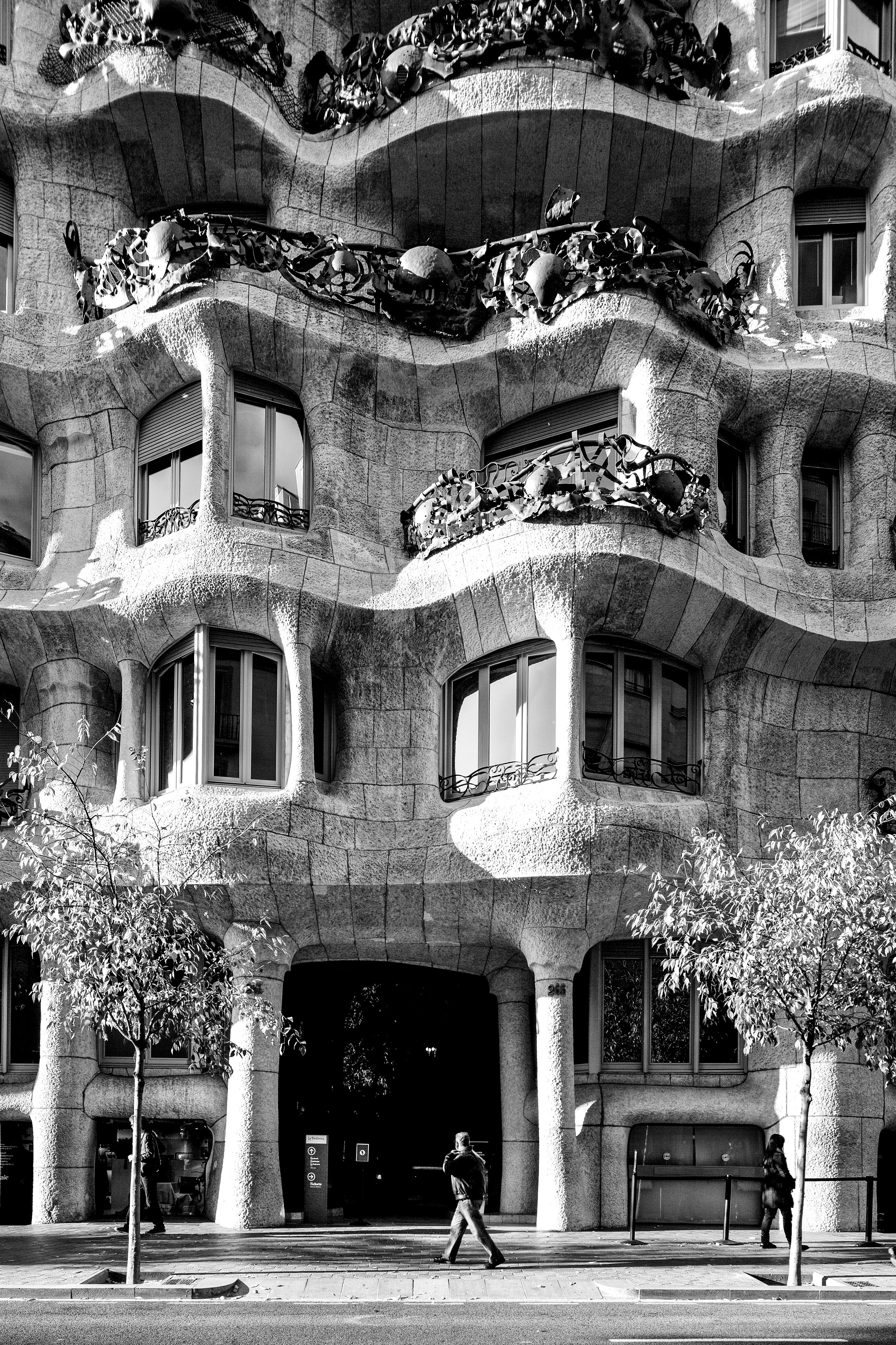

‘Gaudí’s Casa Milà is a joyous festival of curves – it’s almost as if the building is breathing’

For 30 years Thomas Heatherwick has been one of the world’s most imaginative designers: his bold, beautiful creations are full of originality, inventiveness and humanity. In the first of a major three-part serial of his new book, ‘Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Building Our World’, he reveals how an encounter with a Barcelona apartment block stunned him as a young man – and sparked his vision of a world full of brilliant, soulful buildings

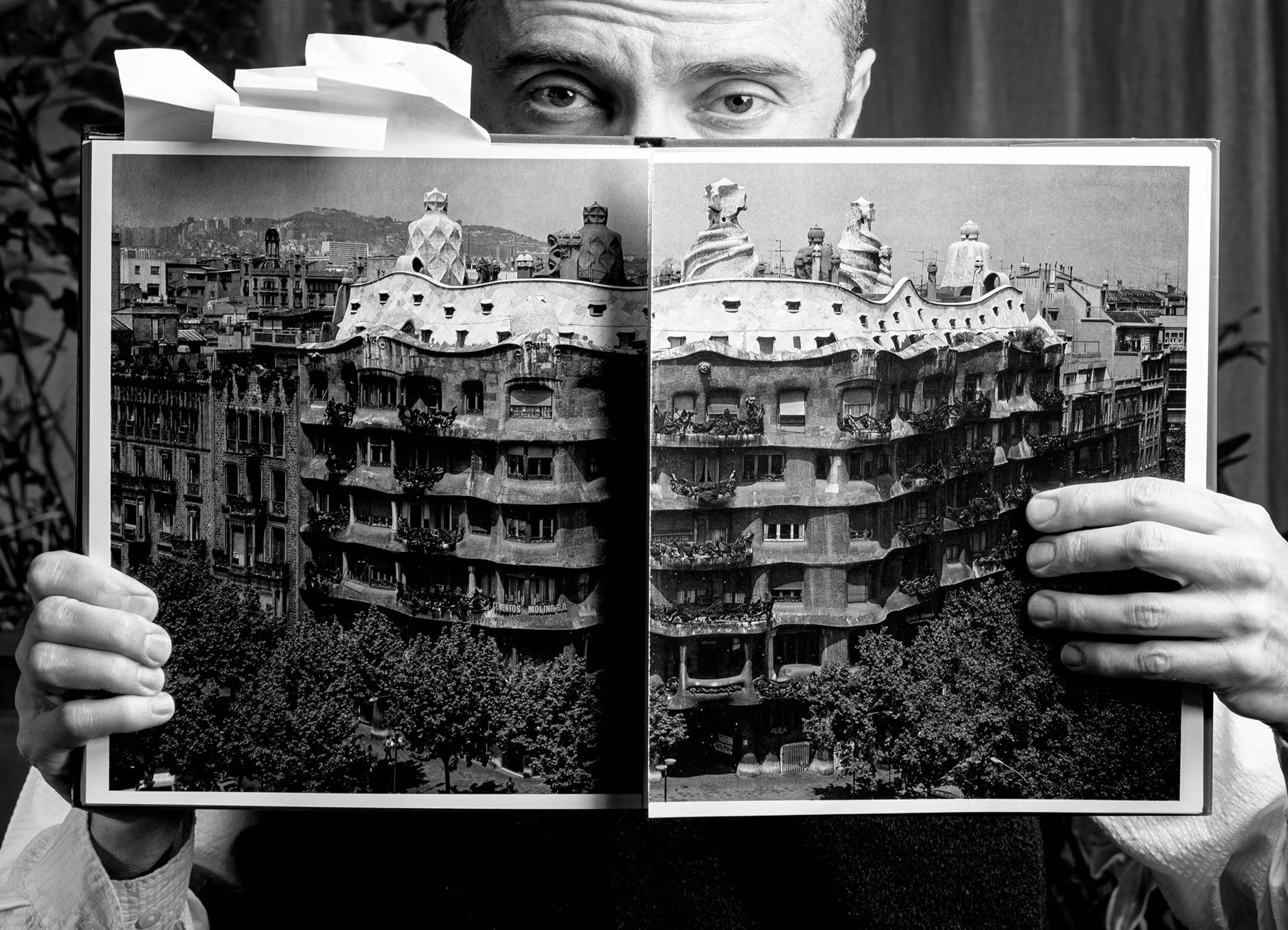

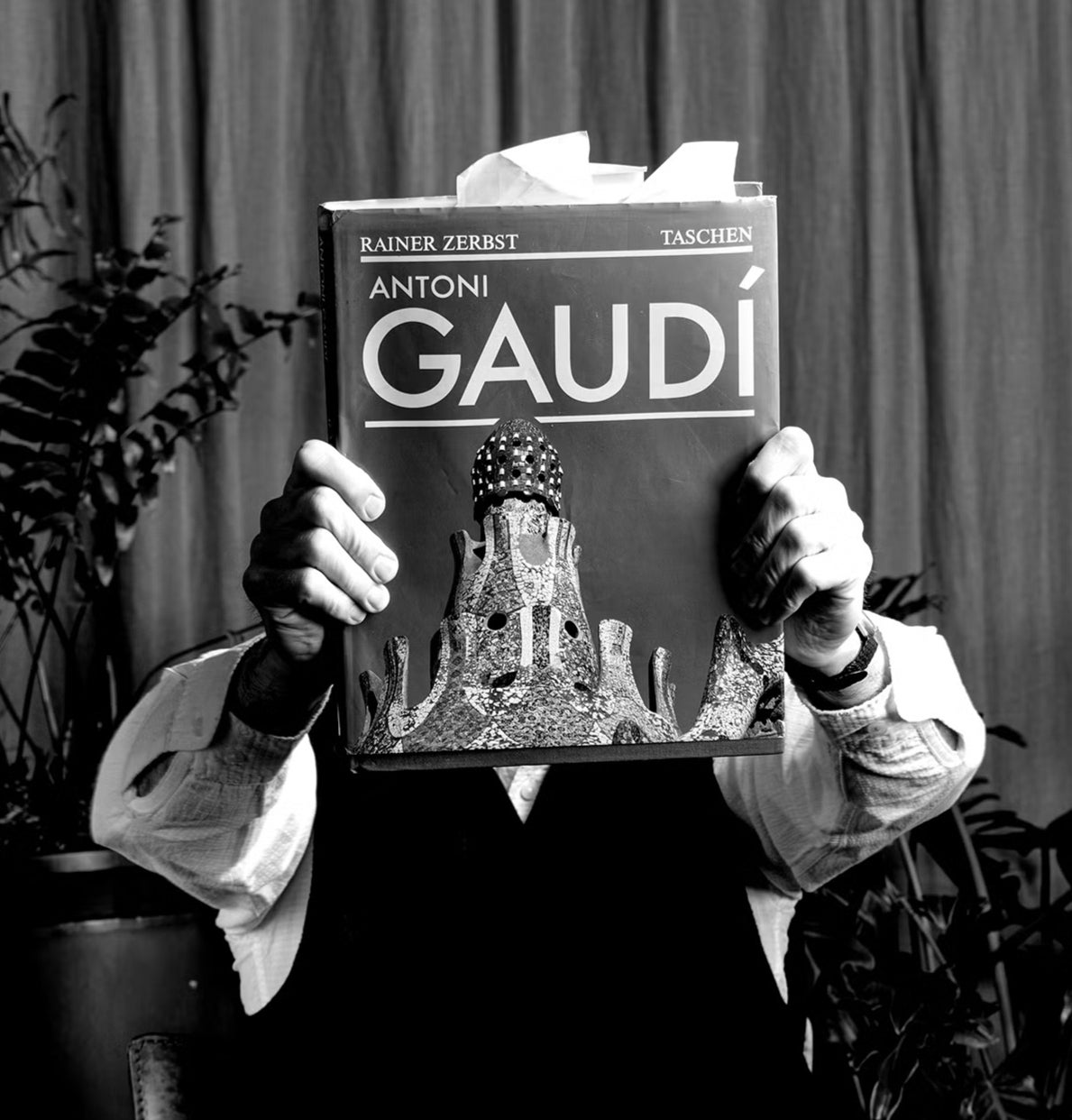

The best £6.99 I ever spent was on a January afternoon in Brighton in 1989, when I saw something in a student book sale that grabbed my attention. I’d made the journey for an open day at the University of Sussex, to have a look at the Three-Dimensional Design course. Ever since I was small, I’d been fascinated by inventions and new ideas and the design of objects. Now that I was 18 years old, I was working towards a BTEC National Diploma in Art and Design at Kingsway Princeton College in London, studying drawing, painting, sculpture, fashion, textiles and three-dimensional design. Years earlier, I’d given up on the idea of pursuing building design, because what I’d seen of that world known as “architecture” felt cold, impenetrable and uninspiring. But then I wandered into the student union sale, picked up this book, opened it at a random page and a switch in my brain flicked on.

There I saw photographs of a large, dirty building on the corner of a street in central Barcelona. The building was called Casa Milà; it was unlike anything I’d ever seen in my life. It simultaneously had the qualities of an incredible raw, carved stone sculpture and a contemporary apartment block.

I was stunned. I had no idea that buildings like this existed.

I had no idea that such buildings could exist.

If buildings could look like this, why weren’t there more of them?

If buildings could look like this, what else could they look like?

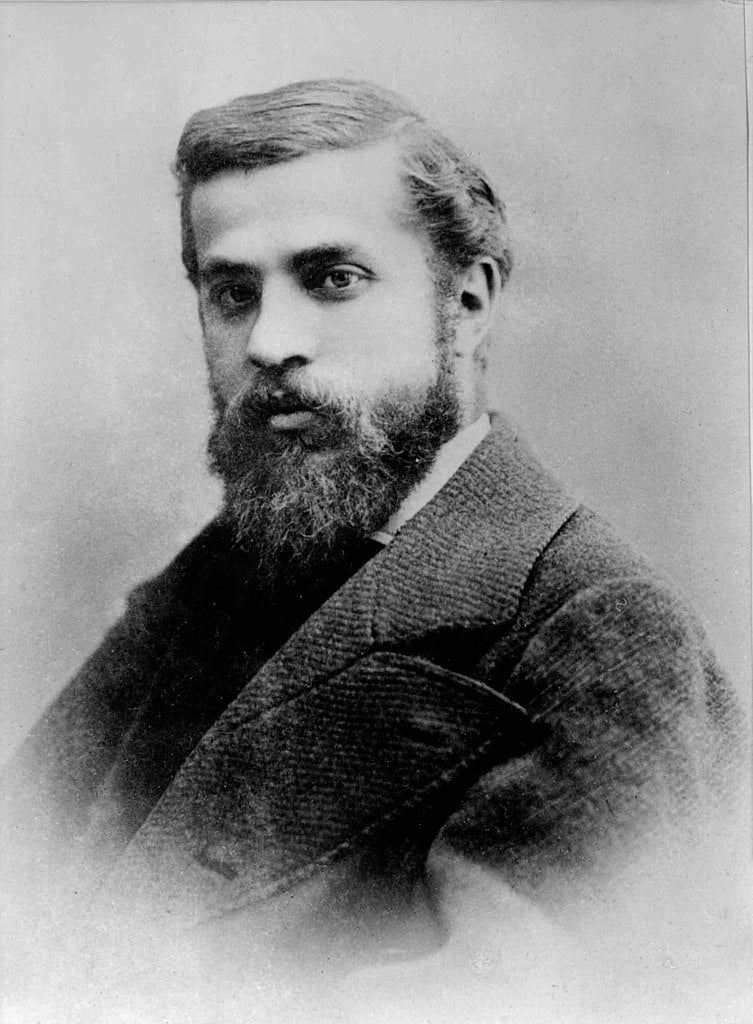

Thirty-three years later, I travel to Barcelona to see Casa Milà. I fly in from a meeting in Munich and, as I queue to catch my plane, I hear one of the passengers making a quick call. I don’t speak fluent German, and can’t fully make out what she’s saying. But I can clearly understand one word – the name of the man who made the building I’m here to see. She keeps repeating it, every few moments: “Gaudí... Gaudí... Gaudí...”

I’ve seen Casa Milà in real life a number of times before this trip. But today I feel I’m able to grasp its genius much more clearly. I lead a busy studio in King’s Cross, London, that’s designed bridges, furniture, sculpture, Christmas cards, a car, a boat, New York City’s “Little Island” park, London’s red Routemaster buses, and the cauldron in the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Games. But we mainly design buildings. So I know about the forces of money, time, regulations and rules and politics, as well as all the important people who can tell you “no” at any moment. I also understand the never-ending pressure to water down a creative vision and how incredibly hard it is to make any new building whatsoever, let alone one that is special.

I remember a recent conversation in London with a friendly architect – when I showed them that my studio and I were proposing to place a slight curve above an otherwise rectangular window, they commented: “Wow, you’re brave.” That comment was a spooky clue to me that there was something badly wrong in the world of building design. As I approach Casa Milà now, I see before me the ultimate dismissal of that scared perspective – a masterpiece by the man who apparently once said: “The straight line belongs to men, the curved one to God.”

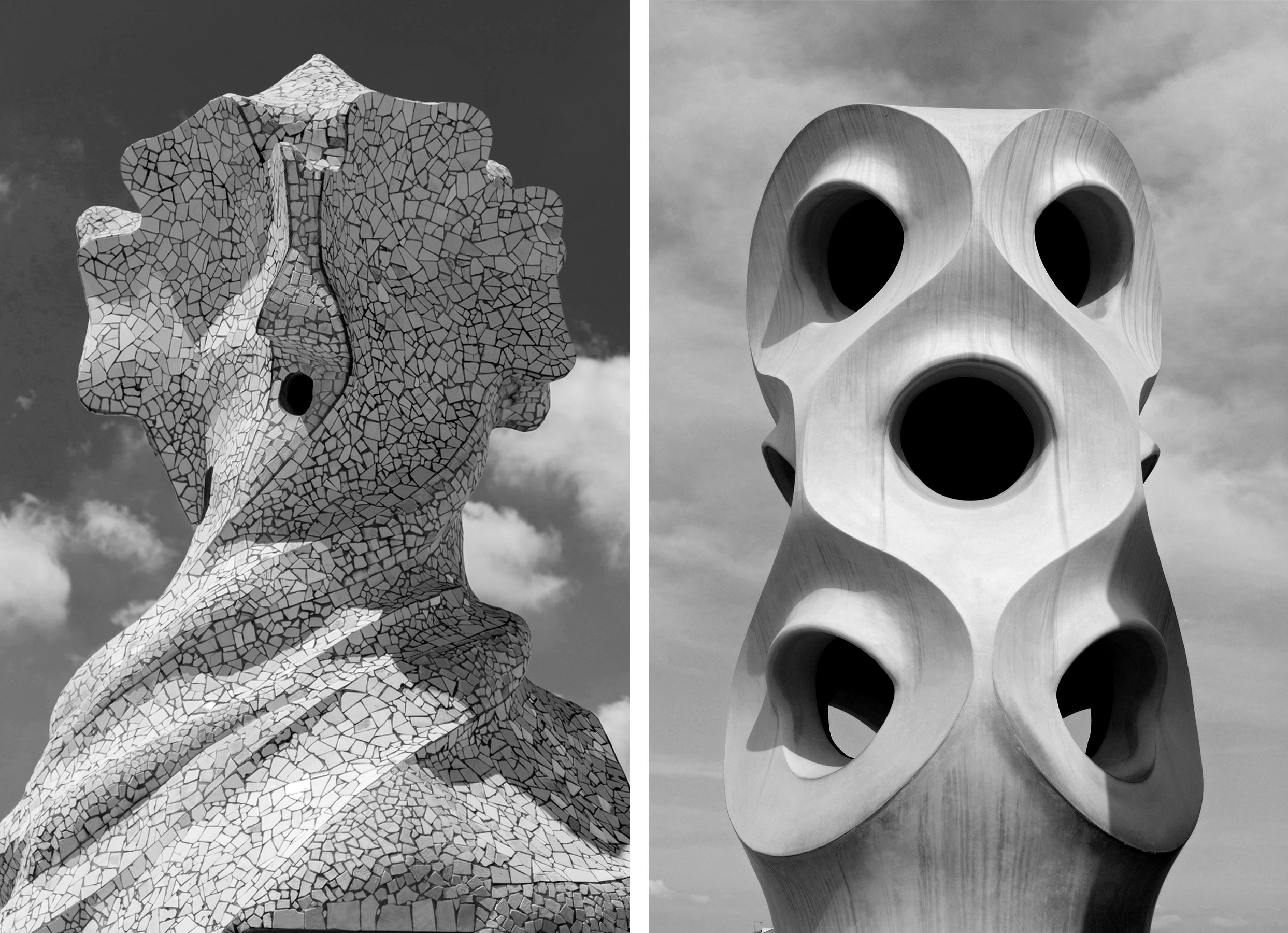

Casa Milà is an unashamed festival of curves. The windows of its sixteen apartments look like they have been energetically carved out of a limestone cliff face. It is the opposite of flat. The front of the nine-storey building undulates amazingly in the light, dancing in space – in and out and up and down – almost as if the building itself is breathing.

In front of the stone are balconies of wrought iron that writhe asymmetrically in abstract shapes, like giant seaweed pieces that protect you from falling. And on the roof, twisting, highly artistic chimneys and ventilation stacks sprout upwards from a large terrace. After it was completed in 1912, its critics gave Casa Milà the nickname La Pedrera, or “The Quarry”, because it had the appearance of having been cut out directly from the stone in the ground.

Then, as now, Gaudí’s building was a sensation. The news of Casa Milà’s construction was reported in popular magazines of the time such as Ilustracio Catalana. But as celebrated as he was, even Gaudí got in trouble with the local authorities. Casa Milà broke several city building codes: it was taller than was permitted, and its pillars intruded too deeply into the pavement.

When Gaudí was told a visit by the building inspector had gone badly, he threatened that if he was forced to cut his pillars back, a plaque was to be attached, saying: “The section of the column that is missing was cut on the orders of the City Council.” In the end the pillars were left alone, but a fine of 100,000 pesetas was demanded: a significant sum, just a little less than Gaudí’s entire105,000-peseta fee for designing the building.

As I stand on the other side of the busy crossroads, it’s astonishing to think that while Gaudí and his clients were making a priceless gift to the city, the authorities were imposing a big fine on him. Even though this building was made to provide high-end apartments for wealthy people, I believe it is a gift. Casa Milà is an act of spectacular generosity. A selfish building cares only about its ability to make profit for its owners, and disregards everyone else. But Casa Milà reaches out to every one of us who pass it every day, wanting to fill us up with awe and break us out in smiles. Even forgetting the riches that this and other Gaudí buildings have gifted their nations as tourist attractions, the sheer joy that Casa Mila has given to hundreds of millions of everyday passers-by is unquantifiable.

Waiting at the pedestrian crossing, I reflect on what makes Casa Milà so visually successful. Partly it’s a result of its gorgeously distinctive combination of repetition and complexity.

Humans seem to be drawn to repetition: I think of the columns of a Greek temple, or the repeating patterns in the timber beams of a Tudor house, or the repetitive windows in a British Georgian crescent of terraced houses. We naturally appreciate order, symmetry and patterns in artworks and objects.

But we don’t like too much repetition. Just enough allows us to feel oriented and reassured; too much feels oppressively boring and tyrannical.

Humans also like complexity. As animals we’re naturally curious, intelligent and easily bored. We gravitate to interesting things that invite us to look more in order to understand them. But complexity without any order or repetition can feel alarming and chaotic.

What we like is just the right combination of repetition and complexity. Not one, nor the other – but both, complementing one another. This is surely related to our evolution in natural environments. If you think of a forest of trees or ripples on a lake or the markings on a butterfly’s wings, you’ll be picturing a play of repetition and complexity. These are images that probably inspire feelings of quiet elation in almost everyone.

If you want to design a building that will be attractive to most human beings, repetition and complexity are vital tools. These forces can act as opposites, but they need each other. And when the balance of their aesthetic tension is right, it’s possible to make works that most people will find astoundingly beautiful.

Outside of architecture, other art forms like music and storytelling also play with repetition and complexity. The rhythm of a drum, a verse and a chorus are all patterns that can repeat in a song, but complexity is frequently then layered on top of these elements, using string instruments, lyrics, and shifts in tempo and emotional intensity. The difference between a Beatles song like “Yellow Submarine” and a prelude by the classical composer Shostakovich is that one leans more towards repetition and the other towards complexity. They’re at opposite ends of the spectrum, but they use the same essential tools. Likewise, when we read a captivating novel, or watch the latest thriller, we can sense an archetypal pattern in the story: the drama goes predictably up and down and up and down until the inevitable finale. We know it’s going to happen, but if we’re not bored, it’s because the writer has added enough complexity to the ancient pattern to keep us interested.

Like a beautiful song or an absorbing novel, Casa Milà has a predictable pattern: horizontal floors, vertical columns, a grid of windows, curves of limestone. But it’s also incredibly complex. It’s simply not possible to understand Casa Milà at a glance, as you can with so many modern buildings. It demands that you give it a second look – and then a third and then a fourth, and then you’re craning your neck and squinting at it, grinning, trying to take it all in. It feels like a joyous three-dimensional puzzle that your brain is trying to solve.

As I cross the road and walk towards the building, I note its size is perfect too. If the same windows and balconies were repeated one floor higher, or were stretched and replicated further along the street, it would become too repetitive, and the balance and magic would crumble. As I step onto the pavement immediately in front of Casa Milà, I see the craftsmanship that’s embedded into every part of it. The early part of my career was spent understanding how to make things, so I know what it’s like to create objects by carving wood, chiselling stone and hammering big bits of hot steel. The ironwork on the balconies is mind-bendingly contorted and free-flowing, and from my own experience of beating iron on an anvil I can imagine the impossibility of trying to heat it and twist it and hammer it, let alone lift it. And as I look up, I can see that the ironwork is even doing something different on each of the balconies. There it is again: repetition and complexity, captured and immortalised in iron.

The stone face of the building has craftsmanship visible on its surface too. Even though it looks smooth from a distance, its creators didn’t spend lots of extra money polishing away the chisel marks to make it smooth up close.

Instead it is unapologetically raw, and the tiny randomised chipping marks add yet another layer of complexity that reminds us that this is the work of human hands. It’s not embarrassed to be raw and hacked. The way the light catches each one of those thousands of violent human-made notches changes with the weather and the arc of the sun, so the surface never looks the same from one hour to the next.

What I cherish most about Casa Milà is that it is so three-dimensional; the opposite of all the flat two-dimensional modern buildings we’ve got used to experiencing. Standing by it at street level, it flexes in and out over the pavement. With its beautifully gradual transitions between areas of light and shadow, it feels spookily as if – just by looking at it – I am touching its surface.

Thirty-three years after I saw it in a book that still sits – tatty and flapping with Post-its – on a shelf in my studio, Casa Milà has been cleaned of the soot that coated it when I first visited. It looks better than ever. Part of what excited me all that time ago was that this wasn’t an ancient castle or a royal palace from a distant era. This was a modern building that had been built for the age of the machine. It had lifts that carried its residents between floors and a back entrance that led to an underground car park. It showed me it was possible for modern buildings to be as beautiful and interesting as any work of art.

As a young man, on seeing that picture of Casa Milà, what I fell in love with wasn’t one building, but the potential of all buildings. Before that day in Brighton, I’d always seen the built world as fixed. Old buildings were almost always fascinating, but new ones were almost always mysteriously dull and monotonous. Buildings looked like what they looked like and that was just how things were. But Casa Milà opened up a crack in that fixed reality. Through that crack I caught a glimpse of the world as it might be.

TOMORROW: How the cult of boring took over the world – part two of our exclusive serial continues

Extracted from ‘Humanise: A Maker’s Guide to Building Our World’ by Thomas Heatherwick, published by Viking on 19 October at £15.99. © Thomas Heatherwick 2023

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments