The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Book of a lifetime: Joe Gould’s Secret by Joseph Mitchell

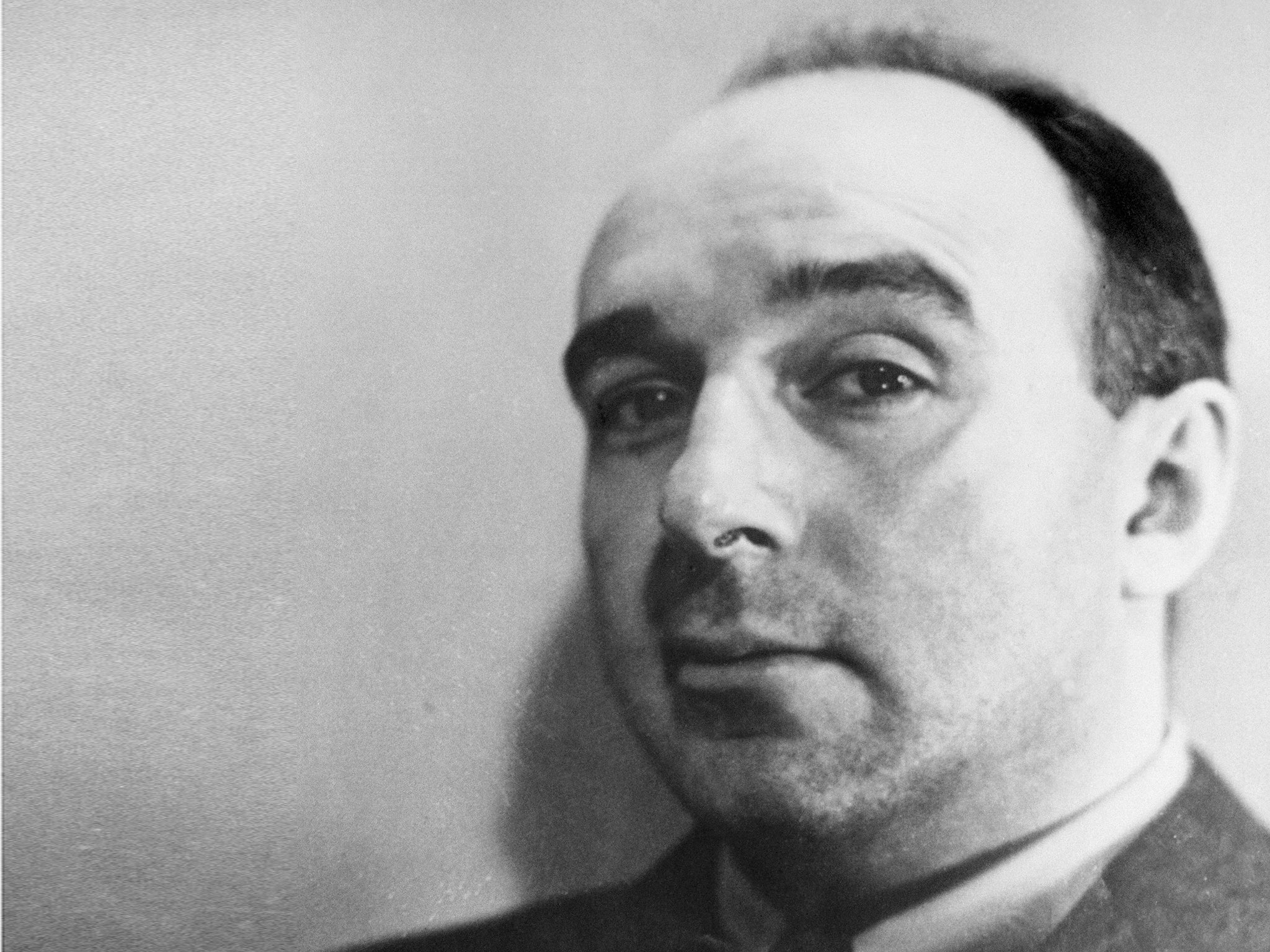

From The Independent archive: Nicci French on an eerie masterpiece of profile writing about a solitary nocturnal wanderer – by the greatest non-fiction writer ‘The New Yorker’ has ever seen

Joseph Mitchell isn’t much talked of nowadays but, even in a group that included Truman Capote, John Hersey and Rachel Carson, he was probably the greatest non-fiction writer in The New Yorker’s history. He had been born in the Deep South but virtually his whole professional career was spent in New York City, with a matchless gift for listening to gangsters and cops, prize-fighters and longshoremen, barmen and Gypsies.

In 1932 Mitchell got to know Joe Gould, who was a Greenwich Village legend, a vagrant, a talker, a writer; some said a genius. He was constantly working on an epic book called An Oral History of our Time. Mitchell himself was an obsessive reader of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce, which he said he had read at least half a dozen times. It may be that for Mitchell, Gould’s endlessly expanding, never-seen work came to represent the possibility of a Manhattan low-life version of Joyce’s obsessive, crazy masterpiece. It was a ghostly counterpart to Mitchell’s own career, spent capturing the talk of apparently ordinary people, shaping it, giving it form and permanence.

In 1942, Mitchell suggested profiling him for The New Yorker: “I remember telling the editor that I thought Gould was a perfect example of a type of eccentric widespread in New York City, the solitary nocturnal wanderer”.

Over the years, Mitchell became a Boswell to Gould’s drunken, deranged Dr Johnson: “I listened to him when he was sober and I listened to him when he was drunk. I listened to him when he was cast down and meek – when, as he used to say, he felt so low he had to reach up to touch bottom – and I listened to him when he was in moods of incoherent exaltation.”

The odd thing is that Mitchell never made particular claims about Gould’s talent: “Gould’s writing was very much like his conversation; it was a little stiff and stilted and mostly rather dull, but enlivened now and then by a surprising observation or bit of information or by sarcasm or malice or nonsense.”

After the profile appeared, Mitchell got more entangled in Gould’s affairs, his struggles for money, accommodation and getting his Oral History published. Most of it ended in disaster and when Gould died in 1957, not a single page of the Oral History was found.

Mitchell embarked on a second part of his profile, more revealing not just about Mitchell’s own role in Gould’s affairs but about the eerie connections with Mitchell’s own writing life. The short profile took him five years to write.

After it appeared, in 1964, Mitchell never published another word, though he remained a staff writer on the magazine until he died in 1996. Mitchell’s unforgettable account of Gould’s nightmarish writer’s block had been, in complicated ways, a self-portrait.

Why does the book mean so much to us? It’s a masterpiece, of course, but more than that it shows that there is no such thing as being a simple observer. There is no such thing as a detective who solves a crime and moves on untouched, a psychoanalyst untainted by her patient. What was it Nietzsche said? “If you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments