Man Utd, the Munich air disaster, tragedy and triumph: writer David Peace on one of sport’s most powerful stories

The novelist has taken pivotal British events – from the Yorkshire Ripper murders to the miner’s strike – and pivotal British football managers – Brian Clough and Bill Shankly – as inspiration. He tells Martin Chilton the poignant personal reason that he based his latest on the 1958 Munich air disaster that claimed the lives of eight Manchester Utd players

The newspaper billboards that screamed “United in Plane Crash” shocked millions of people to the core on a freezing day in February 1958. Among those who remembered that bombshell moment was the author David Peace’s father, Basil, who as a young trainee teacher in London found himself standing stunned outside a newsagent on the King’s Road. A British European Airways flight carrying Manchester United home from a European Cup fixture in Belgrade had refuelled in Munich and then crashed on an icy runway during a third attempt at a take-off. The tragedy cost the lives of 23 people, including players, club officials, journalists, air crew and passengers, and is the subject of Peace’s haunting new novel Munichs.

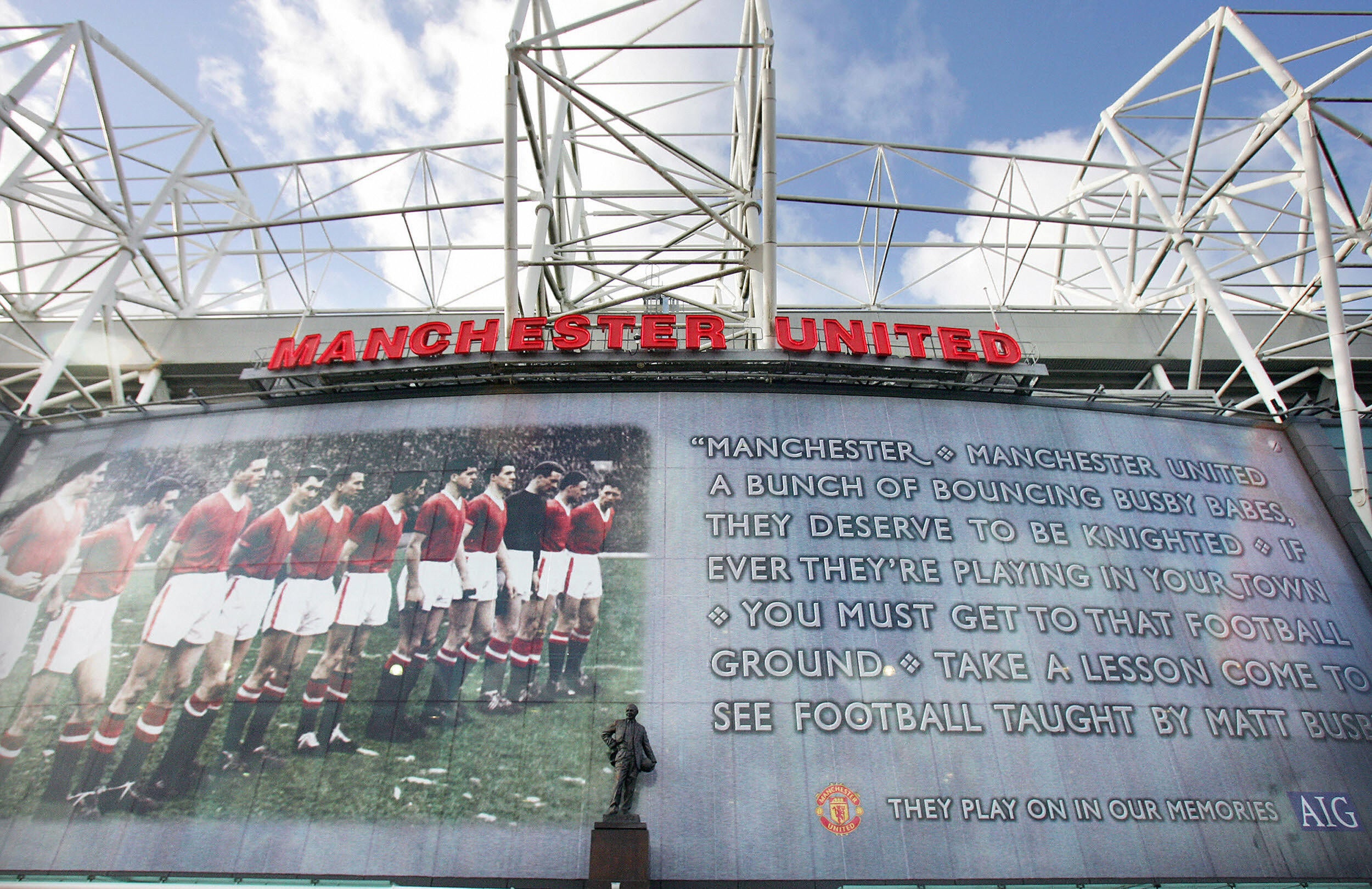

“It’s a story that should be essential to the working-class history of Britain,” says Peace, speaking in a Zoom interview from his long-term home in Tokyo. “That disaster and how the team triumphed over it is the thing that makes Manchester United special. It makes them different from any other club and, to me, it should be remembered as a badge of honour.”

Munichs, a deft blend of fiction and true story, was written in six months, entirely in Japan, in the aftermath of the pandemic, and following Peace’s father’s death in 2022 from vascular dementia. As a result, the novel is infused with a heavy sense of both grief and respect. “I had been chipping away at a book about Harold Wilson for about 20 years, but I just couldn’t get back into it in the way I wanted. I was sitting in a pub on my own one afternoon, feeling a little sorry for myself, and thinking about my father. Looking back, I realised that probably 50 per cent of our conversations were about sport, and the majority of them were about football. The book about Munich was a way to keep the conversation going.”

Born in Dewsbury in 1967 and brought up in Ossett, West Yorkshire, Peace is one of our greatest literary chroniclers of working-class Britain. He has written twice before about football – 2006’s The Damned United, about Brian Clough’s 44-day reign as manager of Leeds, was turned into a film starring Michael Sheen, and 2013’s Red or Dead was a fictional portrait of the legendary Liverpool manager Bill Shankly. What’s the appeal? “The history of British football is filled with so many great narratives and characters,” he says. “I could have written about Herbert Chapman or Stan Cullis or Bill Nicholson or Jock Stein, for example. These were all men who had come from extremely poor backgrounds, often with little formal education, and who succeeded not only through their physical abilities and strengths, but through the power of their intellect and character, and who would not allow themselves to be constrained by the strictures of the class and time into which they were born.”

Peace himself is a Huddersfield Town fan, like his father and grandfather before him. Throughout his childhood his dad would reminisce about the remarkable players he’d seen in action – including Stanley Matthews and the great Tottenham double-winning team of 1961, whom he’d seen regularly while holding a season ticket at White Hart Lane. However, the footballers his father talked about most were the Busby Babes, the dazzling young side ripped apart on the fateful flight that left gravely injured manager Matt Busby in a desperate battle for his life.

“Dad talked so much about the Busby Babes, a team he first saw in 1953 at the old Huddersfield Leeds Road ground. My father was 16 and United’s prodigy, Duncan Edwards, was just 17. Dad said that after that day he just gave up football and concentrated on playing cricket, because he had just never seen anything like the young Edwards,” Peace adds, with a smile. His father also treasured the memory of seeing United’s last game in England before the crash, a famous 5-4 win at Arsenal.

Part of what makes Munichs so affecting is that as well as being a haunting story of the eight players who were killed, including Edwards, it explores with real empathy other lives affected by the tragedy. “The crash pretty much wiped out the best sports writers of a generation,” laments Peace, referring to journalists including Donny Davies of the Manchester Guardian and Frank Swift of the News of the World. The tale of the pilot Jim Thain, who was made a scapegoat by the German investigators and his own British European Airways airline, is also deeply moving. In June 1969, he was finally exonerated when an inquiry ruled that it was slush on the runway, as Thain had always maintained, rather than ice on the aircraft’s wings that had caused the crash.

“The hounding of Jim Thain and his family is one of the many tragic tales within the wider Munich story and, researching the novel, I was shocked by the way in which he was treated by the British, by the press and sections of the public, with death threats not only to Thain himself but also to his wife and children,” explains Peace. “Although, ultimately, he succeeded in clearing his name, the ordeal must have contributed to his own death at just 54.”

Peace, who moved to Japan in 1994, has a brilliant gift for captivating 21st-century readers with novelised accounts of events we assume we know better than we do. His powerful quartet of Red Riding books grew from an obsession with crime and police corruption, using the Yorkshire Ripper as their basis and inspiration. His first post-quartet novel, GB84, explored the history and legacy of the miners’ strike. As a novelist interested in social documentation and estrangement, he has remained on the margins of the literary world and always taken on subjects that interest him personally. In his “Japanese novels”, including Tokyo Year Zero, real-life crime inspired a deep meditation on the state of the country he has made his home.

He’s always been interested in polyphonic structures, his novels invariably a cacophony of multiple voices and testimonies. That technique is evident again in Munichs. One contentious issue is the title, which is sometimes aimed as a poisonous insult at Manchester United supporters by abusive Leeds, Liverpool and Manchester City fans. “I was aware of it and I very much wanted to reclaim it,” Peace explains (as he does in an author’s note at the end of the book). “That might be rich coming from a Huddersfield fan, but one of the things that sickens me most about the modern game is tragedy chanting. And I wanted Munichs to contain many different voices, because I felt strongly that many people, some like my dad, who didn’t even support United, were caught up in the tragedy. It is ‘Munichs’ plural because it happened to so many different people. Until I did the research, I didn’t fully comprehend the extent to which it was a national disaster. But what Busby’s assistant Jimmy Murphy did with what was left of the club is one of the greatest sporting stories you will come across. I defy anyone to read this novel and ever use ‘Munichs’ as an insult again.”

The culmination of Busby’s revival was the club winning the 1968 European Cup, with a team that included George Best and Munich survivor Bobby Charlton. Yet following the hugely successful Alex Ferguson era, the club has entered an era of decline and mismanagement. Has the weight of the past somehow added to the club’s 21st-century existential crisis? “I don’t think it’s the Munich and Busby era so much as the Ferguson ‘Class of ’92’ legacy,” Peace replies. “It comes down to finding a character and personality big enough to write their own United story, in the way that Ferguson eventually did. Or in the way that Jürgen Klopp did at Liverpool, too.”

Certain points in the careers of certain modern managers would make great novels

Peace jokes that he was a “terrible” footballer himself (“more interested in comics from America than sport”) and says his worst spectator experience was seeing Huddersfield lose 10-1 at Manchester City. So, if a genie offered a straight choice, Huddersfield winning the Champions League or him winning the Nobel Prize for Literature, which would he pick? “That’s perhaps the easiest question I’ve ever been asked,” he replies. “Town winning the Champions League, of course. And, as my daughter just said, ‘much more realistic’ too.”

He seems drawn to major contemporary figures with something obstinate and unique in their psychological make-up (he has also toyed with writing about cricketer Geoffrey Boycott), and I wonder if any modern football managers have the personality to attract a similar study to Clough or Shankly? “In a different way, I do think certain points in the careers of certain modern managers would make great novels. For example: Ferguson’s difficult early years at United, or the rivalry between Guardiola and Mourinho when both were in Spain; and who could resist reading a novel about the rough magic weaved by Neil Warnock…? Seriously, though, the problem is that in the age of 24/7 rolling sports news and endless ‘banter podcasts’, there seems less mystery left in the game, and I think every story, football or not, needs a mystery, or at least to be asking a question.”

Football writing is often derided (sometimes fairly) but when it’s done expertly, as it is by Peace, the author can make sense of a bizarre tapestry of life: the intrigue, dishonesty, grief and suffering, as well as heartwarming aspects of courage, imagination and fortitude. It is little wonder that the potency of United’s story, and the link to his own late father, made him so keen to write Munichs. “Just think of the amazing way that the footballers Harry Gregg and Bill Foulkes were in that horrific crash and then had the character to get back playing so quickly,” he adds. “To me, the Munich air crash is one of the most incredible stories there’s ever been.”

‘Munichs’ by David Peace is published by Faber on 29 August, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments