Books of the month: From Sebastian Faulks’ The Seventh Son to Zadie Smith’s The Fraud

Martin Chilton reviews the biggest new books for September in our monthly column

The assassination of President Kennedy in November 1963 sent shockwaves around the world, although reactions clearly varied. In A Northern Wind: Britain 1962-1965 (Bloomsbury), the latest instalment of David Kynaston’s marvellous history of our isles, the contrasting micro and macro concerns are clear in an exchange between future comedy writer Laurence Marks and his father, after hearing the news on the radio in their Finsbury Park home. “My dad thinks the Soviets killed the President and there will be another world war,” Marks wrote in his diary. “I’m not worried about the war, I’m worried whether the Arsenal-Blackpool match will be called off tomorrow.” Life always goes on. The game was played. Arsenal won 5-3.

Kennedy’s successors include the odious Donald Trump, but I doubt Trump wants to imagine all those federal prosecutors as circling sharks. In Robert Peckham’s Fear: An Alternative History of the World (Profile Books) we are told that “adult film actress” Stormy Daniels, who claims she had an affair with the former US president, was struck by Trump’s “terror of sharks”. She said he used to watch Shark Week on the Discovery Channel, just to sit there and watch in “fascinated horror”.

If you want some fictional scares, then Helen Grant’s Jump Cut (Fledgling Press) is a chilling, highly atmospheric tale of 104-year-old Mary Arden, the last surviving cast member of a notorious lost film called “The Simulacrum”, who is holed up in a haunted Art Deco mansion.

Pizza, which means “something crushed flat” in the Italian culinary lexicon, started in Naples as “a dirt-cheap, palatable street food,” according to Anya von Bremzen in National Dish: Around the World in Search of Food, History and the Meaning of Home (One). As well as Naples, she offers an entertaining look at Tokyo’s ramen and rice, Seville’s tapas, and Istanbul’s Ottoman potluck.

Finally, if you have the stomach to read a calm, dispassionate analysis of why Brexit is such “a mess”, then Peter Foster’s What Went Wrong With Brexit and What We Can Do About It (Canongate) is an excellent quick explainer. Perhaps Jacob Rees-Mogg’s nanny can put on the audio version as she spoon-feeds him Eton mess.

Novels by Sebastian Faulks, Zadie Smith and James Ellroy, as well as non-fiction from Mick Brown and Ros Atkins, are reviewed in full below.

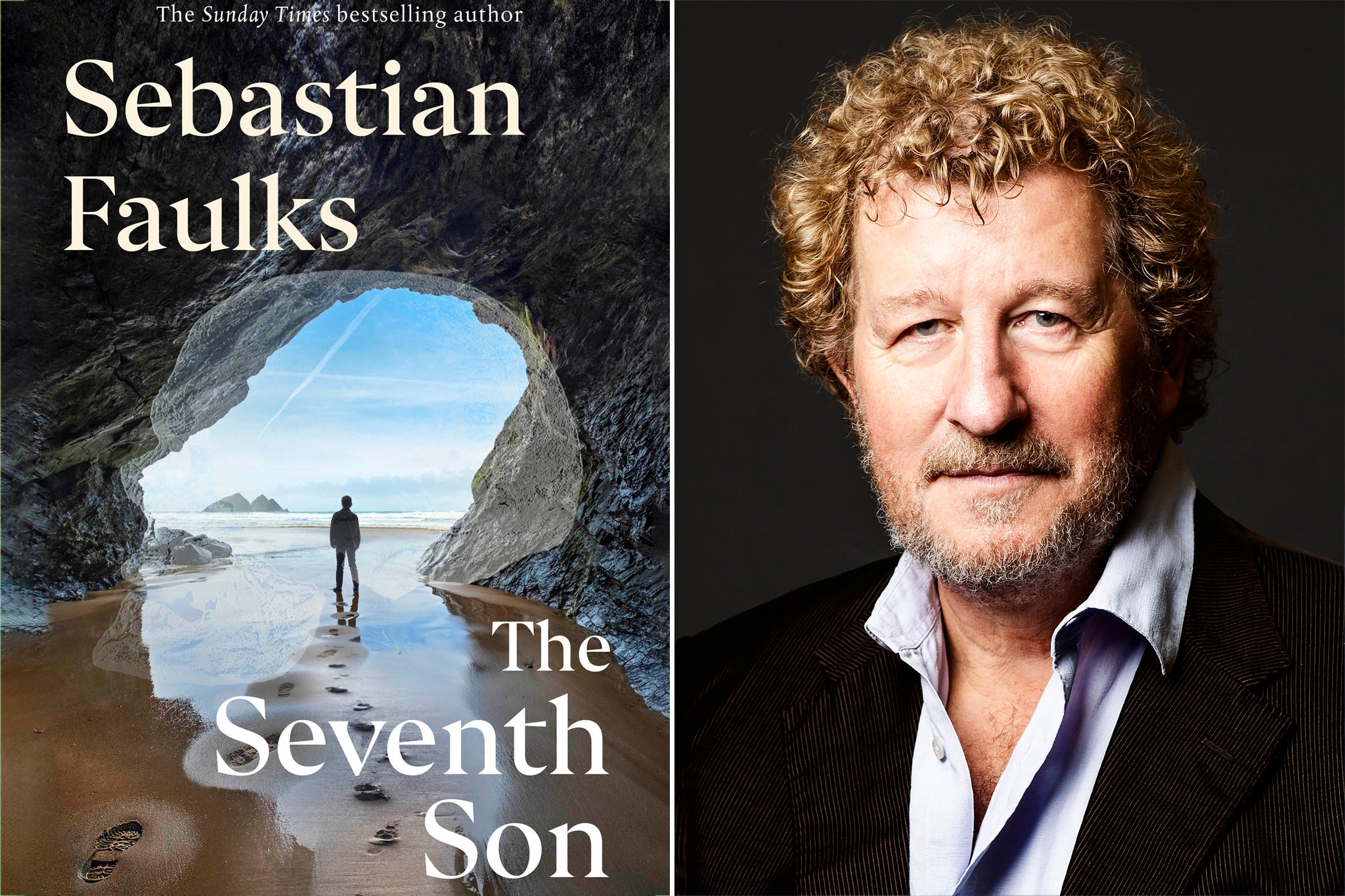

The Seventh Son by Sebastian Faulks ★★★★★

Warning: contains small spoilers.

“No one can play God. Not even rich men,” American academic and surrogate mother Talissa Adam tells the creepy, Australian-born tech billionaire Lukas Parn, after he recklessly and dishonestly stretches the boundaries of ethics by genetically engineering a child called Seth (another Biblical name), who is a hybrid of modern human and Homo sapiens Neanderthal.

Sebastian Faulks’s beautifully written novel is set over four parts – in 2030, 2031, 2047 and 2056 – and it is a stunning meditation on responsibility, decency, love, the intricacies of consciousness and what makes us human.

Needing money from the Parn Institute, Talissa flies to London to carry a child for Alaric Pederson, and his wife Mary. But, as Dr Richard Kimble finds out to his cost in the 1990s thriller The Fugitive, sometimes devious men “switch the samples”. In this case, it is Parn’s sperm swapping that leads to disaster, dishonesty only discovered a decade later when Talissa secretly commissions a DNA test. Her confrontation with Parn is memorable.

Over the course of a quarter of a century, we follow what happens to Seth (is it just coincidence that someone 51.5 per cent Neanderthal supports Crystal Palace?), as Faulks skilfully evokes the painful consequences for a likeable young man whose life becomes global news. The loneliness and persecution Seth faces is heartbreaking (“my best friend was the talking car,” he tells Talissa) and the set piece of Seth appearing on a mid-21st-century chat show is both funny and excruciating.

The Seventh Son lingers long in the mind and provokes so many reflections on survival, the existence of the soul and the (surely) futile quest to understand the strange and fragile nature of human existence. The novel also raises interesting questions about identity and growth: is the child version of someone you love just a prototype lost in time?

Setting a book in the future also allows Faulks moments of droll, incisive humour, especially in reflections about our own shabby present (Boris Johnson is a forgotten figure, except for his hair), although climate change isn’t a big aspect of this imagining. Faulks conjures a future in which Sandra Bullock is considered one of the “greats” of the 1990s and press officers delegate their work to virtual assistants.

Not all the scientists in the story are venal, incidentally, and Parn doctor Catrina Olsen is arguably the moral compass of the novel. Although The Seventh Son examines deep and dense themes about science and humanity, it is also a page-turning treat. I read the 350-page book in two sittings and was eager to find out how Faulks would find a neat ending to this compelling story. The finale, set on a remote and desolate Scottish island that feels “like the end of the world”, is unsettling and disturbing, yet oddly comforting.

‘The Seventh Son’ by Sebastian Faulks is published by Hutchinson Heinemann on 7 September, £22

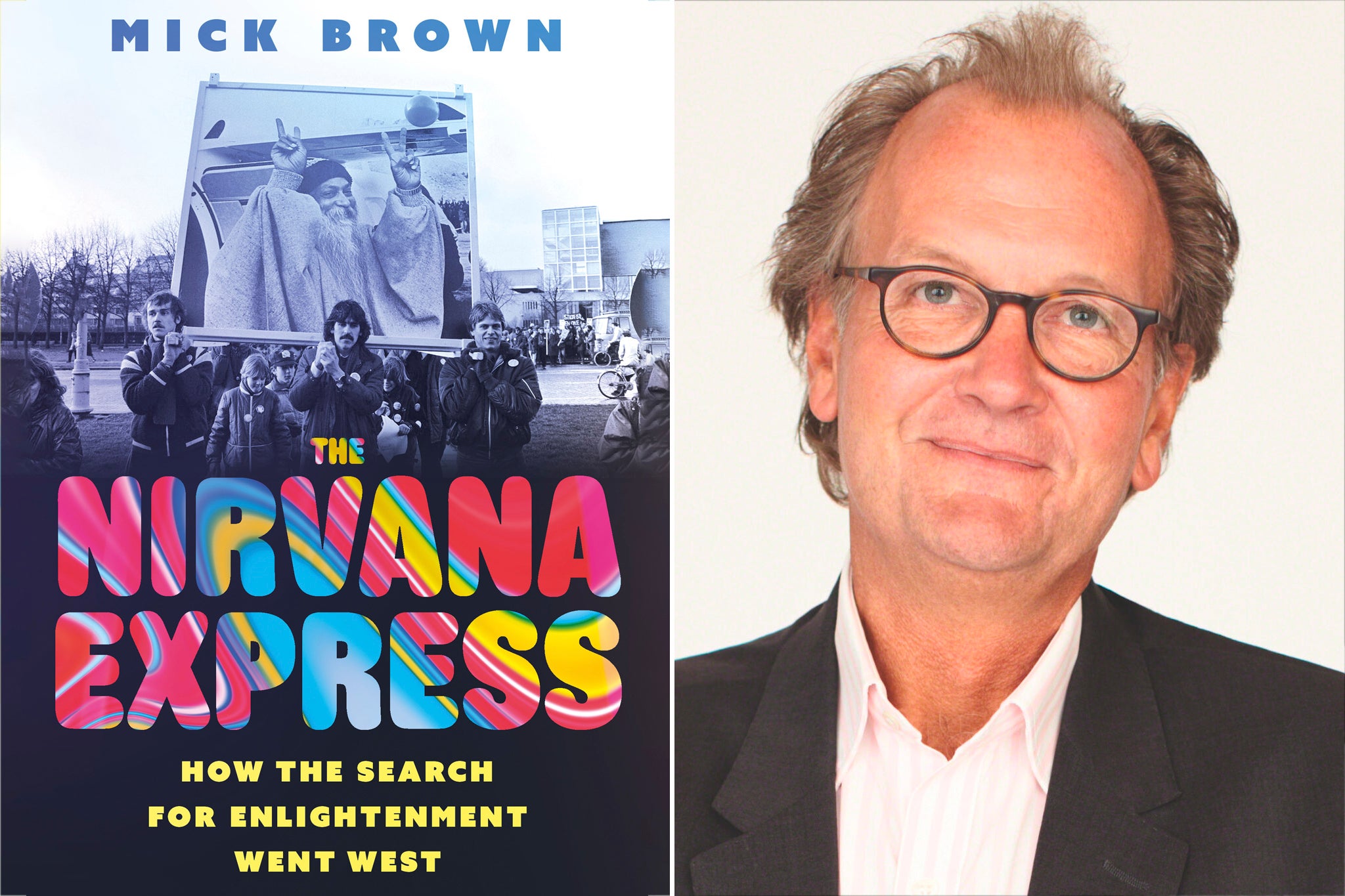

The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment Went West by Mick Brown ★★★★★

In 1968, Frank Sinatra received a telegram from his estranged wife Mia Farrow, telling him she was leaving the Maharishi’s ashram in Rishikesh because she was “fed up with meditation”. One can only imagine the disdainful look on his face. It’s hard to see Sinatra joining The Beatles (who were there at the same time as Farrow) on a quest for enlightenment in India. The Fab Four’s trip is just one part of Mick Brown’s fascinating tale of the West’s love affair with spiritualism.

I worked with Brown at The Daily Telegraph and count him among the very elite tier of modern journalists. He brings all his skills for research, judicious analysis and eloquent writing to a thoroughly engrossing subject. His description of appearances are so evocative. For example, Allan Bennett, the first Englishman to become a Buddhist monk, is described as “a tall, stooping, cadaverous man with a shock of dark hair and deep-set eyes”.

Brown balances reports of the prejudices and racism of the British view of the Indian holy man (gurus were described as “pantomime” figures) with an account that offers rich insights into the appeal of hunting “a spiritual Eldorado”.

The book is full of intriguing characters: Annie Besant, the eccentric occultist Aleister Crowley, Greta Garbo, the Beach Boys, Timothy Leary, an LSD-tripping Aldous Huxley, Beat writers Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac and, of course, The Beatles. The account of the infatuation John Lennon and George Harrison had with Transcendental Meditation is enriched by Brown’s own interview with Harrison. Brown is also even-handed with controversial figures such as the Maharishi, a man who was infatuated with fame, self-publicity and money.

One of the most memorable characters in the book is the 1950s writer and Hollywood personality Mercedes de Acosta, who had affairs with Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. She sought answers to life’s big questions from guru Meher Baba. When she told him about her poor health, he asked her to repeat his name 7,000 times a day. “How effective this treatment proved is not recorded,” is the author’s deadpan punchline.

De Acosta is one of a whole cast of stimulating personalities who appear throughout the 350 pages, going back to Victorian times, and Brown expertly stitches in hundreds of telling details about the major and minor figures in the story. It’s another factor that makes The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment Went West such a masterful, compelling piece of history.

‘The Nirvana Express: How the Search for Enlightenment Went West’ by Mick Brown is published by Hurst & Company on 7 September

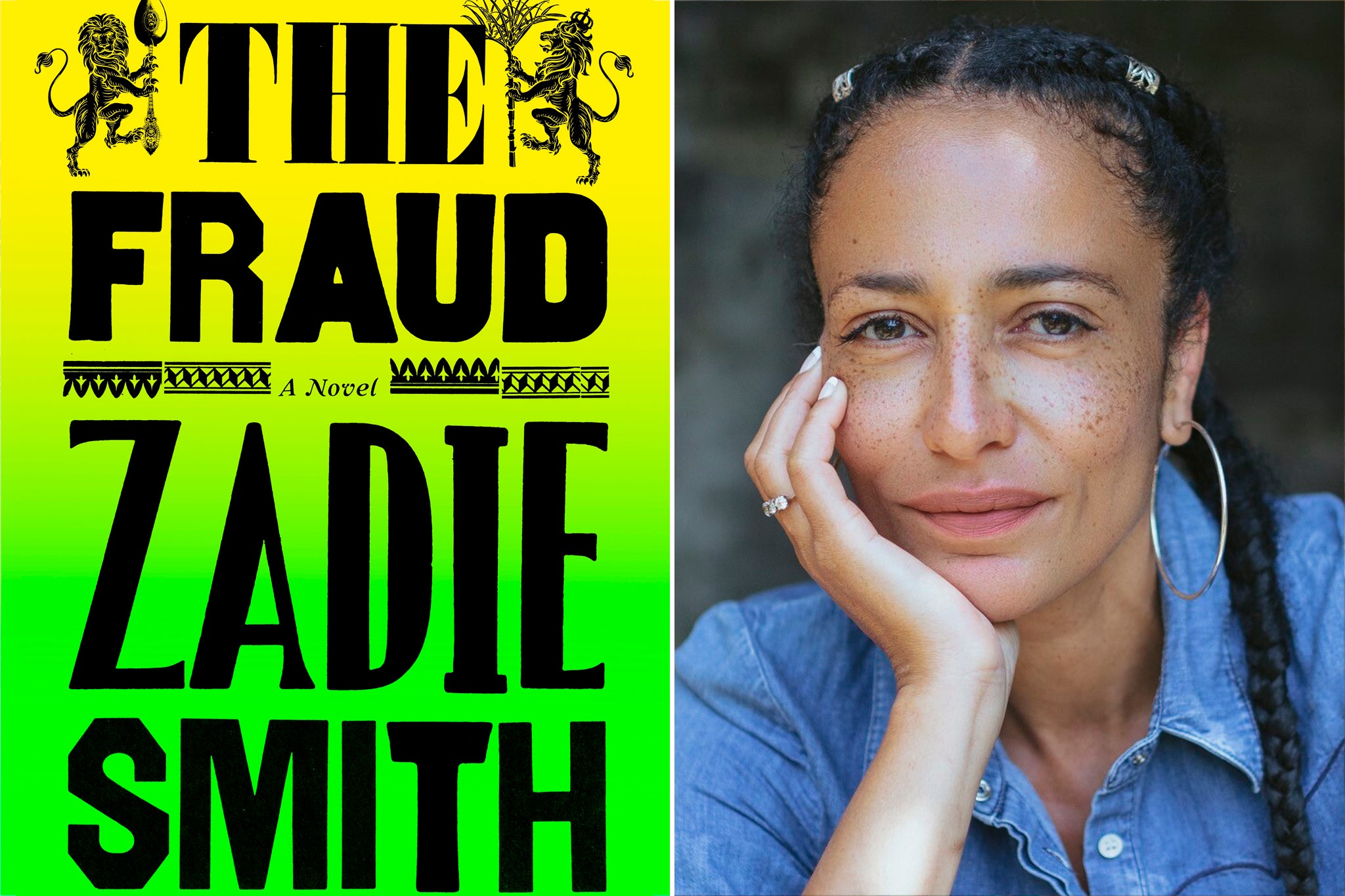

The Fraud by Zadie Smith ★★★★★

“One of the complications of managing decline was nostalgia,” writes Zadie Smith in her latest novel, The Fraud. Set in Victorian times, the book is her first foray into historical fiction – but it also has so much to say about our present disintegrating little island and its obsession with sentimental reminiscence.

The Fraud is a complex mosaic of interweaving plots, set around the “Tichborne Claimant” battle, a legal cause célèbre in the 1870s and a case Smith says she has been thinking about for more than a decade. The trial of a man claiming to be Sir Roger Tichborne, heir to a fortune who was thought lost at sea, lasted 140 days and consumed the attention of the public. Was he really a baronet or just an imposter, a butcher from Wapping?

The reader sees the trial through the eyes of widowed Scottish housekeeper Eliza Touchet, who is living with her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a once famous writer who is now in a permanent professional slump, churning out tedious, unreadable historical fiction. Smith captures his personal decline in one brutal passage, describing how a “handsome young buck” of the 1830s has turned into “this whiskery, jowly, dejected, old man”.

In her depiction of a bustling Victorian household – Eliza has a secret love affair with Ainsworth’s wife and generally serves as muse to the eccentric writer and advice-giver to his daughters – Smith creates a compelling picture of a rumbustious place, fulfilling her aim of rescuing the past “from this flat view we have of it”.

Ainsworth, author of 41 archaic clichéd novels, is a benignly ludicrous man and Eliza’s erratic relationship with him is deftly observed. Smith pokes fun at the absurdities of other revered Victorian writers. The Fraud also has a notably spiky portrayal of Ainsworth’s friend Charles Dickens, presented here as a self-satisfied, obsequious man, always playing a part and “two-faced” in his dealings with friends.

Smith, who has previously written everything from essays and short stories to playscripts, and whose enthralling, intricate, multi-plotted novels include White Teeth, NW and the Orange Prize-winner On Beauty, admitted she started out intending to write a “comic” historical novel. However, post-Trump, post-Brexit, it developed into one that was, in her words, “more like life: comic and tragic”. The brilliantly witty and melancholy two-page chapter ‘”The Brighton Years, 1853-67” is a sublime example of her ability to bridge both emotions.

True Londoners tend to remain attached to the old districts in which they were born (or grew up) and you can tell that writing about her native city and its past is intensely meaningful for Smith. She makes London a commanding presence in The Fraud, although a time when Edgware Road had fields as far as the eye could see and Kilburn was “pretty” seem a fanciful concept now.

The novel pulls off the trick of being both splendidly modern and authentically old, helped by melodramatic Dickens-style chapter headings such as “All is Lost!”. The characters, including pernicious lawyers, writers disfigured by egotism and milksop campaigners, are varied and entertaining and Smith, in the way of a Victorian stereoscope, ties together bountiful images, personalities and dramas into a single dazzling three-dimensional picture. The Fraud is the genuine article.

‘The Fraud’ by Zadie Smith is published by Hamish Hamilton on 7 September, £20

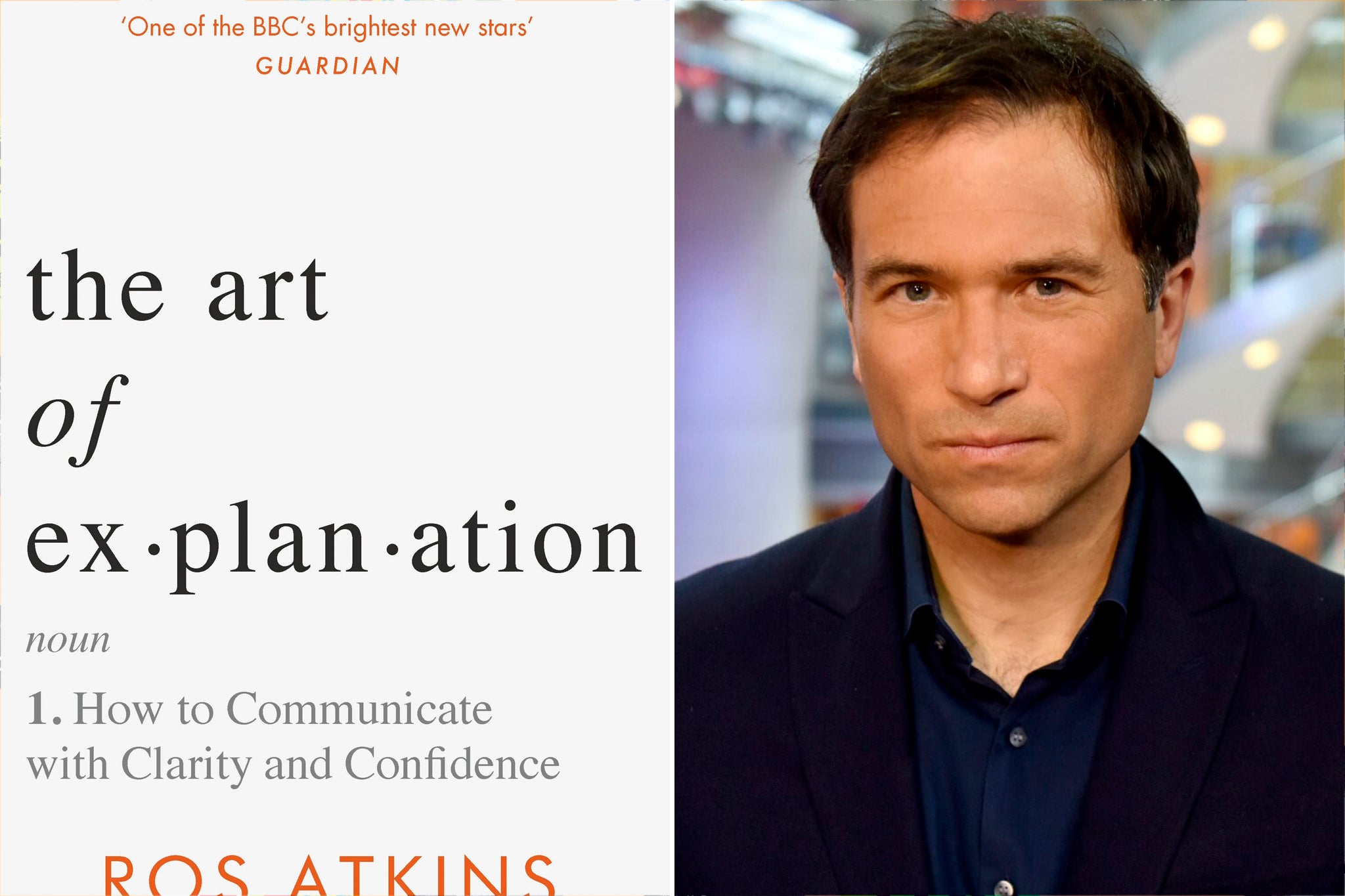

The Art of Explanation: How to Communicate with Clarity and Confidence by Ros Atkins ★★★☆☆

If you’ve watched Ros Atkins deconstruct the news of the day on his BBC show Outside Source, then you will probably agree with journalism Professor Jeff Jarvis’s assessment that “Atkins has made a practiced art of explanation”. I’m not big on advice or self-help books, but The Art of Explanation: How to Communicate with Clarity and Confidence ticks a lot of boxes.

Atkins comes across as personable and is candid about his own past setbacks – disappointing job interviews; a spell after graduation when he was unemployed and low on cash and confidence – and I liked that he is a self-confessed “magpie” when it comes to constantly looking for tips and recommendations to help him better understand a subject.

It is no coincidence that words such as “precision”, “preparation” and “clarity” come up frequently in this lucid and detailed book, which offers good advice on memory, presentation and a range of techniques to put forward the best explanations in both verbal and electronic communication. And, for added validation, it turns out Atkins is a big Joni Mitchell fan.

‘The Art of Explanation: How to Communicate with Clarity and Confidence’ by Ros Atkins is published by Wildfire on 14 September, £20

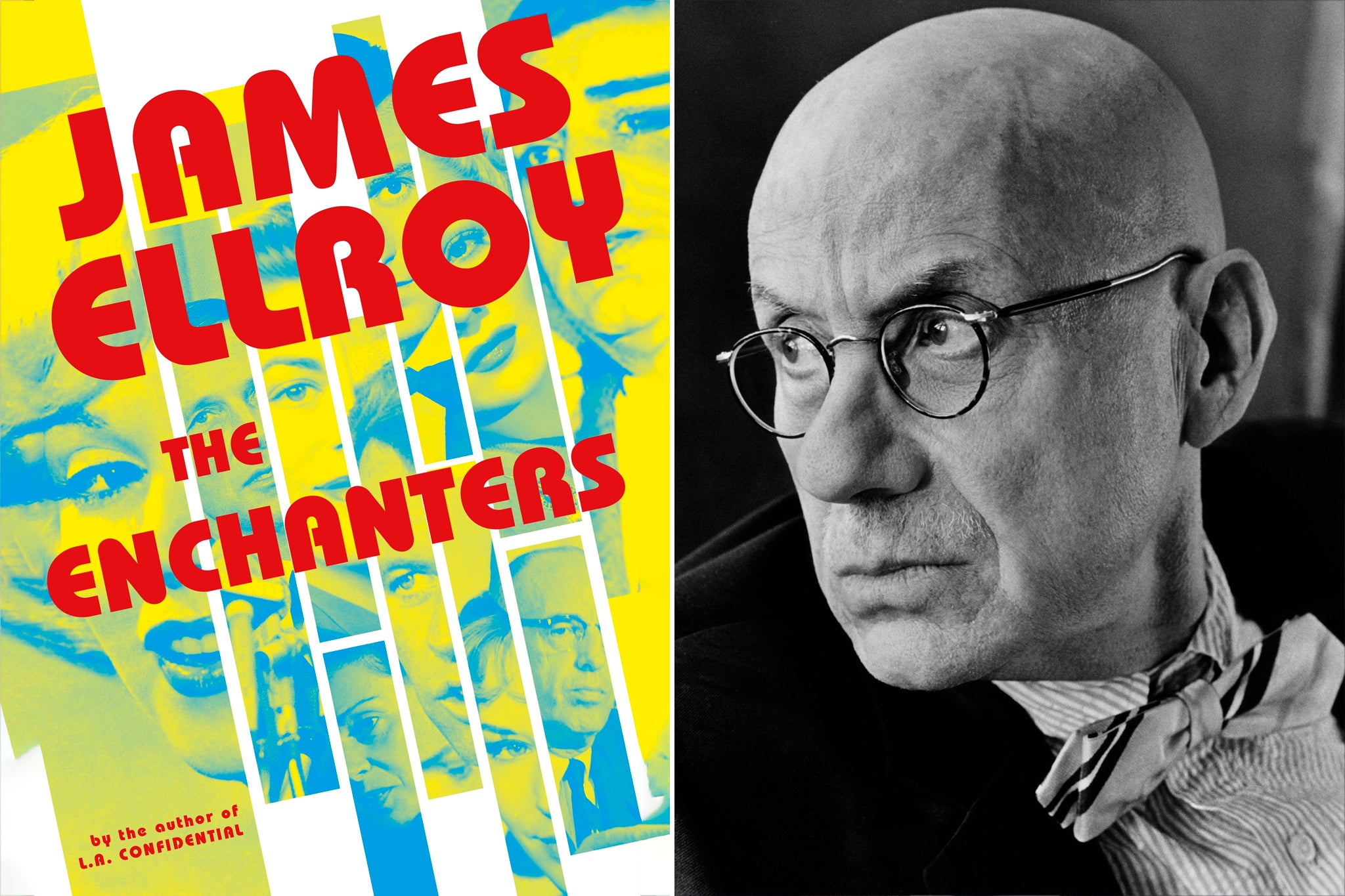

The Enchanters by James Ellroy ★★☆☆☆

In The Enchanters, the 17th novel from the author of classic crime novels The Black Dahlia, LA Confidential and White Jazz, James Ellroy again revisits some of his old themes, such as the suspicious death of Marilyn Monroe and the role of the Kennedys.

The hero-narrator of The Enchanters is the real-life and thoroughly loathsome Freddy Otash – described by Ellroy as “tainted ex-cop, defrocked private eye, dope fiend, and freelance extortionist” – and the novel serves as another exposé of corruption in golden-age Hollywood. There are plenty of sex fiends, low-rent criminals, goons and “f*** pads”.

The Enchanters is meant to be a thrill ride – with alliterative triplets such as “I was itchy, antsy, adrenalized” – set in a sweltering Los Angeles in August 1962. There are glossaries at the back with explanations of police and criminal terms (“bait girls”, for example) and a list of the main characters, with notes on people including “Motel Mike” Bayliss. Ellroy, who turned 75 in March, writes that “women crave Mike’s handsome ass”, something that feels like old man writing. He also details Monroe’s fall into sleaze. Does anyone now care what Monroe thought of JFK’s penis?

I do wonder whether all the subjects that inspired and consumed Ellroy as a young man just won’t intrigue modern readers. I get the appeal of his energetic, provocative and profane style but The Enchanters didn’t do it for me. It was like watching an ageing Sixties crooner trying to belt out a saccharine hit from half a century ago. Sometimes it’s better to leave those tight-leather trousers in a box in the loft.

‘The Enchanters’ by James Ellroy is published by Hutchinson Heinemann on 21 September, £22

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments