The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Fear and Loathing at 50: Was Hunter S Thompson a ‘Bad Art Friend’?

Half a century after ‘Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas’ was first published, Kevin E G Perry investigates what the gonzo journalist’s masterpiece owes to his collaborator, Oscar Zeta Acosta

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On Friday 19 March 1971, the journalist Hunter S Thompson and the lawyer Oscar Zeta Acosta were sitting in the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel – “in the patio section, of course” – drinking singapore slings and plotting the high-speed desert trip that would inspire Thompson’s most celebrated work, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Fifty years and seven months later, I’m sitting on that same patio with the filmmaker Phillip Rodriguez, who made an incisive documentary about Acosta’s wild life and times, The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo. Reading Thompson as a teenager made me want to write for a living, so my plan had been to mark the 50th anniversary of Fear and Loathing first appearing in Rolling Stone by having a few drinks and toasting the memory of these two icons of cultural rebellion. Rodriguez has other ideas. “We have to rethink a lot of our gods,” he tells me, a smile breaking through his short-cropped snowy beard but his eyes deadly serious. “We become conservative if we’re still trying to preserve the mythologies of our youth.” I almost spit out my singapore sling.

These days, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas exists most powerfully in the popular imagination thanks to Terry Gilliam’s 1998 film adaptation, which starred Johnny Depp as Thompson’s alter ego Raoul Duke and Benicio Del Toro as Duke’s attorney, Dr Gonzo. On any given Halloween you will still find plenty of Raoul Dukes roaming the streets, cigarette holders clamped between their teeth, and a fair few Dr Gonzos trailing in their wake. In the film, as in the book, Acosta’s alter ego is essentially a sidekick, portrayed as a drug-crazed lunatic “Samoan”. When Acosta first read Thompson’s story, he had no problem being cast as a drug-crazed lunatic but was incensed that his identity as a proud leader of the Chicano civil rights movement had been erased. On top of that, Acosta believed he deserved credit for the work itself, in which much of the dialogue is reproduced verbatim from recordings Thompson made during their adventures in Vegas. “My God! Hunter has stolen my soul!” he wrote to Alan Rinzler, the editor who ran Straight Arrow, Rolling Stone’s books division. “He has taken my best lines and has used me. He has wrung me dry for material.”

Acosta’s unhappiness at Thompson using his words without credit is reminiscent of the recent debate, sparked by Robert Kolker’s New York Times Magazine essay “Who Is the Bad Art Friend?”, about whether writers can use language lifted directly from other people’s lives without being considered plagiarists. As it happens, when Thompson and Acosta arrived at the Polo Lounge that day neither had any intention of writing a cult novel. They just needed somewhere secluded to talk. Thompson had come to LA at Acosta’s request to investigate the death of the Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar. The previous August, Salazar had covered the Chicano Moratorium March in which a coalition of Mexican-American groups protested the war in Vietnam. Later that day he ducked into the Silver Dollar bar and cafe in East Los Angeles for a beer and was sitting at the bar when he was struck in the head and killed by a teargas canister fired into the building by an LA County Sheriff’s deputy. As one of the very few prominent Mexican-American journalists of his time, and a vocal critic of LA law enforcement, many in the Chicano community thought he had been intentionally assassinated. “Oscar was outraged by the mysterious circumstances in which Salazar died,” says Rodriguez. “He believed it was a story worth national attention.”

With Salazar gone, and with local white journalists disinclined to question the narrative set out by the Sheriff’s Department, Acosta put in a call to Thompson, whom he’d been friends with since a chance meeting in Aspen in the summer of 1967. “He knew that Hunter had access to national media in a way that he did not, and in a way that no Mexican-Americans did,” explains Rodriguez.

Thompson spent a largely sleepless, Dexedrine-fuelled week in East LA researching the story and running afoul of the Sheriff’s Department, but found it difficult to get Acosta alone to discuss the case. He was surrounded at all times by militant members of the Brown Berets, the Chicano equivalent of the Black Panthers, whom Acosta frequently defended in court. Many of them were suspicious of allowing a gringo reporter into their midst, while for Thompson and Acosta there was also the fear, later proved accurate, that some members of this entourage were paid informants for law enforcement. That was why Thompson took Acosta across town to the Polo Lounge, and it was there he suggested they escape their pressure-cooker environment for a weekend in Vegas. Sports Illustrated had offered him $300, plus, crucially, accomodation and expenses, to cover the Mint 400 motorcycle race that Sunday. All he had to provide was a few hundred words of captions to run alongside a photo essay. Acosta agreed, and they went together to a rental agency on Sunset Boulevard to hire the car they felt they needed for their journey: a fireapple-red Chevrolet convertible.

Hunter had white privilege, and for people who have white privilege, particularly of that generation, it’s invisible to them,

The death of Salazar is never mentioned in Fear and Loathing, but it was the primary topic of conversation for the pair as they sped towards the Nevada desert that Saturday morning. They shared a desire to expose the brutality and corruption of LA law enforcement, with Thompson viewing the incident as an attack on his profession. “When the cops declare open season on journalists,” he later wrote, “When they feel free to declare any scene of ‘unlawful protest’ a free fire zone, that will be a very ugly day – and not just for journalists.” Acosta, on the other hand, understood what had happened to Salazar as an act of racial violence against an indigenous population that had existed in California since long before the arrival of white settlers. Rodriguez believes this tension between the two men should inform how we read Fear and Loathing today. “Hunter had white privilege, and for people who have white privilege, particularly of that generation, it’s invisible to them,” he argues. “Their relationship is very germane to what’s happening in America today. What’s alive and what matters about Fear and Loathing, and Oscar and Hunter, is that negotiation between a coloniser and someone that’s fighting colonialism. That’s with us right now through Black Lives Matter et al.”

Having thrashed out the details of the Salazar case during their 300-mile road trip, Thompson and Acosta arrived in Vegas ready to let off some steam. They cruised the Strip, stopping at the Desert Inn where Hollywood star Debbie Reynolds was performing to a sold-out crowd, before drinking and gambling at the Circus Circus casino. The next day Thompson went out to watch the start of the motorcycle race, and in the afternoon drove Acosta to the airport so he could fly back to LA in time for a Monday court date. It was only later that Thompson realised Acosta had left behind his trusty attaché case, which contained a Colt .357 Magnum, a box of bullets, and a sizeable bag of cannabis.

Paranoia and exhaustion began to set in as Thompson wandered the casino floors alone that night. It wasn’t just that Nevada had the harshest anti-drug penalties in the country, there was also the matter of the gargantuan room service bill he and Acosta had run up, which he had no way to pay. He knew he would soon have to deliver his piece about Salazar, and on top of that he had signed a contract with Random House to write a book on the loose topic of the “Death of the American Dream” that had yet to take coherent shape. As he watched the gamblers handing over fistfuls of their hard-earned cash in the belief that one lucky streak could catapult them to a life of wealth and luxury, he realised he was looking at a twisted satire of social mobility. “Who are these people, these faces? Where do they come from?” he wrote. “They look like caricatures of used car dealers from Dallas, and sweet Jesus, there were a hell of a lot of them at 4:30 on a Sunday morning, still humping the American dream, that vision of the big winner somehow emerging from the last minute pre-dawn chaos of a stale Vegas casino.”

When morning came, Thompson fled his hotel and drove back to California. He checked into a motel in Pasadena and spent the next five days writing an epic 19,200-word piece about the death of Salazar and its ramifications for the Chicano movement. It was published under the headline “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan” that April in Rolling Stone, the longest piece the magazine had ever run. “I think Hunter did an outstanding and very fair-minded job,” says Rodriguez, who did his own investigations into the case for his 2014 documentary Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle. “To me, it’s one of the finest pieces that Hunter ever produced. His conclusion was much more sober than we might anticipate. Hunter did not find evidence of intentionality on the part of the sheriff’s deputy, but ultimately Salazar did die as a result of police violence. There was no way for them to know he was in that bar, but it was still reckless, it was still abusive, and it was still an expression of white violence against beleaguered minorities.”

They spent the rest of the day driving around Vegas, asking for directions to the American Dream. Most people assumed they were joking

At the same time he was writing his Salazar piece, Thompson began typing up the pages of notes he’d taken in Vegas and shaping them into a hallucinatory, stream-of-consciousness narrative which he believed would allow him to vividly capture the rotten heart of the American dream. Naturally Sports Illustrated, which had merely requested captions about motorcycles, had no interest in this lengthy, digressive meditation on the state of the nation. However, when Thompson showed his editors at Rolling Stone what he had been working on, not only did they encourage him to keep going but they also agreed to cover his expenses so that he could return to Vegas to attend the National District Attorney’s Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. Thompson needed a second half for his book, and the appeal of that particular event was obvious to him. “If the Pigs were gathering in Vegas for a top-level Drug Conference,” he wrote, “we felt the drug culture should be represented.”

Thompson and Acosta arrived back in Vegas at the end of April. This time, Thompson brought with him a portable recording device to capture their impressions first hand. While the pair did attend the District Attorney’s Conference, including a screening of a film called Know Your Dope Fiend, it wasn’t long before the anxiety of being constantly surrounded by so many cops started to wear on them. On their second day in Vegas, Acosta urged Thompson to take the story in a new direction. “I think we should seriously get to it and look for the American dream,” he was recorded saying. “We should just start interviewing people, like, ‘Where is the American Dream and what is it?’”

They spent the rest of the day driving around Vegas, asking for directions to the American Dream. Most people assumed they were joking. At one point, they were asked if they’d been sent on a goose chase. “It’s sort of a wild goose chase, more or less, but personally, we’re dead serious,” replied Acosta. Eventually someone told them they knew the place they were looking for, but that the American Dream had burned down three years earlier.

That summer, Thompson returned to his secluded home at Owl Farm in Woody Creek, Colorado, and committed himself to finishing his Vegas book. While he liked to present his work as if it were written in a single, narcotic-addled frenzy, in fact he polished the story over many weeks, exaggerating the pair’s drug use and condensing their two trips a month apart into a single week-long narrative. Jagged flights of imagination were a key component of Thompson’s brand of “gonzo” journalism, which he said was rooted in the novelist William Faulkner’s notion that “the best fiction is far more true than any journalism”, but there were also other liberties taken, like the references to Acosta as a “300-pound Samoan”. Although Thompson argued this was a sensible move to protect Acosta’s identity, his friend saw it differently after he was sent a copy ahead of publication by Random House’s legal team. “Did you even so much as ask me if I minded your writing & printing the Vegas piece?” he wrote to Thompson in October. “Not even the courtesy to show me the motherf***er… one would think my old buddy would say, ‘Here it is, what do you think, and do you mind?’”

Rodriguez tells me that if I really want to understand the relationship between Thompson and Acosta, I should speak to the Straight Arrow Books editor Alan Rinzler. “He’s a good man,” says Rodriguez. “He knew them both well and saw them together a lot. He’ll tell you what you need to know.” A few days later, I reach Rinzler by phone at his home in Berkeley. A key player at Rolling Stone in its early days, he also published two novels by Acosta, 1972’s Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo and 1974’s The Revolt of the Cockroach People, which featured a fictionalised version of the Salazar case.

I wasn’t deliberately trying to be nasty, it was just more fun to do something that was slightly off the beaten track

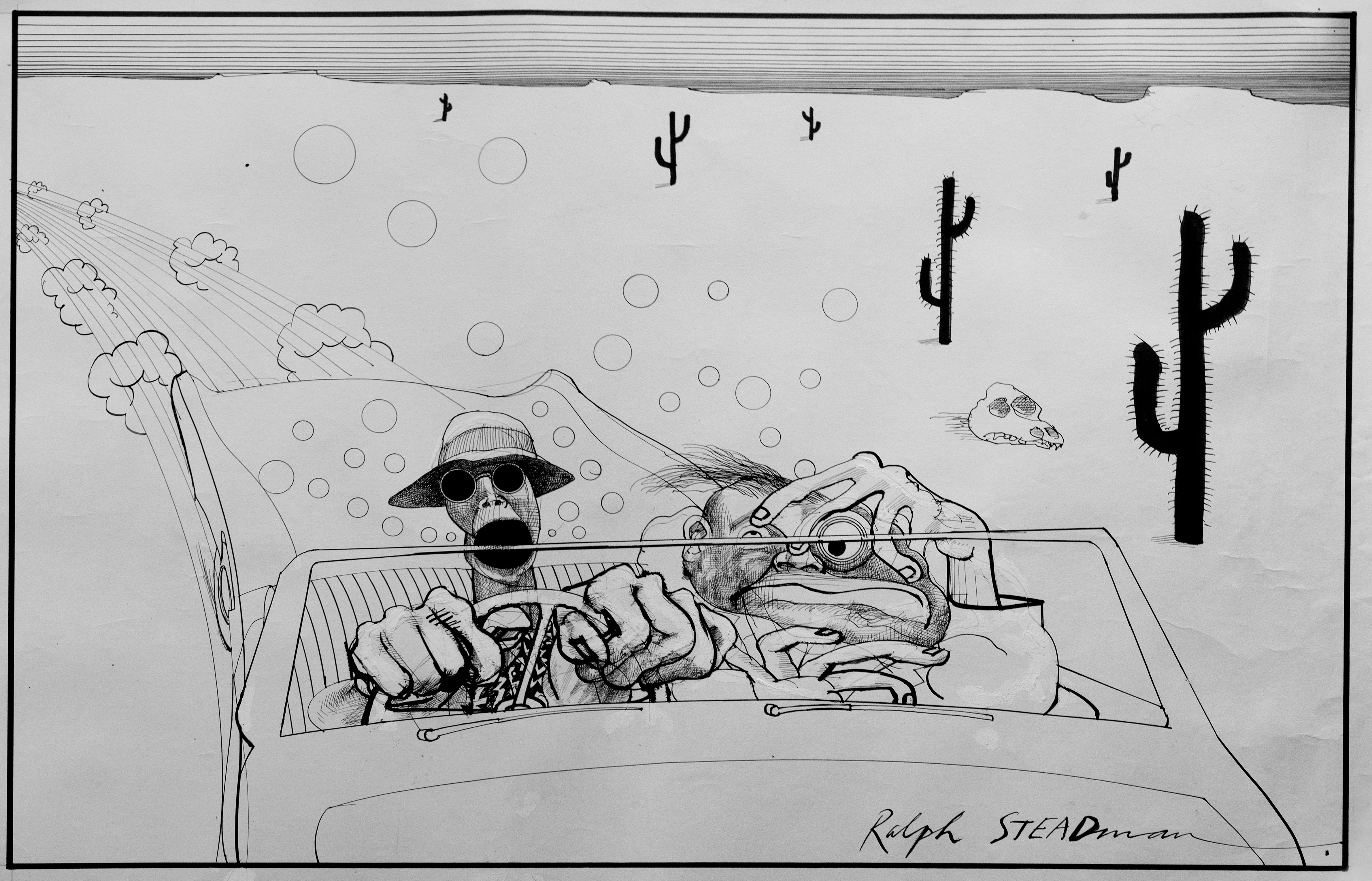

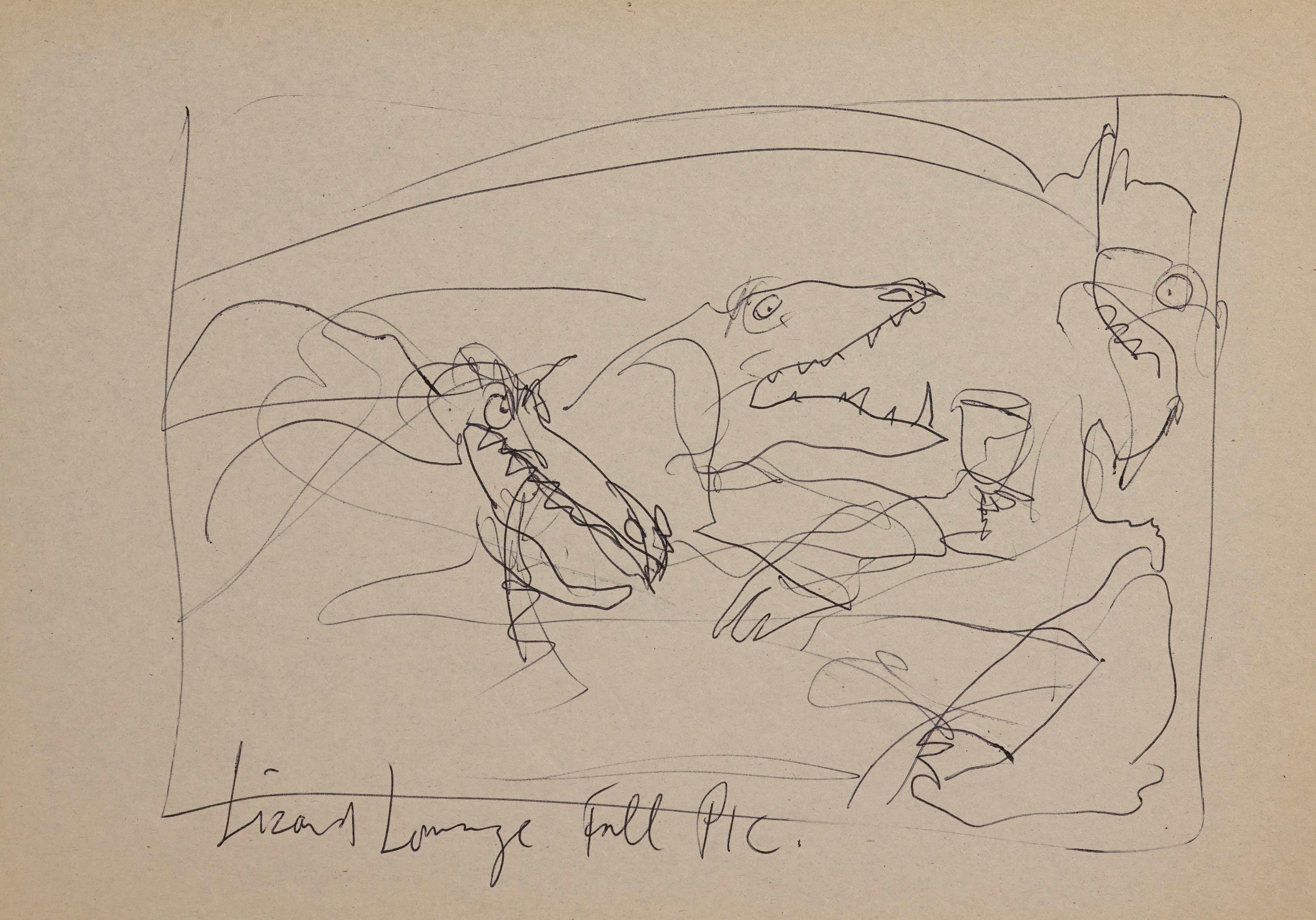

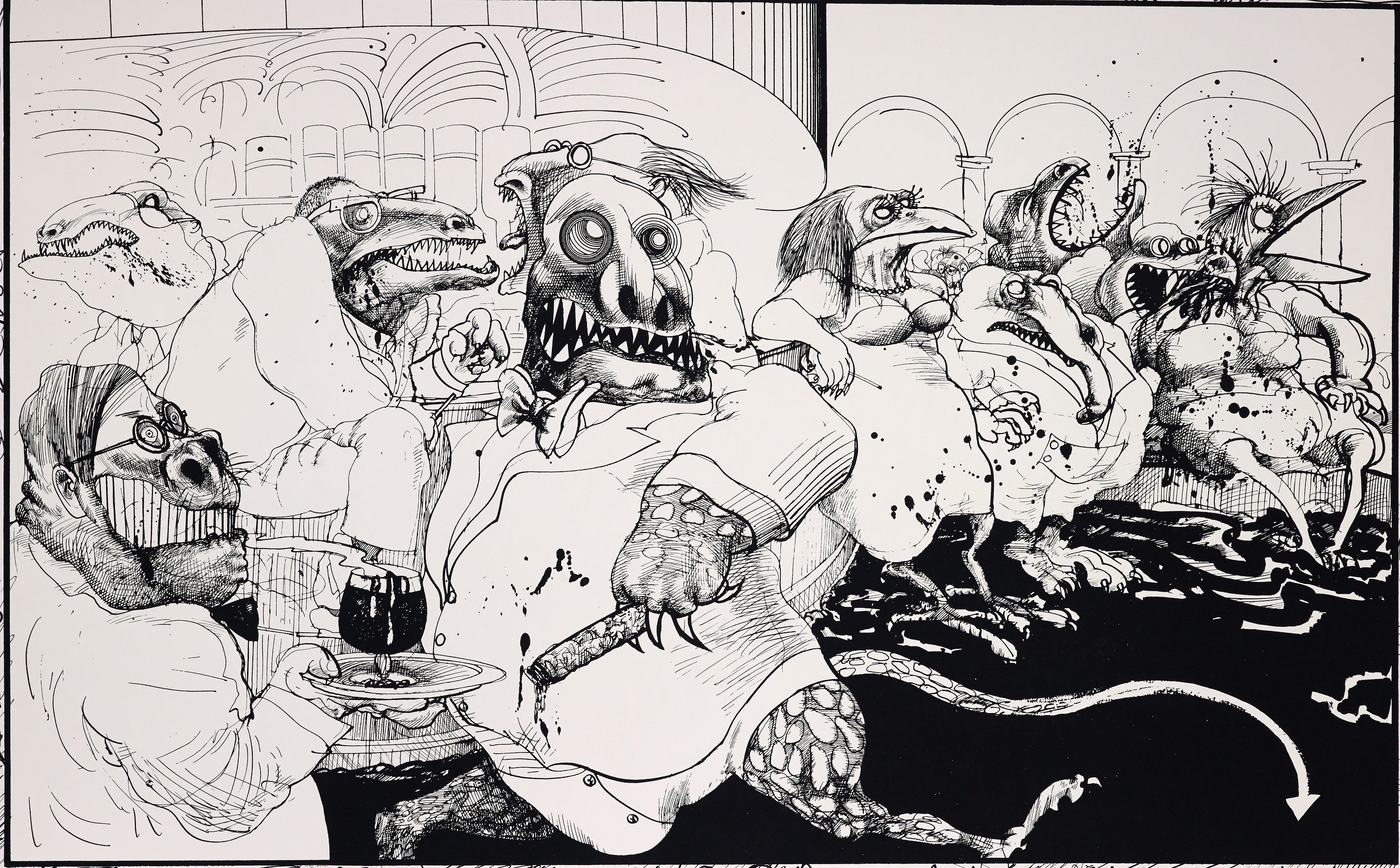

He recalls the excitement that spread around the Rolling Stone office when the editors first received and read Thompson’s prose. They devoted two issues of the magazine to publishing Fear and Loathing, pairing it with Ralph Steadman’s equally visceral illustrations. “Ralph was in that same spirit,” he says. “His art was grotesque but funny, and somehow it expressed something true about his subjects that came through as you looked at it. His work is brilliant.”

Later I speak to Steadman, who is still creating new art at 85, over a video call from his farmhouse studio in Kent. He, too, recalls the thrill of reading Fear and Loathing for the first time. “There’s such a lot of detail in it,” he says, “And it was always the naughty boy details.” He enjoyed the challenge of coming up with images that would complement Thompson and Acosta’s savage journey. “I wasn’t deliberately trying to be nasty, it was just more fun to do something that was slightly off the beaten track,” he says. “The nice thing was that we tended to be correct by being incorrect, that’s the best way to put it. Of all the people I could have met in America, Hunter was an interesting man to meet.”

After we speak, Steadman sends me a copy of a letter he received from Thompson in October 1971 after the first batch of his illustrations turned up at Rolling Stone. “The whole Rolling Stone office in SF flipped, freaked & went crazy when they opened the “London packet” and saw your drawings for Vegas I,” Thompson wrote. “And all I had to say was, “S***, that’s my man. Who else could have done it?” The letter also reveals Thompson’s delight at having completed Fear and Loathing on his own terms. “It’s already sold and heading into print. Incredible,” he wrote. “I still can’t believe they would pay me for writing this kind of mad gibberish.”

Mad gibberish it may have been, but Rinzler tells me there’s no question Fear and Loathing deserves to be regarded as a great work of American literature. “I venerate that combination of wit, humour and literary style,” he says. “Hunter chose the right words. He had the rhythm. Some of the stuff he wrote is still among the best things I’ve ever read.” He quotes the novel’s famous opening line: “‘We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold.’ It’s just great stuff. I think Hunter is still important, and rightly admired for his writing, which in his prime he was very careful and particular about. Every comma, every little word, every exclamation point had to be justified. He really did care about that stuff.”

But what of Acosta’s contribution? “I knew Oscar very well,” says Rinzler, who clearly recalls his upset after reading Fear and Loathing. “He was so furious with Hunter for what he claimed was ‘ripping him off’, first of all insulting him by referring to him as Samoan, and then by stealing his language. Oscar felt with all sincerity that the style of writing that Hunter was so famous for, and had made so much money for – he really resented that – was a rip-off of his style and his way with words and his dark humour. He really made a lot of fuss and noise, and I think he was right to some extent.”

After Acosta threatened to sue, Thompson agreed to set the record straight about the true identity of his drug-crazed attorney. While he maintained it was too late to change the text, when Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was published as a book it featured a photograph of Thompson and Acosta taken during their second Vegas trip on the back cover, along with the caption: “The author, shown here in the Baccarat Lounge of Caesars Palace, Las Vegas… with Oscar Zeta Acosta, who insists on being identified as Dr Gonzo.”

Acosta, placated, agreed to allow publication but his relationship with Thompson never recovered. In May 1974, while travelling in Sinaloa, Mexico, Oscar Zeta Acosta disappeared. Thompson did his best to find him, hiring a private investigator to uncover what had happened. Rinzler recalls being present at Owl Farm when Thompson received some fateful news. “The phone rang, and Hunter picked it up,” he remembers. “It was the detective. He said that Oscar was shot in the head on a bad drug deal and thrown off a boat off Yelapa in Mexico. It was very upsetting for everybody.”

In December 1977, Rolling Stone published Thompson’s lengthy eulogy for Acosta, “The Banshee Screams for Buffalo Meat”. Even after his friend’s apparent death, Thompson recounts how weird stories and strange rumours continued to circulate about his “allegedly erstwhile Samoan attorney”. There were claims of “Brown Buffalo sightings” everywhere from Houston to Calcutta, and an outlandish tale about him running cocaine out of Coconut Grove, Miami.

Thompson even wondered if one day Acosta might miraculously reappear on his porch at Owl Farm. “Maybe so, and that is one ghost who will always be welcome in this house, even with a head full of acid and a chain of bull-maggots around his neck,” he wrote. “Oscar was one of God’s own prototypes –a high-powered mutant of some kind who was never even considered for mass production. He was too weird to live and too rare to die.”

‘The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo’ is available to stream online

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments