Some Like Him Not: Why Billy Wilder divides opinion

A new biography, out next week, was partly written to counter the view that the filmmaker is a cynic and a misogynist. But despite his vexed relationships with female stars, Geoffrey Macnab says that his realistic gaze in films should never be mistaken for crude chauvinism

When Billy Wilder was a young journalist living on the breadline in Berlin in the 1920s, he worked briefly as a gigolo and dancer for hire. Operating out of an upmarket Berlin hotel, he candidly described the experience in an article “Waiter, A Dancer, Please!” in 1927: “I dance with women young and old; with the very short and those who are two heads taller than I; with the pretty and the less attractive; with the very slender and those who drink teas designed to slim them down; with ladies who send the waiter to get me and savour the tango with eyes closed in rapture.”

Film historian Joseph McBride’s new critical study of the filmmaker, Billy Wilder: Dancing on the Edge, argues that his “intense experience interacting with a wide variety of strangers in a Berlin hotel” was humiliating but very insightful. It helped him understand the “role of money in romantic situations” that would later become “a hallmark of his film work, the sardonic sense of love and sex turned into impersonal products through prostitution or some other kind of financial transaction, often involving impersonation or acting”.

Wilder (1906-2002) went on to become one of the greatest and most contradictory filmmakers in Hollywood history. He made some brilliant romantic comedies but his sophistication and frankness about sex, money and relationships led detractors to condemn him as an inveterate cynic. In particular, he was accused of treating the female characters in his films in a very mean-spirited and sometimes openly exploitative fashion.

The director’s voyeuristic “flying skirt” shot of Marilyn Monroe standing on the subway grating as the breeze blows up her white dress over her waist in The Seven Year Itch (1955) became one of the most famous images of the 20th century. It remains a controversial sequence. Earlier this summer, when Seward Johnson’s 2011 sculpture, Forever Marilyn, which commemorated the moment, was installed in Palm Springs, the complaints were immediate. “Some Like It Not!” and “It’s not nostalgia, it’s misogyny” read the placards carried by protesters.

Wilder, who made two movies with Monroe, famously found her exasperating in the extreme. She was never punctual. She never knew her lines. He once quipped that she had “breasts like granite and a brain like Swiss cheese”. These sound like adolescent male jibes at the expense of a vulnerable female collaborator whose reputation he should surely have been trying to protect.

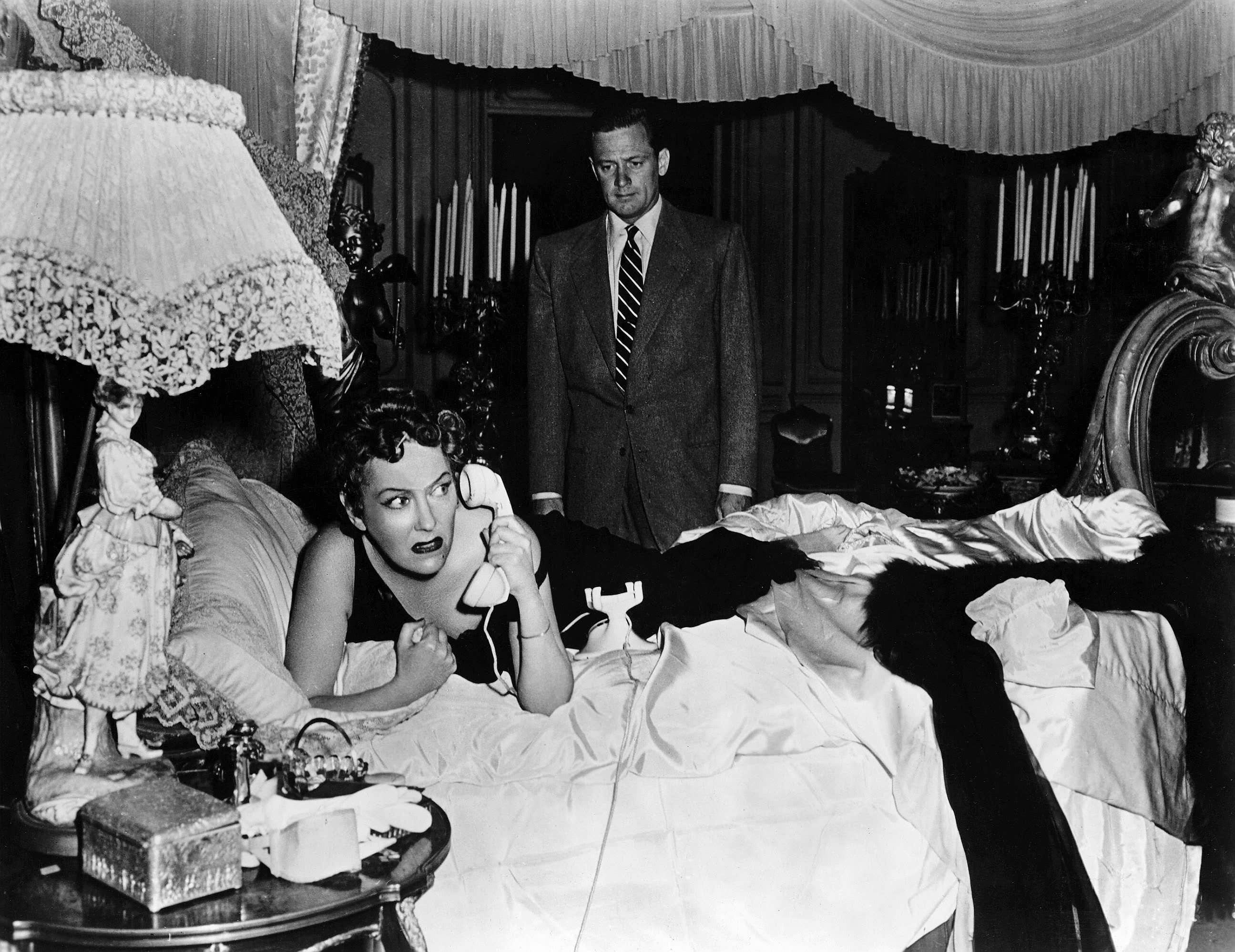

The director’s films often feature strong, destructive women with weak-willed men trailing in their wake. Take Norma Desmond, played by Gloria Swanson, the fading silent movie star in Sunset Boulevard (1950), who has the struggling writer Joe Gillis (William Holden) as her lackey and script doctor. Gillis ends up face down dead in the swimming pool.

Or look at Phyllis Dietrichson, played by Barbara Stanwyck, the seductive California housewife who puts hapless insurance agent Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) under her spell in Double Indemnity (1944). When she persuades Neff to kill her husband for an insurance pay-out, he’s the one who takes the rap.

Equally amoral is the unfaithful wife, played by Jan Sterling in Ace in the Hole (1951), who is happy for her husband to stay trapped and dying in a cave if it means a payout for her.

Even the lovely lift operator Fran Kubelik, played by Shirley MacLaine in The Apartment (1960) has a mercenary side. She is busy sleeping with the married boss while humble clerk Bud Baxter (Jack Lemmon) pines for her.

Wilder’s films also have their share of prostitutes – MacLaine as Irma in Irma La Douce (1963) and Kim Novak as Polly the Pistol in Kiss Me, Stupid (1964) – as well as jealous, manipulative female characters, for example, the reclusive, Greta Garbo-like Hollywood star Fedora, played by Marthe Keller, who refuses to shed her youth in Fedora (1978).

Women who worked with Wilder sometimes had miserable experiences. The Swiss star Keller, who was cast in Fedora after Wilder saw her opposite Al Pacino in Sydney Pollack’s Booby Deerfield (1977), likened Wilder to a dictator.

“I need that the people I work with trust and love me and then I give everything. Billy Wilder was a genius but he was not a nice man on the set. He was very funny but it was always to make fun of somebody and it was very painful to work with him,” Keller told me when Fedora was re-released a few years ago. She had grim stories about how he humiliated her during the shooting of the film in Corfu. Once, she asked if she could be shielded from the tourists swarming around the set. “He looked at me and took the speaker and said, ‘for the money you get paid, you had better do it’ – and he said the amount of money I got, in front of all the people.”

It sounds like quite a rap sheet against Wilder. He was not above a little snickering and smuttiness and he could be very caustic behind the scenes. However, any Wilder lover will counter that only the most myopic and foolish critics could accuse him of disliking women or presenting female characters in a negative light. He may have treated Keller badly – he regretted casting her – and he may have made snide remarks about Monroe, but most collaborators relished working with him.

“He is a darling, a great director and a gentleman,” Audrey Hepburn said of him.

Wilder brings depth and complexity to his female characters rarely found in any other movies of the period. Whatever the sourness of films like Ace in the Hole and Double Indemnity, they were balanced by the sweet-humoured optimism of Sabrina (1954) and Love in the Afternoon (1957), his films with Hepburn.

McBride says he wrote his new biography “partly to counter the view that he [Wilder] is a cynic and a misogynist. I don’t think he is either”.

“He does not sentimentalise women like a lot of old Hollywood films did,” McBride adds. “Wilder treats women and men both as realistic mixtures of flaws and virtues. I think that bothered some people because they weren’t used to seeing women treated realistically in movies.”

The author argues that Some Like it Hot (1959), his second feature with Monroe, is a feminist film. The two jazz musicians, played by Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis, learn to “walk in women’s shoes”, something very few male characters in other Hollywood pictures of the time even attempted. After witnessing the St Valentine’s Day Massacre and going on the run, they dress in drag and join an all-female band. Monroe, meanwhile, gives one of her most grounded, funny and touching performances as “Sugar”, the ukulele player and singer. For once, she seems like a real character, not the exaggerated male wish-fulfilment fantasy figure she so often played.

If you read the old interviews with Wilder a little more carefully, venturing beyond his sarcastic and flippant asides about Monroe’s terrible timekeeping, you’ll find that he recognised her genius. He felt it was “well worth the agony of working with her”. As he told biographer Charlotte Chandler, “If I wanted someone to be on time, to know the lines perfectly, I’ve got an old aunt in Vienna who’s going to be there at five in the morning and never miss a word. But who wants to see her?”

Moreover, Wilder was arguably the only male director Monroe ever worked with who had personal experience of being treated as a sex object. In his recently translated collection of his journalism, Billy Wilder on Assignment, which also includes the newspaper article “Waiter, A Dancer Please!” about his two months as a dancer for hire, he is nervous, sweaty and uncomfortable in his guise as a gigolo.

“In the ballroom, slender-legged women sit at small tables sipping mocha coffee. They’re putting their cups down and sizing me up, their crimson lips puckered into a honeyed, peeved smile,” he writes.

Wilder is warned that he must dance even with ladies who don’t appeal to him. “In fact, the less they appeal to you, the more honestly and conscientiously you are doing your job,” he recalled about his time as “two legs to rent”.

Years later, when Wilder was making films like Irma La Douce, Kiss Me, Stupid and The Apartment, it was clear that his experiences on the dance floor had given him a strong understanding of what his female protagonists were enduring from their clients.

Wilder was never judgemental. Female characters other filmmakers would have dismissed as seedy and corrupt low-lifes were treated with affection and humour in his films. He would always be far more sympathetic to those on the margins of society – the working girls and shady nightclub singers – than to the priggish establishment figures, such as Jean Arthur’s congresswoman in A Foreign Affair, trying to lecture them about morality. Even the haughty silent movie star languishing in obscurity in Sunset Boulevard has her redeeming qualities.

Wilder’s old screenwriting collaborator, IAL Diamond, used to refer to Wilder’s “disappointed romanticism”. What some critics saw as his cynicism was really just honesty and insight about human behaviour, which dated back to his days as a dancer for hire and freelance journalist in Vienna and Berlin in the 1920s.

He boasted in a 1963 interview with Playboy that he had once interviewed Sigmund Freud, his colleague Alfred Adler, the writer Arthur Schnitzler and the composer Richard Strauss all in the space of a single morning. Whether or not that was true, he was already a very cosmopolitan figure by the time he arrived in Hollywood in the 1930s. He’d lived through the tumult of the Weimar era and he had fled the Nazis. His worldliness was reflected in how he later portrayed women on screen. You don’t watch Wilder films expecting Anne of Green Gables or Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. His films have a far darker hue than that but his realistic gaze should never be mistaken for crude chauvinism.

‘Billy Wilder: Dancing on the Edge’ by Joseph McBride is published on 26 October. ‘Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna’ is available now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments