The Kim regime drove two North Korean sisters apart. One might now have disappeared for good

Two North Korean sisters who separated 23 years ago were finally reunited during the Covid-19 pandemic. Now one of them is feared to have been deported back to the North as part of a controversial Chinese ‘repatriation’ programme. Arpan Rai reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Covid-19 pandemic drove millions of families apart, but for Kim Kyu it was to be the unexpected trigger that allowed her to reunite with her long-lost sister after nearly 23 years.

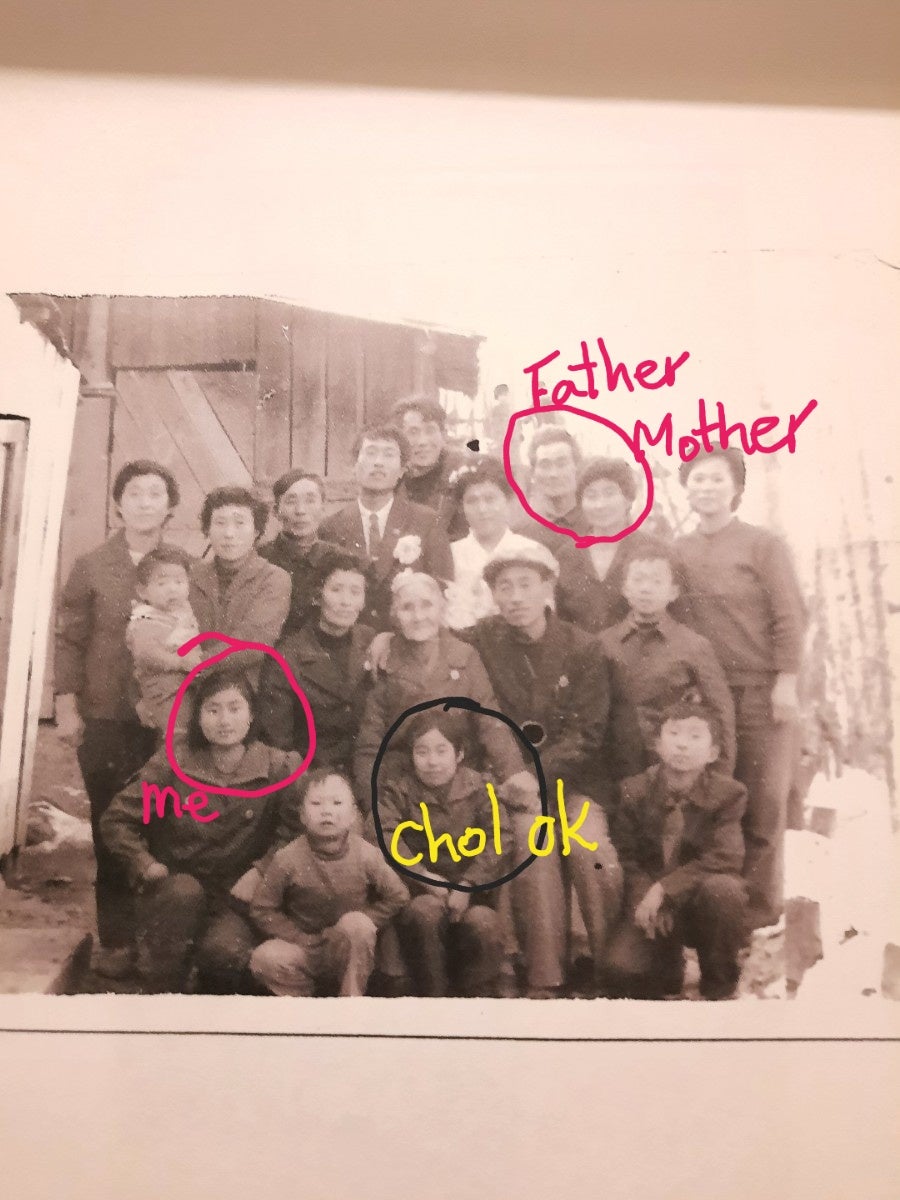

The North Korean siblings last saw each other when Kyu, 20, watched her 14-year-old sister Kim Cheol-ok being taken away by human traffickers to be sold into marriage to a Chinese man in his forties. By age 15, Cheol-ok was pregnant, and her sister lost touch with her as Kyu escaped to South Korea and then eventually the UK.

In 2020, they were miraculously brought back in touch online after a tech-savvy niece told Kyu that someone matching Cheol-ok’s description and family history was looking to trace her long-lost relatives via a post on the Chinese social media platform WeChat.

But thanks to a programme of forced “repatriations” from China to North Korea that has resumed after pandemic border restrictions finally eased, Kyu tells The Independent she fears she has lost her sister again – possibly forever this time.

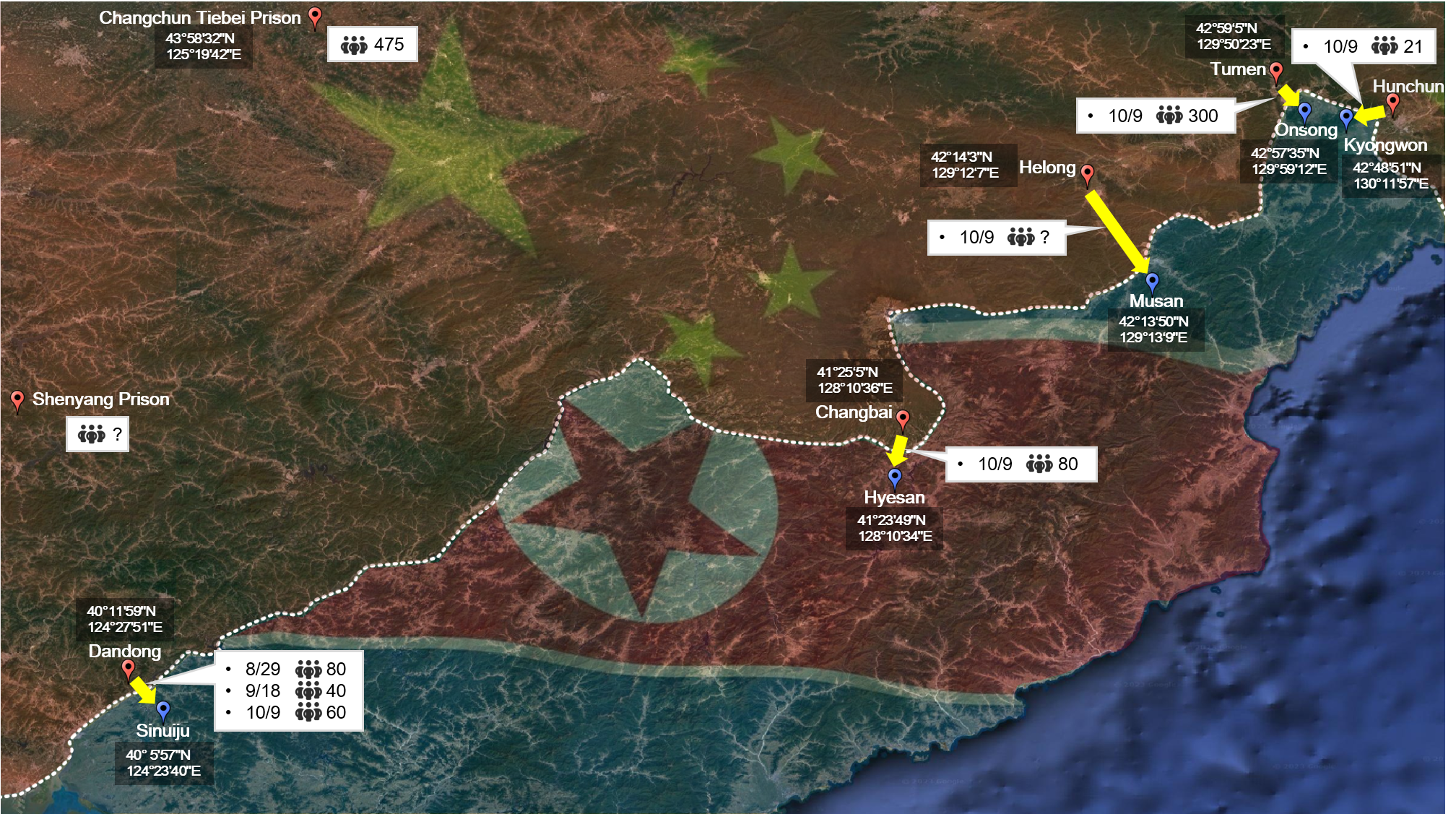

She believes Cheol-ok was one of 600 North Koreans who were abruptly shipped across the border by China in October, most likely destined for jail in Kim Jong-un’s hermit kingdom.

Sobbing uncontrollably, Kyu pleads: “Please return her to me. Nobody tells me where she is, is she safe and alive? Nobody knows what her condition is.

“There are hundreds of North Koreans like my sister held in some prisons in that country (China). The US, the UK and other nations should come forward to ask North Korea and China to release them and tell us where they have kept our loved ones,” Kyu says.

According to an investigation by the Transitional Justice Working Group (TJWG), a Seoul-based human rights NGO, as many as 420 women were among the 600 North Koreans forcibly deported to China in October, in what appears to be the largest repatriation exercise of its kind by Beijing in years.

As many as 1,500 more North Korean defectors could be deported back to the country in the coming months since Pyongyang announced the reopening of its borders in August, the TJWG warned.

Their family members have not heard from them since early October, and there are fears they could face torture, sexual and gender-based violence, imprisonment in concentration camps, forced abortions and executions.

Back in the late 1990s, North Korea under Kim Jong-il was battling a deadly famine when Kyu and her sister’s family decided to try and flee. They moved to the border and were planning to make a new life for themselves in the Chinese province of Jilin when Cheol-ok was picked up by traffickers.

After being separated from her sister for weeks, Kyu got a call from an unknown number and heard Cheol-ok’s voice on the other end of the line, informing her that she was still in China but under the control of unknown men. “I told them, give me 16 hours – I will arrange the money you need and come to China to pick her up but just keep her safe till I reach there. In the next two hours, they sold her to another man and when I called back, they said ‘wrong number’,” she says. “I begged them but they never told me where my sister went.”

For the next three or four years, Kyu tried to look for Cheol-ok, even after she had made a successful attempt to defect across the border into South Korea herself. In 2002, she lost her 25-year-old brother to prison torture in North Korea, after he was also picked up under suspicious circumstances.

Asked why she tried to get out of North Korea, Kyu says things in the country were different before 1994 under Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-un’s grandfather. But when Kim Jong-un’s father took over, things changed drastically for poor families like Kyu’s. “Food rations were halved, there was very little money and means to buy food,” she says. The regime has gotten worse still under Kim Jong-un, she added.

Over the years, Kyu continued to look for her sister online, randomly entering her name into searches to see if information about her popped up, but it was a dead end.

In January 2020, when China was in the thick of the Covid-19 pandemic which had yet to grip the rest of the world, her niece said someone by the name “Kim Cheol-ok” was looking for her family on WeChat, and has shared the name of her father, mother and sister.

The details on Cheol-ok’s WeChat post matched those of Kyu, who had now moved to the UK. She did not have WeChat in London so downloaded the Chinese social media app and contacted her sister. The authenticity of their reunion was confirmed through hastily exchanged photos. Kyu was in tears. Her sister was a mother, and settled down in married life – the arrangement had been forced, but she was generally at peace, she says.

Even in sickness, the two exchanged calls, catching up on lost years. But tragedy struck Cheol-ok once again in January 2023 when she caught Covid-19 and nearly died. “The authorities in China did not give her a vaccine or any medical help in the hospitals because she did not have [the right] papers of identification. She struggled, and over the phone, I knew I almost lost her once again,” Kyu says.

“I told her I wanted to bring her to the UK.” But it was nearly impossible with the pandemic, and in April 2023 Cheol-ok was picked up by the police in China’s Changchun city when she was on her way to South Korea to visit churches.

Kyu says no communication could be established with Cheol-ok after that point except on 9 October, when Chinese police allowed her to leave one message to her family.

“I am being sent to North Korea in two hours, call your aunt in the UK. Do something for me,” was the message Cheol-ok sent.

The investigation by the Seoul-based NGO found that the Chinese security officials operated buses and vans under heavy scrutiny and transported North Korean deportees from China’s detention centres in October this year.

At least five border crossing points in China’s Jilin and Liaoning provinces were used to deport the defectors back to North Korea. These include Dandong to Sinuiju, Changbai to Hyesan, Helong to Musan, Tumen to Onsong and Hunchun to Kyongwon, with at least 300 expected to have been sent over using the Onsong to Tumen crossing, the TJWG said.

The information blackout in North Korea has left families with no idea what happened to their loved ones in the weeks since the deportations.

“The world should help my sister and hundreds of North Koreans like her who are in [an] unknown condition right now,” Kyu tells The Independent.

Officials who worked on the investigation say that at least 1,100 more North Koreans are estimated to be held in Chinese detention centres. “They are ‘sitting ducks’ who could be deported back to the murderous regime which they fled from at any moment,” says Ethan Hee-Seok Shin, a legal analyst at TJWG.

He says North Korea encourages the deportations because it wants to deter its people from leaving the country.

“China’s central government sees the issue from mostly a geopolitical perspective – that it is in Beijing’s interest to maintain a good relationship with Pyongyang and, more importantly, ensuring that the North Korean state does not collapse from a mass exodus of its people,” he says.

“We urge the UK and US governments to condemn and take actions against China's recent forcible repatriation to prevent many more North Koreans vanishing into the abyss on their forced return to their homeland,” he says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments