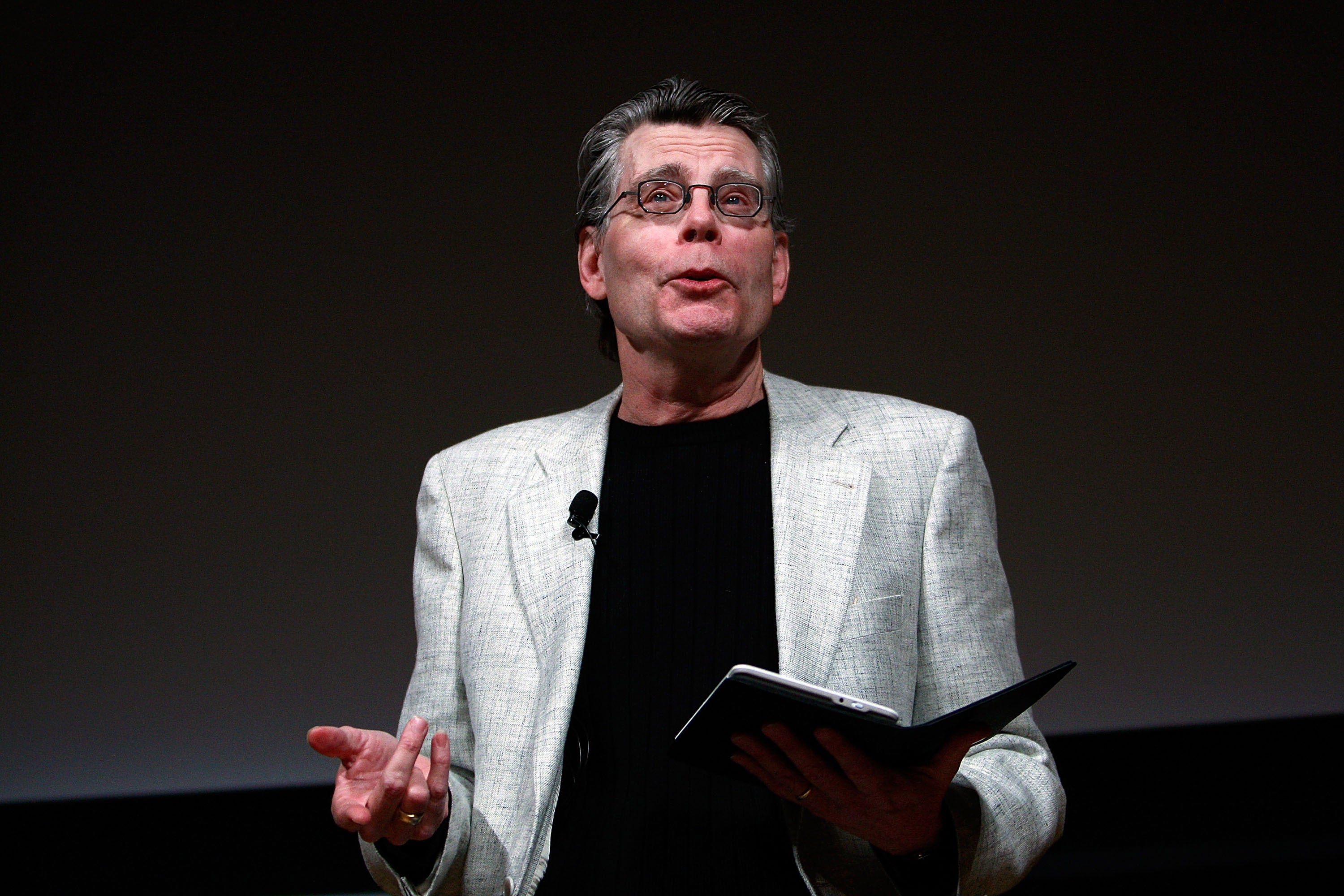

The gruesome genius of Stephen King

Master storyteller Stephen King has always written as if the end were nigh, says Robert McCrum. In ‘Holly’, a tale of Covid, cannibalism and red state America, one of his favourite protagonists returns – and is lavished with the kind of dialogue most mortal writers can only dream of crafting

When it comes to the four-wheeled page-turner, Stephen King is like a vintage car enthusiast, a Mr Toad. He adores the fine-tuned purr of the old-school novel, loves to lift the bonnet, show off its moving parts, and perve over the chassis. Racer or classic, ancient or modern, he cherishes them all, living for the thrill of the open road – the inimitable lure of the story. Ever since the publication in 2000 of On Writing, the justly-acclaimed memoir that followed his near-fatal collision with a van, King has never missed an opportunity to road-test his delight in the awesome potential of the popular novel.

This obsession goes way back. When young Steve first read Lord of The Flies, he reports that it grabbed him by the throat with “This is not just entertainment, this is a matter of life and death.” For as long as anyone can remember, King has been writing as if the end is nigh. Which, in King’s case, it usually is. As well as obsessing to the max, apparently in some last-chance saloon, King can often be found having the time of his life with his characters. He has the natural storyteller’s gift for conducting a love affair with a favourite protagonist in a way that’s not schlocky.

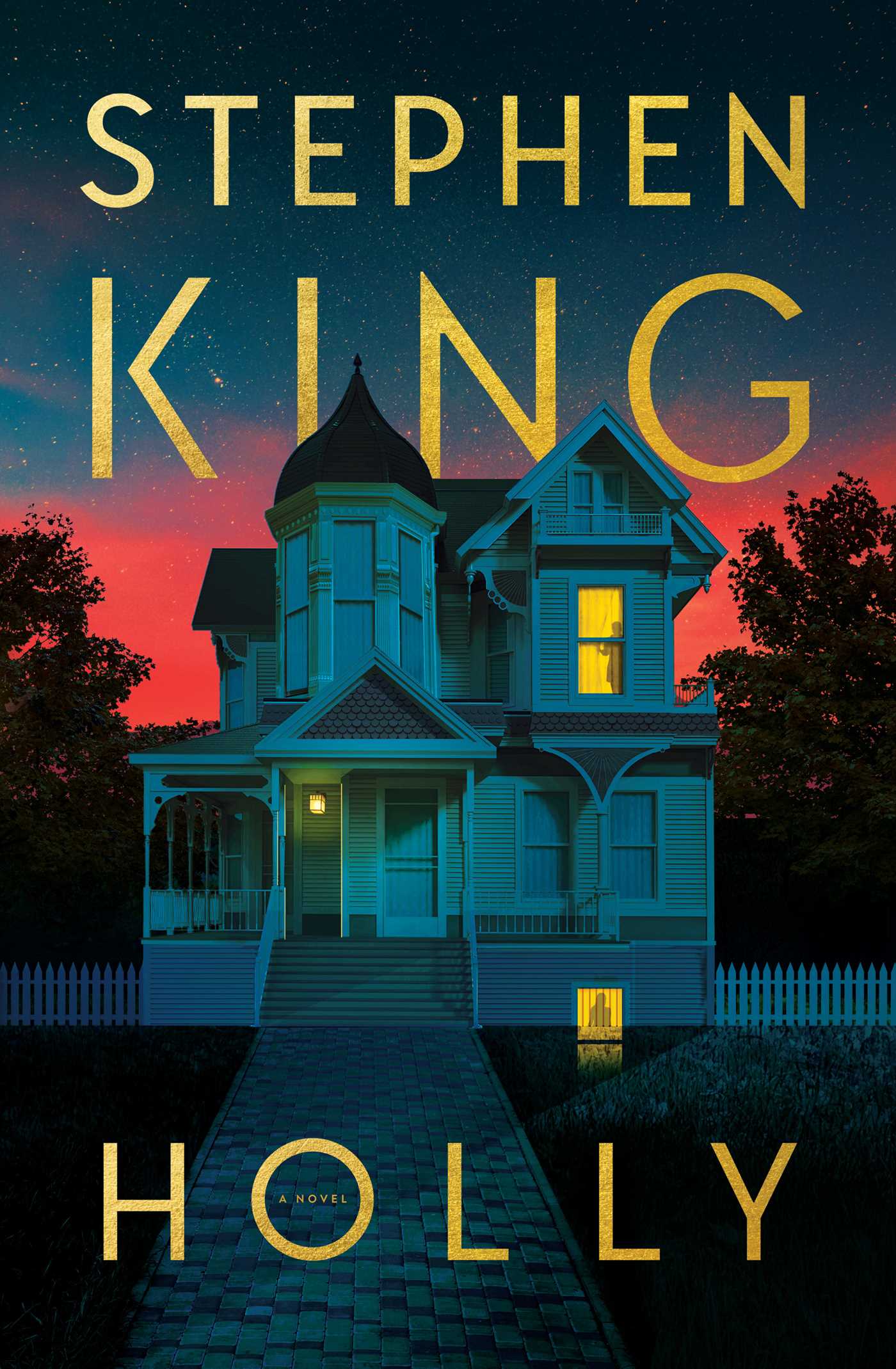

Holly, inspired by Covid, and written in a white heat from August 2021 to June 2022 is both a 400-page horror novel, and also a case study of King’s authorial psychology. In case you missed this, amid the visceral horror of his plot, he button-holes the reader in an author’s note, which confesses that “I’ve loved Holly from the first” – Ms Dibney made her debut as a walk-on part in Mr Mercedes (2014) – “and I wanted to be with her again.” King’s portrait of Holly is sympathetic, subtle and seductive. His ability to recruit his audience to the colours is just one of his best qualities as a compulsively entertaining artist.

Not that this guarantees Holly an easy ride. King’s credo that “there is no end to evil” never varies. He will run the weird gamut of his imagination to test her resilience. Her beloved mother has just died from Covid. Smothered in grief, this attractive, resourceful gumshoe from the detective agency Finders Keepers squeaks home to happily-ever-after by the skin of her teeth in a spine chiller that boasts a husband-and-wife team of psychotic serial killers, the Harrises, who are a) college professors, b) in their dotage and c) cannibals. En passant, let’s agree that only a master such as King could spin this grisly, far-fetched premise into a satisfying exercise in grand guignol.

We watch King’s heat-seeking mind lock onto Killer Old Folks, with this twist: he’s also cooking up a perverted campus sub-plot (Professor Emily Harris teaches in the English department) replete with Latin asides and crafty references to Ginsberg, Sylvia Plath, Ferlinghetti, Sharon Olds, James Dickey and the late Cormac McCarthy.

Holly takes us on a spin through the deranged years of Covid and the Trump disruption. It becomes a witty mash-up of creepy crime story, the way-we-live-now and vintage King-tastic horror. As he modestly puts it in his author’s note, “making s*** up is what I do best.”

Up to a point. King is a sleight-of-hand merchant who’s using popular entertainment to explore – through his vicious old cannibals – the decayed anatomy of red-state America today. Never mind the gruesome plot behind several mysterious disappearances from this un-named mid-western town, King is quietly eviscerating the hysteria of the MeToo years, the trauma of the Capitol riot, the hypocrisies of “woke”, and the heartbreak of the pandemic. He achieves this in two principal ways: through the perfect pitch of his dialogue, and a near-total absence of soapboxing.

King has a natural ear: most of Holly is sustained through dialogue. Not only is this brilliantly observed, it is lucid, complex, and sometimes very moving. Holly’s care-home meeting with one old geezer contains a perfect soundbite of stroke talk (“Oddy! All-all! Oore!”). This light touch combines with the narrator’s tact. He simply lets Holly’s insatiable curiosity about Bonnie Dahl, the missing campus “elf” who’s left a sinister farewell note (“I’ve had enough”), trigger a deep dive into an abyss of sadism, vengeance, and fathomless evil, all of which King normalises through his cunningly cosy narration.

With more than a nod to Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, King bundles the reader into his confidence as the omniscient narrator, establishing a tone of voice in which anything seems possible. He understands, better than almost any living writer, how to suspend disbelief. In the same breath, he also extracts gallows humour from the collision of Bonnie Dahl’s fateful rendezvous with the grisly geriatrics on Ridge Road.

King understands, better than almost any living writer, how to suspend disbelief

Something else is also at play in this meeting of horror and history, a conviction that animates Stephen King’s well-documented love of the novel that is braided into every page of On Writing. Good prose, King demonstrates, does not work in the way some writing schools pretend, by trying to crack some hidden code, master a witchy formula, or unearth the golden key to narrative magic. Fiction succeeds when it gets inside the reader’s head, and engages our secret hearts and minds. This is the only kind of work that lasts. Occasionally, in Holly, King – the vintage prose nut – breaks cover in his celebration of the writing life to confide some literary wisdom. “The only person unhappier than a writer whose expectations aren’t fulfilled,” declares the old poet Olivia Kingsbury, a delightfully eccentric character who plays a small but vital part in the resolution of the plot, “is one whose dreams come true.”

King is now so acclaimed that perhaps his dreams have come true. Certainly, he may have become too grand to be properly edited. On my reading, Holly is about 10 per cent too long, especially in the closing 150 pages. Still, he’s under no illusions, and tells it how it is: “The work matters. Nothing else. Not prizes. Not being published. Not being rich, famous, or both. Only the work.” Here’s a writer who’s still at the wheel.

‘Holly’ is published by Hodder & Stoughton on 5 September, £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments