Inside the secretive organisation smuggling people along a 3,000-mile route out of North Korea

Almost completely stalled by the Covid-19 pandemic border lockdown, defections from North Korea have started up again this year. One group of activists tells Maroosha Muzaffar about what it takes to get people out to freedom

I’m the first one in my family to escape. Now that I know it’s not impossible, I want to bring the rest of my family out,” says Gim Sung, a defector from North Korea who risked brutal punishment to flee Kim Jong-un’s hermit kingdom in search of a better life.

Although the number of people fleeing North Korea dwindled dramatically during the pandemic, before 2020 thousands would attempt the perilous journey every year, despite knowing that they will be sent to one of the country’s notorious prison camps if they are caught.

Some, like Gim, make it safely to neighbouring South Korea, and go on to tell the tale. Others are not so lucky, at least at the first attempt, particularly if they first try crossing the large, porous land border into China, which has a policy of returning defectors en masse to its allies in Pyongyang.

“The Chinese police barged into the room and handcuffed all of us. We were returned to North Korea,” recalls defector Jo-Eun.

“My interrogator wanted me to confess to trying to defect to South Korea. I begged her to understand my situation but, instead, she grabbed my head and slammed it against a nail in the wall. I remember thinking as she took a fistful of my hair, ‘Is this my fate?’”

Jo-Eun finally escaped North Korea on her fourth attempt in 2017, in part thanks to the efforts of the non-profit organisation Liberty in North Korea.

Liberty is one a small number of NGOs that aims to help people with the secretive and highly dangerous operation to escape Mr Kim’s regime, as well as establish new lives in foreign countries.

South Korea-based Sokneel Park, one of the founders of Liberty, tells The Independent that the organisation has so far rescued at least 3,000 people.

He says North Korean millennials are much more aware of the outside world as they have unprecedented levels of access to external information, despite tight restrictions on the internet in the country. According to a 2019 survey conducted among North Korean defectors residing in South Korea, 60 per cent of the 400 people interviewed had access to international media before their escape.

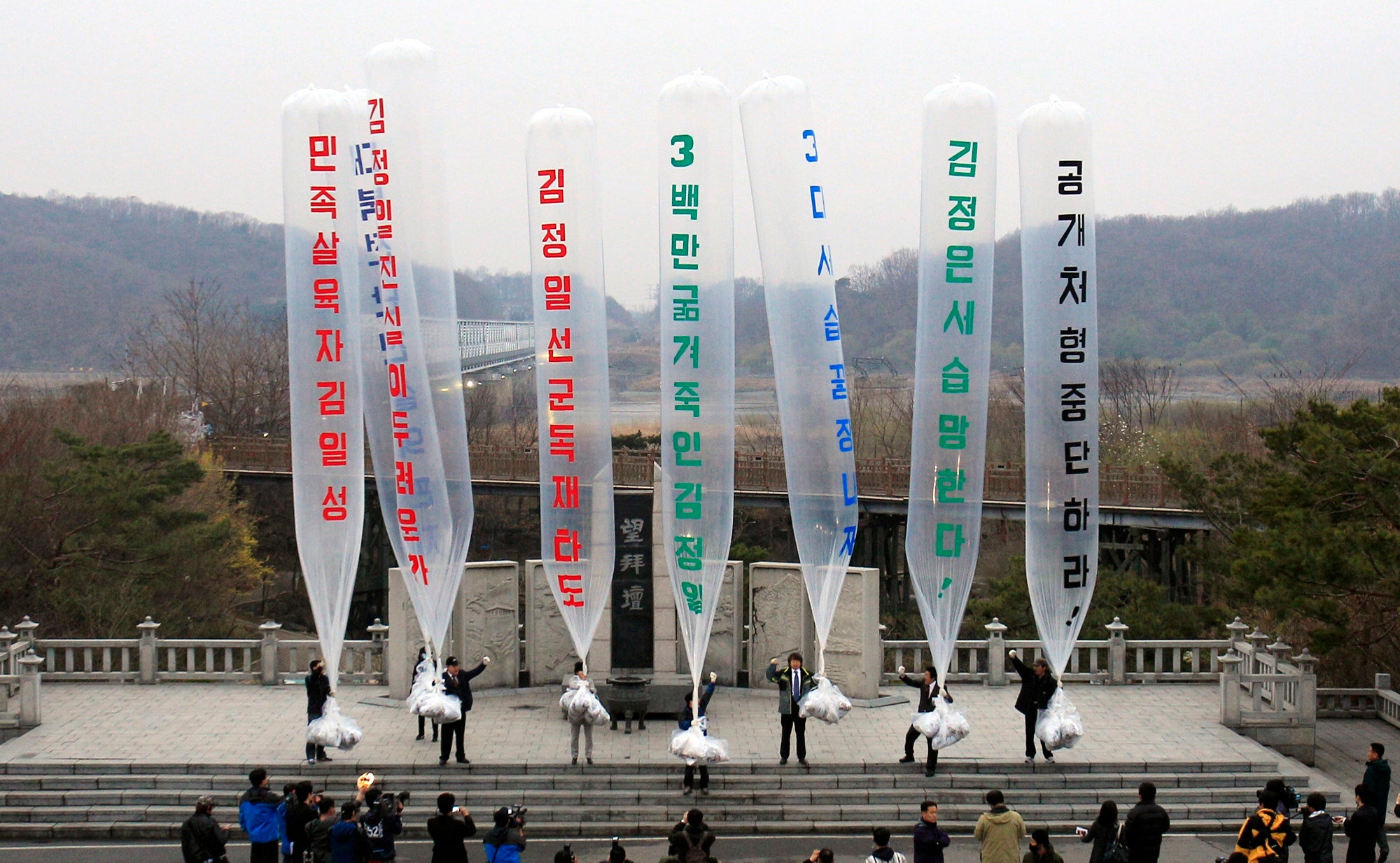

Mr Park believes the best way to increase the chances of change in North Korea is to “provide better access to information for the people there”. Once they have the information, they can fight for their liberation.

This point is illustrated by Jo, who says in a Ted Talk that once she shared more information with her family about her life in the South, their loyalty towards the North Korean regime “weakened”.

She says: “My family in North Korea didn’t believe that I was doing well here in South Korea. After I sent money and shared more about South Korean society, their loyalty to the North Korean regime weakened. I have become a pioneer of freedom for my family in North Korea.”

Data from South Korea’s unification ministry reveals a significant drop in the number of North Koreans seeking refuge in the South, plummeting from over 1,000 annually throughout much of the 2000s to approximately 100 since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

When Covid-19 struck the world, the impact of the pandemic on North Koreans was severe, with border lockdowns, increased surveillance, and restrictions hindering escapes to freedom. In late 2022, Liberty says it resumed the rescues.

But the journey to freedom is still not easy. Even if the desire to escape is there, many North Koreans might not have the resources. North Korea is one of the poorest countries in the world, though it does not publish official economic data. South Korea’s central bank estimates that the average North Korean’s gross income in 2022 was the equivalent of around £890 – just 3.4 per cent of those South.

This is where Liberty comes in, Park says. The organisation has a network of grassroots workers across North Korea, who are able to reach out to those interested in defecting and start them off on the path to freedom.

So what is this secret escape route? Park is reluctant to share the exact details for evident safety reasons, but says that the route spans 3,000 miles and originates in northern China. From there, the refugees are ultimately taken either to South Korea or the US.

The arduous journey is fraught with risks – of getting caught by the North Korean military at the border, of being repatriated by China, or just never making it out alive.

The early stages of the route are dotted with security checkpoints, state-of-the-art surveillance, as well as the simpler hazards of moving across rough terrain, often in the dead of night.

The hardest part of the journey arguably starts once refugees are across the border into northern China. There they face one of the most inhospitable jungles in the world, trekking for days through largely uncharted wilderness rife with dangerous animals and steep mountain cliff edges.

“My mind was racing, ‘What if I’m left behind and get caught?’” Jo-Eun says. Her mother had earlier taken the risk and fled the country. She recalled her mother saying that “she would rather get shot crossing the Tumen river than starve in North Korea”.

Once out of China, the refugees are taken to a Liberty safehouse in a South Asian country, where they rest from their days-long ordeal. Then the resettlement process begins, but they are still not at their final destination. Liberty organises applications for the refugees to be sent to either South Korea or the US – in what can be a lengthy process.

But there is one ritual that Liberty has: before the last leg of the refugees’ journey to liberation, they light candles on a cake, symbolising the start of their new life in a free country.

Freedom does, however, come at a cost. Those who successfully escape North Korea might never meet their families again. They also risk alienation and loneliness in their new countries.

But Park sounds optimistic. He believes that “the quicker they achieve success in their newfound freedom, the sooner they can help their families grappling with the challenges of North Korea’s brutal regime”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments