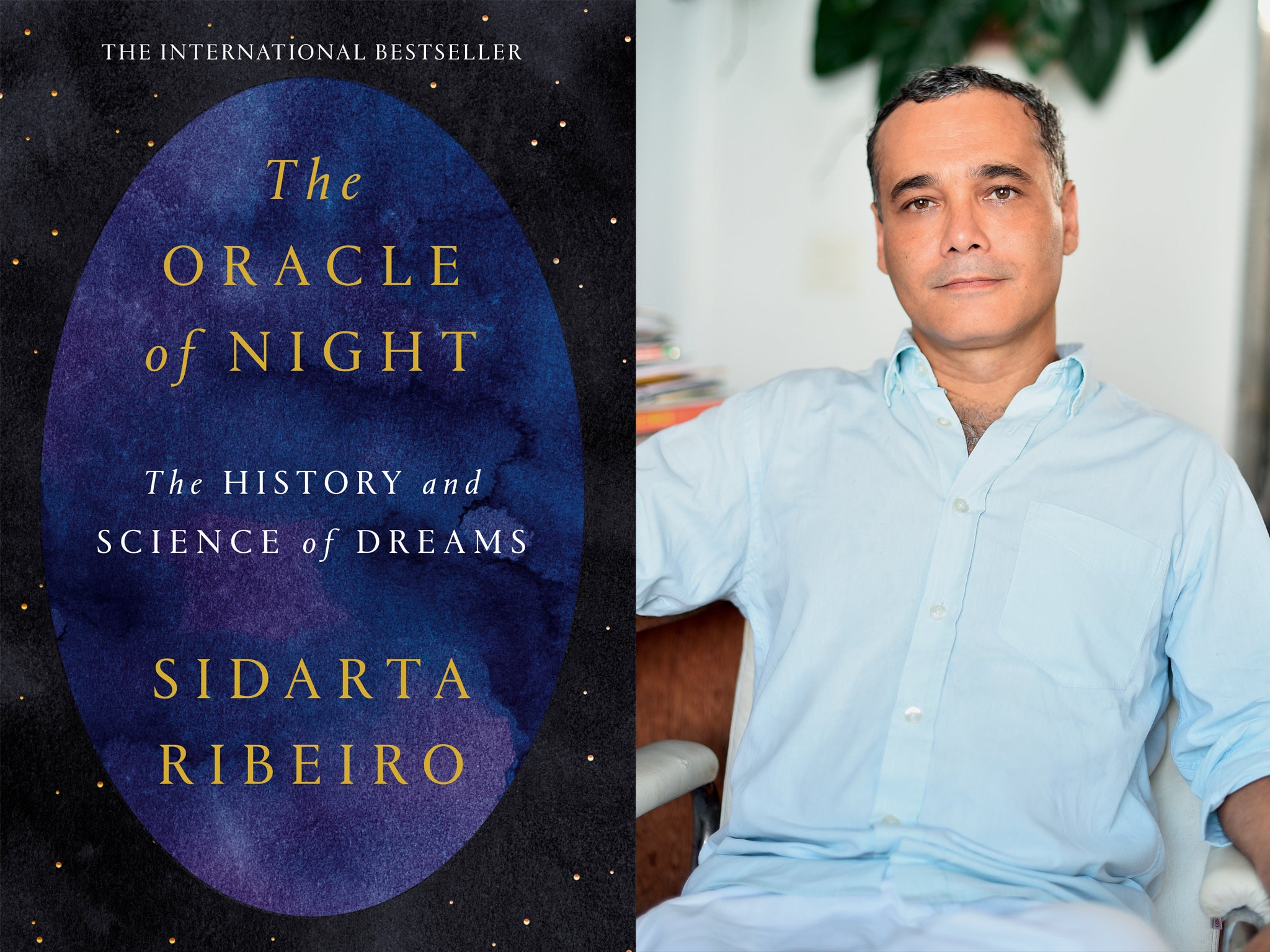

The Oracle of the Night: The History and Science of Dreams by Sidarta Ribeiro ★★★☆☆

We all dream for most of the night. The good news, for those of us who fill our brains with rubbish during the day, is that it is now understood that dreams provide an efficient “cleaning out of molecular trash” (such as beta-amyloids) that are accumulated by the brain during our waking hours. “Only in the last five years has it become clear that one of the most important functions of sleep is the detoxing of the brain,” writes Sidarta Ribeiro, a professor of neuroscience, in The Oracle of the Night: The History and Science of Dreams.

Ribeiro, the founder of Brazil’s prestigious Brain Institute, has written a detailed, complex guide to the history, science, philosophy and psychology of dreams. Although it’s a complicated read, the book, translated from Portuguese by Daniel Hanh, is accessible and goes off at numerous interesting tangents. Dreams – which are defined as “a simulacrum of reality constructed out of fragments of memories” – tend to come in three basic types: the nightmare, the pleasurable dream, and the dream of the (usually fruitless) pursuit of some goal.

The book, which includes diagrams, tables, graphs and illustrations, discusses whether dreams have an oracular function. Perhaps we ignore night visions at our peril, as Calpurnia’s premonitory dream about her husband Julius Caesar the night before his murder would suggest. Nightmares have staying power. The author cites a study showing that 270,000 Vietnam veterans are still suffering from PTSD sleep disorders more than half a century after the conflict.

It seems, moreover, that intelligence affects the content of dreams. “The brain that dreams is the same brain that lives through waking experience, and so the more complex the mental tissue, the more complex the dreams will be, too,” Ribeiro states.

Dreams aren’t all bad, of course, and can contribute hugely to human creativity. Just ask Paul McCartney, whose sublime melody for “Yesterday” came to him in a reverie. The Oracle of Night takes you down lots of unexpected paths, as it covers subjects as diverse as Freud’s dream theories, the beliefs of Tibetan monks, the benefits of power-nap dreaming and dream patterns in animals.

Most of us are puzzled by our strange dreams. There is much new work going on in the fields of decoding dreams and investigating electrical brain waves, all of which, Ribeiro says, suggests that “an age of dream transparency might perhaps be approaching”. That dream-explaining App can’t be far away.

The Oracle of the Night: The History and Science of Dreams by Sidarta Ribeiro is published by Bantam Press on 30 December, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments