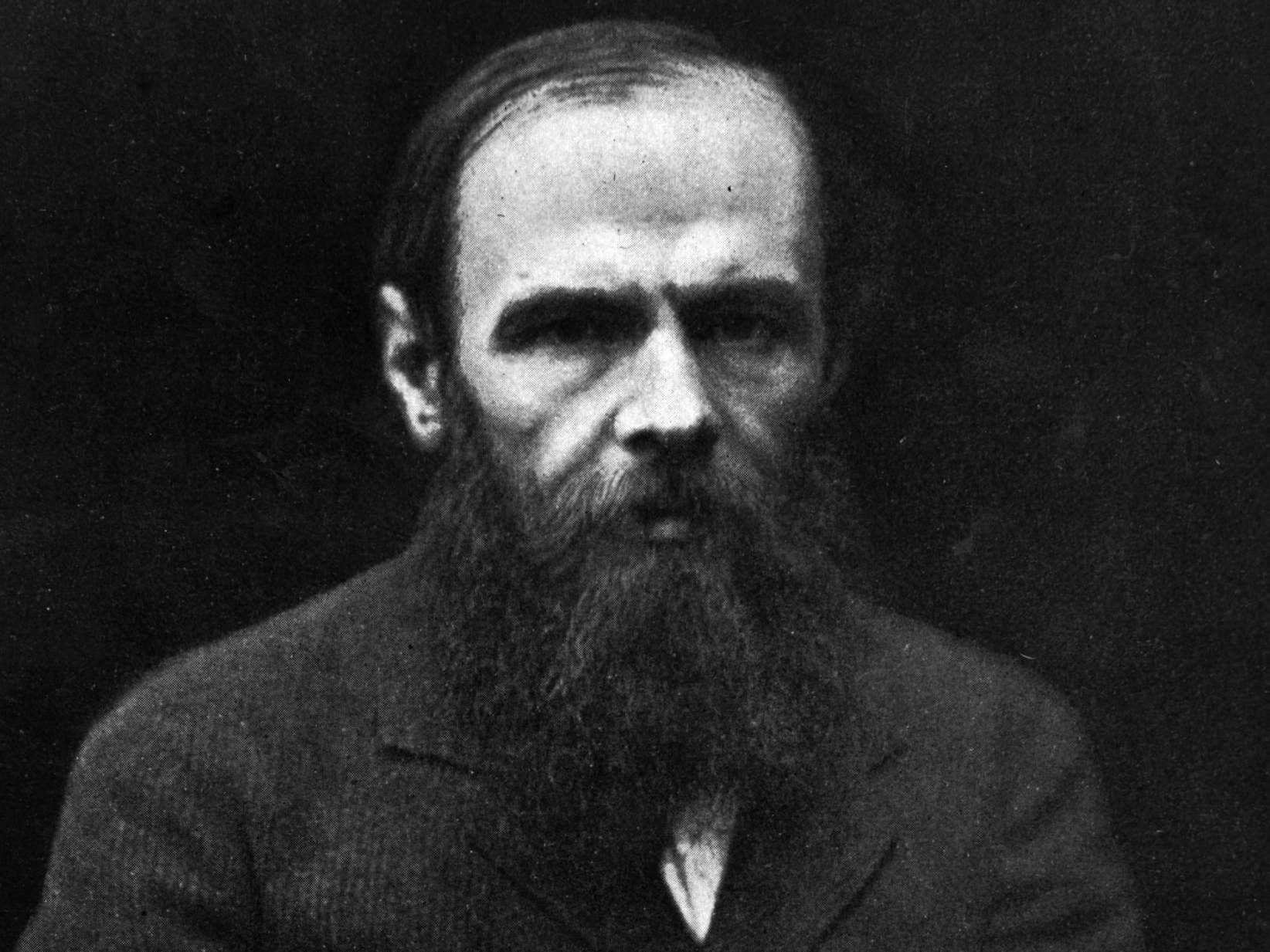

Book of a lifetime: The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

From The Independent archive: Richard T Kelly reflects on the Russian master’s ragged portrait of religion, madness and parricide

The Brothers Karamazov has been my friend since I was 18 and first read David Magarshack’s 1958 translation. Then, as now, it struck me as the grandest, richest and strangest of Dostoevsky’s four “big” novels.

True, bookish teenagers can be overly partial to “sensitive murderers and soulful prostitutes” (Nabokov’s high-nosed dismissal of Dostoevsky), and there’s no denying the delirious melodrama in these books. But having lived with Karamazov for 20-odd years, I am certain Kafka judged it correctly in arguing that Dostoevsky’s characters are not all lunatics – just “incidentally mad”, like the rest of us.

Karamazov is a tale of parricide: three disparate siblings with a kindred urge to do in their dissolute father. Some argue that to create those brothers Dostoevsky “merely” split himself three ways. I’d say that the point is that he contained sufficient multitudes to do so.

In my youth I identified with Brother Ivan, the brooding atheist. These days I feel closer to Dmitri, with his drives, frustrations and tempers. I’m rarely stirred by the religious novice Alyosha, but then nor was Dostoevsky. Ivan’s radical doubt – indeed his heretical faith in “the force of the Karamazov baseness” – is what lays coals on the novel’s fire.

Dostoevsky’s storytelling can be ragged: in his expansive structures and sudden turns he can sometimes remind you of Raymond Chandler’s advice that the “stuck” writer should just have a man walk in with a gun. But his indisputable claim on greatness is as a maker of “scenes” charged by all kinds of fierce conflict: hence George Steiner’s hailing of him as “one of the major dramatic tempers after Shakespeare”.

My second favourite scene in Karamazov – classic Dostoevsky in its idea of redemption through suffering – is Dmitri’s “good dream” after he has fallen asleep, exhausted, in the courtroom where he stands accused of murder. One heart-wrenching vision of unconditional love inspires Dmitri’s confession to a crime he didn’t commit. He has decided he is a sinner, and “such men as I need a blow, a blow of fate, to catch them as though with a lasso and bind them by a force from without”.

Arguably this is madness; also great pathos. The scene I love best, though, is Ivan’s hallucinated encounter with a shabby aristocratic devil who affably refutes his complex atheism. This might indeed be my favourite passage in literature, one that I stole and re-worked in my novels Crusaders and The Possessions of Doctor Forrest.

I confess this freely (I want to be found out), and well-read readers might think it an annoying pseudery. But in my teens, I first heard of Dostoevsky through a minor American novelist whose own name I’ve long forgotten – still, I owe that guy, and I believe in passing on the good word.

To me this is what Christians mean by “stewardship”, and as such I pray The Master (by which I mean Dostoevsky) might approve.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments