Book of a lifetime: Beowulf

From The Independent archive: Justin Hill delights in how each new translation resurrects the Old English into modern and keeps this ancient poem fresh and fascinating for generations to come

So in 1983 I was 12, and my parents took me to see an actor who had been in Star Wars, performing in York Theatre Royal. I felt a little self-conscious as the lights went down, a harpist plucked out a strange tune, and then a single man, in fur and cloak, appeared under a lone spotlight. “Hear,” he said, “Listen!” So Julian Glover began his rendition of Beowulf.

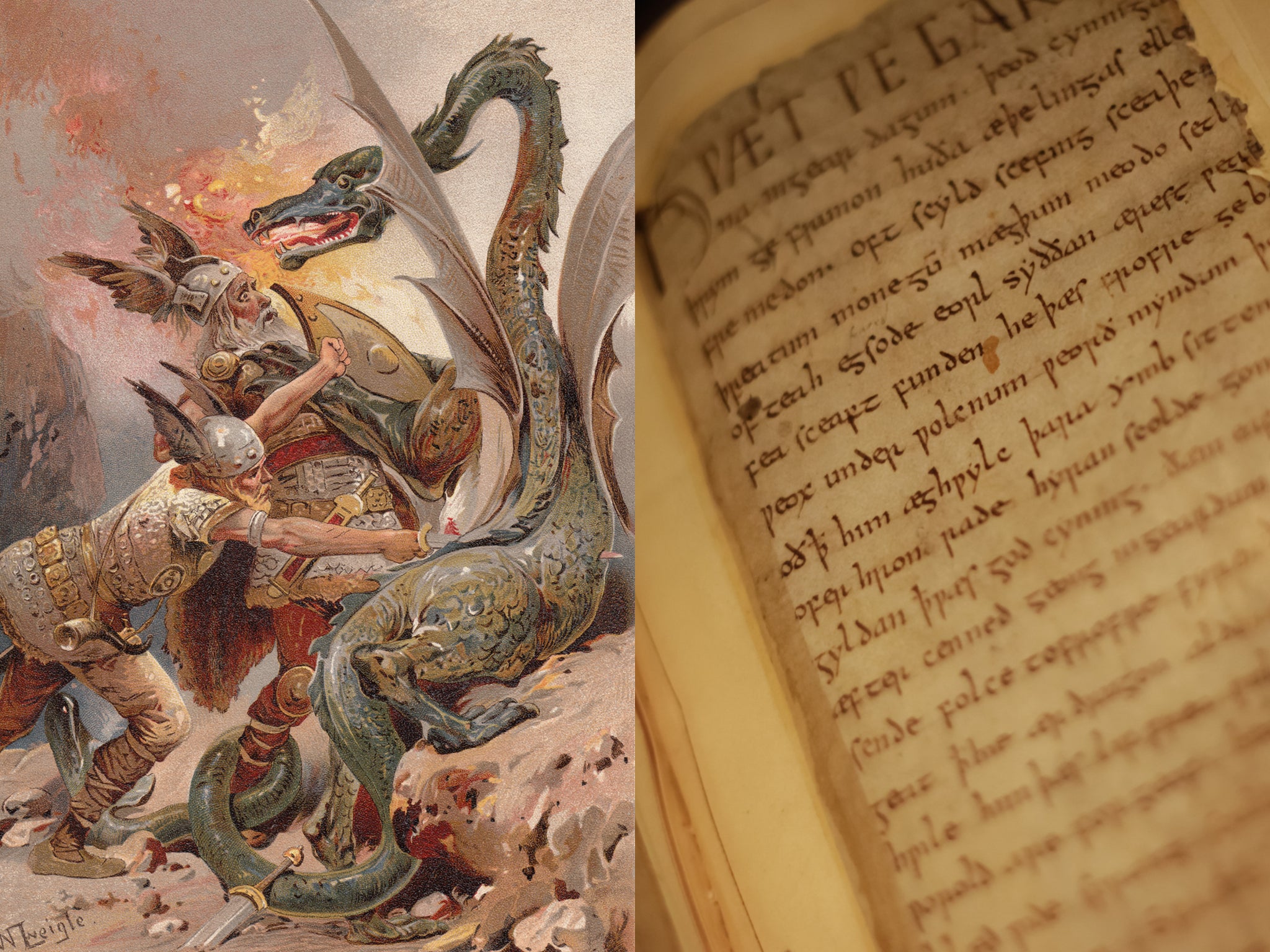

The tale describes a battle with three monsters: Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and finally, when Beowulf is an old man, a hoard-guarding dragon. I was rapt. The tale spoke to me of dark winters, and late summer evenings, alone and walking the dog between the black thickets – the dark wild landscape as terrifying as it had ever been.

Glover’s version conjured all the light and dark and humour of the poem. We could have been with Beowulf in the Danish hall, fighting the dragon, or sitting close by as he breathed his last. At the intermission, stout ladies walked down the aisles to sell ice cream, but I bought a cassette of the performance, and for years after, listened to that tape and soaked it deep.

I was lucky to come to it, not as a book, or a passage in Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer, but as a story recounted to an audience. The story as it had been meant to be received: in a hall or round a fireside. And I did not stray from Glover’s version (which combined versions by Michael Alexander and Edwin Morgan) until Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf, which riffed on the Old English, re-shaped it, and delighted me with its differences.

So where I knew “A foam-throated seafarer on the ocean’s swell”, Heaney had “A lapped prow loping over currents”, which brought to mind packs of longships hunting along the coastline. Where Glover described how God “loaded the acres of the world with jewelwork/Of branch and leaf, bringing then to life/Each kind of creature that moves and breathes”, Heaney had “[He] filled the broad lap of the world/with branches and leaves, and quickened life/in every other thing that moved.”

Each translator resurrects the Old English into modern and this keeps this ancient poem fresh and fascinating. Now, at last, I’m coming to Beowulf in the original Old English, and it continues to surprise and delight as I rephrase it into my English.

But ultimately the magic of any much-loved piece of literature lies perhaps in the moment we first discovered it. Beowulf seemed immediate and relevant to the 12-year-old me in a way that much else I had read did not. When Beowulf lay sleepless in Heorot, I understood the fear of the dark. When he battled Grendel’s mother, I felt the terror when his sword broke on the giantess’s skull. When he set out to face the dragon, old and weary and certain of his own death, I understood his mood as he tried to cheer his followers. And when he dies, Beowulf has much to both regret and be content for, but most importantly he is well-remembered among his people. The best immortality, I think.

Or – as the old poets said – is it that when all else fails, “Word alone endures”? A fitting message, perhaps, from one writer to another.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments