Why we’re obsessed with building cities in the sky – from medieval Bologna to modern-day Manchester

Whether it’s the opening of Vegas’s tallest hotel, or the announcement of a new tower in the North, highrise design is back. But, asks Jonathan Glancey, what does the trend really tell us about how we live now and what we value as important?

Pisa-like, Garisenda Tower in Bologna, built around 1100 for a family of Ghibelline money changers, has been leaning for a very long while. Dante made a passing reference to it in Inferno, written in the second decade of the 14th century: “As when one sees the tower called Garisenda from underneath its leaning side, and then a cloud passes over and it seems to lean the more.”

Since October, the Garisenda Tower has been cordoned off. The city council fears it has finally leant too far and may well be on the point of collapse. Because it rises from the heart of the old city with buildings all around, not least the equally venerable and even taller Asinelli Tower, its fall could be catastrophic. No one, though it seems, wants the tower to go. Plans are afoot to shore it up in a long and costly renovation project. Bologna – La Turrita, the city of towers – is fond of its 20 or so remaining medieval “skyscrapers” of which in Dante’s day it boasted as many as 80 and perhaps even 100. The Bologna of 800 years ago might be seen as a medieval Manhattan or, should I say, Manchester.

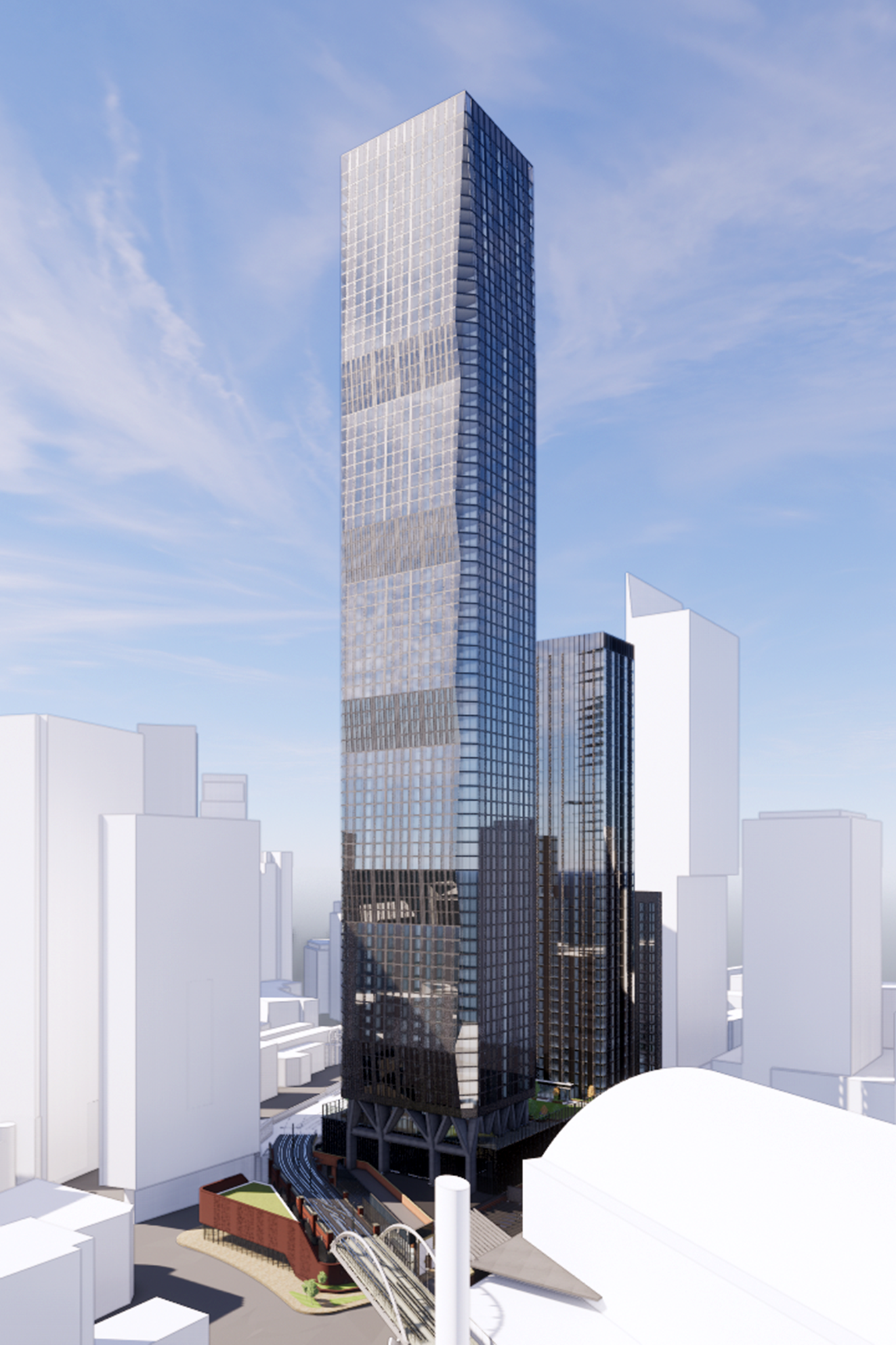

This month, plans were announced for Manchester’s tallest tower yet, a 76-storey, 750ft block of flats designed by SimpsonHaugh architects for Salboy, a local developer. Salboy describes the tower as an “exclusive residential development combining Manchester’s industrious past with decadent, modern city living.” However the decadence of modern Mancunians is measured, the city currently boasts 20 new 330ft towers with a further dozen about to sprout. As prickly as a hedgehog, Manchester’s new skyline is fast becoming as vertiginous as that of tower-crazed London or medieval Bologna.

Whatever next? Perhaps the city should invest, as Las Vegas has, in a hotel as tall as the future Salboy tower. The 67-storey Fontainebleau has opened in time for Christmas in Vegas, all 3,644 rooms and 36 bars and restaurants of it, and Elvis-only-knows how many gaming tables and slot machines. Tallest habitable building in the desert city. Way to go. We do, after all, tend to follow US trends whether in high-rise design or popular entertainment, or both together as with the sock-it-to-me 737ft Fontainebleau.

The impulse to build high in cities has long been strong. Considerations of land use aside – reach for the sky if land is limited – tall buildings are a way of shouting from the rooftops Jimmy Cagney-style. “Made it Ma, top of the world!” If the Ghibellines climbed so high, you could bet your bottom florin that the Guelphs would go higher. The same is true today as canny developers with the blessing of cowed, cash-strapped or asinine city councils, and to the applause of zealous neophytes, cry “higher, higher!”

What has changed significantly over the centuries is the purpose of city towers. Those of Bologna or San Gimignano – 72 towers up to 230ft in the years before the Black Death ravaged these cities – appear to have been built to express the power and wealth of sparring families. If they doubled up as defendable lookouts, it is hard to see quite what their owners saw from them other than the serried bricks of rival towers. As these reached their zenith, height became an obsession of church builders, too. Even today, the tallest buildings in Lincoln, Norwich and York, for example, are their medieval cathedrals. From 1311 until 1549 when its spire collapsed in a storm, Lincoln Cathedral was the world’s tallest building. In England, Salisbury Cathedral soars 404ft into the Wiltshire sky, a fact – albeit measured in metres – well known to a pair of Russian Novichok-loving church spotters on a fateful daytrip to the city five years ago.

Shortly after the completion of the Salisbury spire, the campanile of Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico rose high above the city’s Piazza del Campo. The grand palazzi encircling the square at uniform height belonged to the city’s most powerful families. They had agreed to climb down from their rival towers to live in tokenistic harmony with one another under the jurisdiction of their city council that now, significantly, commanded the architectural heights. It was an important moment in civic and architectural history. Civic buildings rose high. But not for long.

For 85 years, Manchester’s neo-Gothic Town Hall, designed by Alfred Waterhouse and completed in 1877, had been the city’s tallest building, its tower climbing to 285ft. In 1962, its crown was usurped by the CIS (Co-operative Insurance) Tower, a 387ft glass and steel commercial tower by Gordon Tait and G S Hay. The new look for Sixties Manchester was Fifties Manhattan. And significantly so. It was Manhattan that reshaped our idea of what city centres might be. Here commerce had triumphed, expressing itself in a skyline that made those of other cities around the world look like scale models.

While making a BBC radio documentary in 2000 on New York and Chicago – in another programme we looked at Liverpool and Manchester – my producer Jane Beresford sought out audio archive from the Ellis Island Museum. What did transatlantic immigrants, the best part of a century earlier, first experience when their ships arrived in New York perilously close to the First World War? We listened rapt as one young Irishman recalled hearing the cry “Land-ahoy!” and, rushing to the side of his ship, seeing not the Statue of Liberty with her promise to take in “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” but, rising from the horizon, first the crown and then the Gothic shaft of the brand new, 792ft high Woolworth Building, the tallest in the world. Now, America – synonymous with New York to our thrilled 18-year-old – was talking. Here was the opportunity to breathe free and to walk very tall indeed.

With its steel frame clad in limestone and terracotta and adorned with Gothic gargoyles, turrets and pinnacles, the Woolworth Building – commissioned by Frank Winfield Woolworth, the self-made 5c and 10c store magnate and designed by Cass Gilbert – was dubbed the “Cathedral of Commerce”. From pavement to pinnacle it was filled with offices to rent. Architecturally it dominated ecclesiastical and civic buildings alike. From then on, the race was as high into the sky as commercial risk dared and bylaws allowed. The Chrysler Building, 1930. An elegant 1,046ft Art Deco spire of offices. Speculative development designed by William Van Alen for Walter Chrysler. World’s tallest building for eleven months before the completion of the 1,250ft Empire State Building. Speculative. Offices. A hollow mast added on top made the dizzying skyscraper even taller. Crazy promise of an airship docking station at this immense and windy height over Fifth Avenue. Hit by Wall Street Crash. Known as the Empty State Building until it filled up with government agencies and related companies during the Second World War.

A success and symbol of the city ever since, the Empire State Building was rivalled in 20th century New York only perhaps by the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. Completed in 1973 and filled with office after office, the towers, designed by Minoru Yamasaki were a real estate project by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. A symbol of US-led globalisation, the World Trade Center was sold to the New York property magnate Larry Silverstein on 24 July 2001. Less than two months later I was asked to write a 2,000-word newspaper piece, “Is this the end of the skyscraper?” While there was much to ponder, my response could have been summed up in just one word: No.

What has been fascinating to witness since is not just the rude health, and largely crude form, of the 21st-century global skyscraper, but the fact that so many super tall buildings are increasingly neither civic nor commercial – in the sense of offices – but residential. For all the momentary fear of psychotics flying hijacked airliners into tall buildings, those who can afford to do so, appear to revel in living ever further above city streets. One bizarre fashion – New York again – has been for super-tall, super-skinny skyscrapers with as few apartments per floor as possible, perhaps even an entire floor of a skyscraper to yourself, a snip for today’s luxury, hot-tub lifestyle celebrity VIP at just 10 or 30 million dollars a pop.

When I first encountered one of these provocations – 432 Park Avenue, 1,396ft high, architect Rafael Vigñoly, completed 2015 – I shared Dante’s experience of looking up at the Girasenda Tower. Fleeting clouds gave the impression that the pencil-thin tower was leaning, swaying even. Later, I read that 432 Park Lane groaned and creaked, leaked and suffered from electrical problems and stuck elevators. As a gift to the media, Vigñoly said the design of the tower’s gridded structure was based on what US newspapers referred to as a “trash can” designed in 1906 by the Viennese architect Josef Hoffmann. While Hoffmann’s wastepaper basket is elegant, few people, especially those who have forked out a fortune for a luxury Park Avenue apartment, wish for their home to be likened to a “trash can”.

I can only imagine what life is like in a skinny skyscraper. I have witnessed water swishing from side to side in a lavatory basin in a Chicago tower in stormy weather – the owner of the apartment said her cats liked playing with it – and even, in squally weather, my dry martini was involuntarily shaken, if not stirred, without the help of a bartender in the now-closed bar on the 96th floor of Chicago’s Darth Vader-like John Hancock Center.

The world’s tallest purely residential tower, at 1,550ft, is currently Manhattan’s Central Park Tower. Others, though, whether rising from Dubai or elsewhere in the Middle and Far East – and perhaps India and Russia – will catch up or overtake soon enough. Height aside, their designs tend to be bland or wilful. If, like the towers of Bologna and San Gimignano they disappeared through the effects of storms, earthquakes or wars, would we want to rebuild them?

The very day in July 1902 that the bell tower of St Mark’s collapsed, with the loss of a solitary cat’s life, the city of Venice declared it would be rebuilt brick-by-brick. Venice without its tallest and grandest campanile, first completed in 1514, would be all but unthinkable. In 1995, the tower was found to be leaning. A five-year programme of works completed in 2013 involved adjustable titanium cables holding the tower’s foundations in check.

As to the future of ever-higher city skyscrapers, whether raced up to serve the needs of commerce or, increasingly, ambitious homeowners, it is worth looking to Paris. Following the completion of the sentinel-like and hugely controversial 689ft Tour Montparnasse in 1973, a 121ft height restriction – essentially 12 floors – was imposed on new buildings in the city centre. Overruled by Mayor Bernard Delanoë in 2010, a new limit of 180m (590ft) was set, almost every last metre of which will be consumed by the up-and-coming La Tour Triangle, a brash, cartoon-like tower designed by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron in the 15th arrondissement stuffed with offices, a “luxury hotel”, shops, a conference centre, a cultural centre, le-blah-di-blah, for the edification and profit of the people of Paris. To stop further buildings like this, the 37m height limit has been reimposed across central Paris.

To the immediate west of the city centre, the dedicated commercial district La Défense is awash with Alphaville skyscrapers, a quartier to experiment in architecturally without further damage to what is at heart a low-lying city. Rightly, Bologna will restore its wayward medieval tower, yet whether we really wish our cities to be crowded with ever more, ever higher towers, most of them residential or commercial and about as civic-minded as an earthquake, remains a question we might yet wish to face up to as Dante did seven hundred years ago.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments