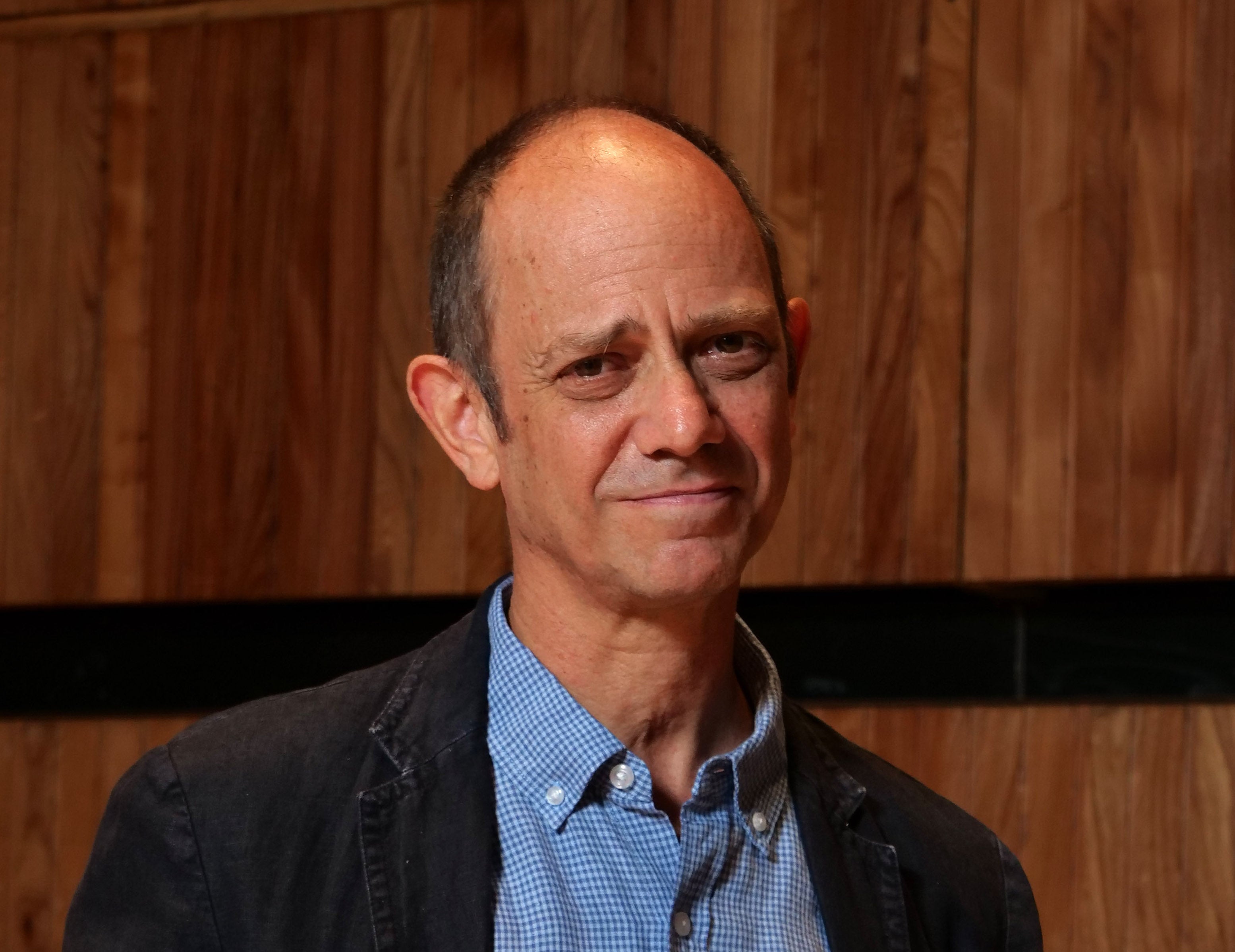

Booker winner Damon Galgut: ‘My family were not raging racists, but they were fairly comfortable with the set-up’

After two previous shortlist disappointments, the South African author has claimed victory with his mesmerising ninth novel ‘The Promise’. He talks to Martin Chilton about growing up in a racist and often dangerous country, his dark childhood, and the fleetingness of time

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

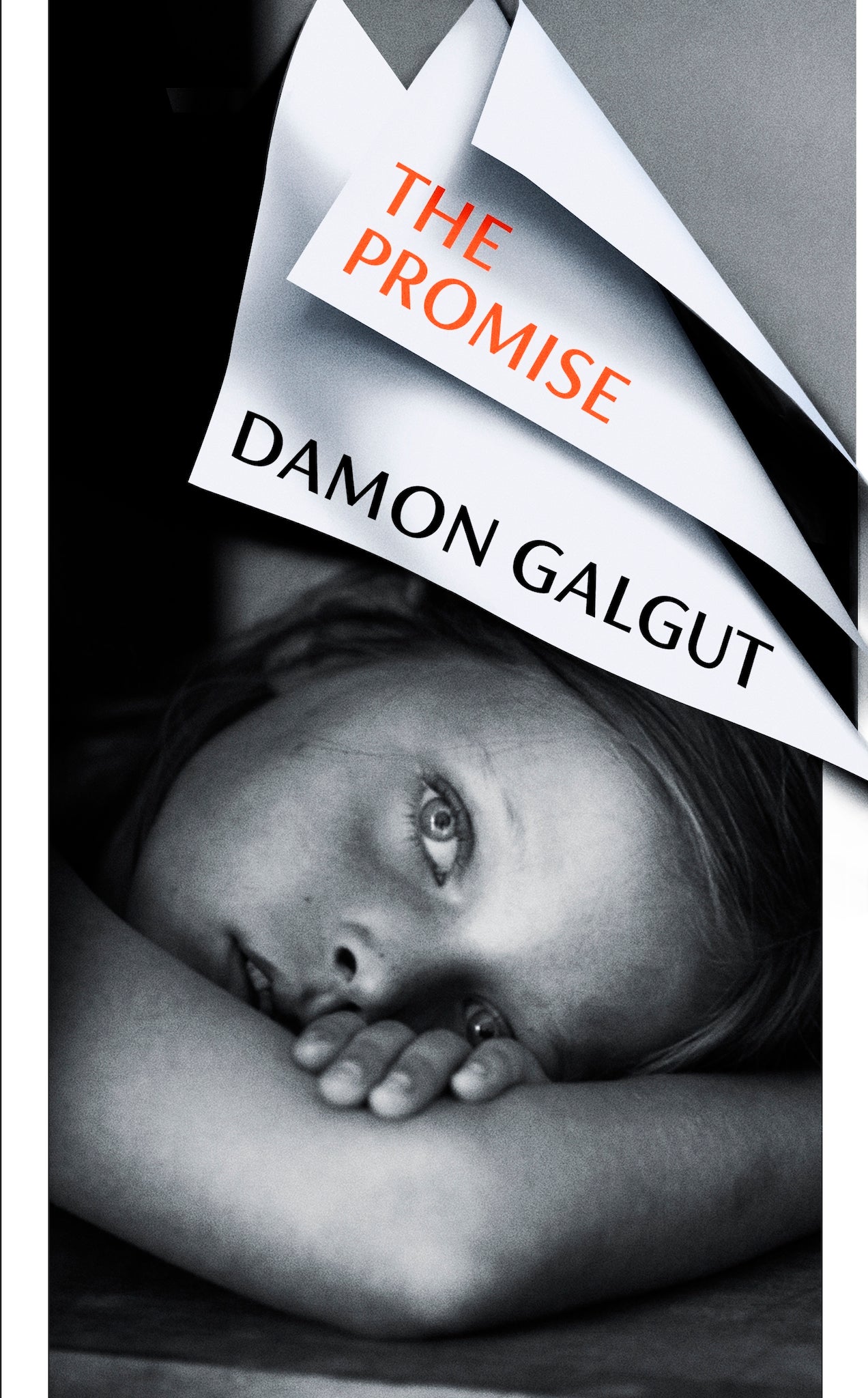

Your support makes all the difference.“I didn’t ever think I had a realistic chance of winning, because The Promise is just too odd a book,” says Damon Galgut. The author was, he admits, a bit “sandy-eyed” the morning after celebrating winning the Booker Prize for his magnificent ninth novel.

Two previous shortlist disappointments (The Good Doctor and In a Strange Room in 2003 and 2010 respectively) left him feeling “like one of those cartoon animals that has run off the edge of a cliff and you are still in motion” because of the way that weeks of a “full blast of attention” suddenly ended. Now he is firmly in the permanent spotlight, having taken his own advice, to “just recover, move on and write another book”. The third time worked a charm with The Promise, his mesmerising drama about a South African family whose deathbed promise to their black housekeeper – ownership of her property – is not kept.

The 57-year-old is wearing the sort of comfortable green jumper befitting an autumn day when we meet at the Groucho Club in Soho. He knows London from the 1980s, when he did odd jobs to fund travel around Europe, America and South America. “I worked in an antique shop in Islington, I worked for a catering company and I was a nude model for life drawing classes,” he recalls. “I was in high demand because I could sit very still for long periods. The pay was about £6 an hour, but it was easy work and under the counter. Somewhere in this city are hopefully badly executed drawings of me naked. Maybe they are very accurate, but I have never seen the results.”

It has been “many years” since Galgut has been out of South Africa. Although lockdown meant “little disruption” to his solitary life as a writer, aspects of the restrictions were baffling. “There was no exercise, no walks on mountains or in the park; you could go down to your local store and that was it,” he explains. “We had bizarre rules that no one understood. For example, you weren’t allowed to buy open-toed sandals!”

One of the most stressful factors was the collapse of his Cape Town restaurant, a business called Masala Dosa, serving South Indian cuisine, which he’d taken over from a friend. “I don’t know what I was thinking. Restaurants are notoriously unpredictable businesses. It just became this black hole sucking down money, time and effort. The food was good but it was a disaster, and it became a full-scale disaster when Covid hit. The experience did have the virtue of introducing me to real life as it is lived by most people. I had been in a bubble and this was like falling face first on the pavement.” So not the place to invest your £50,000 Booker windfall? “Don’t worry, I will never ever go near a restaurant again,” he says.

The restaurant was in an area of Cape Town that “went from being really popular and touristy to being really dicey at night,” he says. In The Promise, set around four funerals over four decades, one of the main characters is killed during a carjacking in Pretoria. “It is no secret that South Africa is a violent, crime-ridden society… everyone who can afford it has security. Higher walls. Electric fences. Alarms. It is an unnatural way to live, but it is an absolutely realistic possibility that people will break into your home and kill you if you don’t protect yourself.”

Has he suffered violence? “I had people break into my house and steal some small items,” he says, adding, almost in passing, that he was mugged a few years ago. That must have been traumatic. “Yes, it was actually. I was walking down an ordinary street in town. Lots of people were around and three guys cornered me. There was a building site next to us and they picked up bricks and pushed me against the fence. You give them what they want, because it is not worth dying for. Theft in itself is oddly disturbing, even if you don’t lose anything significant. It is the fact that somebody, by force, takes something from you. It upsets your mind.”

One of the main characters in The Promise is Amor Swart. For a long time, the book took the working title Dark Love from her Afrikaans name. “I was trying to play with the idea of South Africa being a country you could only love in a dark kind of way,” says Galgut, who was born in Pretoria in 1963. He grew up during Apartheid, which he describes as a “pretty lunatic time”.

While studying drama at the University of Cape Town, he had his eyes opened to the truth about his homeland. “My family were not raging racists, but they were fairly comfortable with the set-up. My grandfather was a judge in Apartheid times. I remember having a very memorable argument with him at the dinner table. I told him about a student protest where police had beaten us and, bizarrely, stripped people naked. He said, ‘Nonsense, they don’t do that!’ Growing up in Apartheid was kind of crazy. I remember seeing a Ben Elton sketch on television of Margaret Thatcher going down an escalator and saying, ‘This escalator is going the wrong way.’ It felt a bit like that: people insisting that reality was the other way around.”

Amor, who wants to honour the disputed promise to family maid Salome, is hit by lightning as a six-year-old. “I like the slightly mysterious ambiguity about whether she is morally driven or maybe she is damaged and there could be things wrong with her,” says Galgut. Her accident happens at the same age Galgut was diagnosed with cancer. “I wasn’t trying to make any big statement,” he says. “Being ill made me introspective and with a sense of being a little apart. We all get shaped in some way. I was very quiet as a child and listened and observed more than participating. You need to be a bit of a spy by nature if you want to write. I was a dark and troubled child. I had a violent and abusive stepfather. So, childhood was a bit of a war zone. That sort of launched me into adulthood with a dark disposition, but I found ways to shed that as I got older.”

The adult Galgut comes across as a shrewd, friendly and sardonic man, one who talks about having “a strong sense of evolution” about his life. “I feel a lot lighter and more accepting of the world and people than I used to be. But on the other hand, if you ask me about South Africa, I can’t remember a time when I felt less hopeful.”

The first draft of The Promise was longer than the final 292-page version. Galgut always starts by letting his “unconscious spill out” and then “pares these ideas down to the bones” as he works “on the elegance of expression”. His next book will be a collection of short stories, all with the theme of people who are away from home, either travelling or displaced. “I don’t know why at this point in my writing career I still succumb to illusions, but for some reason I thought short stories would be easier than writing a novel. That’s nonsense. They are just as challenging – more so in some ways,” he says.

Before we part, we share old-man-conversation about bad backs, Pilates, yoga and a mutual love of old fountain pens. I tell him that what I loved most about The Promise was the way he captures the fleetingness of time. “I’m glad you say that, because time for me is the real subject of the book,” he says. “I feel more and more that life has this dual quality of being heavy and substantial in one way and, on the other hand, being like a dream, like smoke. You forget stuff that seemed important and you feel as if it is all kind of being erased as you go along. Shakespeare’s thing about life essentially being a dream feels very true.”

‘The Promise’ by Damon Galgut is published by Chatto & Windus (£16.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments